The Messed Up History Of Tuberculosis

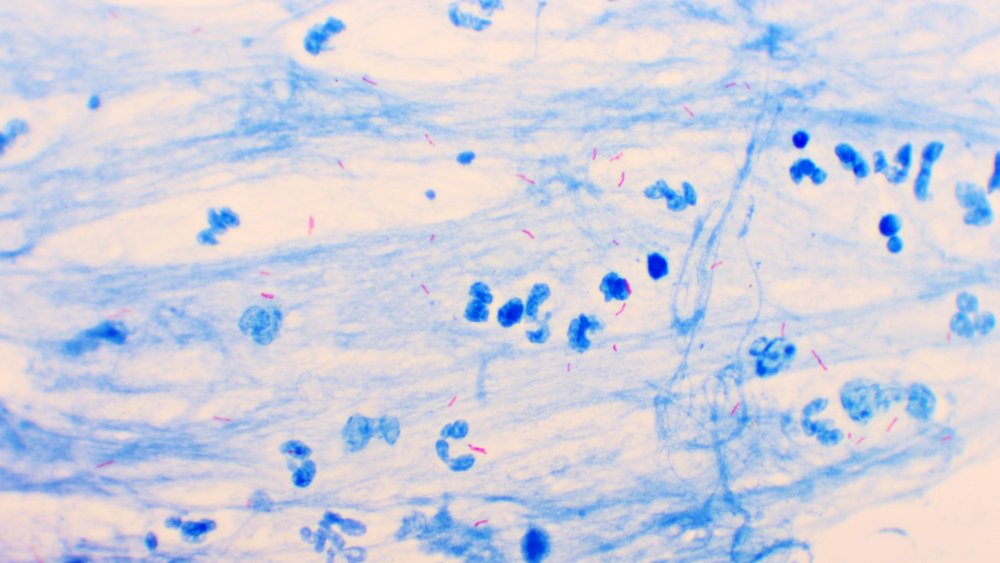

Caused by a bacterium called Mycobacterium tuberculosis, tuberculosis (TB) is one of the deadliest infections for humans on the planet. Over one million people die from TB every year and it can damage multiple organ systems. And while some TB infections are latent, which means that those people with TB infections aren't infectious and are asymptomatic, even latent TB infections can develop into active ones if not treated properly.

Tuberculosis gets its name from the Latin "tuberculum," meaning a small swelling. During autopsies of TB victims, doctors often found small swellings on the victim's organs, most often on the lungs. Since the tubercles were white, TB was called the "White Plague," but it had a number of other nicknames too such as "the Captain of all these men of Death" and "the graveyard cough."

During the Victorian era, TB was so common that people used it as inspiration in their fashion trends, hoping to emulate the look of people wasting away in what is now referred to as "consumptive chic." By the 1900s, beards were even blamed for the spread of diseases and it was claimed that TB was "transmitted via the whisker route." And it's even believed that modern tanning culture comes from the prescription of sunlight for the treatment of TB. This is the messed up history of tuberculosis.

TB has been around for millions of years

Tuberculosis has been around for as long as human history has been recorded. Belonging to the genus Mycobacterium, which is estimated to have originated around 150 million years ago, Mycobacterium tuberculosis is believed to have evolved roughly 3 million years ago.

According to News Medical, this early variant of TB is thought to have originated in East Africa. And although M. tuberculosis is the main mycobacteria responsible for causing tuberculosis, there are four other mycobacteria that can cause TB; M. tuberculosis, M. africanum, M. bovis, and M. microti. It's likely that these strains of mycobacteria shared a common ancestor in Africa between 35,000 and 15,000 years ago.

Modern strains of M. tuberculosis appear to become recognizable between 20,000 to 15,000 years ago. But according to NPR, some scientists such as Sebastien Gagneux suggest that modern tuberculosis may be closer to 70,000 years old.

