Tragic Details Found In American President Autopsy Reports

The autopsy isn't quite as old as human history, but it's pretty old. According to Britannica, the Greek physician Galen of Pergamum was the first person to dissect a human — not just to learn about anatomy, but to learn more about how internal things might cause external symptoms. But not every culture loved the idea of cutting up a corpse, even if it was for science. It was taboo in Roman, Chinese, and Muslim nations, and it was outright banned during the Middle Ages.

By the early 1800s, however, cutting open the deceased to have a look around was becoming a basic medical thing, and people started to understand that it could help bring closure, especially in cases where a person's cause of death wasn't otherwise known. On the other hand, medical examiners didn't really become good at their jobs until much later, and the autopsy report didn't always tell the complete story.

Autopsies were never really a given, though, even after the death of someone as important as an American president. Warren G. Harding's death, for example, was quite sudden and (according to some) kinda suspicious, but his wife refused to allow an autopsy, prompting later speculation that she might have actually poisoned him (via PBS). It's almost certainly not true, but still, autopsy reports can reveal pretty awful and tragic medical truths. Here are some of the details found in the autopsies of other American presidents.

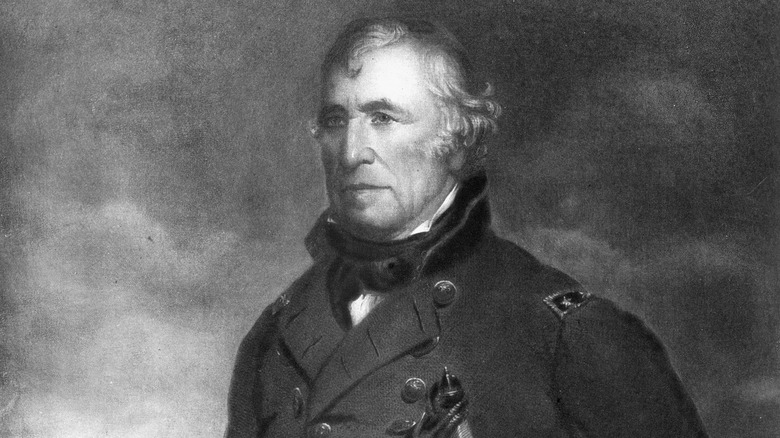

Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor was the 12th president of the United States and holds the dubious distinction of serving the third shortest presidential term in American history (William Henry Harrison gets first place, with only 31 days in office, via WorldAtlas). Taylor was in office for 16 months before he succumbed to ... cherries and milk. Or so the story goes. Taylor fell ill shortly after consuming the fruit and dairy and was sick for four days with gastroenteritis. According to History, his physicians declared he'd died of cholera.

Not everyone was convinced, and rumors that the president had been poisoned by dissenting Southern politicians persisted into the 1990s (via Politico). In 1991, those who had the authority and were sick of listening to everyone whine about Zachary Taylor had the president's body exhumed so it could undergo a genuine 20th-century autopsy.

To the dismay of everyone who loves a conspiracy, the medical examiner concluded that Taylor had definitely not been poisoned, but had died of one of "a myriad of natural diseases which could have produced the symptoms of gastroenteritis." The examiner did find trace amounts of arsenic, but not at lethal levels. The real tragedy of Taylor's autopsy report is what it says about the state of medicine during the president's lifetime. Today, acute gastroenteritis in America is an uncommon cause of death — only about .0027% of the 179 million people who get gastroenteritis each year in the United States actually die from it (via the Military Health System).

