The Biggest Landslides In US Presidential Elections

Presidential elections can be some of the most contentious times in American politics. Campaigns can become nasty and personal, as candidates mercilessly attack each other for their positions and perceived weaknesses. It seems, sometimes, like every election cycle just brings more vitriol and less substance. Even televised debates, a staple since the Jimmy Carter era, are now in jeopardy of happening at all.

Presidents are officially elected via the Electoral College, a process that is laid out in Article II of the Constitution. Though the process has changed over the last 250 years, the Electoral College system has still stayed intact. While most recent presidential elections have been relatively close in terms of Electoral College votes, in the past, there have been some pretty one-sided contests. Some of the founding fathers of the nation also hold the distinction of having some of the largest blowout victories in Electoral College history. Get ready — these are the biggest landslides in U.S. presidential elections.

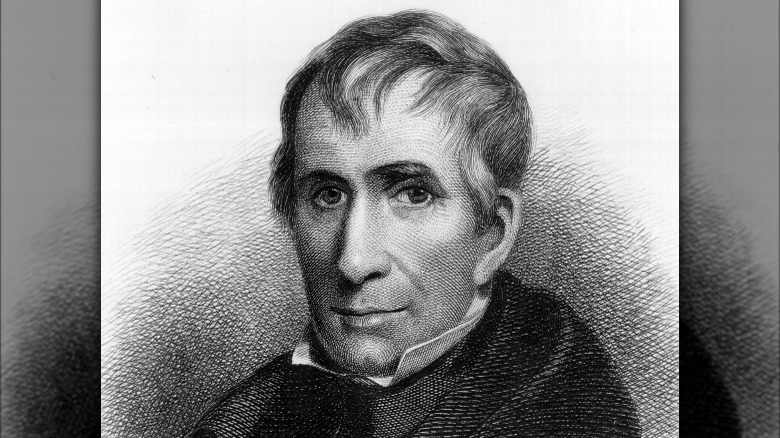

William Henry Harrison beats incumbent Martin Van Buren

In 1840, the United States was at a crossroads economically. The country was just coming out of the financial Panic of 1837, which was characterized by high inflation, high unemployment, and high rates of private business failure. According to the UVA's Miller Center, this resulted in the incumbent president, Democrat Martin Van Buren, becoming increasingly unpopular among voters. The main political rivals of the Democrats in the mid-19th century were the Whig party, led by Senators Daniel Webster and Henry Clay. Seeing Van Buren as vulnerable, they chose as their candidate William Henry Harrison, a veteran and hero of the War of 1812, and his running mate was John Tyler.

The main issues of the election were the country's economic problems and the contrast of lifestyles between Harrison and Van Buren. According to the National Parks Service, it was the first presidential election where candidates actively campaigned for themselves, and the Harrison and the Whig party painted Van Buren as economically irresponsible. They accused him of living a lavish and wealthy lifestyle while the country was in financial crisis. In contrast, the Whigs touted Harrison's extensive war record — like his famous victories at the Tippecanoe River — and portrayed him as a "log cabin" type of person and man of the people.

The results showed the country was significantly in favor of the war veteran Harrison, who won with a huge victory of 234-60 in the Electoral College (per UC Santa Barbara).

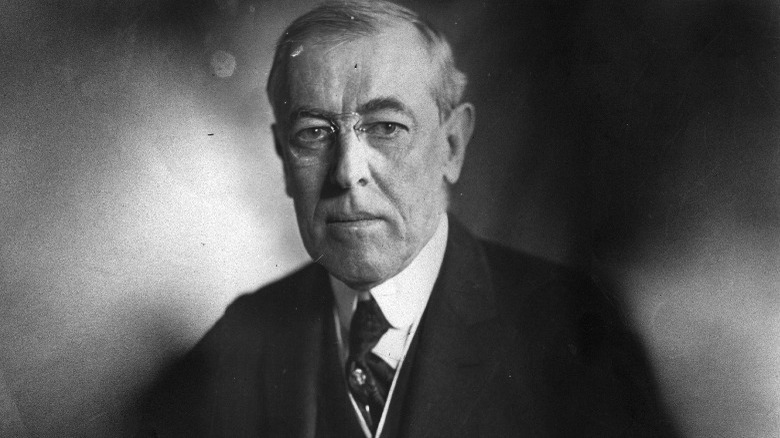

Woodrow Wilson beats the divided Republicans

The presidential election of 1912 featured three distinct candidates, with New Jersey Governor Woodrow Wilson, Theodore Roosevelt, and the incumbent President William Howard Taft all competing to win. According to Rutgers University, Roosevelt had previously been president for two terms from 1901-1909, but at the time, the 22nd Amendment was not in place, so he was free to run again in 1912. He was succeeded by William Howard Taft in 1909, who Roosevelt had practically hand-picked as his successor, but by 1912, they were having deep disagreements.

