Who Was The Real General Tso?

General Tso is a name that most Americans will know from Chinese restaurants. In 2015, NBC News proclaimed General Tso's Chicken to be the No. 1 most popular Chinese takeout dish in the U.S., and the 4th most popular overall, according to GrubHub. Fewer people will be familiar with who exactly General Tso was, or the role he played in the final century of the Qing Dynasty. The dish of sticky sweet chicken nuggets may be wildly popular in the 21st century but, as Smithsonian Magazine notes, the man it was named for certainly never ate it himself.

The real General Tso was a Chinese Imperial official named Tso Tsun-tang (左宗棠), which is now usually anglicized as Zuo Zongtang. As Britannica explains, he was a key figure in the Chinese military of the 19th century, who made his name fighting back against several rebellions which threatened the declining Qing Dynasty. History tells how the Qing Dynasty began in 1644, a Manchu dynasty, and the second time China was ruled by anyone other than the Han people. While it began as an era of prosperity for China, the end of the Qing Dynasty was full of myriad troubles. China struggled with weak leadership, poorly thought out conservative values, European colonialism, and numerous major conflicts, including civil unrest and the Opium Wars.

It was in this fraught chapter of Chinese history that Zuo Zongtang was born. He went on to live through some of the 19th century's most tumultuous times.

Zuo Zongtang

Zuo Zongtang was born in Hunan Province, a mountainous region in Southern China, and coincidentally the same province where communist leader Chairman Mao Zedong would later be born. Hunan, as the Washington Post notes, is a place that enjoys fiery foods, with more of a slow spicy burn than the sharp punch of the better-known Szechuan cuisine. The food of Hunan, with heat slowly building up over time before reaching scorching levels, is quite an apt analogy for how Zuo's career ended up going. He too, took time to rise to prominence, but, eventually, he would turn out to be a skilled soldier and a blisteringly gifted leader. Some historians have favorably compared his military ability with General Sherman, famous for fighting for the Union in the American Civil War, half a planet away in the same century.

Mental Floss explains that Zuo's family were landowners, wealthy enough to fund an extensive education, which, he hoped, would launch a political career. After passing his preliminary examinations for the civil service, Zuo Zongtang ended up largely devoting himself to agricultural and geographical studies. His career in the military, however, had a slow start. He remained largely unnoticed until 1850, when the Taiping Rebellion broke out. At the time, Zuo was already 38. Part of the reason was that, for a long time, Zuo didn't believe he'd ever achieve anything noteworthy. While his position in society gave him access to education, he evidently had a rough time as a student.

Zuo's failed examinations

Any student will be able to sympathize with Zuo Zongtang's difficulties in formal examinations. In fact, as China Daily mentions, he repeatedly failed his exams to become an official at the Chinese court. Unable to pass the needed exams, for a long time, he gave up on his aspirations to become a statesman, returning instead to Hunan to live a simple life farming, drinking tea, and reading. His reading, however, included learning all about Western sciences and political economics. It was the extensive knowledge he built up that would eventually get him noticed by local officials in need of an advisor.

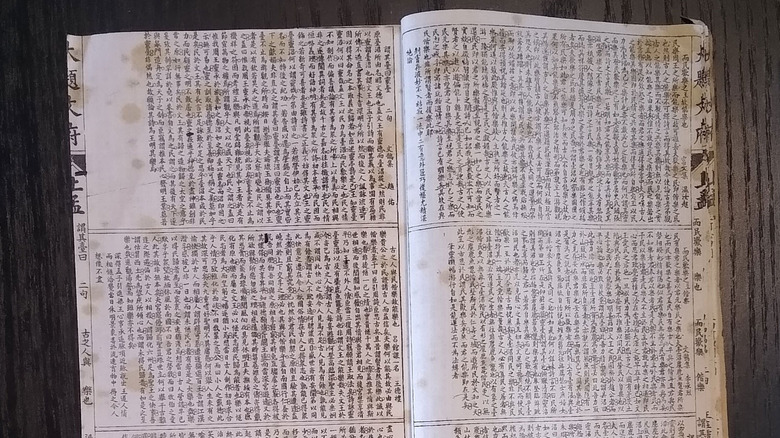

Zuo never did gain the qualifications that he once worked for. China Knowledge explains that the title of Jinshi (進士), meaning "presented scholar," was a prerequisite for public service jobs in Imperial China. Because so many Jinshi graduates became powerful political figures, it became widely recognized as a degree for generals and counselors. Members of the nobility were expected to attain one if they wanted to be treated with full esteem, and were considered lesser if they failed to earn the title. However, as a page from the College of Wooster notes, despite his distinguished career, Zuo Zongtang was never awarded a Jinshi degree. There's something quite inspiring about the fact that he succeeded anyway, and is still known as one of China's greatest imperial commanders despite missing what, for most, was considered an essential first step.