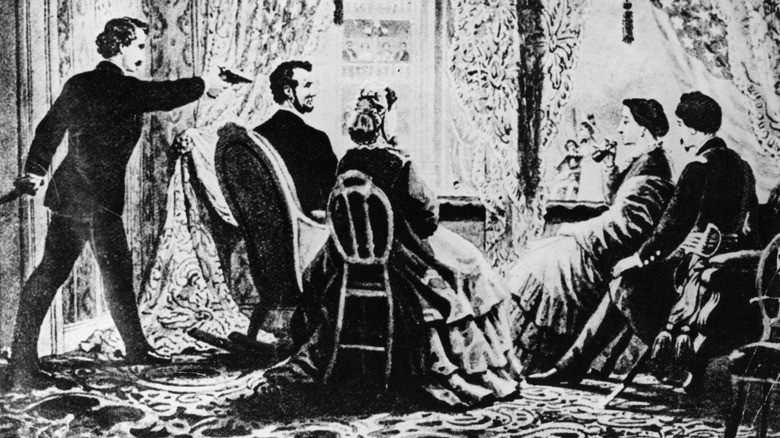

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln was the first American president to be assassinated and the first to undergo a well-publicized autopsy. To be frank, there wasn't a huge need for an autopsy since it was painfully obvious what had killed the president: The evening before, John Wilkes Booth walked into the presidential box at Ford's Theater in Washington D.C. and fired a single bullet from a Derringer pistol into Lincoln's head. He then leaped out of the booth and was foiled by none other than the American flag (or to be specific, a version of the American flag called a regimental flag), which grabbed him by the foot and flung him onto the stage, where he famously broke his leg.

Still, no one could stomach the idea of leaving a bullet in Abraham Lincoln's head, so an autopsy was ordered. According to the report (via Circulating Now), "The ball entered through the occipital bone about one inch left of the median line and just above the left lateral sinus. It then penetrated the dura mater, passed through the left posterior lobe of the cerebrum, entered the left lateral ventricle, and lodged in the white matter of the cerebrum just above the posterior portion of the left corpus striatum." Perhaps most disturbingly of all, the doctor who performed the autopsy couldn't even find the bullet until he'd removed the president's brain and the bullet fell out of it into a basin (via Smithsonian).

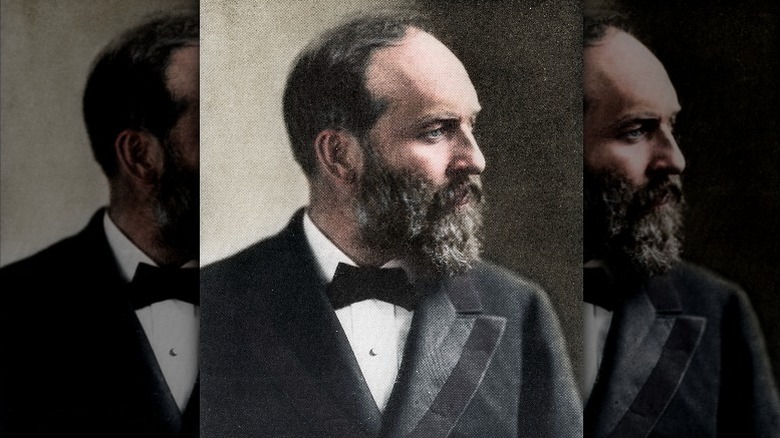

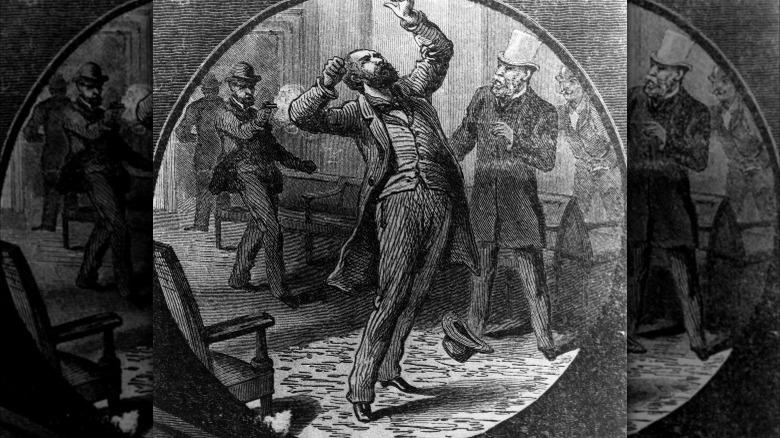

James A. Garfield

The second assassination of an American president happened just 16 years after the first. Like Lincoln, James A. Garfield was recreating (or on his way to recreating — he was in a train station) when Charles Guiteau shot him. The first bullet grazed the president's arm and the second one struck him in the back (via History). Unlike Lincoln, Garfield's wound was survivable, but germ theory wasn't really an accepted thing yet, and the good Samaritans trying to help the president in the minutes after his injury probably did more harm than good with their unwashed hands and whatever it was they were using to probe his wound.