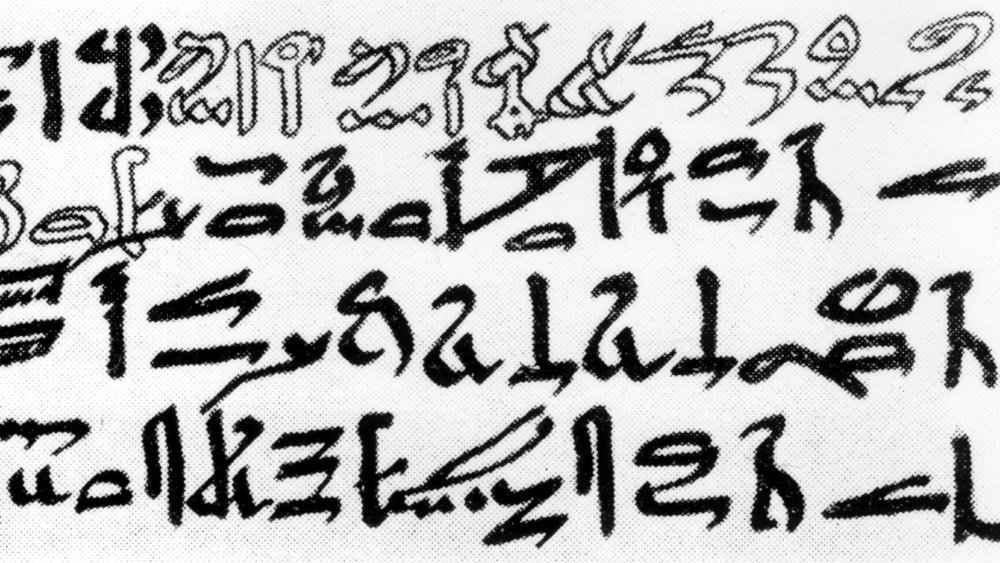

Signs of tuberculosis have been found on mummies from ancient Egypt, dating back almost 6,000 years and tuberculosis is also described in texts from ancient India and ancient China, dating back 3,300 years and 2,300 years respectively.

Symptoms and spread of tuberculosis

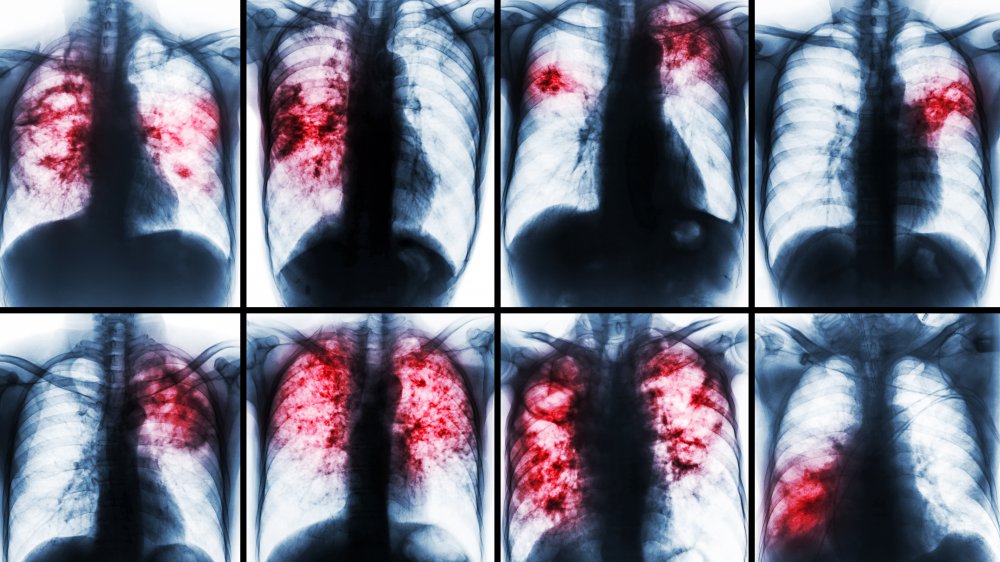

While M. tuberculosis typically attacks the lungs, the bacteria has also been known to affect the brain, spine, and kidneys. And without treatment, TB has a high mortality rate. According to WHO, in the absence of treatment, at least 70% of people with TB die within 10 years of being diagnosed.

While TB was once thought to be hereditary, in 1882, Robert Koch discovered that TB was caused by M. tuberculosis. Now it's known that M. tuberculosis is transmitted through the air via respiratory droplets while speaking or coughing. These droplets can stay in the air for hours and, according to the Guardian, while some diseases like measles can only be caught once, recovering from TB doesn't give one lasting immunity.

