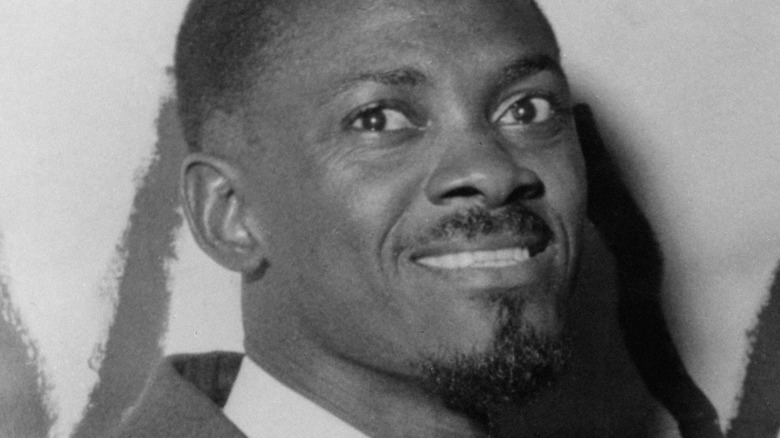

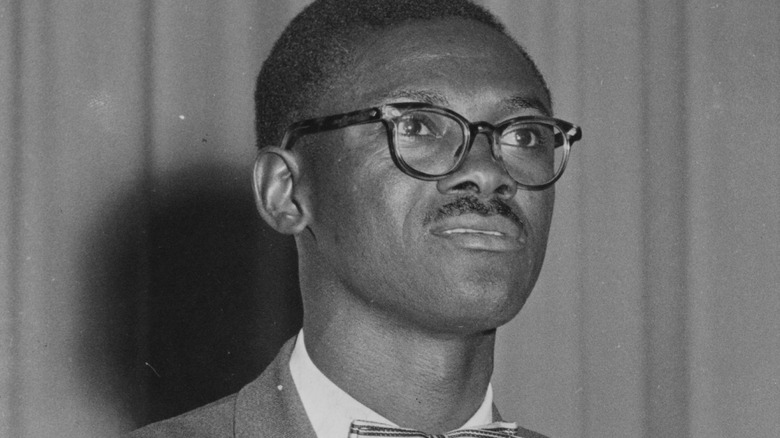

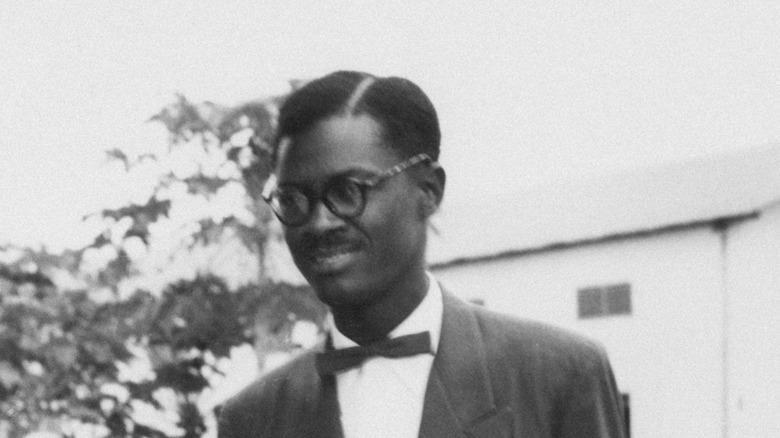

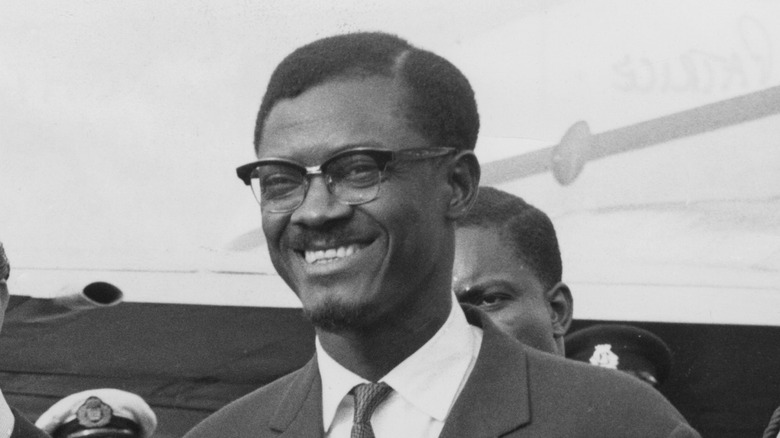

The Tragic True Story Of Patrice Lumumba

In 2022, 61 years after his death, the only known remaining body part of Patrice Lumumba was finally laid to rest. The first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Lumumba was a staunch anti-colonialist whose visions of Congo's decolonization put him in the crosshairs of the CIA.