The president lingered for more than two months. Doctors gave him quinine, morphine, and booze in an effort to "treat" him and also stuck more things into his wound in hope of retrieving the bullet. As the weeks dragged on, the president developed a persistent fever and abscesses all over his body. Then he died.

Post-mortem, doctors were finally able to locate the bullet, which had broken the president's 11th rib en route to his spinal column, where it also fractured the first lumbar vertebra and then came to rest just below his pancreas. According to the report (via The American Presidency Project), bone fragments pierced Garfield's "adjacent soft parts" and the bullet became encysted. You don't have to be a doctor to guess that leaving a bullet and bone fragments in someone's body probably doesn't put them on the fast track to good health.

Also, massive infection

If James A. Garfield's injury had occurred during the 21st century, doctors would have performed surgery right away, removing the bullet and the bone fragments (though to be fair, in some cases it isn't possible to remove a bullet). Perhaps more importantly, the surgery would have been performed in sterile conditions, limiting the chances of the kind of system-wide infection the president eventually developed.

The autopsy revealed the extent of the president's injury and subsequent decline. The bullet ruptured an artery, and Garfield's abdominal cavity had almost a pint of blood in it. There was also a 6" x 4" abscess between his liver and colon. The track the bullet left in Garfield's body was also completely infected, and he had bronchopneumonia in both lungs.

It's clear to us today what caused the massive infection. After initially failing to find the bullet, doctors spent the next weeks sticking their unwashed fingers into the wound (and the poor man didn't even receive ether to dull the pain of having his wound poked and widened). This and probably everything from the not-sterile clothes, bedsheets, and hands of everyone who touched the president led to a local infection, which slowly turned into the sepsis that prompted Garfield to cry "This pain! This pain!" in the moments before his death (via PBS).

It was obvious even to Garfield's assassin what his cause of death was — after hearing of the president's death, Charles Guiteau famously declared, "The doctors killed Garfield, I just shot him."

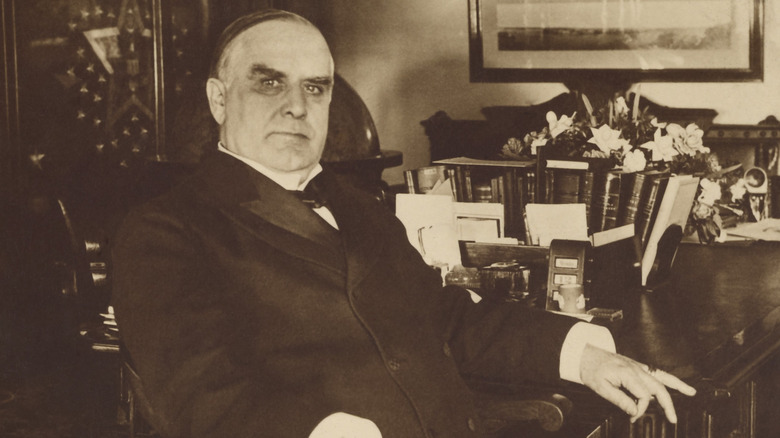

William McKinley

The third assassination of a sitting U.S. president happened on September 6, 1901, at the Pan-American Exposition in New York. The 20th century was brand-new, but doctors of the time understood a little more about how to treat a gunshot wound than they did back in poor Garfield's time.

William McKinley's medical team was headed by a gynecological surgeon, which granted is not ideal for bullet removal but it's at least safe to say the guy understood the basics of human anatomy. Still, the team was unable to find the bullet, so they basically just threw up their hands and said, "Oh well," and sewed the president back up. Happily, they at least cleaned the wound. Supposedly.

Doctors did order an X-ray machine to see if it could help them find the bullet, but evidently, they concluded the bullet was just fine where it was because they never actually used it. Instead, they told everyone the president was on the mend. He wasn't, though. He died on September 14.

At the autopsy, doctors were surprised (or maybe not surprised) to discover that McKinley didn't die from his injuries; he died from sepsis. Despite the whole "I cleaned the wound" thing, the path of the bullet was riddled with gangrene (via Visible Proofs: Forensic Views of the Body). The infection became systemic, killing him in the most unpleasant of ways. It's not an especially kind thing to say, but Lincoln sort of got the easy way out.

