Lyncoya: The Tragic Story Of Andrew Jackson's Adopted Creek Son

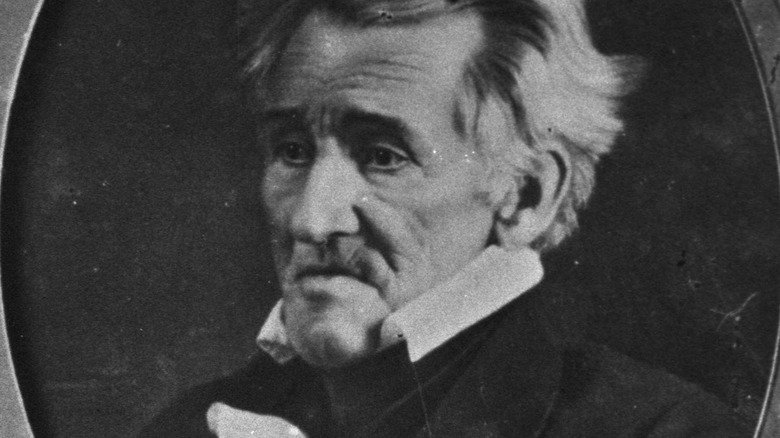

In 1813, future U.S. president General Andrew Jackson took into his care a Native American child, recently orphaned in an attack that Jackson himself had ordered. The infant was named Lyncoya, and he would become known as one of Jackson's adopted sons.

The most infamous legacy of Andrew Jackson is likely the Trail of Tears – a devastating event in which many thousands of Native Americans were forced off their lands and made to walk thousands of miles, with thousands dying before they reached their destination, according to PBS. This horrific event was only one part of the brutal war on the tribes of the Southeast. Jackson's "adopted son" Lyncoya was suggested by some as evidence that Jackson was not a monster, and did not hate all Native Americans.

As described in a report from Slate, the truth about their relationship is largely a historical mystery – though there are plenty of clues about Jackson's true motivations. Lyncoya himself is an even greater mystery. As stated in an interview with historian Dawn Peterson (starting at 11:30), there are no surviving documents written by Lyncoya – we only know about him from Andrew Jackson's letters. How Lyncoya truly felt about the man who ordered his parents' deaths, instigated the decimation of his people, and adopted him into his home and family is unknown.

Lyncoya's parents were killed in a massacre

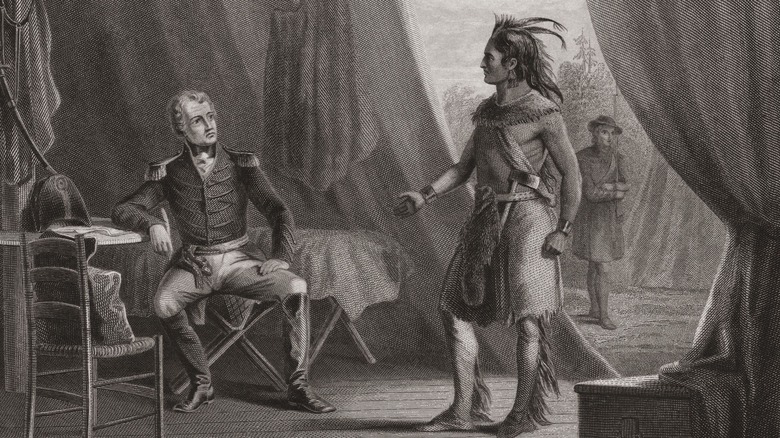

On November 3rd 1813, 1,000 cavalry from the Tennessee militia attacked a village called Tallushatchee, on the orders of future U.S. President Andrew Jackson. The village was Muscogee (sometimes called Creek, as noted by The Muscogee Nation.) By the end of the day, approximately 200 Muscogee people had been killed.

As described at the time in the Columbian Phenix by General John Coffee, who led the attack, they had orders to destroy the Muscogee village completely. Coffee described a fierce battle, in which the Muscogee fought fearlessly to protect their homes and families, but were ultimately overwhelmed by the massive number of attackers. As noted by Slate, the soldiers killed all the men who had lived in the village and set houses on fire. One of the soldiers was frontiersman Davy Crockett, who would later briefly describe the massacre, saying only, "We shot them like dogs."

Many children were orphaned in the attack. As described by the National Parks Service, one of the survivors was an infant boy, still holding onto his mother's body. This baby would soon attract the attention of Andrew Jackson.

Jackson claimed he related to the tragedy

After the attack on the village where Lyncoya and his family had lived, there were only around 80 survivors. As noted by the National Parks Service, they were all taken prisoner – including the infant boy. While General Andrew Jackson had not been physically present at the massacre that killed the baby's parents, he ordered the attack on Tallushatchee village. In a letter to his wife, Andrew Jackson stated that there was an unexpected pang of compassion on his side, for this tragically orphaned child.

