The Messed Up Truth About The 1980s Music Industry

The 1980s were a wild time. Digital technology was improving on all fronts, fashion was neon and outrageous, hair was big, and excess was everywhere. Musically, the decade saw the dawn of exciting new genres like electropop, new wave, and hip hop, as well as the birth of the pop megastar: Michael Jackson, Madonna, and Prince became known as "the holy trinity of pop," as per NME.

In fact, those 10 years had such a lasting effect that people still love the '80s to this day. In 2010, an 11,000-person poll by Music Choice (via Music News) determined that the '80s was the most popular musical decade. Indeed, shows like "Stranger Things," movies like "Top Gun: Maverick," and the popularity of modern artists like The Weeknd, Dua Lipa, and Harry Styles demonstrate that our collective '80s nostalgia is still strong.

But it wasn't all DayGlo and John Hughes movies. When the decade began, people continued to enjoy rock music but, per AllMusic, conventional '70s disco had fallen out of mainstream favor. A global recession was underway (per Federal Reserve History), and, according to Harold L. Vogel in his book "Entertainment Industry Economics," record sales were way down. The music industry took action to save itself, and the results weren't always tubular. From moral panics to the MTV color barrier to rampant commercial greed, here is the messed up truth about the 1980s music industry.

The music industry waged war on mixtapes

Cassette tapes were all the rage in the '80s, owing to their portability and the recent invention of the Sony Walkman and boombox (per Jehnie I. Burns in her book, "Mixtape Nostalgia"). According to Diffuser, an affordable dual tape deck that could record material from one cassette onto another soon launched –- and home recording was born. Mixtapes –- in which songs were recorded from albums or off the radio and assembled into primitive playlists –- became a hallmark of '80s youth culture.

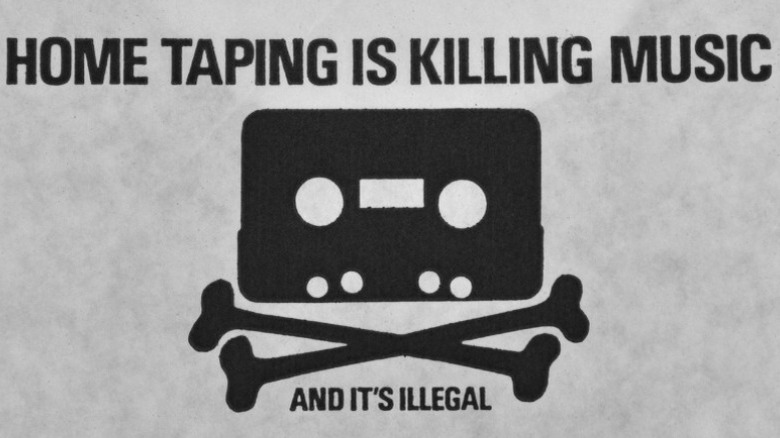

But, while it seems ridiculous now, the music industry viewed home recording as a major threat to profits. According to The Washington Post, record sales were down in 1979, and label executives were desperate for a scapegoat. Shortly after the advent of the dual tape deck, the British Phonographic Industry (BPI) — a trade group that represented most of the United Kingdom's record labels — launched an aggressive ad campaign bearing the slogan: "Home Taping Is Killing Music –- And It's Illegal" (per Diffuser). The slogan, which occurred alongside a dramatic cassette tape Jolly Roger, was printed on many album sleeves and cassettes in the early '80s. The BPI pushed for taxes on blank tape sales to recoup losses, and CBS even sued the creators of tape copying equipment, as per Mondaq. Both attempts both ultimately failed.

A federal government study determined that the majority of home taping involved transferring already-purchased music for portability (per The Washington Post). According to Burns in "Mixtape Nostalgia," the campaign was also widely ridiculed by musical artists –- The Dead Kennedys even released a cassette that read "Home Taping Is Killing Music Industry Profits!" on one side and "We Left This Side Blank So You Can Help" on the other.

Music videos kinda did kill the radio stars

On August 1, 1981, MTV (Music Television) launched in North America –- and it changed everything (per Britannica). The network's first music video, The Buggles' "Video Killed the Radio Star," now seems kind of prophetic. As the network gained a foothold, music videos became so popular that other music channels like Much Music and VH1 soon followed. But there was a major problem.

According to Dale Andrews in his book "Digital Overdrive," video had in fact killed the radio star –- or at least completely changed the rules of the game. Before MTV, most artists were heard but rarely seen. Now, with music videos serving as the ultimate promotional tools, image became just as important as the music –- arguably even more so. Simply making music was not enough. Artists also had to look attractive or interesting and sometimes even act. Those who mastered the visual aspect outperformed all others, regardless of musical ability. And there was another problem.

