Dwight Eisenhower's Lack Of Response To Emmett Till's Murder Spoke Volumes

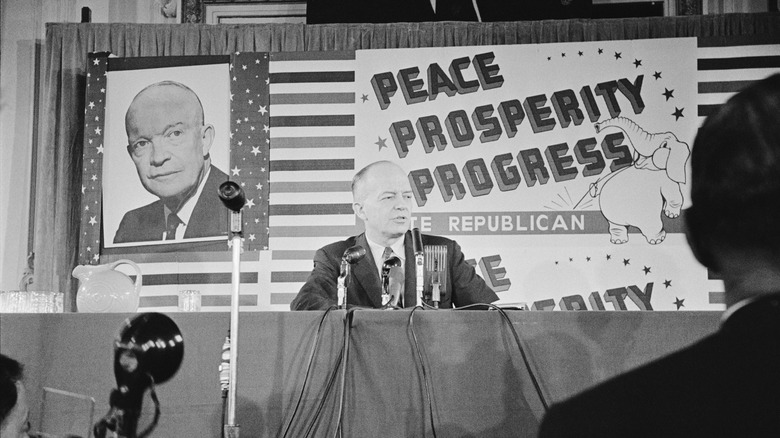

President Dwight Eisenhower was a hugely popular Republican president whose two terms in the White House between 1953 and 1961 saw seismic changes that transformed American society. Eisenhower garnered respect from his fellow Republicans and confidence from American voters because of his long military service. As well as cutting his teeth as a non-combat tank unit commander during World War I and later serving overseas, he served as Supreme Commander of Allied Expeditionary Force in Europe during World War II and became a five-star U.S. Army general. His background and perceived sense of duty towards his country buoyed Eisenhower to a landslide election victory.

Upon taking office, it seemed that the new President of the United States was completely in support of the burgeoning Civil Rights movement, telling the nation in his first State of the Union address: "I propose to use whatever authority exists in the office of the President to end segregation in the District of Columbia, including the Federal Government, and any segregation in the Armed Forces[,]" essentially completing a policy that had first been announced by President Harry Truman back in 1948.

However, though Eisenhower made it seem clear in public that he was in support of equal rights, his reaction to the heinous murder of Black teenager Emmett Till reveals that his views on race in America were not as clear-cut as his administration's steps towards desegregation would have you believe.

Eisenhower and the murder of Emmett Till

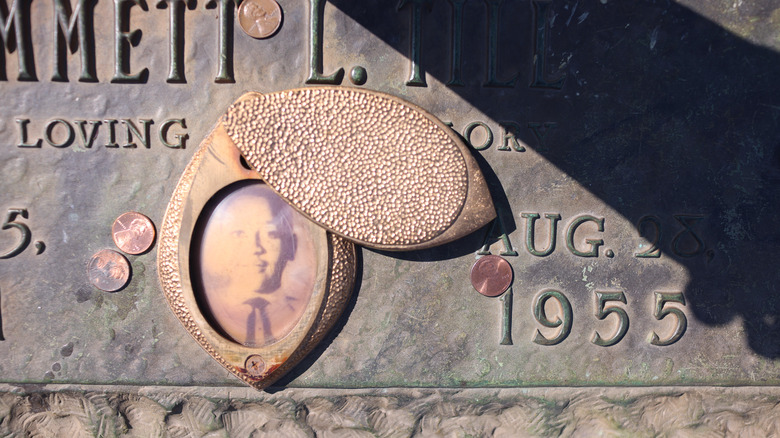

On August 28, 1955, 14-year-old Emmett Till was abducted from the town of Money, Mississippi, where he was visiting family. According to History, Till's abductors were two local white men who accused Till of making comments and advances toward one of their wives, who worked in a local store (years later, the woman would admit that her claims were fabricated, per the same source). Days later, Till's mutilated remains were discovered floating in the nearby Tallahatchie River. He had been beaten, tortured, and shot.

The brutality of the racially-motivated attack shocked Black communities across America, while the subsequent acquittals by an all-white jury of the two white men who had taken his life caused such widespread outrage as to supercharge the Civil Rights movement's push for justice and equality. According to MSNBC, Till's mother, Mamie Bradley, who was instrumental in drawing attention to the case by allowing her son's open casket to be photographed by journalists and the image to be circulated in magazines, telegrammed President Eisenhower days after her son's murder, asking for justice and asking for a "direct reply." None, however, was received.

Eisenhower's deafening silence

It is perhaps so surprising that President Eisenhower never took steps to reply to Mamie Bradley, whose son's horrific killing remains one of the seismic events of the era and which went on to have such an effect on American society, that his lack of response might seem as though it were a mistake or oversight. But in fact, historians have pointed out that Eisenhower's silence on the murder of Emmett Till was in keeping with a privately ambivalent attitude towards the Civil Rights movement's push for racial equality.

Per MSNBC, though President Eisenhower announced his aim to end segregation in the military in 1953, in private, he was far from embracing the prospect of desegregation as a whole, reportedly telling a dining partner that southern white Americans who opposed the end of segregation in schools "are not bad people. All they are concerned about is to see that their sweet little girls are not required to sit in school alongside some big overgrown Negroes."

According to the same source, when the end of school segregation came into effect with the "Brown v. Board of Education" ruling on 1954, Eisenhower was less than empathic, claiming he would simply "obey" the ruling. He was also noticeably hesitant to lend his voice to the cause of Civil Rights when asked by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Though Eisenhower's administration made way for the Civil Rights Act which would become law in 1964 under President Lyndon Johnson, it appears with hindsight that perhaps change was going to happen despite him, rather than through any intervention on his part.