It is believed that Jackson's interest in the child was not due to guilt at having been responsible for Lyncoya's parents' deaths, but because he felt that he had experienced similar trauma. As described by The Hermitage, the museum at Jackson's home, Jackson's father died before his son was born. During the Revolutionary War, when Jackson was 13, he and his brothers signed up to fight for the Continental Army. One of the brothers died of heat stroke, while Jackson and his surviving brother were captured by the British. By the time his mother was able to negotiate for their release, Jackson's hand had been slashed by a British officer, and both had contracted serious cases of smallpox — which killed his remaining brother before they returned home. Before he turned 14, Jackson's mother also died, leaving him an orphan. It is believed that when Jackson heard about the orphaned infant from the Muscogee (Creek) village, it reminded him of his own childhood experiences.

Lyncoya was renamed

After the massacre ordered by Andrew Jackson, his army was running low on provisions and was not prepared to care for an infant. It was reported that all they had to give the baby was biscuit crumbs and brown sugar in water. As described by the Huntsville History Collection, it is believed that the child was only three months old. Jackson put the orphaned infant into the care of Colonel Leroy Pope. The child was thereafter sent north to Hunstsville, where, as noted by "Andrew Jackson: The Course of American Freedom, 1822-1832," Pope had his daughter Maria take care of the baby. It would be Maria who would give the child a name.

In May, Jackson and his army went to Hunstsville, where they were greeted as heroes and celebrated in style with a ball, where he was reunited with the Muscogee (Creek) child he had taken from Tallushatchee village. Maria Pope presented the baby to Jackson, as written by Jackson to his wife, "dressed more like a poppet, than anything else" and given the name Lyncoya: he would be known by this name the rest of his life. It is unknown what name his parents gave him, and even Lyncoya himself never learned his true name.

Lyncoya was cut off from his own culture forever

The massacre that killed Lyncoya's family was only the beginning of Andrew Jackson's war on the Muscogee (Creek) people. From 1813-14, Jackson's forces slaughtered and imprisoned more Muscogee people. As stated by Britannica, it ultimately resulted in the Muscogee being forced to surrender a massive amount of territory across modern-day Alabama and Georgia.

According to letters Jackson wrote, he believed that the surviving women from Lyncoya's village who had been taken prisoner wanted to kill Lyncoya, because his immediate family had been wiped out. While many biographies of Jackson accept this narrative, historian Dawn Peterson suggested in an interview with Slate that there wouldn't have been any opportunity for Jackson to find out this information. It is also highly likely that this idea came from Jackson's biased view of what Muscogee families were like, rather than the reality of the situation. Whatever the truth, it is unlikely that Lyncoya was able to spend time with any adult member of his own culture, after his parents' death.

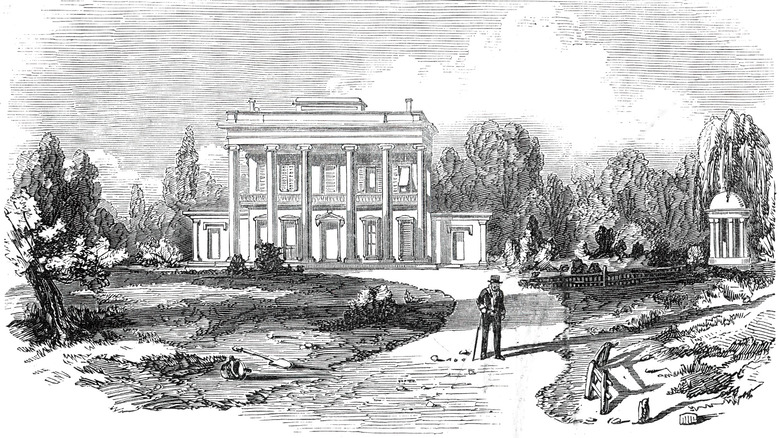

As noted in "Indians in the Family: Adoption and the Politics of Antebellum Expansion," the first biography of Andrew Jackson includes descriptions of Lyncoya while living in Jackson's home. The biographer characterizes Lyncoya as a young man desperately seeking a connection to his past, longing to travel to the Creek nation with any Muskogee people who visited the Hermitage, after the war was over. This early biography is considered unreliable by later historians, however, so it's unclear how accurate this depiction of Lyncoya is.

Jackson brought Lyncoya home as a pet

It is impossible to know for certain what Andrew Jackson's intentions towards the child now called Lyncoya were, according to Slate. Jackson had many enslaved people on his estate, but he wrote to his wife telling her that Lyncoya was supposed to live in the house with his family. That didn't necessarily mean Jackson was planning to make Lyncoya an equal member of his family: when he told his wife that Lyncoya was coming to live at their home, it was indicated he would be more of a pet.