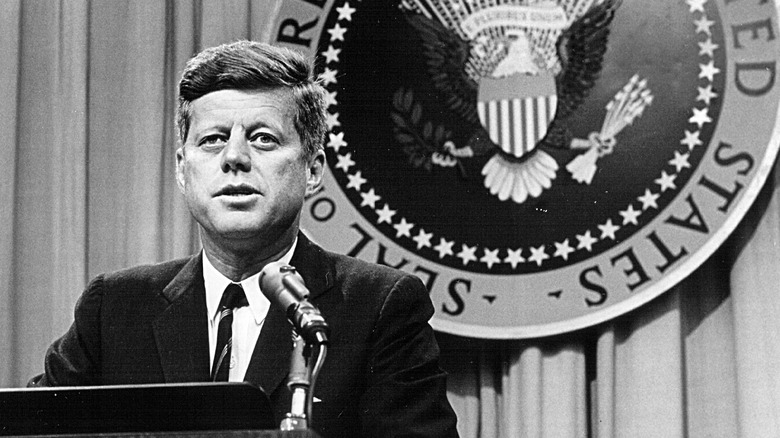

John F. Kennedy

Decades after the death of JFK, people are still arguing about who killed him and why. But the actual mechanism of his death isn't under dispute, at least not by anyone who wants to be taken seriously. John F. Kennedy, the 35th president of the United States, was killed by a bullet.

JFK had the great honor of being the very first assassinated president to undergo a thorough, detailed autopsy conducted by people who were good at their jobs and would never have dreamt of poking around in his body with unwashed hands, though at that point, it technically didn't matter. According to the autopsy report (via the National Archives), JFK was "muscular, well-developed and well nourished" and had "reddish brown and abundant" hair and blue eyes. Why those details have to be in an autopsy report is anyone's guess, but whatever.

The report then goes on to describe lots of things that weren't wrong with JFK, like old scars and teeth "in excellent repair" before finally describing the wounds that killed him. There were two of note — one was a severe head wound, the other was a bullet wound in the throat that had been enlarged into a tracheostomy by the doctor who attended Kennedy just after the shooting. To conspiracy theorists, this was a tragic detail not because of what it said about the valorous but ultimately doomed effort to save the life of someone's husband and father, but because the tracheostomy obscured the wound, thus making it impossible to know which direction the bullet had come from.

JFK's head injury

It wasn't the throat bullet that killed JFK, it was the head wound. The autopsy report says the bullet entered Kennedy's skull and fragmented; a portion of it bounced along through the cranial cavity leaving little bits of metal behind. Another portion exited through the parietal bone, which is the large part of the skull on the upper back side of the head, "carrying with it portions of cerebrum, skull, and scalp." The report then goes on to say that the force of the bullet "produced extensive fragmentation of the skull, laceration of the superior sagittal sinus, and of the right cerebral hemisphere."

The report concludes: "it is our opinion that the wound of the skull produced such extensive damage to the brain as to preclude the possibility of the deceased surviving this injury." You don't have to be a pathologist to figure that one out, but someone has to make it official.

As time goes on, there are always questions about what could have been done differently. Would Kennedy have survived his injuries if they'd happened in the 21st century rather than in 1963? An emergency physician told MedPage Today that there wouldn't have been much difference in the care Kennedy received in the 1960s and the care that would have been given to him today. The throat injury was fixable (as it was in 1963), but even cutting-edge modern medicine couldn't have increased JFK's chances of surviving the gunshot wound that tore his skull apart.