The Taiping Rebellion

The Taiping Rebellion was one of the most brutal conflicts in Chinese history: a civil war that lasted 14 years, ultimately claiming millions of lives. As the Washington Post describes, this was when Zuo Zongtang made his name, helping to save the Qing Dynasty itself.

The rebellion came about as a result of Western influence, and the rebels themselves were strong advocates of Christian doctrine. Their leader, a man named Hong Xiuquan (洪秀全), believed himself to be the brother of Jesus and was hailed as a religious prophet. He declared himself the head of a new dynasty, the Taiping Tianguo, meaning "Heavenly Kingdom of Great Peace." This name would become somewhat ironic. As well as facilitating a decade and a half of violence, Hong was a stern leader. As History explains, he insisted that his followers avoid "the cast of amorous glances, the harboring of lustful thoughts about others, the smoking of opium, and the singing of libidinous songs," and threatened those who didn't obey with decapitation.

It was Zuo Zongtang's leadership that helped secure victory for the Qing Dynasty, decisively defeating the rebels in four provinces. Despite being a Chinese civil war, the Taiping Rebellion was a direct result of growing British Influence in East Asia. After the First Opium War, the Qing Dynasty signed the Treaty of Nanjing, forcing China to make many concessions to the British, allowing Christian missionaries to enter, and introducing Hong Xiuquan to the ideas which nearly destroyed an empire.

Revolts and uprisings

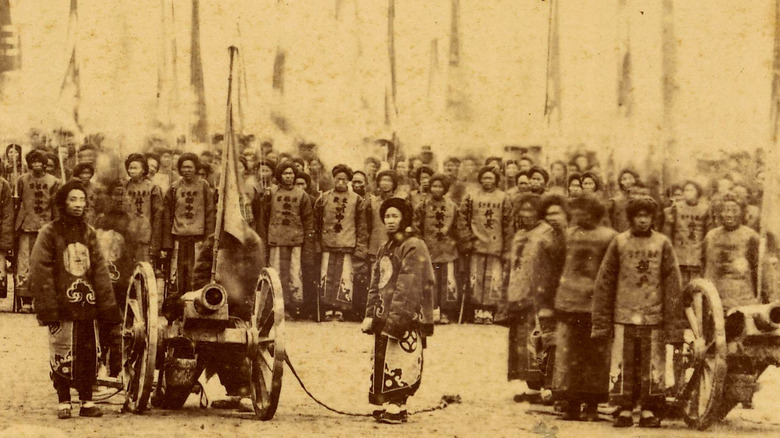

After quelling the Taiping Rebellion, Zuo Zongtang's reputation was cemented as one of the Qing Dynasty's greatest military commanders. As Britannica explains, this led to him becoming governor-general of Zhejiang and Fujian provinces in 1863, making him one of the most powerful figures in all of China. Later, in 1867, he became governor-general of Shangxi and Gansu in Northern China, to deal with another rebellion. Where the earlier uprising was Christian, these rebels were Muslim. Slowly, methodically, Zuo dismantled this rebellion using the two things he'd spent much of his life studying – economics and Western technology. Two of the most powerful tools in his arsenal weren't military might, but effective taxation and encouraging the local economy.

Zuo's success against the Muslim rebels, known as the Nian Revolt, was thanks to a doctrine he'd devised himself during the earlier Taiping Rebellion. A paper in the journal Small Wars & Insurgencies explains how Zuo became an expert at efficiently dealing with rebel forces, spurred by the fact that, in the 19th century, China was surrounded by enemies on all sides. In such a precarious situation, the Qing Dynasty needed strength in order to survive. Using the skills he'd learned during the Taiping rebellion, Zuo managed to suppress the Nian revolt, as well as another uprising, the Sufi Revolt in Central Asia. His military prowess even convinced the Russian Empire to cede the territories they were occupying in Central Asia, helping to maintain the integrity of the beleaguered Qing Dynasty.

Reconquering Xianjing

Emboldened by his successes, Zuo Zongtang was largely responsible for China annexing the Xinjiang region. Also known to the Chinese as Xiyu, Xinjiang is a large territory in the northwest of China with a fraught history. It's home to many things including fragrant fresh fruits, ruggedly beautiful mountainous landscapes, and the indigenous Uygur people who continue to be violently oppressed by the Chinese government in the 21st century, as Smithsonian Magazine describes in detail.

