Inside Harry Truman's Contentious Relationship With General Douglas MacArthur

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

The mid-1940s saw WWII ended in victory for the Allies and America in ascendence. Peace had been restored, the economy was booming, and the outlook for the nation was more positive than it had been in a generation. Across the oceans, American-led reconstruction began in Germany and Japan, former foes who were soon to become close allies and economic powerhouses. But at the same time, the equally victorious (and soon-to-be nuclear-armed) Soviet Union was flexing its proverbial muscles; the USSR was seeking new territory of its own and bolstering allies, such as the communist northern half of the Korean peninsula.

As the '40s continued, two men ensconced in different seats of power would follow paths that would meet, briefly run parallel, and then finally clash in dramatic fashion, impacting not just their own lives and careers, but also the course of the world's next major military conflict: the Korean War. These men were President of the United States Harry S. Truman and five-Star General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, a pair of individuals of vastly different temperaments and pedigrees who would nonetheless be compelled to work closely with one another in trying times.

The relationship (or lack thereof, more accurately) between Truman and MacArthur would lead to the end of the general's storied military career, the plummeting of Truman's approval ratings, and a high-level review of America's command structure, wherein a civilian president serves as commander in chief — a system that prevails today.

Truman was considered by many an unfit and accidental president

Harry S. Truman was indeed an unlikely president in many ways. The 33rd president of the United States of America was, per The White House, born in Missouri in 1884. He was the last POTUS ever elected who did not attend college, per The Washington Post, instead working as a farmer for many years following his graduation from high school. Truman served as a field artillery officer during World War I and then, on his return, he married and opened a haberdashery shop in Kansas. Entering politics, Truman was soon elected as a county court judge and, in 1934, became a senator. But it was his election to the office of vice president during the fourth term of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt that would be of true gravity.

According to American Heritage, the plainspoken, uncontroversial Truman was chosen to replace FDR's former VP Henry Wallace, as many had come to see Wallace as too far to the left. The Roosevelt-Truman ticket was, unsurprisingly, a winner, and FDR remained the steady hand of the nation. That steady hand would go cold only a few months into the start of the new term, and 82 days into his term as vice president, Truman found himself elevated to the presidency, a position many Washington power brokers had never wanted for him. And Truman wasn't entirely sure he wanted it either, saying to a group of reporters on the occasion of his swearing-in: "I felt like the moon, the stars, and all the planets had fallen on me."

MacArthur had a decades-long and decorated military career

Douglas MacArthur was born in Little Rock, Arkansas, in 1880, according to the National Museum of the United States Army. His father was Lt. Gen. Arthur MacArthur Jr., a veteran of the Civil War who later served as the governor-general of the Philippines, a land that would become pivotal to the younger MacArthur's life and legacy.

Douglas MacArthur attended the West Point military academy and, in 1903, graduated at the top of his class. As a young officer, MacArthur served in the Philippines, via History, working as an aide to his father, who would die in 1912. In 1914, now a captain in the U.S. Army, MacArthur saw his first action in operations in Veracruz, Mexico, during the ongoing Mexican Revolution. He was nominated for a Medal of Honor for his conduct there.

But it was during World War I that MacArthur truly came into his own. During the conflict, he earned seven Silver Stars, two Croix de Guerres, two Distinguished Service Cross awards, and an Army Distinguished Service Medal, via the U.S. Army Museum. Between the world wars he held various command roles, including as superintendent of West Point. By the onset of American engagement in WWII, MacArthur had retired from the American military and accepted an appointment as the Philippine army's civilian field marshal. He quickly rejoined America's forces, however, and was promoted to lieutenant general and appointed commander of U.S. Army Forces in the Far East by FDR. It was a role in which he served ably, including in his liberation of the Philippines, the occasion for his famous remark: "I have returned."

Truman turned to MacArthur for leadership at the outbreak of the Korean War

Following Allied victory in the East in World War II, at the behest of the president, Douglas MacArthur stayed in Japan to oversee the demilitarization and reconstruction of America's former foe. He would spend six years serving there with the title Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, via the Wiley Online Library. During these years, operating largely on his own recognizance and without oversight or control from Washington, MacArthur's ego and sense of grandeur only grew, per History Net, as he acted as a sort of "substitute emperor figure." Back in Washington, President Harry Truman, thrust into power as he had been, was content to let the celebrated general handle reconstruction in Japan, much as Secretary of State George C. Marshall — namesake of the Marshall Plan — handled the post-war recovery logistics in Europe, via History.