Roosevelt's main points of contention were Taft's judicial, economic, and conservationist policies, and he decided to challenge Taft for his second term. Both Roosevelt and Taft were members of the Republican Party, but after the party leaders chose Taft for the nomination — in obvious defiance of the voters' will — Roosevelt and his supporters left the Republican convention and decided to form their own party. This became known as the Progressive Party.

The voters of the Republican Party were split, with some supporting the Progressive Roosevelt and some still supporting Republican Taft. This made the pickings easy for the Democratic challenger Wilson, who coasted to victory with a stunning 435 Electoral College votes to Roosevelt's 88 and Taft's lowly 8 (via UC Santa Barbara). The New York Times referred to it as a "disastrous defeat" and "the downfall of the Republican Party."

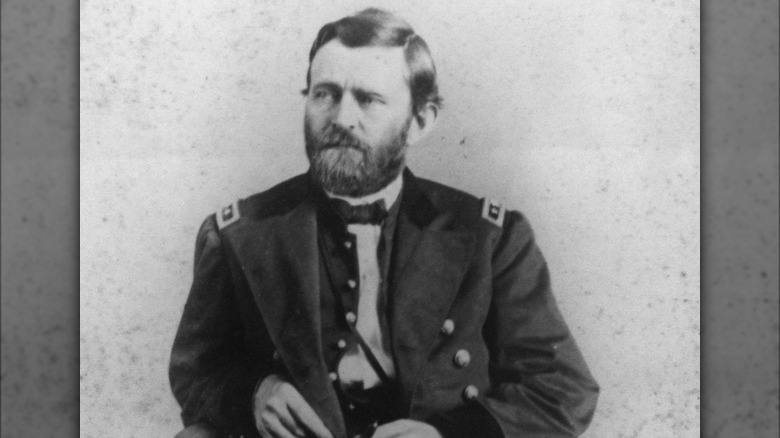

Ulysses S. Grant beats a dead man

The 1872 Presidential election, held at the height of the Reconstruction Era, featured incumbent Republican Ulysses S. Grant facing off against Democrat Horace Greeley. Grant had originally won the presidency in 1868, using his popular image as the leading Union general of the Civil War (per the UVA's Miller Center). He destroyed his opponent, New York Gov. Horatio Seymour, by a nearly 3:1 margin in the Electoral College. Four years later, Grant was still popular, but part of the Republican Party was upset with him over his Reconstruction policies, and they broke off and formed the Liberal Republican Party. They nominated as their candidate Horace Greeley, a famous newspaper editor and founder of the New York Tribune.

The Democrats, without a suitable candidate themselves, also nominated Greeley as their choice, and he went into Election Day as the top option for both the Democrats and Liberal Republicans. However, his constant flip-flopping on issues and inconsistent policies ultimately led to his downfall, and Grant easily skated to an overwhelming victory, winning over 81% of the Electoral College. In even worse news, just three weeks after the general election and before the Electoral College had officially met, Greeley died of natural causes (via UC Santa Barbara). Grant had won 286 Electoral College votes, and Greeley's 66 votes were split among several living individuals. Republicans had a great showing elsewhere in the election, which The New York Times referred to as a "tidal wave."