Because music videos were considered advertisements for artists, no one made any money off of them. In fact, according to singer-songwriter Ian Tamblyn in his speech at Trent University (via Roots Music Canada), artists had to pay for their own music videos –- and making one worthy of airplay wasn't cheap. Because music videos became expected in the '80s, labels would front the artists money to produce them, later recouping the expense out of their royalties. As the decade progressed, production costs became astronomical. To give you an idea, Michael Jackson's 1987 video for "Bad" cost $2.2 million to produce (per HowStuffWorks). In the end, only a select few good-looking, fashionable, rich, or already signed artists were able to keep up with the industry.

The expensive CD was born, and vinyl almost went extinct

In 1982, per Britannica, Phillips and Sony teamed up to release the compact disc –- more commonly known as the CD. According to PBS, record companies claimed CDs offered superior sound quality and durability when compared to vinyl. In his book "Entertainment Industry Economics," Harold L. Vogel notes that the quality of vinyl had become notoriously poor in the late '70s, which contributed to low album sales. Record companies hoped that the technologically advanced CD would inspire people to buy music again.

But when CDs first launched, they were only for the wealthy. According to Billboard, a CD player in 1982 was priced at $750, which is about $2,100 today. CDs themselves were around $15 each, according to PBS -– about $45 today. Despite CDs being relatively cheap to produce, record companies justified the high price, citing the audio superiority they provided and the added cost of building new manufacturing facilities. And, of course, a large percentage of the profit from each CD sale went directly to the record company, as per The New York Times.

Still, it was hardly much incentive to swap out your entire vinyl collection. But in 1983, with the launch of more affordable players and the slow decrease of CD prices, that's exactly what started happening. Vinyl was in trouble. By 1984, cassette sales surpassed vinyl sales, as per Quartz. And in 1988, according to MTV, CDs outsold vinyl. As the '80s drew to a close, vinyl had become a rare sight at record stores.

MTV had a problematic color barrier in place

When MTV first launched, the network played pretty much any video they could get their hands on (via SBS) –- but, still, very few by Black artists. So, in an interview with MTV in 1983, David Bowie called them out for it. The network fumbled for a response. According to The Washington Post, the reasons given included MTV focused on rock music, Black music would alienate many viewers, radio segregated music racially so it was an accepted practice, and Black artists were not making music videos.

A notable example of MTV's color barrier was the network's curious omission of Rick James' "Super Freak." Despite the song being a top hit in the United States in 1981, MTV was not playing the music video for it. James declared this "blatant racism" in a 1983 interview (via Jet Magazine). He also noted that MTV had no problem playing music videos for obscure white punk bands who didn't even have a label.

The color barrier came crashing down later in 1983 when, according to Yahoo!, CBS head Walter Yetnikoff threatened to withhold videos from his label's other artists (which included Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel, and Cyndi Lauper) to get the network to play Michael Jackson's music video for "Billie Jean." MTV complied, and "Billie Jean" became a huge hit, launching Jackson to stardom. (Although Les Garland, MTV's cofounder, told Jet Yetnikoff putting on the pressure was a myth, and he saw value in Jackson's video right away.) MTV later aired his video for "Thriller" –- which is widely considered the greatest music video ever made (even by MTV in 1999, as per Rock on the Net). Videos by Black artists like Prince and Whitney Houston were soon in heavy rotation on MTV.

Digital technology made everything sound the same

Music of the '80s has a very distinctive sound. Whether you're head-banging to arena rock like Journey or grooving to the seductive synth-pop stylings of OMD, you'll know it was recorded in the 1980s. But why is that? As it turns out, the '80s saw several key developments in production technology that are easily heard in its music.

According to Popular Mechanics, one such invention was the LinnDrum machine, which allowed the digital sampling of real drum beats. Its ubiquitous presence can be heard in a great many songs in the '80s, including Frankie Goes to Hollywood's "Relax." The sampler was another '80s staple, allowing just about any instrument to pop into a song at the push of a key. And then, of course, there is gated reverb — which is responsible for the crashing drums on Phil Collins' "In the Air Tonight"– as well as the now-legendary synthesizers heard in a-ha's "Take on Me" (and just about every '80s song, really). Producers had found a formula that worked and stuck with it.

But all of these new effects gave '80s music a feeling of over-production, especially when compared to the more organic sounds of the 1970s. Love it or hate it, digital technology resulted in a decade's worth of music that all sounded ... kinda the same. According to a 2015 study published in The Royal Society, a computer program scanned 17,000 top hits from 1960 to 2010, examining elements of tonal qualities and chord progressions. The study found that the mid- to late-'80s (precisely when all of these effects saturated the market) was the least diverse era of mainstream music in the last 50 years.

