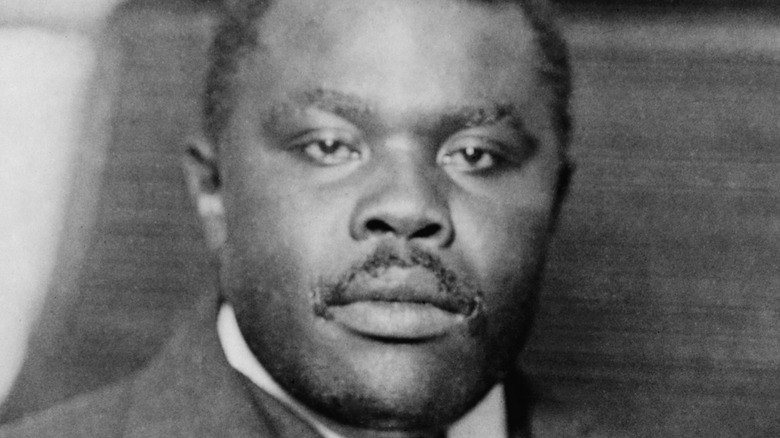

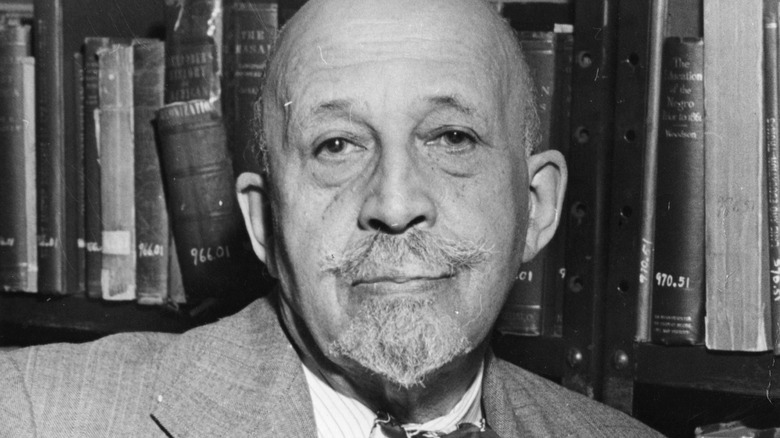

Inside The Marcus Garvey And W.E.B. Du Bois Feud

Marcus Garvey and W.E.B. Du Bois were towering Black intellectuals of the early 20th century, changing the way Americans thought both then and later.

Garvey rose to prominence after establishing the Universal Negro Improvement Association, first in his home nation of Jamaica and then in New York City after he headed to the United States for a speaking tour in 1916 (via History). The Association was dedicated to Black self-sufficiency, its secondary goal the creation of an independent Black nation in Africa (at this time, the continent was almost entirely under colonial rule by European powers). Garvey launched the Black Star Line, a shipping company he hoped would strengthen Black economic power and transport the African diaspora back to a new nation in Africa (via PBS).

W.E.B. Du Bois, born in Massachusetts and the first African American to earn a doctorate from Harvard University, helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in New York City in 1909 and became editor of The Crisis, the organization's publication, the following year (via Britannica). Through the magazine, his seminal text The Souls of Black Folk, and many other works, Du Bois castigated American racial oppression, discrimination, and violence — and their legacy. According to History, Du Bois broke new ground in the field of sociology when he studied how slavery, though abolished in the 19th century, still impacted Blacks in the South.

Though these famous leaders and thinkers had much in common, they clashed over what was possible, or desirable, in segregationist America.

The Roots of the Clash

W.E.B. Du Bois and Garvey were Pan-Africanists (via History and NAACP). They believed it was crucial for Blacks around the world to unite and cooperate in the fight for justice and decency. But their feud was rooted in what to do in the American context and whether the redemption of white society was possible.

According to NPR, Du Bois believed that the personal and professional advancements of African Americans could open the door for civil rights and acceptance. The brilliant thinkers, the masterful writers, the ingenious inventors, the educated lawyers would show white America that Blacks were deserving of the same status and rights as they. In his series of articles called "The Talented Tenth," Du Bois wrote, in the gendered language of the age, "The Talented Tenth of the Negro race must be made leaders of thought and missionaries of culture among their people. No others can do this and Negro colleges must train men for it. The Negro race, like all other races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men" (via Yale MacMillan Center).

Garvey saw little chance of acceptance, and urged Black communities to isolate and avoid contact with whites until they could return to Africa (via NPR). He rejected integration and did not shy away from talk of exclusion. He declared in a speech entitled "If You Believe the Negro Has a Soul": "Each race and each nationality is endeavoring to work out its own destiny, to the exclusion of other races and other nationalities. We hear the cry of 'England for the Englishman,' of 'France for the Frenchman'... We of the Universal Negro Improvement Association are raising the cry of 'Africa for the Africans,' those at home and those abroad. There are 400 million Africans in the world who have Negro blood coursing through their veins, and we believe that the time has come to unite..." (via History Matters).

This ideological rift boiled over — in public.

Public Attacks Escalate

The Du Bois-Garvey feud grew nasty, and widely known. Both intellectuals had powerful platforms and wide followings. While each clash had its own unique context, with plenty of other specific differences between them, the divide over racial uplift to achieve rights in the United States versus going "Back to Africa" as quickly as possible always loomed in the background.

In The Crisis, Du Bois called Garvey a "lunatic or traitor" (via PBS). Garvey called Du Bois "the white-man Negro who has never done anything yet to benefit Negroes" in a fiery speech before a full house (via Negro with a Hat: The Rise and Fall of Marcus Garvey). Du Bois, Garvey said, merely worked for the "upper tens," while he worked for ordinary people. Garvey was labeled an enemy of Blacks, while Du Bois was their "misleader" (via PBS). According to NPR, the animosity even veered toward colorism — put downs over being too dark or not dark enough. Attacks broadened from ideas to the increasingly personal.

Though the occasional olive branch was offered, the two remained bitter ideological opponents until Garvey's passing in 1940.