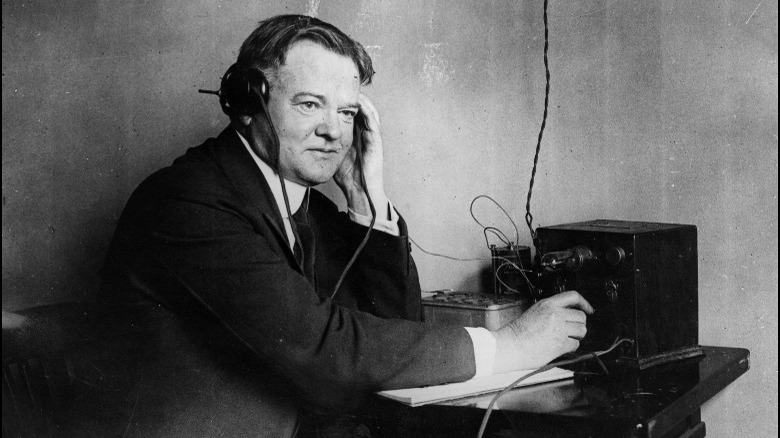

Herbert Hoover destroys his Catholic opponent of prohibition

In 1928, at the height of Prohibition and at the tail end of the "roaring '20s," Republican Herbert Hoover faced off against Democrat Alfred Smith for the presidency. Incumbent Calvin Coolidge had taken over the presidency in 1923 — when he was the vice president and Warren G. Harding died — and though he won the 1924 election, he chose not to run again in 1928 (per The White House). The Republicans nominated Hoover on the first ballot because he enjoyed the strong support of their most important constituents, and he received the endorsement of Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon, who controlled all of Pennsylvania's electoral delegates (via UVA's Miller Center).

The Democrats nominated Smith, a Catholic and strong opponent of Prohibition, on their first ballot, too. Per UVA's Miller Center, they tried to balance Smith's potentially fatal Catholicism and stance on prohibition with a running mate, Senator Joseph G. Robinson, who called himself a "Protestant Prohibitionist." Hoover had come out as promising robust enforcement of Prohibition, and Democrats felt the need to emphasize their adherence to the laws — even though their main nominee was publicly against them. The Ku Klux Klan (KKK) supported Hoover during the election, and they publicly castigated Smith for his religion on several occasions.

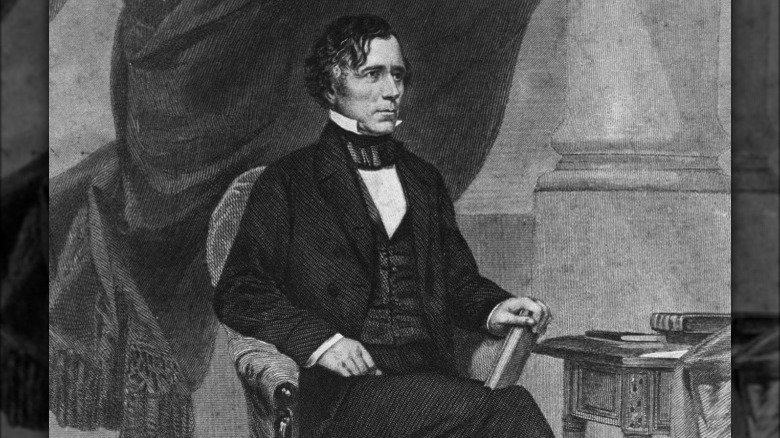

Franklin Pierce wins a personality contest

In 1852, both the Democratic and Whig parties had difficulties selecting suitable candidates for the upcoming presidential election. According to the UVA's Miller Center, the incumbent president, Whig Millard Fillmore, lost his party's nomination over his previous support for the controversial Compromise of 1850. It took 53 ballots, but finally, Gen. Winfield Scott, veteran of the recent Mexican-American War, won the nomination. The Democrats' problem was that none of their leading candidates could get over the two-thirds threshold to secure the nomination, and soon their ballots started to pile up, too. Finally, a dark horse emerged in the form of the relatively unknown Franklin Pierce, a veteran of the Mexican-American War himself who secured the nomination after 48 ballots. Pierce, being both pro-slavery and a northerner, was able to appease enough factions of the party to get broad support.

The biggest issue of the day was slavery, but neither party was eager to talk about it in their campaign platforms or speeches because of how controversial and divisive it was at the time — just a decade before the Civil War would start. The election turned into a personality contest between Scott and Pierce, with both sides trying to downplay the other's military service and portray the other as a coward. Scott's rhetoric and controversial views on slavery within the Whigs sealed his fate, and Pierce easily coasted to victory, with 254 Electoral College votes to Scott's lowly 42 (via UC Santa Barbara).

Dwight Eisenhower beats Adlai Stevenson twice

It's often the case in modern elections that candidates find themselves facing off against the same opponents year after year, but that's not often the case for presidential elections. Yet, in both the 1952 and 1956 elections, Dwight "Ike" Eisenhower took on challenger Adlai Stevenson II (per the UVA's Miller Center).

In the 1952 election, Eisenhower campaigned on his famous military record, which included a legendary record in World War II and a stint as the commander of NATO forces in Europe after the war. Initially reluctant to enter politics, Eisenhower finally announced his candidacy in January 1952 and received widespread support among Republicans. The Democrats chose Stevenson, who was the popular Governor of Illinois. Stevenson also had a war record from serving in the Navy, but he was no match for Eisenhower, who destroyed him with 442 Electoral College votes to his 89. Eisenhower even captured much of the south, which was thought to be a Democrat stronghold.

