The Forgotten Pennsylvania Oil Tragedy That Killed 19 People

The United States oil industry started on August 27, 1859, per the American Oil and Gas Historical Society. It's such a specific date because that is when the first commercial oil well struck oil. The well was known as the Drake well after the man who found it, Edwin Drake. Drake only had to drill about 69 feet into the ground before coming across oil, and starting a new industry.

According to "The First Oil Well Fire" by Michael H. Scruggs, Drake's discovery started a chain reaction of boom towns popping up in the area where he had found what became known as black gold. People hoping to strike it rich made their way to the banks of the Allegheny in an area that eventually earned the nickname Oil Creek. One of those people who decided to drill for oil in hopes of untold riches was Henry Rouse. In 1861, Rouse discovered a rich oil well, only the excitement was short-lived, as his discovery led to the first oil well fire in the industry's history.

Henry Rouse

According to Warren History, Henry Rouse was born in Westfield, New York in 1824. Rouse was a good student and of good character, noticed by his teachers, who even paid his way through school knowing that based on his character, he would someday pay them back, which he did. Plus interest. Rouse went to law school, but he abandoned a career in law due to a speech impediment.

In 1840, Rouse moved to Warren County in northwestern Pennsylvania where he started teaching in the town of Tidioute. Rouse was paid for his teaching in shingles. He took the shingles and sold them down the Allegheny River in Pittsburgh. This was the first step in what became a successful career in commercial endeavors for Rouse, who went on to produce lumber, owned rafts for transporting materials, and also owned a store in the town of Enterprise, Pennsylvania. Rouse served two terms in the Pennsylvania state legislature in Harrisburg in the late 1850s, but he eventually noticed the burgeoning oil industry in his part of the country and decided he wanted in on it.

The Little and Merrick well

According to Warren History, Rouse decided to build a well in an area nicknamed Oil Creek, an area along the Allegheny River known for its abundance of oil just below the surface. On April 17, 1961, Rouse managed to strike oil just 300 feet below ground in Venango County, Pennsylvania. This particular well was called the Little and Merrick well and it was Rouse's second attempt to strike black gold in the area around Oil Creek.

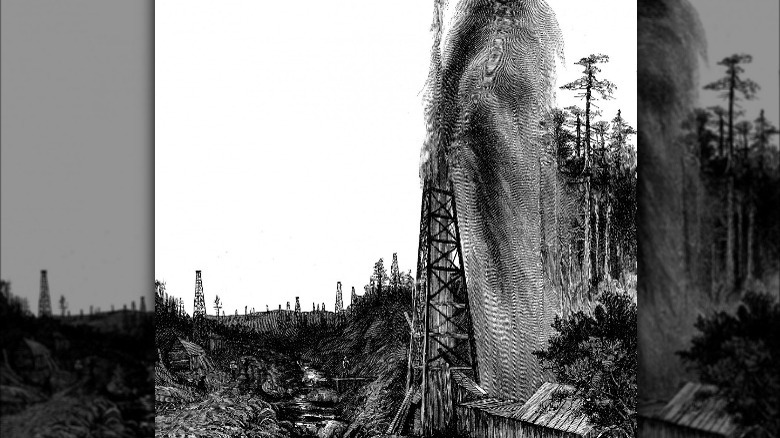

Oil started spewing from the well like a black, viscous, highly flammable Old Faithful. According to the Pennsylvania Center For The Book, Rouse and everyone at the well that day was transfixed by the sight of the oil, with dollar signs in their eyes, except George Dimmock, who ran to find something to store the oil, which was gushing out of the well at a rate of three thousand barrels per day.

The well became a spectacle

A giant geyser of crude oil gushing into the sky is sure to attract attention, and attract attention it did. Television was still about eight decades away, so people living in nearby towns turned to the Little and Merrick well for entertainment. As this was so early in the history of the American oil industry — just two years since the Drake well struck oil — perhaps they didn't realize that it was probably best to observe the well from afar.

According to the American Oil & Gas Historical Society, the onlookers wound up getting splashed by the fountain of black gold. That's more of a nuisance than anything, but things quickly took a turn for the worst. The well exploded, shooting flames hundreds of feet into the air. To this day, no one is sure what caused the explosion. Some have said that Rouse was done in by his own hubris, igniting the blaze while lighting a celebratory cigar. Others have said it was a freak accident set off by a sparking piece of machinery.

The incident

Whatever the cause, the outcome is the same. Nineteen people were killed in the oil well fire. According to Warren History, Rouse was one of them. He was burned to death along with the oil well that was supposed to make him even richer. George Dimmock, who had been there when the well was discovered was also there to watch the disaster unfold first hand, observed Rouse standing closer to the well than anyone was at the time of the blast, and once it happened he dashed toward a nearby ravine. He also dug through his breast pocket to grab important papers and snatched his wallet from his pocket. He threw these out of the fire in hopes of saving them.

"He had accomplished but half a dozen steps when he stumbled and fell, still being within the circuit of the fire," Dimmock said, according to an account discovered by Michael Scruggs and printed in "The First Oil Well Fire." "He buried his face in the mud to prevent inhalation of the flames; then recovering himself bounded up the ravine, falling for a second time completely exhausted at a point where two men barely endured the heat long enough to seize and drag him forth."

The aftermath

Before he died, Rouse was pulled out of the flames, and while he was severely injured and on the verge of death, he was able to pass along his final wishes. He managed to choke out that he wanted his estate to be given to the people of Warren COuntry, many of whom were quite poor (via the Pennsylvania Center For The Book).

The 18 additional dead needed to be tended to, but there was still a raging inferno and an oil well pumping fuel into it. The blaze eventually swallowed the entire farm that the well had been built on, but after 70 hours, they managed to snuff out the flames by throwing dirt and manure on top of it.

The fire at Rouse's Little and Merrick well was one of the industry's first major incidents in the history of the United States oil industry, but it was far from the last. The very nature of working with oil made the prospect of fires erupting part of the job. However, some lessons learned from the fire at Rouse's well have been used to fight oil well fires in the decades that followed.