How Miles Davis' Wife Betty Changed Funk Music Forever

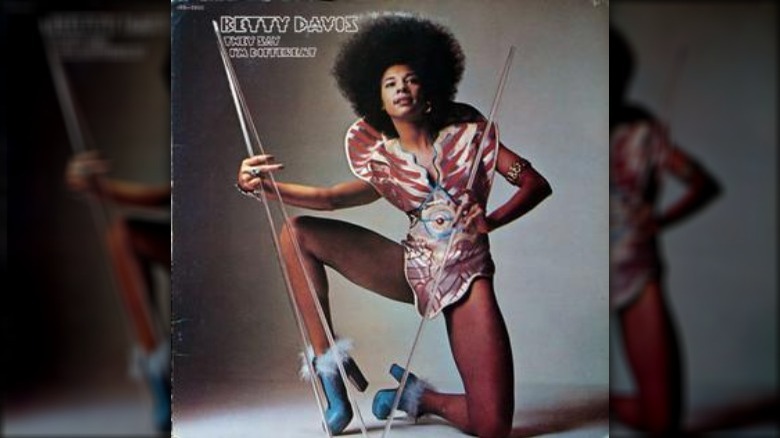

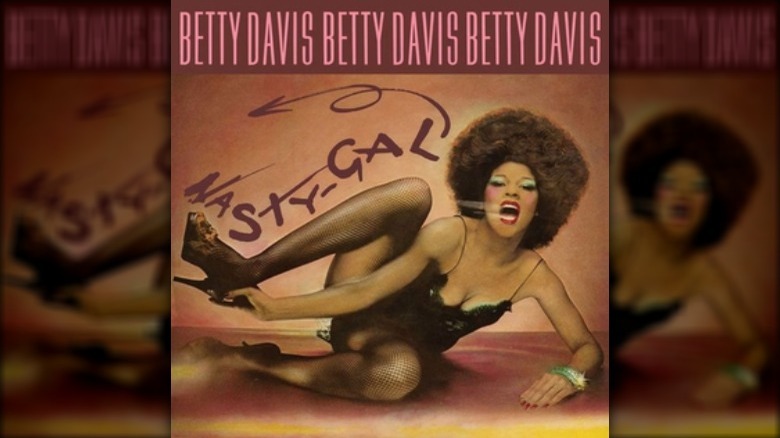

When funk pioneer Betty Davis released her second LP in 1974, she may have felt that she was finally on the way to breaking into the mainstream. However, in hindsight, the record's title, "They Say I'm Different," may be considered an omen. Davis would release just one more album in the 1970s, 1975's "Nasty Girl," before fading into obscurity. Today, it seems her provocative performances and songs were just too ahead of their time for the funk scene of the day.

But while Davis may never have received the plaudits or commercial success she deserved during her short career, as the years have passed her contribution to funk has become evident, with contemporary critics praising Davis for her originality and lasting influence on countless performers. Born Betty Mabry, the future funk icon emerged in New York in the mid-1960s as a model, having studied at the city's Fashion Institute of Technology, according to AllMusic. She released a smattering of singles under her birth name, and wrote music for the psychedelic soul group The Chambers Brothers, all the while focusing on her fledgling modelling career.

But all that was to change towards the end of the decade thanks to a life-altering meeting with one of the biggest names in 20th-century music: Miles Davis, whom Betty married in 1968. In 1989 the jazz legend wrote in his autobiography: "If Betty were singing today she'd be something like Madonna; something like Prince, only as a woman." But though Betty Davis never received the reverence she deserved, her impact on music has been vast.

Betty turned Miles Davis' career around

Betty Davis first met her future husband in a club, which is no surprise; according to numerous sources, the model was a regular in multiple fashionable New York hangouts, and a natural networker and party person. She later recalled: "I went to a dance concert, and I saw this great-looking guy in this suit. I thought he was fantastic-looking. I contacted a photographer I knew and told him about this guy. My friend said it sounded like Miles Davis. I had no idea who he was" (via The Washington Post).

According to The Guardian, Betty had an almost instantaneous impact on the jazz legend, helping him to redefine his art and aesthetic within a quickly changing musical milieu. It is argued that Davis, after nearly two decades at the vanguard of avant-garde music, was in danger of becoming irrelevant. His new partner introduced him to several new genres, including acid rock and funk, as well as the music of Jimi Hendrix, James Brown, and Sly Stone, all of whom were in the ascendency towards the end of the 1960s and who were redefining the musical landscape.

Betty used Davis' connections to start a band

Betty was just 22 when she married Miles Davis, helped to recalibrate his style — both musically and sartorially — and pushed him to pioneer the next stage of his career, characterized by African rhythms and rock-inspired jazz-fusion, culminating in his 1970 masterpiece "Bitches Brew." Even the name was Betty's idea, and while the album seemed to herald Miles' successful reinvention after the dawning of psychedelia, the artistic renaissance he enjoyed was intentional. Betty recalled, "I never took drugs. I was really into my body and I wouldn't do anything to damage myself. When I was with Miles, he was clean — he even stopped smoking. I had something to do with it, but it was his willpower" (via The Guardian).

But the marriage was not a success, and they divorced after a year. According to Miles Davis' autobiography, their time together had always been turbulent, but things ended when he was told — by a woman he was about to go to bed with, incidentally — that Betty had been having an affair with Jimi Hendrix, who by then the couple had become good friends with. Despite the divorce, Betty kept her husband's name.