The Guardian calls Lumumba's murder "the most important assassination of the 20th century," and considering how many assassinations there were in the 20th century, the magnitude of that statement becomes clear. But the CIA wasn't the only one who wanted to eliminate Lumumba's influence. Belgian authorities had been trying to stifle and silence Lumumba since his early political days. Not to mention the internal enemies and rivals in Lumumba's own circles. And the United Nations doesn't have clean hands either.

Some argue that Lumumba's assassination ultimately galvanized a generation of student activists. The Conversation writes that "the murder opened the eyes of many to the violence of neocolonialism." And in response, student activists in the 1960s pushed for decolonization and pushed for pan-African unity, continuing Lumumba's vision. Ultimately, it's impossible to say what would've happened in the Democratic Republic of the Congo had Lumumba stayed alive and remained prime minister. But one thing is for certain; Lumumba's death was the result of two colonial powers who were determined to stifle an anti-colonial movement. This is the tragic true story of Patrice Lumumba.

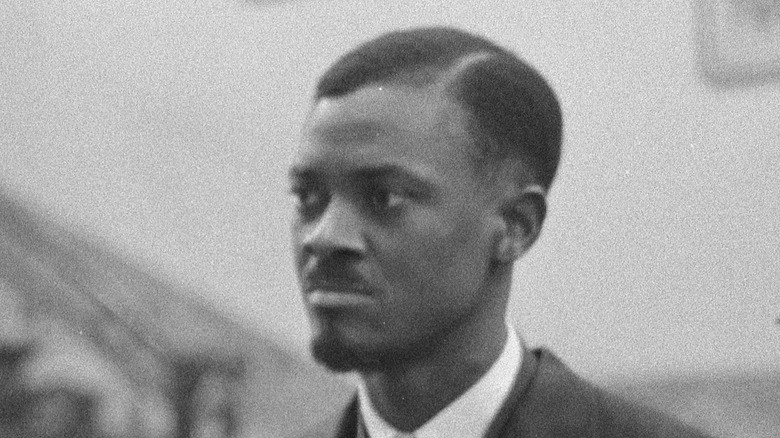

The early life of Patrice Lumumba

Patrice Émery Lumumba was born Elias Okit'Asombo on July 2, 1925, to a Batetela peasant family in a village in Onalua in the Belgian Congo, now known as the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). Initially, he was educated by his parents, Francois Tolenga Otetshima and Julienne Wamato Lomendja, but he was soon enrolled into a Catholic school and moved to a Protestant mission school by the age of 13. According to "Postcolonial Agency in African and Diasporic Literature and Film" by Lokangaka Losambe, the homestead education taught Lumumba communal values while "the assimilationist Catholic education exposed him to exclusive colonial strictures."

According to Face2FaceAfrica, even as a young child, Lumumba was already rebelling against the hierarchical status quo. He reportedly clashed with his teachers "on several occasions concerning issues bothering around his relentless steadfastness to his personal principles and values, the ultimate of which spelt; 'Justice for All.'" Lumumba would repeatedly question his parents as to why the Belgian clergy claimed to advocate for justice and equality when they oppressed the Congolese people.

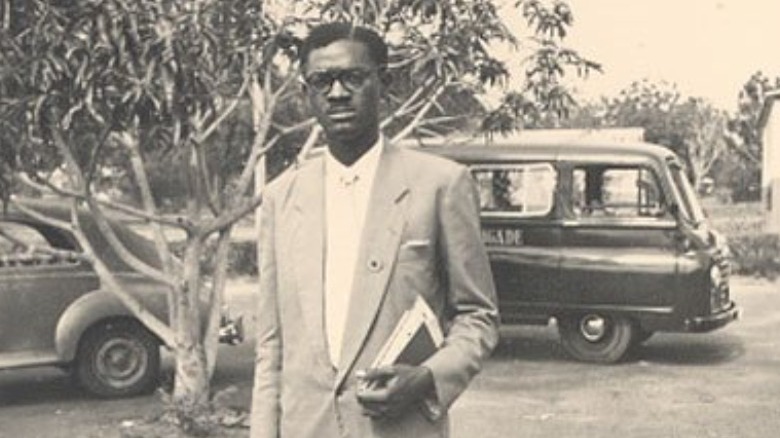

The AAREG writes that after finishing school, Lumumba briefly worked as a traveling beer salesman in Léopoldville, now known as Kinshasa, and as a postal clerk in Stanleyville, now known as Kisangani. But by the 1950s, Lumumba started to get involved in the political scene of the Belgian Congo.

