Booker T Washington And George Washington Carver Had A Complicated Partnership

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

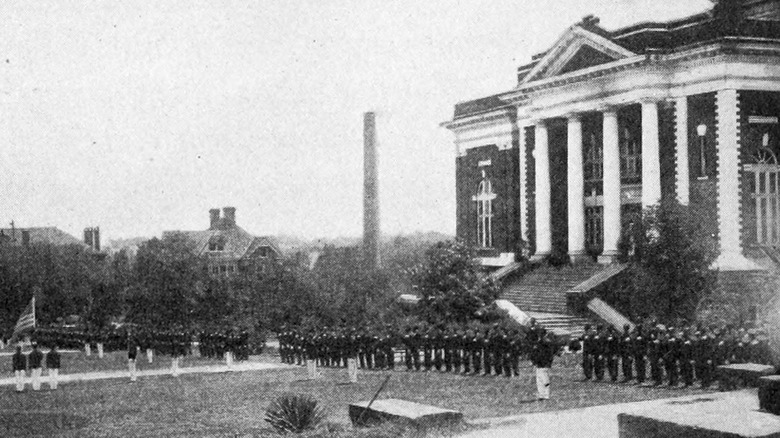

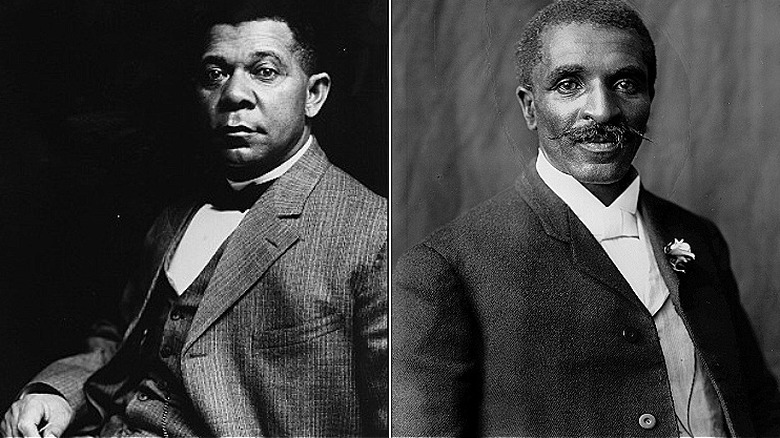

In the late 1800s, a young former slave named Booker T. Washington walked 500 miles to get an education, according to Biography. He'd grow up to share that education, founding the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute — the all-Black college, and the first-ever of its kind. Washington is remembered as the "Father of Negro Education," as well as a famous, and somewhat controversial, Black orator, was respected by white presidents and honored publicly by one, as Samford Univerity notes. Eventually, there would be a national monument erected in his name.

Another former slave who'd struggled for an education was George Washington Carver. George earned his fame in the 1920s for his ideas about peanuts (via Biography). He, too, was an educator, and not just any educator: He was the "Black Leonardo," according to Time. George was a prominent botanist who wanted to empower former slaves with new farming techniques, a task he worked towards all his life. He was also awarded a national monument.

The Black Leonardo and the Father of Negro Education worked together for over 19 years. They idolized each other but they also couldn't stand each other.

The beginning of a bitter rivalry, decades-long feud, & admiring partnership

It had been a year since Booker T. Washington made his big break with a famous speech before a white audience in Atlanta, Georgia, and he was on his way to deliver another one at Harvard University. It had been 15 years since he founded the Tuskegee Institute in 1881 (via Samford University), and he knew he was the boss in every way. That's when, in April 1896, George Washington Carver had received a letter from the "Father of Negro Education" himself — and a job offer along with it.

Content with his teaching post at Iowa Agricultural College, Carver initially rejected the offer. Still, Washington had continued to court Carver, promising him a salary of $1,000 (per Christine Vella's "George Washington Carver: A Life") and his own apartment. Most importantly to Carver, Washington promised him the laboratory and all the supplies he needed to pursue his work in agricultural science. All George had to do was go to Tuskegee.

Booker T. Washington seduces a young George Carver, then whisks him away to Tuskegee

George Washington Carver still hesitated to accept Booker T. Washington's offer — Carver was happy at his teaching job in Iowa. He found himself drawn to Washington, the Black near-celebrity whose dreams were so similar to his own. He agreed to meet with Washington in Cedar Rapids.