Central Asia Program's Uygur Initiative explains how China has a long history of trying to maintain control of Xinjiang, with varying degrees of success. Generally, whenever the central Chinese government was at its strongest, it was likely to use that strength to assert control over the region. During Zuo Zongtang's time, however, this move had primarily tactical motivations. China was under considerable threat from the Russians to the north, and from the British to the southwest via India. As a working paper from the Harvard-Yenching Institute discusses, Zuo pushed strongly for the Qing Dynasty to take control of Xinjiang, for the tactical advantage it would give. With influence from his peers, Zuo was adamant that Xinjiang should be a Chinese province. When it was retaken, he strongly advocated replacing Islam with Han Chinese culture, forcing Confucian texts to be taught in place of Muslim ones. This culturally damaging philosophy, regrettably, is not unlike the one held by the Chinese government today.

A ruthlessly effective leader

Zuo Zongtang's military skill, for better and for worse, was unquestioned. The Washington Post describes him as "utterly ruthless," no doubt out of necessity in times of such constant unrest. His self-devised counter-insurgency doctrine was key to maintaining the Qing Dynasty's power in East Asia during the 19th century, as described by a paper in Small Wars & Insurgencies. Without his influence, the doomed Qing Dynasty would likely have met its end much sooner than its eventual fall in 1911.

Even before he became a leader, Zuo was widely acknowledged for his influence, as "China at War: An Encyclopedia" discusses. He was a noteworthy figure even while serving as an advisor to Lo Ping-chang (駱秉章), the governor of Hunan. While Lo was officially the province's ruler, many recognized that Zuo was the one who was really in charge.

Later, as a general in the military, Zuo insisted on doing things his way, rather than following dogmas. One of his notable traits was his insistence on promoting soldiers based purely on their ability, ignoring their education. No doubt influenced by his own background, he preferred soldiers who were effective, even if they were completely illiterate, eschewing those who were qualified but ill-suited for higher ranking roles. An overbearing and dictatorial man, General Zuo never lost sight of the value of the land he was fighting for, working to repair the damage caused by war, planting cotton and building wool mills in his wake.

The opium scourge

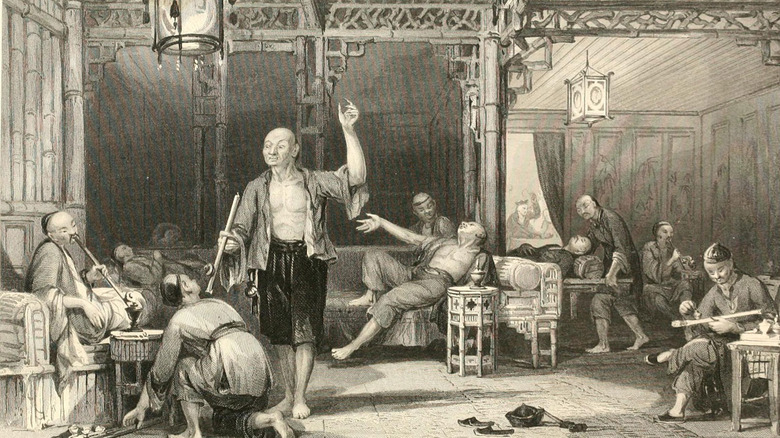

In the 19th century, China had a serious problem with opium. Britannica discusses the topic in detail, explaining that while opium had been first introduced to China around the 6th century, it had a boom in popularity around the 17th century. This was around the time tobacco smoking became popular in China after arriving via the Philippines, as South China Morning Post explains. Europeans had spread the practice of tobacco smoking all over the world and, throughout China, this also led to the widespread popularity of smoking opium. The extensive addiction which came with it was devastating to Chinese society. The Qing Dynasty's attempts to ban opium would eventually lead to the Opium Wars, as the Chinese government tried to stop the British from smuggling opium into China, a black market drug trade run by the British East India Company.

The U.S. Federal Research Division discusses how the first Opium War led to Chinese officials realizing the need to make China more resilient against outside influences. The Self-Strengthening Movement was born, and Zuo Zongtang was one of its leading champions. This led to a shift in Chinese culture, adopting more Western practices. China began teaching Western science and languages in schools, building factories and shipyards, and adopting different diplomatic practices. In the struggle against opium addiction, Zuo also applied his agricultural interests. A study in the journal Technology and Culture mentions one of his initiatives – an attempt to replace Chinese opium crops with the cultivation of cotton.