Record labels resorted to shady Mafia dealings to promote songs

It turns out that payola — a crime in which commercial radio stations are bribed to play songs without disclosing they have been paid –- was not just a thing of the '50s and '60s. According to The Los Angeles Times, record labels in the mid-'80s regularly hired independent promoters to influence radio program managers to play certain songs, spending around $60 to $80 million a year on such endeavors. In exchange for play, promoters offered everything from cash to cocaine to sex workers.

In 1986, a federal investigation into payola exposed Joe Isgro, whose Los Angeles music promotion business made $10 million a year in the 1980s, as per The Hollywood Reporter. Isgro was indicted in 1989, but the case was dismissed in 1990 (per MTV). According to The New York Times, he was later revealed to be a member of the Gambino crime family, aka the Mafia. And he was just the guy they caught.

According to Fredric Dannen in his book "Hit Men," major record labels worked regularly with a group of music industry mobster middlemen known as The Network in the '80s. When they needed to ensure a song was played on the radio –- or, worse, that another song was not played –- they contacted members of The Network to make it happen. Following all the bad press, record labels quickly off-loaded all of their independent promoters (per The Washington Post).

Artists were shamelessly used to sell products

If music videos were commercials for artists, artists themselves could become commercials for so many things. In a decade thoroughly enamored with television, TV commercials became key to selling products. And who better to model them than music's megastars?

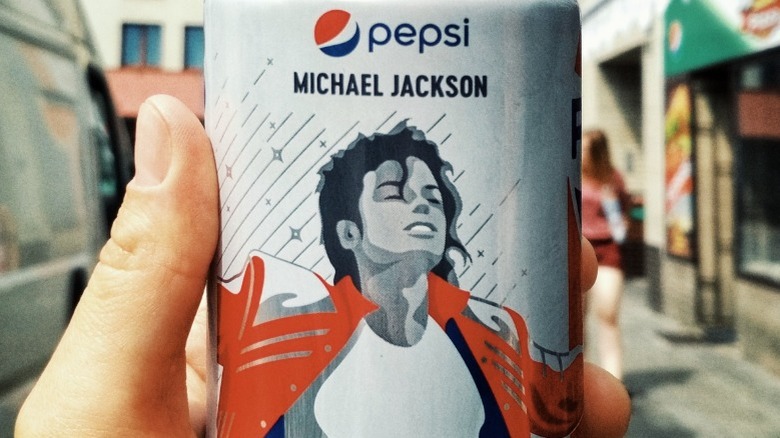

According to Billboard, Michael Jackson made history again when he signed a $5 million deal with PepsiCo in 1983 –- the biggest celebrity endorsement yet. Jackson rewrote "Billie Jean's" lyrics as an ode to Pepsi, and in exchange Pepsi sponsored his U.S. tour. According to Brian J. Murphy, the VP of branded entertainment at TBA Global, the integrated marketing strategy was ground-breaking. "You couldn't separate the tour from the endorsement from the licensing of the music, and then the integration of the music into the Pepsi fabric," he said. The results were astounding: Pepsi turned $7.7 billion in sales that year. When Jackson released his album "Bad," they were quick to sign a second deal with him –- this time for $10 million.

But marrying your product to an artist can have unintended consequences. According to The Pop History Dig, Pepsi's 1989 deal with Madonna backfired when the wholesome commercial they shot with her hit the airwaves one day before she released her controversial religious-themed music video for "Like a Prayer." Amid threats of product boycotts, Pepsi promptly canceled the deal. Calamity also ensued in 1987 when, according to CBC Radio, Anheuser-Busch tried to bring Michelob beer sales up by featuring Eric Clapton in a commercial. Unfortunately, Clapton entered a rehab facility to treat his alcoholism later that same year. Needless to say, it was not a good look for Michelob.

The music industry experienced a boom but artists still didn't make that much

By the mid to late '80s, record companies were making enormous profits, and album sales were increasing each year, as per Digital Music News. Yet, for some reason, artists were still making the same as they were before –- which wasn't much, comparatively.

CDs, which sold at a huge profit margin, were a big part of the industry's growth. But the majority of this money went to the record label, with most artists being awarded less than 5% of every CD sale, per Pitchfork. To make matters worse, labels also charged artists for the use of new technology while reducing their royalties by 20%, according to Steve Knopper in his book "Appetite for Self-Destruction." Despite CDs costing about $8 more than a vinyl record, artists made around 81 cents per CD sale. And then, of course, there were the hefty advances labels provided for promotional music videos, which often had to be recouped before artists saw a dime (per the U.S. IRS in "Entertainment: Audit Technique Guide").