And more importantly, she kept his contacts. According to "Tales from the Tour Bus," when Davis was looking to form her own band, she turned to two of her cousins as well as a bevy of great musicians from Miles' contact book to create a group that could turn the ideas she had in her head into a reality on tour and in the studio.

Betty overshadowed Kiss

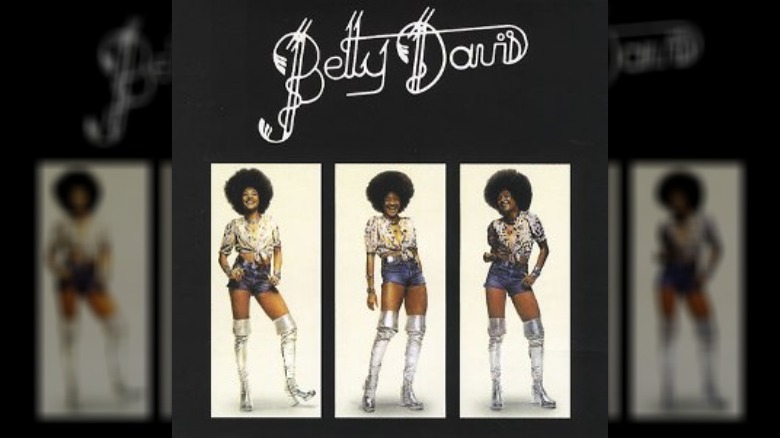

Betty Davis' self-titled debut album was released in 1973, with "They Say I'm Different" arriving the following year. In the meantime, Davis and her band were touring extensively, shocking audiences with the singer's uncommonly sex-charged lyrics, vocals, and stage performances.

Merging funk and rock in a style that had been little explored at that point, Davis and her band were not easily pigeonholed and found themselves performing for both Black and white audiences. Davis herself also grew very close to prominent rock musicians, including Eric Clapton and Robert Palmer, per "Tales from the Tour Bus."

The same source also recalls a notable gig in which Davis and her band attracted the attention of perennial glam-rockers Kiss who — already a big name in the 1970s — invited Davis to be the opening act for an upcoming tour. However, having seen her act, they realized they would be upstaged by Davis' onstage antics, and decided to withdraw the offer. But that wasn't the only time that Davis' undiluted public persona impacted her budding career.

Betty's image held her back

Though Betty Davis and her band were making huge strides in fusing various genres into a new form of funk, the rawness of her image, her vocal style, and her overt sexuality meant that she had difficulty finding an audience in an age when female musicians lacked the empowerment to express themselves in the "nasty" way afforded to men working in the same genres, per "Tales from the Tour Bus." Davis' third album, "Nasty Girl," arrived in 1975, but to little fanfare, and as she and her band recorded their fourth and final album together — which, sadly, would never be released — tensions in the band seemed to herald that their shot at making it big in the U.S. was, sadly, failing.

And according to an interview given to The Washington Post in 2018, Davis' wild stage act and boundary-pushing lyrical content received friction from some unexpected sources, most notably the NAACP, who lobbied promoters to curtail her performances, arguing that they reflected badly on the perception of Black Americans and were morally suspect.

"I thought they were for the advancement of colored people, correct? But they were stopping my advancement. They were stopping me from making a living ... I wrote songs about sex, and that was sort of unheard of then. So that's what I think my influence was. It was very sexually oriented," she told the Post.

Her career was cut short by mental illness

Nevertheless, the four albums Betty Davis produced during her short career ensured she established a cult following, with her music now considered some of the most influential funk records of all time. It was only later that Davis came clean about the trials that she had endured during her recording career and which had scuppered her chance of attaining the stardom she deserved. In a late documentary about her life, "Betty: They Say I'm Different," which rekindled interest in her influential discography, Davis explained: "I told no one of how Miles was violent . ... So I wrote and sung my heart out. Three albums of hard funk. I put everything there. But doors in the industry kept closing. Always white men behind desks telling me to change — change my look, change my sound ... I needed to 'fit in,' or else no contract ... I learned that stars starve in silence" (via The New Yorker).

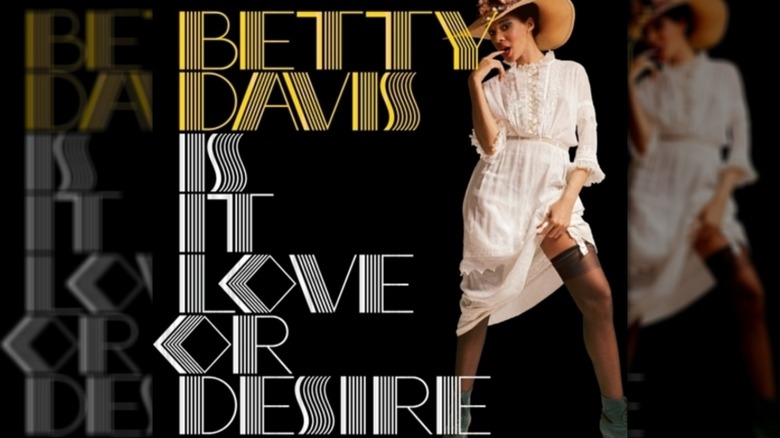

The strains of trying to break into the industry coupled with the trauma her father's death meant Davis suffered a severe decline in her mental health, leading to her hospitalization, according to "Tales from the Tour Bus." Davis never returned to the music industry, though her albums would later be reissued and a lost album, "Is It Love or Desire?" finally released in 2009. Her direct musical descendants include some of the biggest recording artists on the planet today: Beyoncé, Lizzo, and Janelle Monáe all owe her a debt. According to The New York Times, she died February 9, 2022, at the age of 77.