Immediately upon meeting him, Carver was intoxicated by Washington's magnetism (via NBC). Washington spoke with passion, and promised Carver the moon. They both wanted to empower Black communities: Washington through education, Carver through farming. "[Washington] drew idealists like Carver to him," said Christine Vella (via "George Washington Carver: A Life"), adding, "After their conversation, George never again thought seriously of going anywhere but Tuskegee."

"Providence permitting, I will be there in November," Carver wrote to Washington after the two parted ways. He inquired about plant samples but Washington did not reply. Nonetheless, a wide-eyed and idealistic Carver arrived at Tuskegee in November 1896 to begin his life-long work at Tuskegee under the watchful eye of Washington.

Booker T. Washington was 'gnawed with jealousy'

George Washington Carver soon discovered that the lionized "Father of Negro Education" was not the warm, fatherly type when it came to staff management.The NPS History Archive notes: "Booker T. Washington was the great guiding force at Tuskegee ... His ability and determination in the face of the greatest obstacles were an inspiration to all those associated with him. At the same time, Washington's exacting, demanding manner made him difficult to work for."

Carver and Washington had conflicting work styles and their personalities often clashed. Washington was a meticulous manager who was "gnawed by jealousy of his erudite professor," as Christina Vella writes for NBC. Carver, for his part, felt stifled by Booker's demands and asked for more than other staff members received. Washington was irritated by Carver who did not understand his employee's way of working. The two admired each other, yet were always at odds.

George Washington Carver was kind of a 'diva'

The difficulties that Booker T. Washington underwent in establishing Tuskegee were monumental. According to the NPS History Archive Washington wrote, "Perhaps no one who has not gone through the experience ... of trying to erect buildings and provide equipment for a school when no one knew where the money was to come from, can properly appreciate the difficulties under which we labored."

Author Peter Burchard said (via NPR ), "Carver had a tremendous amount of respect for [Washington], but it was a little like a little kid who had a great dad who never said 'I love you.'" In fact, the outlet goes on to describe Carver as a "diva."

Without seemingly realizing that the university had very little support or funding Carver wrote shortly after arriving at Tuskegee, "At present I have no room to unpack my goods ... I beg of you to give me these, and suitable ones, too, not for my sake alone but for the sake of education," (via "George Washington Carver: A Life").

In addition, Carver is reported to have avoided some boring yet crucial aspects of teaching. And, on more than one occasion he planned to quit his post at the university, despite Washington having given him "all kinds of privileges," (via NPR).

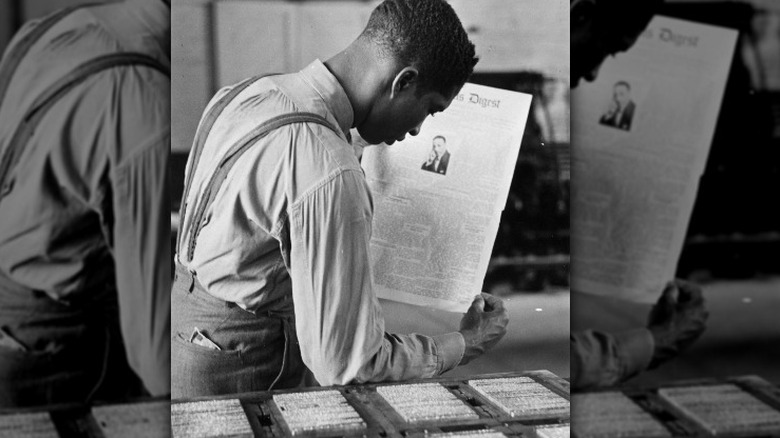

Booker T. Washington provides no supplies, but George Carver forged an independent legacy

Upon arrival at the Tuskegee, George Carver was expecting a proper laboratory, which Booker T. Washington had promised him. Instead, all he got was a room with a lamp. He had brought his own microscope with him and used the lamp to both warm his hands and as a Bunsen burner as "George Washington Carver: A Life" notes.

Alas, though, "for the entire 19 years that Carver and Washington worked together at Tuskegee, they made each other wretched," Christina Vella wrote for NBC, "Only after Booker's death in 1915 could Carver begin garnering a reputation for his scientific work."

Washington died one of the most famous men in America: a controversial figure whose impact on Black education remains unequaled in history. George Washington Carver forged himself a legacy independent from that of his former boss with his innovative ideas for farming techniques, most notably those involving peanuts, as the National Peanut Board explains.

As Washington once wrote (via NPS History Archive), "I have learned that success is to be measured not so much by the position that one has reached in life, as by the obstacles which he has overcome while trying to succeed." Washington and Carver both succeeded in changing history, even though the greatest obstacles they faced were ostensibly each other.