According to the State Department's Office of the Historian, reconstruction in Japan would fall into three phases, all of which were overseen by Gen. MacArthur. The first, lasting from the war's end into 1947, was largely a punitive phase during which war crimes councils tried, convicted, and punished many members of the defeated Japanese Imperial Army. The next phase was focused on the economic revival of Japan, including breaking up monopolies, reviving industry, and implementing new taxation and inflation management policies. Finally, MacArthur oversaw the establishment of a path forward for Japan in which it would be a partner and ally of the west, with American military bases in place, Japan partially rearmed — this largely due to the new threat of war with communist nations — and mutual security assurances among Japan, America, and other nations.

Truman appointed MacArthur commander of forces in Korea

On June 25, 1950, troops from communist North Korea invaded the democratic South Korea following escalating tensions and several smaller-scale clashes at the border at the 38th parallel. Via History, two days later, on June 27, President Harry S. Truman announced that he would send American air and naval forces to support the allied South against communist aggression. The next few days involved a fever pitch of military and diplomatic planning, including top-level meetings of the United Nations Security Council, which convened with the conspicuous absence of the Soviet Union, an ally of North Korea.

On June 28, the U.N. Security Council approved a resolution calling for the use of force against North Korea. On June 30, Truman upped the American commitment to the cause, agreeing to send U.S. ground forces into the fight. The United States would be placed in charge of all U.N. troops, and on July 8, General Douglas MacArthur was tapped to lead the coalition. Truman was once again entrusting a major operation to MacArthur, not yet appreciating (and indeed how could he?) the level to which the general would operate independently and the lack of respect MacArthur would demonstrate for the American model in which a civilian commander-in-chief is the ultimate director of military policy.

MacArthur mocked official policy early in the war

On August 10, 1950, General Douglas MacArthur made a public statement that promoted his own personal views of how military and foreign policy should be conducted and even seemed to criticize official policies out of Washington. Per a published University of the Pacific thesis, the general's statement in defending his visit to the island of Formosa — modern Taiwan — read in part: "My visit has been maliciously represented to the public by those who invariably, in the past, have propagandized a policy of defeatism and appeasement in the Pacific... which tend, if indeed they are not designed, to promote disunity and destroy faith and confidence in the American nation and institutions and American representatives at this time of great world peril."

To be clear, MacArthur was accusing Americans (politicians in particular) of intentionally damaging faith in the military — a grave claim at any time, but especially during a time of war. What was being said, quite different from an attempt to undermine MacArthur and the military writ large, was that perhaps actions that may goad China into war were a bad idea — actions like visiting a territory in hot dispute, as the island of Formosa was. (And still is.)

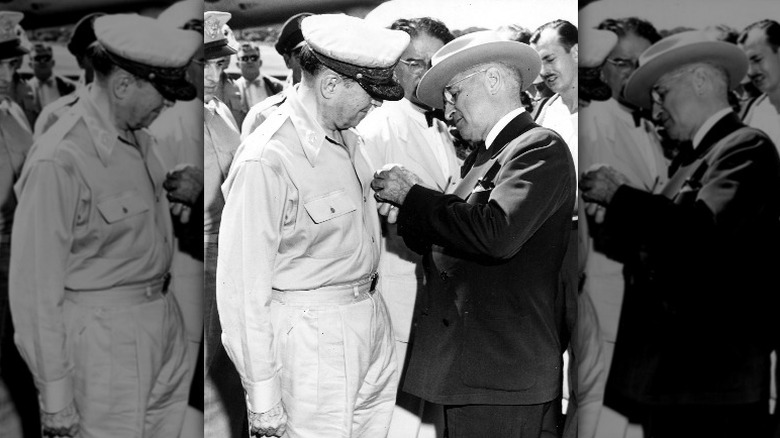

Truman and MacArthur met in person for the first time at Wake Island in October 1950

President Harry Truman and General Douglas MacArthur met for the first time in October 1950. The place of the meeting was Wake Island, in the center of the Pacific Ocean. The meeting was called by Truman, but according to the Los Angeles Times, it was MacArthur who dictated the terms, including the remote location, as he had stubbornly refused to travel all the way from Asia to Washington.

