The Controversy Over The Benin Bronzes Explained

Repatriation is finally reaching a place in the modern world where pieces of cultural significance are making their way back to the cultures they are particularly significant in — but there's still a long way to go. Curiously enough, the idea of repatriation goes all the way back to Napoleon and his invasion of Egypt, according to Project Archaeology. Granted, the act of taking art and artifacts from other cultures goes back even further than that, but the act of actually returning them is much newer, though it still has a few centuries of history.

The whole idea of repatriation takes on a whole new light when you factor in colonialism and the horrors it brought, especially in Africa, which has been suffering from the ripple effects of the institution of slavery for centuries. Accompanying that skid mark on history is the loss of significant historical and cultural artifacts that have since spread across the globe to museums in all the major centers of humanity.

However, among all the "spoils" that colonials took from Africa, no singular episode has led to a more widely lost haul of artifacts than the Benin Bronzes. The controversy surrounding these pieces of art and culture has been ongoing for over two centuries and while the ending point looks like it may be creeping up on us, there is still a ways to go in seeing all these pieces back to where they belong. Let's dig into the Benin Bronzes controversy and its origins.

The origin of the Benin Bronzes

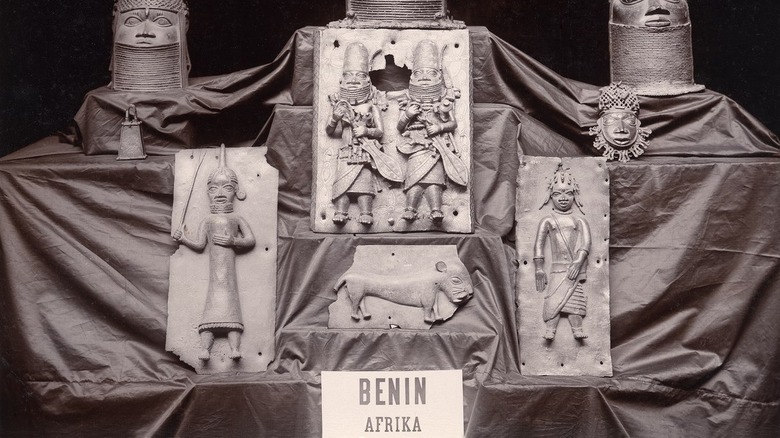

The name of the collection itself is a bit of a misnomer. In the same way that the Holy Roman Empire wasn't holy, Roman, or an empire, the Benin Bronzes aren't from Benin, nor are they made of bronze. Let's cover the Benin bit first — the pieces do actually come from Benin, just not the country of Benin. They come from the ancient Kingdom of Benin, centered around Benin City, which is now in southwest Nigeria, per The New York Times.

Then there's the matter of them not actually being bronze, but more like brass. At least the majority of them are. You see, the collection itself is pretty diverse, and includes upward of 3,000 individual pieces, perhaps even more, explains the Times — all lumped together for various reasons, including the point of origin in Benin City.

As far as what pieces are included in the collection, there are about 900 brass plaques that encompass the biggest known chunk, but there are also sculptures, commemorative heads, figures of humans and animals, royal items, and personal ornaments, according to the British Museum. They were made in the heyday of the Kingdom of Benin, starting around the 16th century by royal artisans and guilds that served the king. It's especially important to note that a lot of these pieces were specifically meant as adornments for tombs of ancestors.