Trumped-up charges

In 1955, Patrice Lumumba dipped his toes in both politics and the labor movement. In addition to joining the Belgian Liberal Party in 1955, Pambazuka News writes that Lumumba also became regional president of an all-Congolese trade union of government employees. And "unlike other unions in the country, [this trade union] was not affiliated to any Belgian trade union"

During this time, Lumumba also began working as a journalist, writing for La Voix du Congolais, Vois du Conlais, La Croix du Congo, and L'Afrique et le Mond. According to "Time and Thoughts of African Political Thinkers," edited by Godfrey O. Ozumba & Elijah Okon John, Lumumba's early writings "emphasized problems of racial, social, and economic discrimination."

But Belgium and its Colonies explains that Lumumba's anti-colonial writings caught the attention of Belgian officials. And after being invited for a study tour of Belgium in 1956, in an effort to redirect his attention, Lumumba was ultimately arrested upon his return the following year "on trumped-up charges of embezzlement" from the post office. According to "Africa: A Modern History," by Guy Arnold, Lumumba claimed that he "had only taken the responsibility for thefts by his staff, but the authorities were determined to get him out of the way." After his arrest and conviction, Lumumba was initially sentenced to two years in prison. However, the Minister for the Colonies reduced his sentence to one year.

Arrested for being anti-colonial

After Patrice Lumumba got out of prison, he became even more involved in politics. Belgium and its Colonies writes that he also became known for being one of the anti-colonial activists that sent a letter to the Governor-General of the Belgian Congo, "demanding independence and African participation in governance."

In October 1958, Lumumba founded the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC), or the Congolese National Movement, and also went on to attend the first All-African People's Conference in Accra, Ghana, put together by George Padmore and Kwame Nkrumah. The Review of African Political Economy writes that Lumumba was especially inspired after the conference to push for the decolonization of the Congo.

According to Tribune Magazine, Lumumba demanded a date for Congolese independence from Belgian authorities in March 1959. Working to promote Congolese independence, Lumumba was subsequently arrested a second time in November 1959. During a speech to the MNC congress, Lumumba called for a nationwide campaign of civil disobedience against Belgian colonial rule and was subsequently arrested for the resulting protest. In January 1960, Lumumba was held responsible for the protest and sentenced to six months' imprisonment, according to "African Political Thought" by G. Martin.

Advocating for independence

Despite being sentenced and imprisoned, Patrice Lumumba served only a few days of his sentence before being released to attend the Belgian-Congolese Round Table Conference in Brussels, Belgium, in January-February 1960 to discuss Congo's independence. According to "City Politics" by J.S. La Fontaine, the MNC reportedly made it clear that if Lumumba wasn't present, they wouldn't participate in discussions. And even Belgium authorities realized that the conference would be a failure if Lumumba wasn't present, writes "Africa: A Modern History," so he was released from prison in order to attend the conference.

During the conference, it was decided that the first national elections would be held in May 1960, and the date for Congo's independence was set for June 30, 1960. And one month before the DRC was set to be independent, the MNC won the national elections. After forming a coalition, Lumumba became the first prime minister of the DRC.

According to "Cold War in the Congo" by Frank Villafana, Belgian officials reportedly tried "various ploys to prevent Lumumba from forming a coalition and taking power, but they were ultimately unsuccessful."