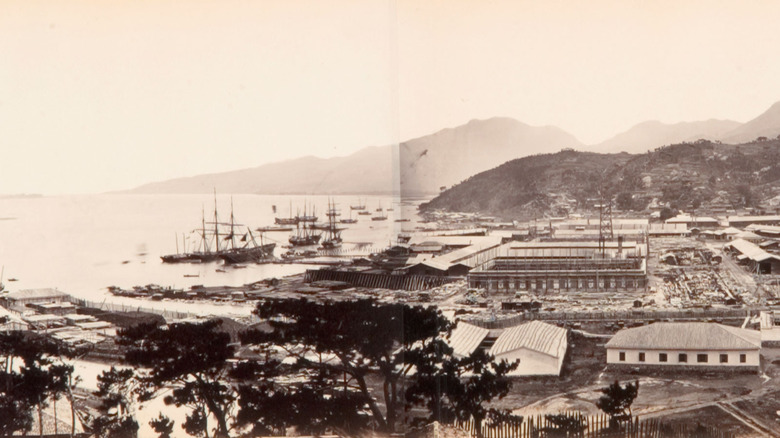

China's first modern shipyard

As part of the Self-Strengthening Movement, Zuo Zongtang made another of his great accomplishments, founding China's first modern shipyard and naval academy. While he was governor-general of the Fujiang and Zhejiang provinces, Mental Floss mentions that Zuo founded the Foochow Arsenal. Also anglicized as Fuzhou, Britannica explains that this was one of China's first large-scale experiments with Western technology. By all accounts, it was a success. Under the guidance of the French, who were occupying part of Vietnam at the time, Fuzhou became home to an expansive naval yard.

As well as a shipyard, Fuzhou Arsenal was also home to a navy school and a center for the study of Western languages and sciences. With courses offered in English and French, a generation of Chinese naval officers received Western-style training in Fuzhou, equipped with up-to-date knowledge in engineering and technical science. Unfortunately for the Qing Dynasty, as the French continued to take control of Vietnam, the peace between the two nations would become increasingly uneasy. Eventually, inevitably, conflict broke out. This marked the beginning of the Sino-French War.

The Sino-French War

In the 1880s, as France continued to move its forces northward in Vietnam, conflict drew ever nearer. China responded by deploying its own military forces in the area, and the Sino-French War began as a series of small, limited clashes. By this time, Zuo Zongtang was an old man who was, nonetheless, not allowed to retire despite being increasingly sick and blind in one eye. As Britannica notes, he was sent to South China to help defend against the French. Mental Floss further explains his extensive duties, as Commander-in-Chief, Imperial Commissioner of the Army, and Inspector General. A lot for anyone to contend with.

During the war, Zuo oversaw the ill-fated coastal defenses. The war would last from 1883 until 1885, and included the destruction of a newly built fleet of Chinese steamships, and the complete demolition of the Fuzhou Arsenal. According to "The Making of the Modern Chinese Navy," all of this happened in a matter of hours, the result of an attack by Admiral Courbet leading a fleet of French warships. With China's defenses severely mismanaged, the French navy managed to gain control of the southern Chinese coastal waters. China was forced to sue for peace with France, ceding control of Vietnam and hammering another nail into the coffin of the ailing Qing Dynasty. The Sino-French War would be the last of Zuo Zongtang's military commands. A treaty was signed between China and France in 1885, and Zuo passed away soon afterward.

General Tso's Chicken

General Tso's Chicken, the now-famous restaurant dish, was created many years later, and named in honor of General Zuo. It was first created by a chef, also from Hunan Province, by the name of Peng Chang-Kuei (彭長貴). Smithsonian Magazine explains how Peng, a renowned chef, fled mainland China in 1949 when Mao Zedong's communist party took control of the country. Taking refuge in Taiwan, Peng created the dish using classic heavy Hunanese flavors, hot and sour. A former Chinese nationalist, Peng dedicated it as a tribute to Zuo Zongtang.

Peng's original dish was vastly different from the takeout meal enjoyed today, however. The familiar sweet chicken dish was first made by a New York chef named Tsung Ting Wang (王宗廷), who visited Peng's restaurant in Taiwan while seeking out Hunanese inspiration for his own recipes. Wang's version is sweeter and with a crispier batter. Created in the USA, the dish best known today is Chinese American cuisine rather than true Chinese food, and it failed to catch on in China, being too sweet for the tastes of most Chinese restaurant-goers. That said, as NPR notes, the dish has gradually started to catch on in some parts of China, with some chefs even advertising it as a "traditional" Hunanese recipe. It may be rather different from what most people in mainland China usually enjoy for dinner, but its popularity is no doubt helped by being named after the legendary Zuo Zongtang.