In 1956, Stevenson again won the nomination and took on Eisenhower a second time. Ike almost decided not to run after suffering a heart attack in late 1955, but he pulled through and decided to run the following February (via the National Parks Service). Stevenson tried to attack Eisenhower as ineffective, but he maintained strong support throughout the electorate, including during the tense Suez Crisis on the eve of the election. He won again in a landslide, with 457 votes to Stevenson's 73 (via UC Santa Barbara).

LBJ beats Barry Goldwater with the Daisy Girl commercial

In late 1964, as the Vietnam War was beginning to boil and the country was still mourning the death of President John Kennedy, its citizens sat down and prepared for another election. President Lyndon B. Johnson had taken over the job the previous November after the assassination of Kennedy, and in the year since, he had several legislative successes and enjoyed almost universally high approval ratings (via UVA's Miller Center). His foe in the race was Republican Senator Barry Goldwater of Arizona, who campaigned on bringing the party back toward hardline conservatism. However, while Johnson was popular and much exalted among the Democrat party and the larger American public, Goldwater's fierce conservatism alienated large numbers of voters, including four-fifths of his own party, who were more moderate. The campaign issues revolved mainly around the burgeoning Vietnam War and policies regarding nuclear weapons.

According to the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Goldwater had suggested using "low-yield" tactical nuclear weapons in Vietnam as a way to disrupt Viet Cong supply lines and defoliate forests. Johnson capitalized on this remark — which terrified much of the country — by creating and airing the famous "Daisy Girl" commercial. The video depicted the ominous conclusions of a world with unrestrained nuclear weapons and convinced much of the electorate that Goldwater was unfit for the job. The result: Johnson bowled over Goldwater in a landslide, winning 486 Electoral College votes to Goldwater's 52 (via UC Santa Barbara).

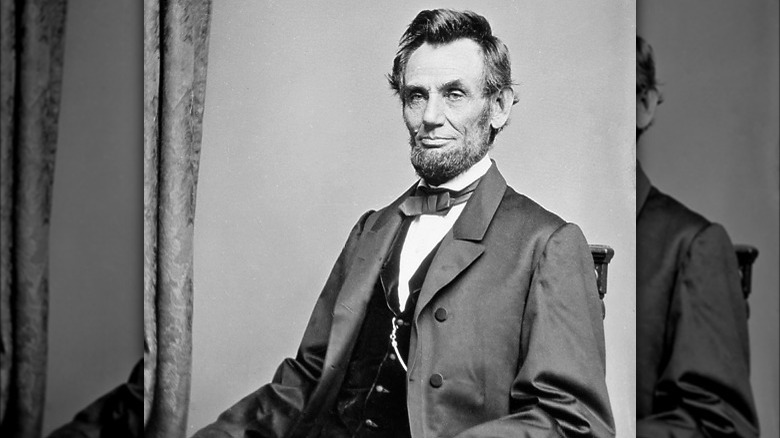

Abraham Lincoln defeats his former general

At the height of the bloody American Civil War, in late 1864, President Abraham Lincoln came up for reelection. Though the Union would go on to defeat the Confederacy the following year at Appomattox Court House, in November '64, his reelection was anything but a certainty. The Union Army had been fighting the war since 1861, and casualties were quickly mounting with no end in sight (via History).

Former head of the Union Army Gen. George B. McClellan, challenged Lincoln for the presidency. Lincoln had dismissed McClellan from command in late 1862 amid his constant timidity in the face of battle, and McClellan sought his revenge at the ballot box. He tried to portray Lincoln as a poor leader and commander in chief, criticizing him for "four years of failure" and repudiating the Emancipation Proclamation (via the University of Houston).

Lincoln had run on the Republican ticket in 1860 with Hannibal Hamlin, but in 1864, he was a part of the National Union Party (NUP), and he changed his vice president to former Democratic Senator Andrew Johnson. The NUP was a conglomeration of part of both the Republican and Democratic parties, which had partly split at the time over the issue of continuing the war and freeing enslaved African Americans. Though Lincoln was worried about the election being close, he trounced McClellan in the Electoral College by a margin of 212-21 (via UC Santa Barbara).