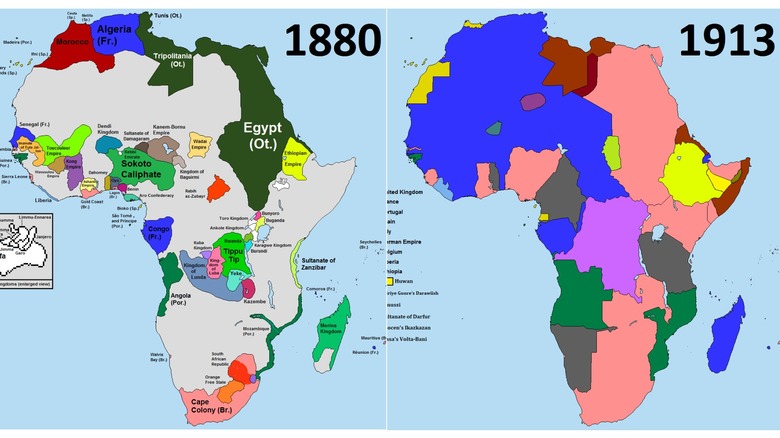

The Scramble for Africa

During the made land-grab when sea travel became more accessible to all of the major European powers, Africa got shafted pretty horribly, arguably worse than any of the other colonized continents. It was known as the "Dark Continent," because it was so unknown to the European powers, according to the University of Cambridge. In turn, this led to a particularly morbid period of history called the Scramble for Africa, also known as the Partition of Africa (via BlackPast).

If colonization wasn't bad enough on principle alone, the 1884-1885 Scramble for Africa was even more heinous, because not only did the European powers go on a mad grab for land that wasn't theirs, but they all gathered together beforehand. Thirteen European powers and the United States met at the Berlin Conference (via CNN), all chatting and drawing up the "rules" for becoming the cruel overlord of a continent already ripe with its own cultures and civilizations, many of which were doing rather well for themselves already.

There are plenty of horrific examples across the continent of where this went horribly for the African tribes and their homes. The French took up a massive patch of northwestern Africa, with the British situated just to their east, but the Kingdom of Benin itself, nestled around the Gulf of Guinea, also fell under British control, per the British Museum, and as most British-controlled colonies went, it didn't take long for it to get bloody.

The impact of the slave trade

Similar to ongoing racial discussions in America and across the globe, just because slavery is no longer an institution doesn't mean there aren't still ripple effects from its prevalence throughout past centuries. Nowhere was and is that better seen than in the destabilization of Africa at the time that the scramble occurred. When the European powers were coming to Africa, slavery had already largely been abolished, but the effects left a lot of African tribes in a state of disarray.

According to Britannica, while the slave trade was actively lining the pockets of slave traders with gold, the economic benefits that African tribal leaders received for providing slaves left Africa in a destabilized, violent state. Residual depopulation continued to ensure that tribes weren't as capable of defending themselves from foreign incursion, as well as limiting any given tribe's ability to establish consistent agriculture. And since European slavers usually left behind the old or decrepit, most tribes suffered doubly trying to support a population that struggled to support itself.

History notes that 12.5 million Africans were displaced during the transatlantic slave trade from the 16th to 19th century. Take that many people out of any society in any stage of growth and it's going to be crippled for generations. That's what allowed the European powers to gobble up African land and culture relatively unchecked.

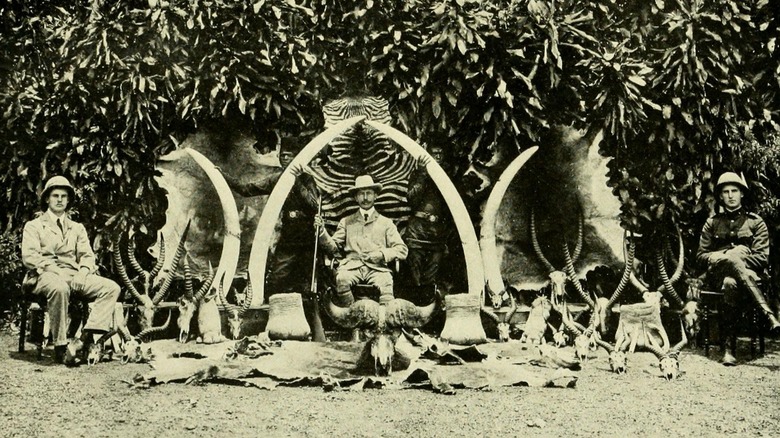

Bloody colonialism

Even with slavery abolished, the effect of colonialism on the African continent came hot and heavy with the arrival of more European powers, this time not to steal the people of Africa, but to steal the land instead. Not surprisingly, this also had a debilitating effect on an already debilitated African ecosystem. Since Europeans were treating the continent like they had treated America, they expected the African tribes to assimilate into European culture and, in the process, stomped out all remnants of native art and tradition, per Britannica.

