Berners Street Hoax: The Greatest Prank Of The 19th Century Explained

The U.K. capital city of London has borne witness to a long list of historically significant events all throughout its long history, from the days of the Roman empire, to the Medieval plagues killing thousands, and the London Blitz during World War II, among other examples (via Britannica). Over the course of the 2,000 years of London's existence, though, there have also been a number of lighthearted things that took place within the city limits, like large-scale public pranks dating back to the 19th century, if not earlier, according to Londonist.

In 1866, for example, hundreds of Londoners gathered, demanding entrance to the London Zoological Society, or the London Zoo, on a day that it was closed. In the instance of that prank in particular, now known as "The Procession of Animals," each person who showed up on that day had a fraudulent ticket, sold to them as an April Fool's joke (per Hoaxes). Once denied access, there was nearly a riot. The constable had to be called in to disperse the crowd.

Even before that, though, there was the so-called Berners Street hoax in 1810, perpetrated on a well-to-do Londoner at the time known only to history as Mrs. Tottenham. To this day, the Berners Street hoax is considered by many to be the greatest known hoax of the 19th century. The mischievous plot was the scheme of a man named Theodore Hook, a well-known writer in his time, though today he is largely forgotten (per Britannica).

The first person to show up on that day was a chimney sweep

It all began for Mrs. Tottenham in the early morning hours of November 27, 1810, when a chimney sweep knocked on the door of Tottenham's London address at 54 Berners Street, according to Curious Historian. That chimney sweep was there, he said, because someone at that address had requested his services. A member of Tottenham's staff answered the door, and unaware of what the chimney sweep was referring to, sent the tradesman on his way.

Soon enough, though, the long day that the Tottenham house staff were in for only worsened, as more and more chimney sweeps descended upon the address. Those chimney sweeps were followed up by a coal cart carrying a sizable load, which, according to the men who were there to deliver it, someone at 54 Berners Street had ordered, as History Today goes on to explain.

One can imagine the dismay of Mrs. Tottenham and her staff as they sent one after the other about their business, including the coal cart. As that cart disappeared, they likely imagined the unusual sequence of events they'd experienced that morning was finally over. They were wrong.

The cake makers followed

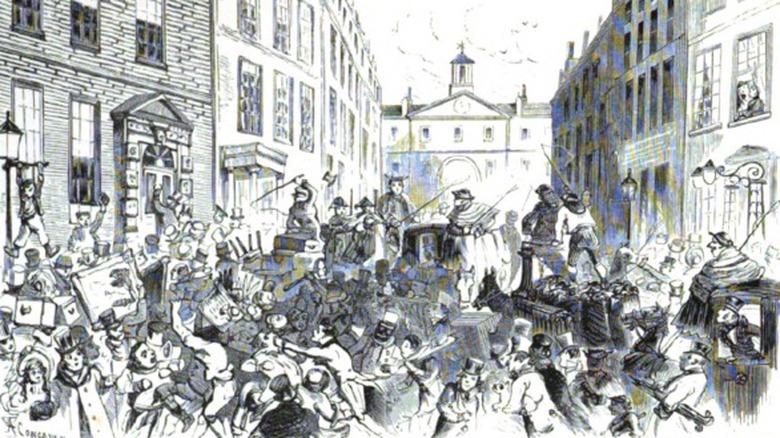

As History Today goes on to record, the chimney sweeps and the coal cart were just the first in a seemingly endless procession of deliveries to visit Berners Street on that day, including thousands of tradespeople, as well as priests and ministers. Early on in the day a cake maker arrived, soon followed by doctors and surgeons. All of them claimed that someone at the address had summoned them, but nobody in the Tottenham household knew what had happened.

There were butchers with meat, fishmongers with fish, and even the mayor of London at that time paid a visit, summoned — or so he thought — to the bedside of an ailing Mrs. Tottenham, who was in fact very much in good health, per Curious Historian. In the long list of unusual visitors to rap their knuckles on the doorway of 54 Berners Street on November 27, 1810 was a piano-maker hauling a dozen pianos, and even undertakers with coffins for poor Mrs. Tottenham, who had died — or so they had heard.

By 5 p.m., an immense crowd had gathered

Unwanted visitors and unplanned deliveries continued to call on 54 Berners Street all throughout the day. By 5 p.m., word had spread all throughout London that something very strange indeed was taking place. For this reason, onlookers gathered to see the commotion, and the street itself became impassable. Even such notable dignitaries as the archbishop of Canterbury, Charles Manners-Sutton (pictured) and the Duke of York took time out of their day to take in the spectacle. The crowds and commotion became so dense that the police were called in by the evening to break up the crowd of onlookers, according to History Today.

To this day, no one knows for sure what exactly motivated the incident that Jackson's Oxford Journal, an English 19th-century newspaper, referred to "the greatest hoax that ever has been heard of in this Metropolis," and "despicable waggery" (via Atlas Obscura). Sending someone to an address to perform some work was a common enough prank at the time, according to Curious Historian. No one in history, though, had attempted something like it at such a grand scale. And although Hook, a known prankster, never fully explained his rationale, the most commonly-accepted explanation for the well-known writer's reasoning was for no other reason than to simply settle a bet.

Hook put ads in London newspapers

Though duped tradespeople and fooled famous Londoners called for an arrest, Hook (pictured) never faced any legal ramifications for summoning such large crowds through a series of advertisements in London newspapers. He more or less fessed up to the hoax, though, in an autobiography published after his death. In a novel published in his lifetime, titled "Gilbert Gurney," a character also remarks, "What else made the effect in Berners Street? I am the man."

The wager, it's said, was whether or not Hook — who loved to show up at parties uninvited (via Atlas Obscura) and is even the first known person to ever mail a postcard to himself (per Curious Historian) — could turn any address into the most famous address in all of London. Some do say, though, that Mrs. Tottenham had somehow upset him. In truth, poor Mrs. Tottenham and her household might have been nothing more than the unlucky target of Hook's mischief. To this day, no one knows for sure.