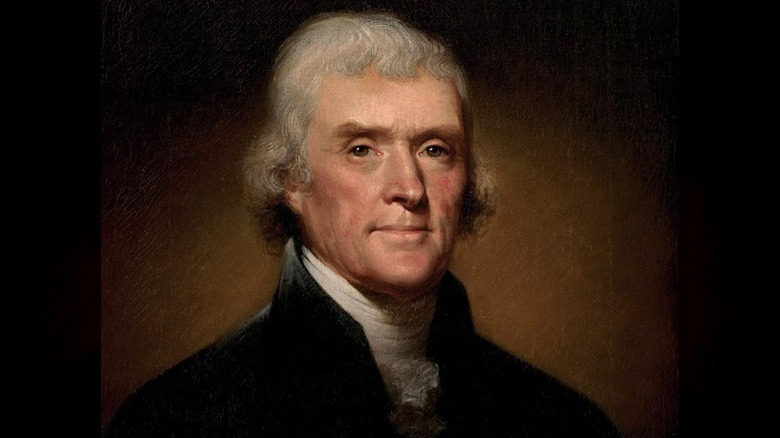

Thomas Jefferson finally wins the electoral college in a landslide

In 1804, Thomas Jefferson, though president since 1801, was still seeking his first victory in the Electoral College. He lost his first run in 1796 to John Adams, and though he defeated Aaron Burr for the presidency in 1800, they tied in the Electoral College, and he won by a vote in the House of Representatives (via UVA's Miller Center). Finally, 1804 looked like the year Jefferson would finally win his grand victory. He was incredibly popular at the time due to the recent Louisiana Purchase, which had immense public support, and the Republicans nominated him at their inaugural caucus in February.

The Republicans' opponent at the time was the fledgling Federalist Party, who did not hold a caucus but informally backed their former Vice Presidential candidate from 1800, Charles C. Pinckney. The Federalists tried to scandalize Jefferson by "exposing" his affair with his slave, Sally Hemings, but Jefferson refused to play into their hands and stayed silent on the subject. In the election, as expected, Jefferson barely faced any competition. He finally won the Electoral College with 162 votes to Pinckney's 14 and took 14 out of 17 states (via the Library of Congress).

Richard Nixon and the silent majority reign supreme

Rightfully criticized for his atrocious behavior during the Watergate scandal, many regard Richard Nixon as one of the worst presidents in American history. Yet, it might surprise younger generations of Americans to find out that Nixon was actually once one of the most popular presidents of all time. He served as vice president during the Eisenhower Administration in the 1950s, and in 1968, after a previous defeat in 1960, he was finally elected president by a razor-thin margin of voters (via UVA's Miller Center).

His opponent in 1972 was George McGovern, a Democratic Senator representing South Dakota. McGovern struggled from the outset and failed to gain even a modicum of popularity throughout the race. After it emerged that his vice presidential candidate, Thomas Eagleton, had undergone mental health treatment, the tide turned against McGovern decisively. Nixon was popular with the American public over his recent signing of the Strategic Arms Limitation Treaty, as well as his visits to both China and the Soviet Union that year. His handling of the Vietnam War also drew praise from the electorate.

On election day, Nixon defeated McGovern by more than 18 million votes, and in the Electoral College, he received 520 votes to McGovern's pathetic 17 (via UC Santa Barbara). The popular vote margin is still the largest in American history (via Politico).

Ronald Reagan's two massive victories

In 1937, a young actor named Ronald Reagan made his debut acting in a film called "Love is on the Air." Over the next 30 years, Reagan starred in dozens more films and television programs, endearing himself to the American public as one of the finest actors in Hollywood (via the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library). After finishing his acting career, Reagan turned to politics, first as governor of California and eventually as president of the United States in 1980.

In 1980, Reagan took on incumbent Jimmy Carter, but the Iranian hostage crisis and subsequent failed rescue mission tanked any chance that Carter had for reelection (via the Brookings Institution). Reagan walked to victory, destroying Carter by a margin of 489-49 in the Electoral College. The New York Times called the victory "startling" but predicted "we will have a one-term President" because of Reagan's age. They could not have been more wrong.

Four years later, in 1984, Reagan somehow managed to increase his already substantial margin of victory, receiving 525 Electoral College votes to Walter Mondale's 13 (via UC Santa Barbara). Mondale won only one state, Minnesota, and the District of Columbia. The popular vote wasn't any closer, with Reagan gathering nearly 17 million more.