Jackson had a white adopted son named Andrew, who was four years old at the time Jackson sent Lyncoya to live at the Hermitage. In a letter to his wife, Jackson suggested that the baby was a gift for his son, and described him as a "pett" which young Andrew would adopt "as one of the family."

It's unclear how Lyncoya was actually treated by the Jacksons. As detailed in "Indians in the Family: Adoption and the Politics of Antebellum Expansion," Jackson once left Lyncoya with his sister-in-law, who forced the child to live like the people she enslaved. It horrified Jackson to see Lyncoya forced to work, so it is believed that at the Hermitage he was not expected to work in the fields. Historians have suggested that this may have been out of a desire to be seen as Lyncoya's savior, or even a fear that Lyncoya might learn to resist his new "family" from the enslaved Black Americans.

Lyncoya wasn't the only Muskogee (Creek) child in the Jackson home

Whatever Andrew Jackson's purpose in sending Lyncoya home to his youngest white adopted son Andrew was, it was something that he believed in strongly enough to repeat. As noted by Slate, two of Jackson's friends had left their children in his care upon their deaths. These two older boys were known as Andrew Jackson Donelson and Andrew Jackson Hutchings (which meant that, including Jackson and his white adopted son, there were a total of four "Andrew Jacksons" living at the Hermitage.) Soon after Lyncoya moved into the household as a companion – or possibly pet – for Jackson's son Andrew, he acquired two other Muskogee (Creek) children for his other young wards.

One of these children, renamed Theodore, was brought home by Jackson under similar circumstances to Lyncoya. As described by the National Parks Service, it is believed that he was captured after Jackson's army destroyed Littafuchee, another Muskogee village. Tragically, Theodore died soon after his arrival at the Hermitage. Another child, who had been called Charley, was given to Jackson as a gift. Unlike Lyncoya, there are no records about Charley after he moved to the Hermitage, so his fate is unknown.

Lyncoya was not quite part of the family

Because of the lack of records about Lyncoya and a complete absence of anything written by Lyncoya himself, it is impossible to know for certain exactly how he was treated or how much a member of Andrew Jackson's family he truly was. As described in an interview with historian Dawn Peterson (starting at 11:30), it is most likely that he was "somewhere in the margins of slavery and freedom."

It is believed that Jackson and his wife Rachel Jackson were unable to have biological children, leading them to bring wards into their families. As described at 5:00 in the same interview, Jackson used the word "adoption" when referring to his relationship with Lyncoya, although there was not yet a standard legal process for adoption.

It is believed that Lyncoya was educated alongside Jackson's white wards, but that in other ways he was forced to follow the same rules as those who Jackson enslaved. It is unknown whether he was expected to work in the house, or was treated like one of their children. The treatment of other Native American children adopted by white families at the time varied, but also frequently blended the line between family and enslavement. They were sometimes educated formally alongside white children, but also had to sleep in a separate wing of the house from the white family.

Jackson may have used Lyncoya as a political tool

In the context of Andrew Jackson's brutal campaign against Native American tribes like the Muscogee (Creek), it may be surprising to learn that he chose to bring Lyncoya into his home. However, it was not entirely uncommon for a white American family to "adopt" a Native American child. As stated by Slate, Jackson was aware that adopting Lyncoya softened his bloody image, and he used this to his advantage. In 1816, he actually asked a senator to tell the Congress about how well he was educating Lyncoya.

As detailed in an interview with historian Dawn Peterson (starting at 5:00,) Jackson used the word "adoption" to apply to Lyncoya, as did many other white men who brought Native American children into their families. Their motivations were not always as straightforward as the desire to have a child. At this time, a large number of indigenous people, both adults and children, were brought into "Euro-American" households either as indentured servants or slaves. This was a part of an intentional effort to control the tribes whose land they had moved onto, by assimilating them into white families and culture. In an interview with Slate, Peterson explained that white slaveholders that adopted Native American children, "believed that what they were doing was a benevolent act, but also understood it as a form of cultural genocide."