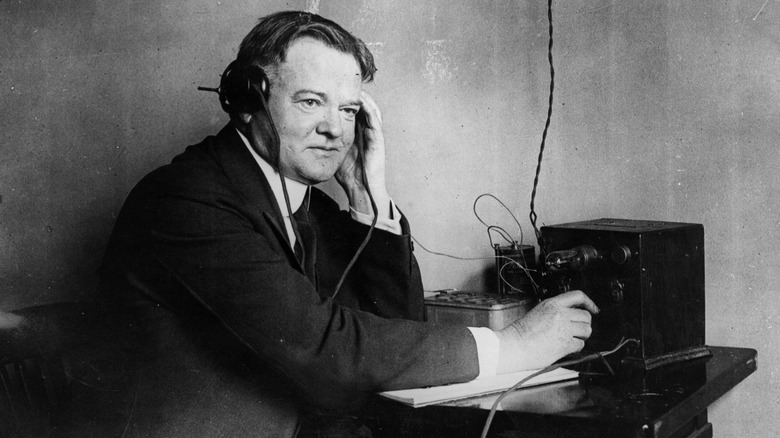

Herbert Hoover

Herbert Hoover was the 31st president of the United States, serving one term from 1929 to 1933. He is probably best known as the guy who got blamed for the Great Depression, though no one really agrees on how well-deserved that distinction is (via the White House). After his 1932 defeat by Franklin D. Roosevelt, Hoover spent most of the rest of his career being chairman of various commissions until his health finally started to decline in the early 1960s.

According to physician Michael Lepore's autobiography "The Life of the Clinician," Hoover was diagnosed with colon cancer in 1962. The primary tumor was removed and the president carried on until 1963, when he began suffering from internal bleeding. His health continued to decline throughout the following year, and in October of 1964, he died from what was described as a "hemorrhage of considerable magnitude" complicated by kidney disease.

It's hard to imagine that Hoover's death didn't have something to do with colon cancer, but that's not what the autopsy found. Medical examiners said the bleeding may have been caused by a rare vascular condition known today as Dieulafoy's lesion, which is basically just a super-sized artery in the GI tract. If doctors had known about Hoover's condition prior to his death, it's possible that prompt treatment could have saved him. But the man was 90 and repeatedly refused to be hospitalized, so not much effort was made to figure out what exactly was killing him.

Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight D. Eisenhower had suffered from high blood pressure since at least 1930 when he was a 40-year-old Army officer. In 1955, he had a massive heart attack (believed related to his high blood pressure), and later in life, he also had intermittent blood pressure spikes and four more heart attacks (via The New York Times).

He'd also had a strange episode in the middle of a cabinet meeting in November of 1957. He suddenly lost motor function — he was unable to grasp or hold papers or his pen — and observers described him as speaking "gibberish." The White House physician called his affliction an "abnormality" of the brain, though evidently, it was not so abnormal that the president wasn't able to return to work three days later, per The Philadelphia Inquirer.

After Eisenhower's death, an autopsy discovered a tumor on his adrenal gland. This type of tumor is known to cause high blood pressure, heart attack, and stroke, and could also explain why Eisenhower was so volatile that White House staff nicknamed him "the terrible-tempered Mr. Bang" (via Politico). The tumor caused a constant release of adrenaline into Eisenhower's system — this was even confirmed in 1967 when the president was prescribed a medication that blocks adrenal gland activity. For some reason, though, no one ever suspected that Eisenhower might have had a tumor, so the diagnosis wasn't made until the autopsy, when it was obviously far too late to correct his affliction.

Lyndon B. Johnson

Physician Gabe Mirkin calls Lyndon B. Johnson "one of the hardest-working presidents ever," which sounds admirable until you consider that "hard work" for Johnson meant 20-hour work days that left no time for exercise (though it's debatable if he would have exercised if he'd had the time).

Johnson also smoked, had an alcohol problem, and ate pretty much nothing but fried food, so he was not exactly a model of excellent health. Unsurprisingly, this lifestyle contributed to his first heart attack at the age of 47, a second probable heart attack (ironically, while he was in the hospital emergency room awaiting news of JFK's fate), a third probable heart attack at the age of 63, a confirmed massive heart attack at the age of 64, and a fifth and final fatal heart attack on January 22, 1973, at the age of 65. Through it all, he kept on smoking, eating crap food, and not exercising in defiance of medical advice.

Johnson's autopsy results weren't really surprising to anyone who knew him. Two of the president's main coronary arteries were completely blocked, and the third was 80% blocked.

Doctors already knew this, though. In fact, bypass surgery — which is often done to save the life of someone with coronary artery disease — was ruled out in Johnson's case because there was so much scarring on his heart from previous heart attacks that clearing the blocked arteries wouldn't have been enough to save him, as reported by The New York Times.