It's been speculated that, for Truman, the Wake Island meeting was largely a political move, via Signals. He met with MacArthur, whom he had recently and flippantly called "God's right hand man," knowing it would look good for him and for his Democratic Party to meet with the celebrated general while the war in Korea seemed to be going well. (The meeting came mere weeks before the midterm elections of 1950.) Following the meeting, via the American Presidency Project, Truman released an official statement that read in part: "I have met with General of the Army Douglas MacArthur for the purpose of getting firsthand information and ideas from him. ... Our conference has been highly satisfactory. The very complete unanimity of view which prevailed enabled us to finish our discussions rapidly, in order to meet General MacArthur's desire to return at the earliest possible moment."

In fact, according to the Los Angeles Times, MacArthur had rushed the meeting, skipped lunch, and left the president, who had travelled nearly 14,500 miles for the face-to-face, enraged and seething.

MacArthur publicly stated that American forces would be home by Christmas

General MacArthur, in his typically confident way of approaching matters, was certain of a quick and easy American-led allied victory in Korea in the early days of the conflict. During that October 1950 meeting, MacArthur famously told President Truman that American soldiers would be "home by Christmas," implying a victory in the war within a matter of just two more months, via BBC News. This statement displays the general's lack of foresight that China would come to the aid of its communist neighbor, which it did mere weeks after MacArthur's assurance of victory before Christmastime.

MacArthur would later call the Chinese entry into the war "one of the most offensive acts of international lawlessness of historic record," according to the book "South to the Naktong, North to the Yalu," but in fact he should have seen it coming. And even in the wake of Chinese involvement — which dramatically shifted the balance of power back to the communists following several months wherein U.N. troops had pushed North Korean forces back in many places — MacArthur remained vainly anchored to his statement. According to the Truman Library, as late as November 29, 1950, MacArthur said to Major General John Coulter that he wanted to "make good on my statement that [American soldiers] are going to eat Christmas dinner at home." They did not.

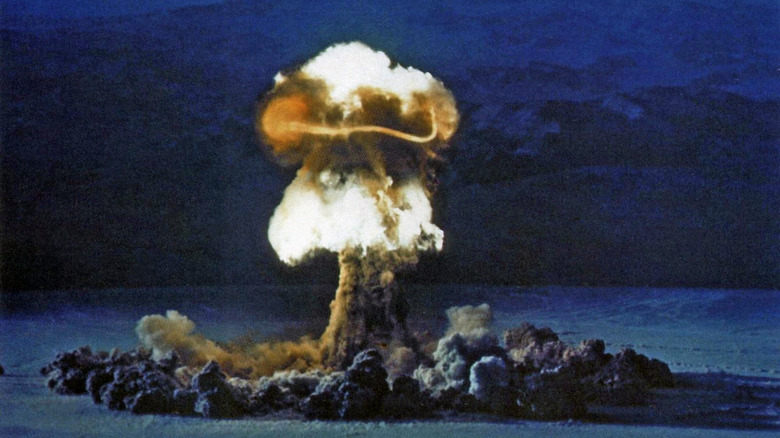

Truman put the option to use nuclear weapons in MacArthur's hands

As even the most casual student of history knows, nuclear weapons have been deployed in aggression precisely two times, these being the atomic bombs dropped on August 6 and 9, 1945, on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, respectively. The United States was the attacker in both cases. Atomic weaponry was arguably the final war winner in World War II; in the Korean War, atomic weapons were nearly used again. And had General Douglas MacArthur remained in power for the duration of the conflict, they likely would have been.

In late November of 1950, despite how General MacArthur had treated him at the Wake Island meeting a month prior, President Truman publicly stated America would take any and all action needed to win the war in Korea, including the use of nuclear weapons, the control of which was to be in the hands of the military commanders in the field, per Smithsonian Magazine. Mark that carefully: In one fell swoop, the president of the United States said he authorized the use of atomic weapons, and that he was comfortable turning over the final decisions about when and where to use them to someone else, that someone being MacArthur.