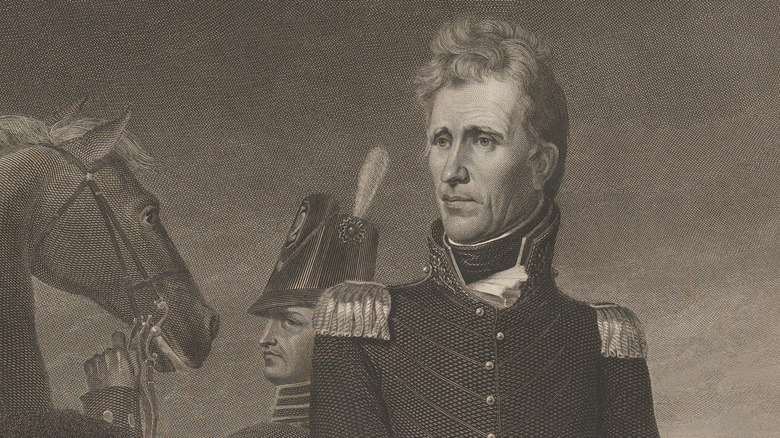

He was unable to go to West Point

Lyncoya was educated alongside Andrew Jackson's white wards, and it seems that Jackson initially intended for Lyncoya's education to continue at the famous United States Military Academy at West Point. Jackson himself had gone to West Point, and it appears that he hoped Lyncoya would follow in his footsteps.

It was not impossible for Native Americans to attend West Point at that time, although it was extremely rare. In 1817, the Academy accepted another Muscogee (Creek) young man named David Moniac. As described by the U.S. Department of Veteran's Affairs, Moniac was the first non-white person ever allowed to attend. He described West Point's leadership as having an unusual fascination with his progress due to his ethnicity — an unpleasant experience that Lyncoya would likely have shared, if he had attended.

As stated by Slate, when Lyncoya was 11 years old, Jackson attempted to "exhibit" his adopted son to President James Monroe and the secretary of war, because he was hoping that they would allow Lyncoya into West Point. Exactly what happened is unknown — but he was never sent to West Point.

He was apprenticed to a saddle-maker

While Lyncoya did not attend the military academy of West Point as Andrew Jackson did, he followed in Jackson's footsteps in another way. When Jackson had been a young man he had trained as a saddle maker (per World Atlas), and it is believed that at some point between the ages of 12 and 15, Lyncoya was also apprenticed to a saddle maker. It's unclear why there was such a drastic change in the future Andrew Jackson was planning for his adopted son.

As detailed in "Indians in the Family: Adoption and the Politics of Antebellum Expansion," Lyncoya's position at the Hermitage had always been an uncertain one, but his apprenticeship solidified it into a labor contract. One possible explanation, stated by Slate, is that it was no longer politically advantageous to Jackson to broadcast that he had adopted a Native American child. The goal of assimilating the tribes had become less popular than the idea that they should be forced off their land, so that it could be transformed into plantations. It has also been suggested that Jackson may have been concerned that, if Lyncoya grew up as a highly educated free man, likely owning land and enslaving people to work it for him, he would become dangerous for Jackson and his political allies. By this time, there were Muscogee (Creek) landowners and slaveholders that were seen as a problem, by those arguing that the Native American tribes were unable to assimilate.

Lyncoya died of consumption

In 1828, Lyncoya died from tuberculosis at 16 years old. As stated by PBS, by the beginning of the 19th century, tuberculosis had killed one out of every seven people that had ever lived. During Lyncoya's lifetime, it was believed that tuberculosis (then often called consumption) was an unavoidable innate condition, which could only be treated with rest and fresh air. In truth, tuberculosis is a highly contagious disease that causes exhaustion, excruciating coughing, and is often fatal without effective treatment.

As noted by the Washington Post, where Lyncoya was buried remains unknown, and it is believed his grave was unmarked. As noted by Slate, a monument was erected on the spot where Tallushatchee village had once been, near where he had been found with his mother's body. This monument names Andrew Jackson as Lyncoya's compassionate protector, claims that he personally "nursed [Lyncoya] back to health," and that he and his wife "adopted, raised, loved, and educated him as their son."

Lyncoya complicates Jackson's legacy

Andrew Jackson referred to the destruction of the village of Tallushatchee and the murder of around 200 people there as "elegant." It was only the first of many attacks on Muscogee (Creek) people, and the brutal mass displacement of many thousands of Native Americans. Despite his brutal campaign of violence, Jackson's decision to bring a single infant survivor of the massacre at Tallushatchee back to his home has led some to view Jackson as an admirable figure. Notably, former Democratic Senator Jim Webb wrote in an opinion piece in The Washington Post, that Jackson could not be considered genocidal when he had "brought an orphaned Native American baby from the battlefield to his home ... and raised him as a son."

Some historians believe that this apparent contradiction in Jackson's legacy was intentional. As noted by The Washington Post, Jackson ensured that the biographers writing about him, in his lifetime, were aware of the story of how he had "rescued" Lyncoya from the battlefield.

Lyncoya was a child orphaned by his adopted father, referred to by his new family as both son and family pet, who died before he ever reached adulthood. As described in an interview with historian Dawn Peterson (starting at 11:00) no documents containing Lyncoya's writing have survived, so how Lyncoya viewed his own life, identity, or relationship with Andrew Jackson remains unknown.