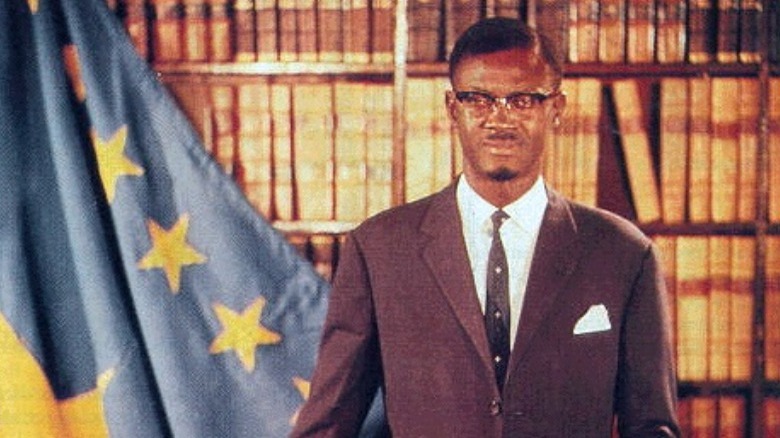

The first prime minister of the DRC

Patrice Lumumba formed the new government of the DRC on June 23, 1960, and the new government took office on June 30, with Lumumba as Prime Minister, Joseph Kasavubu as the President of the DRC, and Joseph Mobutu as the Secretary of State for Defense.

Several people spoke on the first independence day, including King Baudouin of Belgium, who praised colonialism and the actions of his great-granduncle, King Leopold II of Belgium. According to "Africa: A Modern History," Lumumba hadn't even been scheduled to speak, but after hearing King Baudouin's speech, he went up to the podium.

Speaking in response to King Baudouin's speech, Lumumba stated that "we are proud of this struggle, of tears, of fire, and of blood, to the depth of our being, for it was a noble and just struggle, and indispensable to put an end to the humiliating slavery which was imposed upon us by force," per "Times and Thoughts of African Political Thinkers," edited by Godfrey O. Ozumba and Elijah O. John. One of Lumumba's most famous quotes also came from this speech, in which he stated directly to the king of Belgium, "We are no longer your monkeys."

Secession in Katanga and Southern Kasai

Immediately after becoming prime minister, Patrice Lumumba was faced with two secessionist movements in Katanga and South Kasai. Encouraged by the Belgians and the mining conglomerate Union Minière du Haut-Katanga (UMHK), the Katanga Province seceded from the DRC under the theoretical leadership of Moïse Tshombe on July 11, 1960, Philip Thody writes in "Europe Since 1945." Belgium reportedly planted the seeds for Katanga's secession in 1958, motivated by the fact that nearly 50% of the Congo's tax revenue came from Katanga, which held large deposits of numerous minerals, Charles G. Thomas and Toyin Falola write in "Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa," Karavubu and Lumumba asked the United States for aid, but they were rejected by President Eisenhower, who told them to ask the United Nations instead.

Although the United Nations agreed to send troops, they refused to suppress the rebellion, leading Lumumba to request aid from the Soviet Union, according to "Times and Thoughts of African Political Thinkers."

In addition, South Kasai had declared independence on June 14, 1960, a little over two weeks before the DRC's own independence day. In an attempt to end the secession, Godfrey Mwakikagile writes that Lumumba sent troops, led by Mobutu, to South Kasai, resulting in a massacre. The province was ultimately retaken by the DRC in December 1961.

Put under house arrest

Believing that Patrice Lumumba was a political liability, especially following the massacre in South Kasai, President Kasavubu dismissed Lumumba from his post. In response, Lumumba declared that as prime minister, he was one the deposing Kasabuvu from the presidency, according to "Decolonization and Regional Geopolitics" by Lazlo Passemiers. In response to this power struggle, Mobutu orchestrated a coup d'état on September 14, 1960, and declared that Congolese politics were to be suspended for six months while the College of Commissioners-General took over. Kasabuvu was left ceremoniously in power, while Lumumba was subsequently put under house arrest.

According to "The Assassination of Lumumba" by Ludo De Witte, Lumumba went out freely in public for the last time on October 9, 1960. The next day, Mobutu ordered soldiers to surround his house. There, Lumumba was immobilized and cut off from his power base, "guarded by Congolese soldiers who in turn were monitored by Ghanian, Moroccan, and Tunisian UN Troops." UN leaders also told Lumumba that they would only protect him if he remained effectively under house arrest; "in short, Lumumba could only count on protection as long as he was inactive politically."

"Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa" writes that in December 1960, Lumumba managed to escape from house arrest and get to Stanleyville, where most of his political followers were. However, he was soon recaptured and held by the Congolese central government.

Dissolved in acid

Despite having recaptured Patrice Lumumba, he was considered too dangerous to keep imprisoned. According to "Secession and Separatist Conflicts in Postcolonial Africa," "already his political followers in the Stanleyville region were arming themselves and could likely threaten the Leopoldville government." Because of this, Lumumba was flown to Katanga, along with two of his associates, Youth and Sports Minister Maurice Mpolo and Senate Vice-president Joseph Okito, where they were tortured and beaten.