According to the CDC, primary symptoms of TB include pain in the chest, a bad cough lasting over three weeks, and coughing up sputum or blood. Other symptoms include fever, weakness or fatigue, and weight loss.

With treatment, those with drug-susceptible TB have an 85% success rate of recovery. With drug-resistant TB, the success rate of recovery falls to 56% globally.

Animals can get TB too

Humans aren't the only ones that suffer from tuberculosis. Evidence of TB has been found in elephants, bison, and birds. According to Nature, there's even a study that claims that seals are responsible for bringing TB from the African continent to the American continents. While this study has been criticized for ignoring work that presents contradictory conclusions, the presence of TB in a variety of animals is notable. And while the presence of TB in humans has been studied for hundreds of years, the study of TB in animals, such as elephants, is relatively recent.

TB can also be found in deer and cattle, though it is caused by M. bovis rather than M. tuberculosis. However, M. bovis has been known to affect humans as well.

Modern animals aren't the only ones susceptible to tuberculosis. There's also evidence that prehistoric animals may have suffered from TB as well. According to IFLScience, analysis of rib bone fossil fragments from a Proneusticosasiacus, a marine reptile from the mid-Triassic, revealed lesions that may have been the result of pneumonia. In humans, these lesions are only seen in those with TB, so it's possible that this animal represents one of the earliest cases of TB. There are additional discrepancies in the Proneusticosasiacus's vertebrae, which are consistent with Pott's disease, a form of TB that attacks bones of the spine.

Mummified tuberculosis

Evidence of tuberculosis has been found in a variety of forms from ancient Egypt. According to News Medical, skeletal deformities indicative of Pott's disease have been found on Egyptian mummies from between 2400 and 3400 BCE. Molecular studies also show that TB is present in almost one-third of Egyptian mummies. As reported by Microbiologia Medica, one of the most convincing signs of TB was found in the mummy of the priest Nesperehen, discovered in 1881.

The earliest reference to TB in ancient Egypt comes from a papyrus dating to 1550 BCE. Known as the Ebers Papyrus, in this medical papyrus, tumors are described that are believed to be a result of tuberculosis, though they were once thought to be describing leprosy.

The American Review of Respiratory Disease claims that there are also artistic representations of TB from ancient Egypt. People with spinal deformities are often depicted in Egyptian iconography, which was likely a result of Pott's disease.

Tuberculosis in North and South America

Tuberculosis existed in North and South America before Europeans began colonizing the continents, but it's still unclear when or how the bacteria spread across the Atlantic. While the strain of M. tuberculosis recovered in skeletal remains from pre-colonization America doesn't match the strain believed to have been brought by European invaders, there's evidence of the disease's presence long before the Europeans brought their own version.

According to Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz, skeletal remains with lesions resembling those consistent with TB have been found in a variety of different sites across the American continents. The earliest evidence of TB on the American continents was found in mummified remains recovered from the Atacama desert in Chile, dating back to the first millennium CE.

However, there have notably never been any Mayan skeletons found with signs of tuberculosis. There are multiple hypotheses for this, though it's unclear whether this is a result of a low incidence rate or poor bone preservation.

Medieval tuberculosis

While the written record of TB in the Middle Ages is sparse, there is archeological evidence from across Europe. In the medical writings that do exist, TB was referred to as the "White Plague," consumption, or phthisis, which meant "wasting." The term "consumption" was also used because the disease gave the impression of consuming its victims as they shed weight.

According to the Journal of Military and Veterans' Health, while it wasn't known that scrofula was a form of TB, it was also associated with consumption, though from the perspective that it was caused by gluttony. Now known as tuberculous cervical lymphadenitis, scrofula was once referred to as the "King's Evil" and was treated with the "royal touch."

Per the Royal College of Physicians, monarchs would touch sick people and offer a seemingly painless and instant cure. The practice was considered to be demonstrative of the king's divine right to rule. During one Easter Sunday, Louis XIV of France was said to have once touched about 1600 people. And since scrofula lesions sometimes went into spontaneous remission, monarchs were credited with providing miracles.

