Inside Sojourner Truth's Complicated Relationship With Frederick Douglass

Two of the most popular names associated with the abolitionist movement are Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass. Both were former enslaved people who became powerful figures and traveled across the U.S., speaking about the injustices of slavery, equality for all persons, and the importance of human rights.

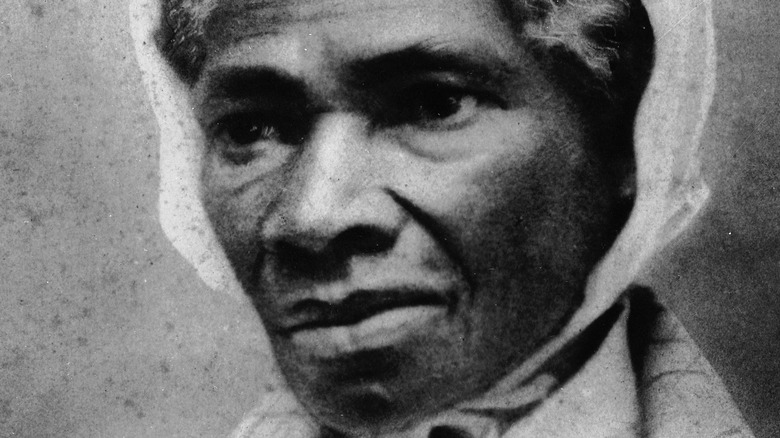

Truth, a few years older than Douglass, was born Isabella Baumfree in 1797 in New York. She was separated from her enslaved parents when she was 9 years old after being sold for $100, per History. She was a devout Christian and changed her name in 1843 after deciding to speak the truth of her faith.

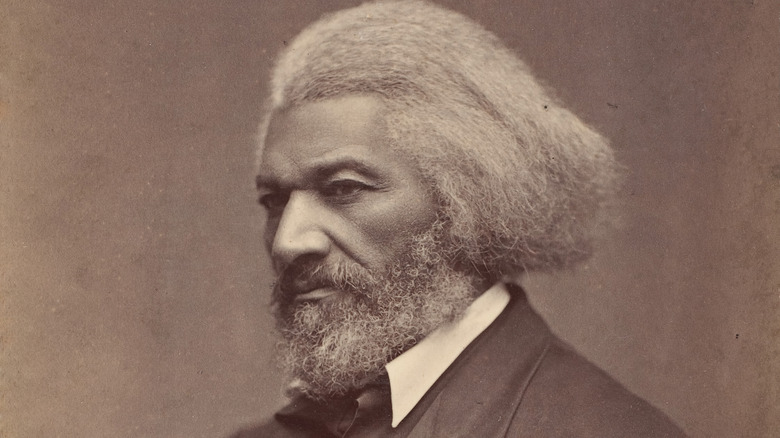

Douglass, never certain about his exact date of birth, believed he was born around 1818 in Maryland. His real name was Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, but he took the name Douglass after he escaped slavery in 1838. He never knew his mother or father and lived with his grandmother until he was sold into slavery when he was around 6 years old (via History).

Sojourner and Frederick met in Massachusetts

Sojourner Truth moved to Florence, Massachusetts, in 1843, where she lived at the Northampton Association of Education and Industry. Historic Northampton describes it as a "utopian community organized around a communally owned and operated silk mill." Members sought to change attitudes by establishing a society in which all were equal regardless of their race, sex, color, or religion. And they were unified around bringing slavery to an end.

While living there, Truth met several fellow abolitionists, and one of them happened to be Frederick Douglass, who gave several speeches there. Through the relationships she established at Northampton Association, she became more aware of matters worthy of reform, including women's rights and temperance. As a result of her time at the Northampton Association, she became well-known as a civil rights activist. The community came to an end in 1846, but its legacy lived on, per Historic Northampton.

Truth and Douglass were Garrisonian Abolitionists

During her stay at the Northampton Association of Education and Industry, Sojourner Truth also met William Lloyd Garrison (above), who developed a following of supporters known as Garrisonian abolitionists. This nonviolent group believed that all antislavery entities, including churches and the military, should be inclusive despite religious or political affiliation. They also did not become involved with any political parties, per Oxford University Press.

Truth and Frederick Douglass were affiliated with Garrisonian abolitionists, but Douglass split from the group sometime in the early 1850s because he was beginning to question whether persuasion was enough to end slavery. Around this time in 1860, Frederick planned to deliver a speech in Boston. The initial meeting was interrupted by a mob of protesters, forcing Douglass to reschedule. He delivered the speech a few days later, where he condemned the mob leaders while making a case for free speech (via Indiana University).

Truth confronted Douglass during one of his speeches

During a speech, Frederick Douglass questioned if appealing to the good nature of mankind was enough to eradicate slavery. Truth interrupted him at one point and reportedly asked, "Frederick, Is God dead?" It should be noted that there are conflicting reports of when this actually occurred, but there is little doubt that it did indeed happen. Douglass addressed the matter in his autobiography, and according to a letter from Douglass to journalist Elizabeth Wyman, the incident occurred in Salem, Ohio (per Indiana University).