When it was all said and done, royalty rates stayed around 10% for most artists –- only the decade's biggest stars made over 35% (per AWAL). But a few '80s artists successfully fought back against this perceived injustice. According to Refinery29, once Madonna discovered that much of her profit came from songwriting royalties, she ensured that she was listed as a co-writer on every song she sang. Still, even Madonna only made 20% in royalties during the '80s.

Underground artists were overlooked

According to GQ Magazine, music in the 1980s was overseen by only six major labels. Together, they controlled 80% of the music industry and determined what was mainstream based on what sold, according to a 2021 study in The French Journal of British Studies. For much of the decade, the main product was electronic pop music. But pop was far from the only type of music being produced in the '80s. Many artists making different music didn't fit with the mainstream and were confined to the underground scene.

Per Michael Azerrad in his book "Our Band Could Be Your Life," underground artists gained followings through touring, college radio stations, and mentions in fanzines. They would often sign with independent labels, whose goals were promoting creativity rather than commercial success. According to the French Journal of British Studies, most indie artists played guitars and physical instruments as a way of rebelling against the synthesizers and digital sounds that dominated the mainstream. The Smiths, who became very popular in the '80s indie scene, represent a great example of this phenomenon.

Many underground artists were overlooked by major labels in the '80s. Their music became known as a new genre: alternative rock, according to Dave Thompson in his book "Alternative Rock." Its very name suggested opposition to the mainstream. Yet, oddly enough, many of these artists would later become mainstream in the '90s –- in fact, grunge grew out of the underground '80s scene, as per Britannica.

A group of angry mothers tried to censor music -- and it worked

According to a 2020 study published in American Journal of Criminal Justice, trouble started brewing in the mid-'80s when Tipper Gore, the wife of politician Al Gore, heard her 11-year-old daughter listening to Prince's "Darling Nikki," which references female masturbation. Susan Baker, the wife of the White House chief of staff, had a similar revelation when she heard her 7-year-old daughter singing Madonna's "Like a Virgin."

The concerned mothers formed a group called the Parents Music Resource Center (PMRC) and started a moral campaign, contacting the Record Industry Association of America (RIAA) seeking censorship of music they deemed objectionable and harmful to children. The RIAA initially shot the attempts down, citing the First Amendment. Eventually, they agreed to consider adding a warning label to albums that contained explicit songs, and the movement escalated to a 1985 Senate hearing.

At the hearing, the PMRC presented a list of unacceptable songs they deemed the "Filthy 15." Standing in defense of freedom of speech were an unlikely trio of musical artists: John Denver, Frank Zappa, and Dee Snider. According to Rolling Stone, Denver likened such censorship to the Nazi book burnings, and Zappa called the committee "the wives of Big Brother" (via American Journal of Criminal Justice). Oddly enough, Snider, the frontman of Twisted Sister gave the most eloquent testimony. Introducing himself as a drug-free Christian father, he explained to the Senate that song lyrics were subjective, proclaiming, "There is no authority who has the right or the necessary insight to make these judgments" (per Business Insider). Nonetheless, the Parental Advisory Label was approved and went into effect in 1990.

One-hit wonders were mass-produced and then thrown away

A measly 10% of albums released each year turn a profit, as per the RIAA (via PBS). To offset such large losses, record labels churned out as many songs as possible, hoping that a few would become hits. In his book "The Billboard Book of Gold and Platinum Records," Adam White points out that the RIAA also introduced the cassette single in 1987 and lowered the certification sales criteria so more hit singles could be classified as gold or platinum. This created excitement and shifted the listener's focus to the single, a trend that continues today.

According to Harold L. Vogel in "Entertainment Industry Economics," labels focused on finding many new acts as the upfront costs were much lower. Once the label found a hit, there was little incentive to keep investing in the artist unless they could immediately replicate the experience. Thus, a culture of mass-producing one-hit wonders was born.

Consider the career of Madonna. In 1982, her first deal with Warner Brothers Records was based purely on singles and was not a full contract. According to Refinery29, she was simply offered an advance of $15,000 per single. Luckily, it worked out for her, but the same cannot be said of most '80s acts, who had one big song and then faded away. In a list VH1 compiled of the "100 Greatest One-Hit Wonders of the 1980s" (via EW), you will find the likes of "Come on Eileen" by Dexy's Midnight Runners, "The Safety Dance" by Men Without Hats, and "I Melt With You" by Modern English –- songs that defined the '80s and are still loved today, but whose creators became carnage in the decade's excess.