The last British ruler to touch their subjects for scrofula was Queen Anne who ruled from 1702 to 1714, and in 1712, she ended up touching a young Samuel Johnson who had contracted what is believed to be scrofula.

Tuberculosis progresses through the ages

The contagious nature of tuberculosis was detected as early as the 16th century when Girolamo Tracastoro suggested that clothing and bedsheets might contain contagious particles. And according to "The History of Tuberculosis" by Thomas M. Daniel, once René Théophile Hyacinthe Laennec invented the stethoscope in 1816, the pulmonary effects of the disease were finally able to be identified. The belief that TB was infectious was primarily held in Southern Europe. In Northern Europe, TB was still considered to be hereditary.

According to the Journal of Preventive Medicine and Hygiene, during the 18th century, Western Europe suffered from a TB epidemic with a mortality rate of 900 people per 100,000 per year. Death rates were higher among young people, and as a result, TB was called "the robber of youth."

During the following century, death rates stayed consistently high across cities, reaching upwards of 800-1,000 per 100,000 people per year. As the Industrial Revolution progressed into the 19th century, along with it came poorly ventilated housing, deprived work conditions, and poor sanitation, which allowed for the disease to proliferate.

When tuberculosis was fashionable

Because of the prevalence of tuberculosis, the appearance of wasting away that it gave people began to be romanticized and considered fashionable. The thin, pale face, glossy eyes, and rosy cheeks that were considered the pinnacle of beauty were actually symptoms of the low-grade fever and loss of appetite caused by tuberculosis. When Edgar Allan Poe's wife Virginia coughed up blood while playing the harp, Poe considered her sickness as "a strange additional charm, which rendered more ethereal her chalky pallor and her haunted, liquid eyes."

According to Hyperallergic, even though tuberculosis was an epidemic among all types of people, it was especially associated with "respectable women" and was considered an elegant and aristocratic disease. Even Lord Byron wished that he could die of consumption so that the ladies could say "see that poor Byron — how interesting he looks in dying," per Science Museum.

Popular Science reports that women would even effectively poison themselves in an attempt to get this look using belladonna, to dilate their pupils, and arsenic, to lighten the skin. Dresses and corsets also tended to emphasize the emaciated bodies that tubercular victims had.

TB's prominence in art

Tuberculosis is featured and romanticized in countless works of art. Emily Brontë, who died of tuberculosis herself in 1848 at the age of 30, includes several tubercular characters in Wuthering Heights, including Cathy, whom she describes as "rather thin, but young and fresh complexioned and her eyes sparkled as bright as diamonds." The character Smike in Charles Dickens' Nicholas Nickleby also succumbs to tuberculosis. And although authors avoided using the word "consumption," descriptions of pale heroines in decline became more and more common.

TB also appears throughout La Bohème, an opera by Giacomo Puccini, and is responsible for the death of Mimi. According to The Lancet, TB is also featured in The Magic Mountain by Thomas Mann, which is set in a Swiss sanatorium. Nuances of suffering from tuberculosis, such as the Blue Henry, a flask for coughing up sputum, are also mentioned in Mann's novel, demonstrative of the ubiquity of tuberculosis.

The Collector says tuberculosis was also depicted in visual artworks such as 1858's "Fading Away" by Henry Peach Robinson and 1907's "The Sick Child" by Edvard Munch. Many artists and writers themselves succumbed to tuberculosis, which solidified its association with the arts.