Douglass wrote that Sojourner Truth interrupted him while he suggested that violence might be the only way to end slavery as the country had "sinned too long and too deeply to escape." He noted that her outburst startled him and others in the room but that he did not respond to it and carried on with his speech.

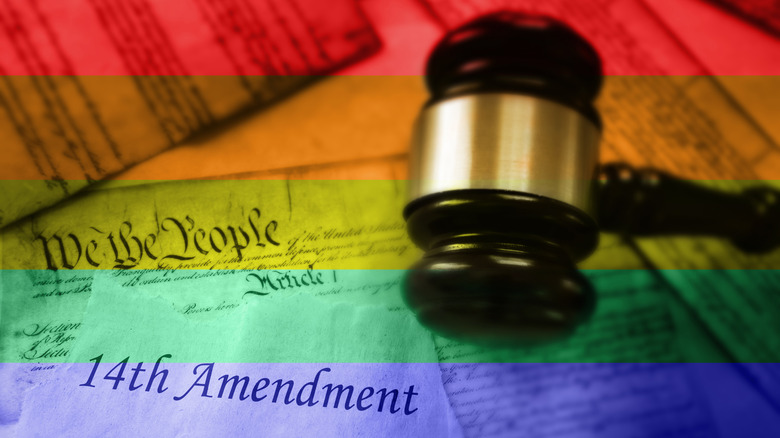

They clashed over women's rights

While Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass were fighting for the rights of Black Americans, voting was also an issue. Congress passed the Fourteenth Amendment in 1868, giving people born into slavery the same rights as free people. However, this did not include the right to vote. At this time, women did not have the right to vote, and Douglass believed that fighting for the right of Black men to vote was more significant than fighting for women's suffrage. Specifically, he believed that giving Black men the right to vote would open the door for women to vote in the future (via the National Park Service).

It should be noted that Douglass was not against the idea of women voting. In fact, he had no problem supporting the women's suffrage movement, Britannica reports. But Truth, along with women's rights advocates Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, believed that enslaved men and women should be afforded the right to vote at the same time, per Women's History.

Douglass considered Truth 'uncultured'

Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass may have been fighting for the same cause, but that does not mean that they liked everything about one another. In fact, Douglass wrote in his book, "What I Found at the Northampton Association," that the activist "seemed to feel it her duty to trip me up in my speeches and to ridicule my efforts to speak and act like a person of cultivation and refinement," adding that she was a "genuine specimen of the uncultured negro" and "cared very little for elegance of speech or refinement of manners."

That said, Douglass understood that Truth could influence people through her speeches, pointing out that she could hold an audience "spellbound." He wrote that she had a quick wit, and her arguments were "usually well directed and secured the desired results." He also wrote that she was "much respected at Florence, for she was honest, industrious, and amiable."

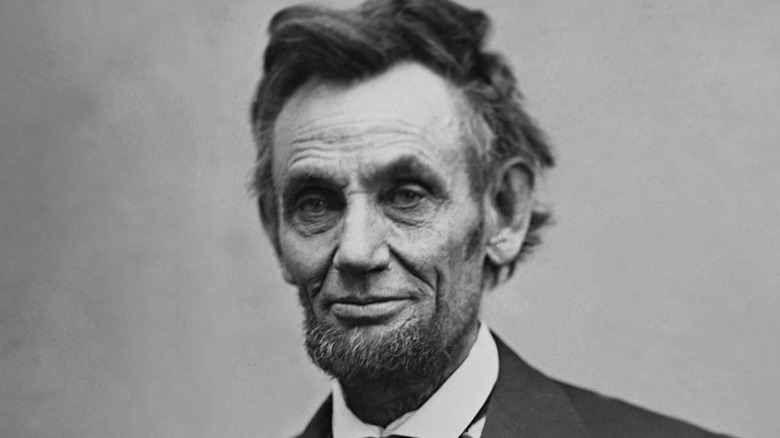

Both gained the attention of Abraham Lincoln

Sojourner Truth and Frederick Douglass were remarkable forces in the fight against slavery, and their names were known all across the country. In fact, they were so popular that they attracted the attention of President Abraham Lincoln. The Washington Informer reports that Lincoln invited Truth to the White House in 1864, where she requested that more be done for the rights of women and enslaved people alike. The meeting was perceived as one that surpassed race, gender, and socioeconomic status.

Douglass met with Lincoln two times. The first time was in 1863, when the men discussed the conditions for Black soldiers fighting in the Civil War, and the next in 1864 . While they did not see eye to eye on some issues, they had a deep respect for one another that came to light during Lincoln's second inaugural address when he told the crowd that he valued Douglass' opinion over all others (via History).