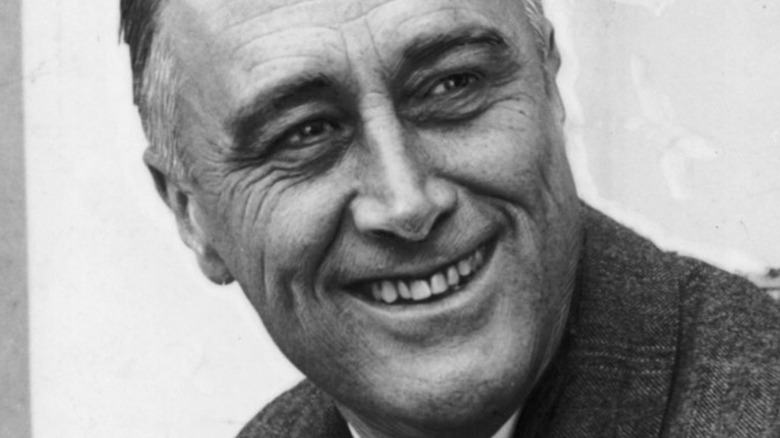

FDR's four incredible victories

Some presidents can claim to have won blowout elections, but a rare few can claim to have done that more than once. Then there's Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who managed to pull off the feat four times, a record that literally can never be broken. Roosevelt first won the presidency in 1932 after defeating Herbert Hoover (via the Roosevelt House). The country was struggling amidst the Great Depression at the time, and that, combined with Hoover's complete ineffectiveness, allowed Roosevelt to cruise to victory with nearly 90% of the Electoral College vote (via UC Santa Barbara). Four years later, in 1936, Roosevelt's victory was even greater, winning 523 votes and 98.5% of the Electoral College (via UC Santa Barbara).

In 1940, with the world at war and the United States drawing ever closer to entering, Roosevelt faced his toughest challenger yet in industrialist Wendell Willkie. Willkie criticized the New Deal and accused Roosevelt of secretly trying to get the U.S. involved in WWII (per the Roosevelt Presidential Library). Yet, Willkie proved no match, losing by over 84% of the Electoral College.

In 1944, with the country deeply involved in the fighting in Europe and the Pacific, Roosevelt ran for an unprecedented fourth term. He again coasted to victory, winning 432 Electoral College votes to his opponent's 99 (via the Miller Center). Partly in response, shortly after Roosevelt's death during his fourth term, Congress passed the 22nd Amendment, which prohibits presidents from taking office more than twice.

James Monroe and the faithless elector

In 1816, James Monroe first took over the presidency after defeating Rufus King (via UC Santa Barbara). Monroe's victory was substantial, winning the Electoral College by a margin of 183-34 and taking all but four states. Four years later, Monroe was up for reelection, and it seemed as though his unanimous victory was all but assured (per UVA's Miller Center). His policies were immensely popular throughout the country, and he had huge support within his party. In fact, his party was so confident that he was going to be renominated and reelected that most of them did not even bother to attend the Democratic-Republican (it was one party at the time) caucus in April.

The Democratic-Republicans' opponents, the Federalist Party, were almost completely broken up by this point, and they did not hold any sort of caucus or nomination process. They did not even bother to pick a candidate to endorse; they were so demoralized and sure of a Monroe victory. Monroe did not disappoint, winning every single state in what should have been a unanimous Electoral College victory. However, one single elector decided to buck his party's wishes and instead voted for John Quincy Adams, robbing Monroe of his unanimous victory. According to the Brookings Institution, technically, the Constitution does not force electors to vote for the candidate of their party, and one elector took advantage in 1820 because he did not like Monroe's administration (via Lynn W. Turner).

George Washington's two unanimous victories

George Washington is considered by many to be one of the greatest statesmen in history. The leading general of the Revolutionary War, Washington's stature in the United States is basically unrivaled. It serves to fit, then, that Washington won the first two presidential elections by unanimous vote. According to the UVA's Miller Center, the main political issue during Washington's first election in 1788 was over support for the Constitution. Federalists, like Washington, vigorously supported the Constitution as it was written and pushed for ratification. Their opponents, who called themselves the anti-Federalists, did not want the Constitution ratified as it was and wanted several amendments added to it.

However, both parties agreed on one man to lead the country: Washington. At the time, the voting system was different for the president than it is today. States were free to pick their electors however they wanted, with some opting to hold a popular vote and others opting for the state legislatures to choose. In addition, electors each had two votes, and the two candidates with the most votes became the president and vice president (via the Virginia Museum of History & Culture). In both the 1789 and 1792 elections, each elector cast one of their votes for Washington, making him a unanimous selection both years. These are the only unanimous Electoral College victories in American history.