Another problem that led to further damage on the African continent has even more parallels to what happened in America. In America, the Spanish, British, and French had used Native American tribes against each other in their own inter-colonial conflicts, and the same was seen throughout Africa. Rivalries sprung up all over, French vs. British, German vs. Belgium, and so on. And you can guess who got pulled into it, whether they liked it or not — the various African tribes and civilizations.

Britannica points out that the entire societal structure throughout the African continent practically crumbled underneath colonialism and its mobile governments as they enforced their own political and economic rule. Essentially, while the African peoples were trying to grow their own culture, they now had unfettered French and British overlords engaging in an Anglo-French rivalry (via the BBC) to take more of their stuff and use it for their own gain. Which is not a fruitful place for culture to spring up and thrive.

The 1897 clash with Benin City

In the late 19th century, as the Scramble for Africa began to define the borders of colonial interests, the Nigerian coast fell into the hands of the British, according to the British Museum. Whatever sovereignty African tribes had in the earlier part of the 1800s was quickly slipping away to the colonial powers who had no problem phoning home for reinforcements. The tribes, however, were caught in a long game that they were always destined to lose.

That said, when it first began, even the colonial powers wanted to play by the rules as much as they could, while still getting away with all they could in the meantime. Around Benin City, the British didn't like the rules of the game that the Kingdom of Benin put up around trade, and naturally, that meant that the British were looking for a means of exploiting the system to benefit them more. This tug of war, per National Geographic, led to friction between British colonists and the Kingdom of Benin.

In 1897, the British sent a "trade" convoy to Benin City, though it was clearly meant to provoke an attack. It did. The Kingdom of Benin attacked the convoy, and just like that, the British had their excuse to move in. Rather than attempt negotiations, the British drew up a large-scale military invasion and enacted it, destroying massive portions of Benin City, including the royal process, and raiding the Kingdom of what are now known as the Benin Bronzes (via the British Museum).

Changing of hands

The "spoils of war" that the British claimed from Benin City included all the Benin Bronzes (including the 900 brass plaques that decorated the palace walls and provided historical record), ivory tusks, ancestral decorations, commemorative heads, and pretty much anything with any monetary value, which also translated to anything with cultural significance to the people and society of the Kingdom of Benin, according to the British Museum.

While the British kept a large portion of the haul, including the 900 historical brass plaques currently on display at the British Museum, the basis of a market economy is to sell for a profit, and the British invaders did just that, selling off chunks of the collection to the highest bidder, which has led to the Benin Bronzes ending up scattered across the world.

AuctionDaily recounts the uptick in interest in "tribal arts" around the 1950s, which led to a burst in sales of the Benin Bronzes, which made millions of dollars for the colonial powers that had seized them. Sotheby's sold a commemorative head for $4.7 million as recently as 2007, but the scattering of items to private and public collections had been going on for the majority of the 20th century. And while most are accounted for in various collections, some still make their way into auctions, much to the ire of practically everyone who doesn't stand to financially benefit from its sale.

As it stands, pieces of the Benin Bronzes have passed through and remain in countless countries, from Germany to the United States, and beyond.

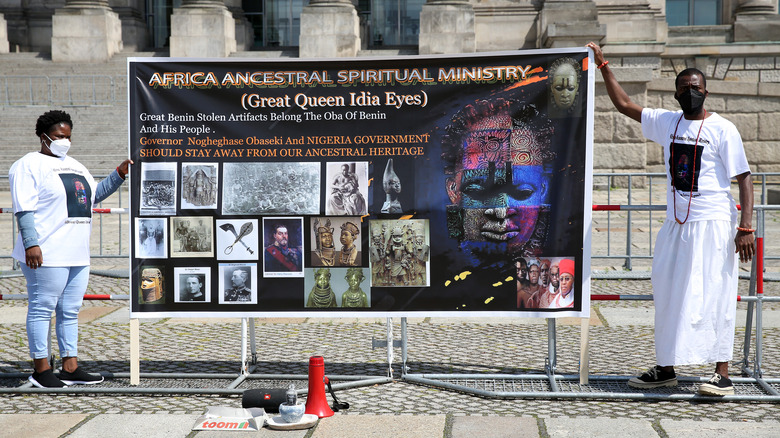

The 2021 request

Having gone centuries without historical records and cultural objects vital to their societal growth, it wasn't until October of 2021 that Nigeria made an official request to the British Museum for the safe return of all the Benin Bronzes currently on display in the museum's halls. This included the famous 900 brass plaques that previously hung proudly in the royal palace of Benin City. The letter came from Nigeria's Federal Ministry of Information and Culture.