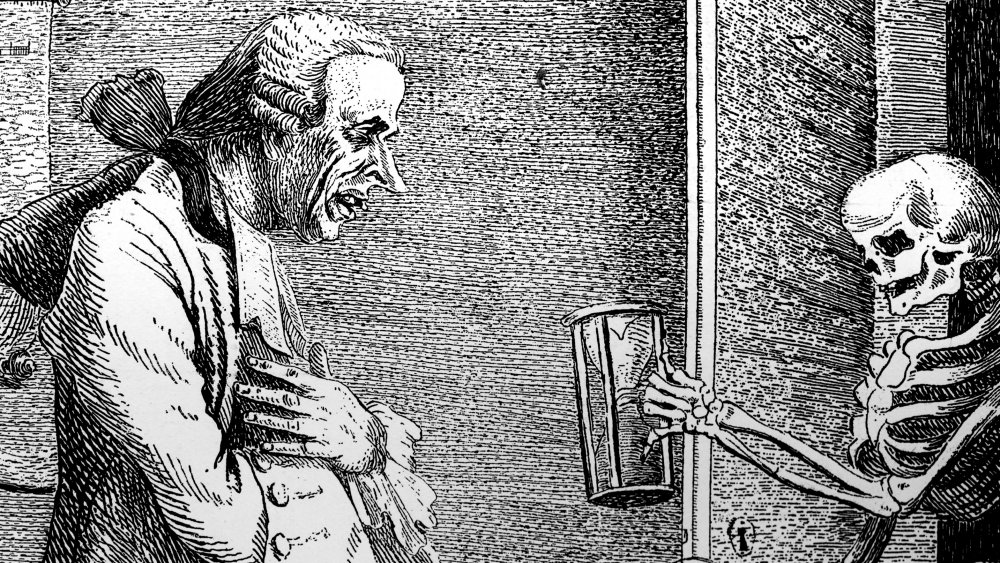

Absolutely mind-boggling treatments for TB

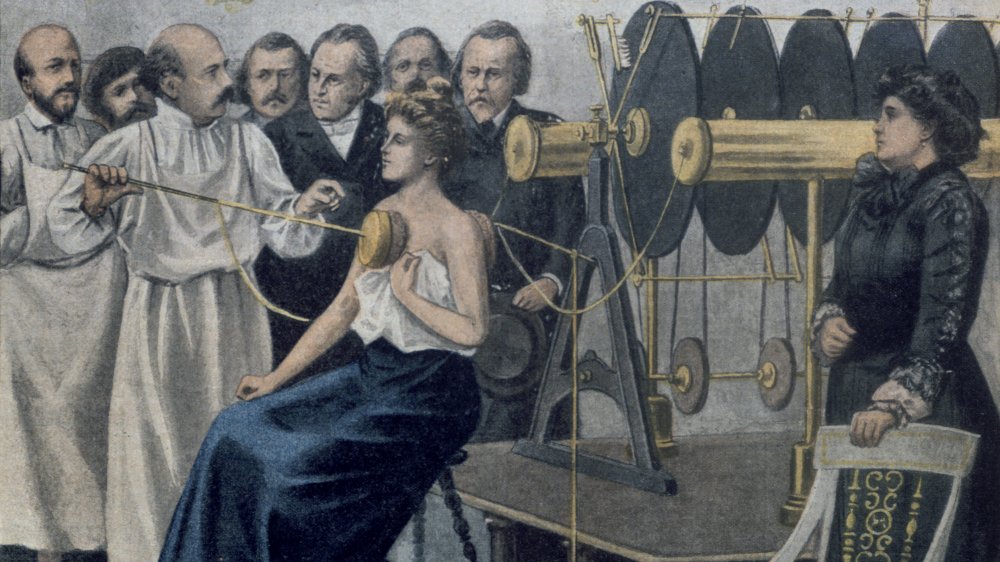

TB wasn't effectively treated until streptomycin and para-aminosalicylic acid (PAS) started being used in 1944. Up until that point, people with TB were subjected to a variety of methods ranging from dietary changes, herbal concoctions, bleeding, sunlight therapy, and rest stays in sanatoriums. According to The Lancet, mountain climbing and horseback riding were also recommended as beneficial exercise towards the treatment of TB. Even electricity was used as a treatment.

In "A Doctor's Dilemma" by George Bernard Shaw, one of the characters even describes the treatment of TB as "a huge commercial system of quackery and poison." This certainly applies to the experiments of Dr. Joseph Howe of New York City. According to Popular Science, in 1873, Dr. Howe tried injecting 1.5 ounces of goat's milk into the veins of a person infected with TB. During the late 1800s, milk transfusions were frequently attempted and often had disastrous and deadly effects.

Once Robert Koch attributed TB to bacteria in 1882, sanatoriums began to be increasingly used for TB treatment. According to The Atlantic, sanatoriums were used to isolate people with tuberculosis but they were also intended to "create a more favorable treatment milieu," since it was believed that lifestyle adjustments would allow people infected with TB to manage their diseases better.