"Times and Thoughts of African Political Thinkers" writes that during the last week of his life, Lumumba was "dragged around with a rope around his neck, while his captors yanked his head for the benefit of newsreel cameras."

On January 17, 1961, Lumumba, Mpolo, and Okito were driven almost 50 miles outside of Elisabethville. There, they were executed by firing squad and buried in a shallow grave, according to "Decolonization and Regional Geopolitics." The bodies were only briefly left buried and, before long, were disinterred and dissolved in acid to destroy any trace of the bodies and to prevent the grave from becoming a pilgrimage site, reports CBS News. Although rumors of Lumumba's assassination leaked, Nigel Cawthorne writes in "Assassinations That Changed The World" that the official announcement regarding Lumumba's death was that he had "escaped and been murdered by hostile villagers."

A United States-sponsored coup

Although Patrice Lumumba's assassination was claimed to be the result of an internal power struggle in the DRC, both the coup and his assassination were part of a CIA-sponsored plot. But the CIA didn't work alone. The Africa I Know writes that the CIA worked with the British, Belgian officials — who had their own assassination plot — and Lumumba's Congolese political rivals like Mbutu and Tshombe.

In "Memories of Violence in Peru and the Congo," Gilbert Shang Ndi writes that "it is well established that Belgian officials and CIA officials on the ground connived with the local arch-enemies of Lumumba in eliminating him." Declassified UK also writes that British officials did all they could to encourage Lumumba's enemies to execute him. And there's little doubt that Daphne Park, MI6 station chief in the DRC under cover of consul at the British embassy, was well aware of the CIA's plot.

By the time Lumumba was assassinated, the CIA had already tried to poison him several times. And according to "Colonial Mentality in Africa" by Michael Nkuzi Nnam, he became a CIA target when he appealed to the Soviet Union for aid, at which point CIA director Allen Dulles wrote, "consequently, we conclude that his removal must be urgent and prime objective." Dulles even described Lumumba as "a Castro, or worse," per The New York Times Magazine. Meanwhile, Lumumba never called himself a communist or a socialist and was a self-described African nationalist.

Belgium acknowledges responsibility

On February 5, 2002, Belgium finally issued an apology for its role in Patrice Lumumba's assassination, 41 years after his murder. The Guardian reports that although Belgian authorities may not have pulled the trigger themselves, they "failed to protect Lumumba even though it knew he was in mortal danger, lent its military expertise and personnel to those who would murder him, and then did its best to cover up what had happened." Foreign Minister Louis Michel stated that "some members of the government, and some Belgian actors at the time, bear an irrefutable part of the responsibility for the events that led to Patrice Lumumba's death" and announced that a $3.25 million fund was to be created in Lumumba's name "to promote democracy in Congo," per The New York Times.

Although the Belgian parliamentary inquiry determined that Belgium had a moral responsibility for the killings and that they were backed by the CIA, the CIA has repeatedly denied any responsibility for Lumumba's assassination.

In "The Assassination of Lumumba," De Witte writes that through the Belgian parliamentary inquiry, more information about Belgium's role in the destabilization of the Congo was made public. In addition to the secret funds used to overthrow the Congolese government, the inquiry revealed that the Belgian king was reportedly kept informed of the assassination plots against Lumumba.

Returning his tooth

While Patrice Lumumba's body was dissolved in acid, Belgian policemen Gerard Soete walked away with two teeth from Lumumba's body, purportedly as a sadistic trophy. The Guardian reports that Soete admitted to keeping the teeth on Belgian TV in 2000, but after repeated calls for their return back to the DRC, Soete claimed that he had actually thrown the teeth into the North Sea. But over 15 years after his death, Soete's own daughter accidentally revealed his deception. According to the BBC, when Soete's daughter Godelieve gave an interview to the Belgian magazine Humo in 2016, she revealed that she was able to save some things after her father's death, including the tooth of Lumumba.

France24 writes that the tooth was seized when Lumumba's family filed a complaint after hearing about the tooth. However, AfricaNews reports that "only one tooth attributed to Lumumba was recovered by the federal prosecutor's office." And after a 4-year battle in the Belgian courts, it was finally ruled that the tooth should be returned to the Lumumba family.

On June 20, 2022, Lumumba's tooth was finally returned to his family in the DRC. Three days of national mourning were held before the funeral, and on June 30, 2022, the 62nd anniversary of the DRC's independence and 61 years after his murder, Al Jazeera reports Lumumba was finally buried.