While this is the first official request that Nigeria has made, representatives of the Benin Royal Palace had already been openly speaking about the need to repatriate the artifacts that had been previously stolen from them, per the British Museum. There have also been ongoing conversations with the Benin Dialogue Group, established to keep communications clear between Nigeria's cultural representatives and the various institutions that still house stolen artifacts from the 1897 raid (via the University of Cambridge). The Benin Dialogue Group remains in open discussions to establish museums in Benin City that can house the artifacts that Nigeria's request called for.

Back in 2018, the British Museum's director visited the king of Nigeria for in-person discussions, and while the king continuously requested the return of the stolen objects, it led to further controversy culminating in the 2021 letter for restitution.

The first museums commit to repatriation

While discussions are ongoing, breakthroughs as recently as 2021 have been pretty numerous across various museums in an effort to return objects stolen from the Kingdom of Benin to their rightful place in Benin City. Germany was responsible for a massive agreement with Nigeria in April of 2021 that would see around 1,100 Benin artifacts scattered across 25 museums returned to the country of origin, according to The Art Newspaper.

Not long after that, the Museums Association released a sizable list of museums around the English Isles that still housed various pieces of art and history from the looting of Benin City. Some institutions, like the National Museum of Ireland, returned 21 objects. Some, however, are still waiting for claims to be made. The Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at Cambridge, for instance, houses around 136 Benin artifacts. They waited for a claim to be made and are now in the process of determining how to act on the claim and return the items to Benin (via the University of Cambridge).

Many museums like the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology at Cambridge continue to state their support for repatriation; they are just standing by as discussions are ongoing as how far as how best to ensure the safety and keeping of all these significant objects.

The Smithsonian controversy

While Germany's massive contribution was a big step forward, and the smaller institutions returning the objects unconditionally helps, bigger steps are still waiting to be taken from institutions like the British Museum, which is still actively discussing the return of the 900 brass plaques. Very recently, however, another controversy seemed to have ended on June 13, 2022, when the Smithsonian pledged to return 29 of its 39 artifacts obtained from the 1897 raid on Benin City.

The controversy escalated when Ngaire Blankenberg, the director of the Smithsonian's National Museum of African Art, removed the objects from their display, according to The Washington Post. Blankenberg told the Post that he "wanted to make sure that negative reaction wasn't being felt by anyone else." The Smithsonian had just completed an evaluation of all its pieces, determining which they could display, and which belonged elsewhere and should be returned. This evaluation is meant to determine how each piece was obtained and to address and wrongs that had been committed.

While the Smithsonian committed to this overdue act, the fact remains that it is only returning a portion of the Benin artifacts to Benin City, keeping hold of a separate 10. While the reasons for the decision are unclear, it isn't all that unlikely that if the 10 artifacts were obtained around the 1897 raid, the temperature around the pieces could rise yet again.

Establishing museums in Benin

Most museums are at a place now where, even if they wanted to keep hold of these objects of rich cultural significance, they just couldn't. The public won't stand for it, and before long, it's highly probable that all identified pieces of the Benin Bronzes will be repatriated back to Benin City.

That said, if there is a holdout, one reason museums can give for not returning their Benin objects just yet centers around Benin City opening a museum that can properly house and care for those objects, according to the British Museum. After all, say what you will about various museums in England and the United States, but they certainly take care of their artifacts.

While the Nigerian National Commission for Museums and Monuments remains in charge of the requisition of these lost pieces and the new Edo Museum of West African Art in Benin City continues its construction (for a planned opening in 2025, per ARTnews), the clock's ticking on the tensions surrounding the yet-to-be-returned Benin Bronzes. While many museums have pledged to send pieces back, most won't make the journey until the latter portion of 2022, and when places like the British Museum finally commit to returning its pieces as well, it will likely take even more time to ensure safe transit.

The pieces are in place to ensure that everything is set right after centuries of wrongs. Now it's just a matter of time to see it all through to completion.