And none of this was a bluff. The military was well-equipped with nuclear weapons, having a stockpile of some 300 Mark 4 plutonium bombs at the ready, nine of which were transferred to Okinawa, Japan, in April 1951, meaning the Air Force was fully poised to strike if so ordered.

MacArthur often initiated combat maneuvers prior to getting actual authorization

Douglas MacArthur wasn't a man who thought it was better to seek forgiveness than ask permission; he was a man who usually did neither. When it came to the waging of the Korean War, the general often acted with impunity, unilaterally issuing orders that should have required sign-off from Washington and that often had major and lasting implications. According to the National Archives,

Early on in the conflict, the general had ordered munitions shipments to the Korean theater without first seeking official approval, a move that could have been seen as an escalation by North Korea and its allies in China and the USSR. He aggressively pushed for action above the 38th parallel before Washington had signaled willingness for such engagement. And later, after the Chinese had fully and openly entered the war, MacArthur even at one point began dictating his own policies toward the enemy, fully going around the chain of command when he decreed that Chinese forces must surrender or face punitive action from U.N. forces.

The last straw for Truman came in April 1951

President Harry S. Truman relieved General Douglas MacArthur of command in April 1951. On the sixth of that month, according to History, the president wrote in his personal diary: "This looks like the last straw," referencing yet another outrage from MacArthur. In this case, the famous general had sent a letter to the Republican leader of the House of Representatives, Joseph Martin, in which he wrote openly of his differences of opinion with Washington (i.e., with President Truman) on how the war should be waged. The president could suffer the insubordination no longer.

Less than a week after his personal journal entry, President Truman took the momentous step of firing America's most famous and beloved living general. He relieved MacArthur of his command with a statement that read in part: "With deep regret I have concluded that General of the Army Douglas MacArthur is unable to give his wholehearted support to the policies of the United States Government and of the United Nations in matters pertaining to his official duties."

It was Truman's own undoing in many ways as well. Shortly after the firing, his popularity rating plummeted to 22%, a low that has never been matched — not even by Nixon during the Watergate mess, per History. He would not run for office again.

Truman praised MacArthur even after relieving him

Even after the many times MacArthur had spoken against his policies, snubbed him, gone around the chain of command, and acted like he was above the office of the president of the United States of America, General Douglas MacArthur still drew praise from Harry Truman, the POTUS who was loathed by so many for firing him. Per Teaching American History, in a speech explaining why he had relieved MacArthur, Truman said: "A number of events have made it evident that General MacArthur did not agree with [American] policy. I have therefore considered it essential to relieve General MacArthur so that there would be no doubt or confusion as to the real purpose and aim of our policy. It was with the deepest personal regret that I found myself compelled to take this action. General MacArthur is one of our greatest military commanders. But the cause of world peace is more important than any individual."

We now know, however, that in fact on a personal level the president found the general pompous and insubordinate, per Bill of Rights Institute. Truman attempted to mend fences in public by praising MacArthur, but in fact he must have been quite relieved to have removed this highly decorated thorn from his side.

MacArthur later said he would have dropped dozens of nuclear bombs on Korea

Long after his time as an American military commander had come to an end, Douglas MacArthur could not help but speak out about what he would have done differently in the Korean War. According to Express, one thing he would have done would have been to drop as many as 50 nuclear bombs. In an interview the retired general granted author Bob Considine many years after the conflict, he said: "I would have dropped between 30 to 50 tactical atomic bombs on air bases and other depots strung across the neck of Manchuria from just across the Yalu River at Antung to the neighborhood of Hunchun," adding: "That many bombs would have more than done the job."

In the same interviews that informed Considine's 1964 book "General Douglas MacArthur," the former general claimed that with nuclear bombardment followed quickly by heavy troop action, "I could have won the war in Korea in a maximum of 10 days, once the campaign was under way, and with considerably fewer casualties than were suffered during the so-called truce period."

Recall that this confident statement, issued more than a decade after the war ended, comes from the same man who assured Truman that the troops would be home for Christmas in 1950.