The United States of tuberculosis

While some places didn't suffer from the TB epidemics of the 18th and 19th centuries that plagued Europe, the North American continent was similarly wracked with repeated epidemics. According to PBS, by the 19th century, TB was responsible for killing one in seven out of all the people that had ever lived. Between 1810 and 1815, TB accounted for over one-fourth of the deaths in New York City alone. By 1900, TB was the second leading cause of death after influenza and pneumonia.

According to the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, by the time the American Sanatorium Association was founded in 1905, there were over 100 sanatoriums with over 9,000 beds for people with TB in the United States. Within 50 years, there were over 100,000 beds allocated for the treatment of TB.

Despite the prevalence of the epidemics, per the IZA Institute of Labor Economics, between 1900 and 1930, the TB mortality rate in the United States fell by more than 60%. This drop was likely due to the public health campaign against TB that was led by medical professionals as well as laypeople. This campaign was almost entirely funded through Christmas Seals, which also went towards funding sanatoriums.

The beginning of TB vaccination

In 1900, French bacteriologists Albert Calmette and Camille Guérin began researching a vaccine for TB at the Pasteur Institute in Lille. While they were ready to start a vaccination trial in cattle in 1913, their experiments were interrupted by the start of World War I. They managed to keep working despite the German occupation and by 1919, they had finalized their TB vaccine with a tubercle bacillus that didn't produce TB. They called their vaccine Bacille Bilie Calmette-Guerin, though they later took out "Bilie," rendering it the BCG vaccine.

According to "Tuberculosis Vaccine Development" by Elizabeth M. MacDonald and Angelo A. Izzo, the first human trials occurred in 1921 and resulted in few adverse side effects. The non-viral strain was then sent to various laboratories around the world and as the vaccine was propagated out of various countries, there emerged different variants of the BCG vaccine. Unfortunately, due to this variability, not all vaccine strains ended up being equally effective.

According to Encyclopedia Britannica, the vaccine is meant to be given to infants only and most countries today require that the vaccine is given while a person is young since it is less effective on adults. And while the vaccine's effectiveness can last upwards of 40 years, it's mostly effective against miliary and meningeal TB rather than pulmonary TB.

The Lübeck disaster

In 1930, a tragedy befell Lübeck, Germany that undermined the integrity of the BCG vaccine. Known as the Lübeck disaster, After an attempt to vaccinate a large number of infants between 1929 and 1930, almost 83% ended up becoming infected with TB. According to The History of Vaccines, out of 252 vaccinated, 72 infants died from TB. Another 135 were also infected but were able to recover.

An inquiry was promptly set up by the German government into whether or not the vaccine itself was at fault, led by Professor Bruno Lange of the Robert Koch Institute. After 20 months of investigations, their report determined that the BCG vaccine itself wasn't at fault and that the infections had been due to contamination of the vaccine by virulent tubercle bacilli.

The contamination was found to have occurred in the Lübeck tuberculosis laboratory, and as a result, both Professor Deycke and Dr. Alstädt, who had been responsible for the vaccination attempt at Lübeck, were convicted and imprisoned. Although Calmette and Guérin hadn't been responsible for the error, they came under a great deal of fire and confidence in the vaccine was compromised.

Tuberculosis today

Although the BCG vaccine is only 70-80% effective against some forms of TB, it was invaluable towards slowing the spread of TB. And in 1943, Selman Waksman discovered streptomycin to be the first effective treatment of TB. However, although the first person was cured of TB in November 1949, subsequent people with TB ended up requiring PAS in addition to the streptomycin since the tubercle bacillus had become resistant.

Despite the new drug developments in the following decades, TB continues to build its resistance to this day. Over one million people die every year from TB, with upwards of 10 million people falling ill from TB worldwide. And upwards of 20% of TB cases are due to multidrug-resistant TB (MDR-TB). According to Buzzfeed, MDR-TB may require upwards of two years of treatment.

Despite the global knowledge on how to treat TB, according to WHO, almost a third of people with TB don't have access to quality care. There continues to be a worldwide effort towards eradicating TB, but from 2016 to 2017, the mortality rate declined by only 3.9% and from 2017 to 2018, TB-related deaths dropped from 1.6 million deaths to 1.5 million.