The Messed Up Truth About The 1990s Music Industry

If you were around in the '90s (or, alternatively, if your parents were), then you probably have some warm and fuzzy feelings about the music of that era. (Most of it, anyway — the decade did seem to have a disproportionate number of massively annoying smash hits.) To be sure, lots of great, iconic music came out of the rap, grunge, and EDM genres, and the perpetual mixed bag of pop wasn't really any heavier on the schlock than any other decade.

'90s music, though, suffered from the same major problem as the music of every other era: the actual music industry. Yes, the '90s were a time of great change and upheaval not just for a number of genres, but for the industry itself: CDs quickly became the dominant format only to be promptly challenged by the rise of digital music, and the role of music videos in promotion changed drastically, for example. But the shady business practices and cash-driven approach to decision-making that defined the industry in previous decades remained firmly in place, and in many ways, the '90s were the sketchiest decade to that point to be a professional musician — or a fan. Here are the most messed-up aspects of the '90s music industry.

The biggest concert ticket outlet went to war with the biggest band

Avid concertgoers have found their hobby getting more and more expensive for decades, and the trend toward more pricey concert tickets began in earnest in the early '90s. According to the Los Angeles Times, it was then that the country's biggest ticket seller, Ticketmaster, acquired its biggest competitor, Ticketron, which enabled it to ramp up a practice that music fans already weren't too keen on: Charging hidden "service fees" that, depending on the ticket price set by the venues, could increase the cost of a ticket by 50% or more.

Fortunately for the fans, the Justice Department — concerned about Ticketmaster's all-but-cornering of the market — approached the biggest rock band on the planet at the time, Pearl Jam, about a possible counter-offensive (via Rolling Stone). In 1994, at the DOJ's urging, Pearl Jam cut ties with the ticket giant, filed a formal complaint with the DOJ, and mounted their own darned tour, demanding that venues charge only an $18 flat fee and a reasonable $1.80 service charge. Yay! Ticketmaster backed right down, and — oh no, wait. While the ticket behemoth did trim some of its more exorbitant fees, the antitrust probe against it was thrown out, and Pearl Jam's DIY tour collapsed amid logistical difficulties, as also reported by the Los Angeles Times. Welp, all's well that ends well — except this didn't, and to this day, the practice of tacking hidden fees onto concert tickets continues largely unchecked.

One court ruling changed rap music forever

The controversy around sampling is nearly as old as rap music itself, as that genre was created by wildly inventive inner-city youths with easier access to turntables and records than guitars and drums. Today, the art of constructing compositions out of carefully curated, often heavily processed pieces of other compositions is recognized as just that, an art form — but in the '80s and '90s, many of the sampled artists who unwittingly contributed to rap's growth viewed it as simple theft. Of course, with no legal precedent to refer to, lawsuits over sampling mostly (with some notable exceptions involving out-of-court settlements) went nowhere — until 1991, when that precedent was established by Judge Kevin Duffy, according to NPR.

The issue before Duffy: The late, great Biz Markie's tune "Alone Again," which prominently sampled singer-slash-songwriter Gilbert O'Sullivan's 1972 hit "Alone Again (Naturally)." In this case, there would be no settlement, and the decision handed down by Duffy was as astonishing as it was far-reaching. He ordered Biz to pay a cool quarter-million dollars, barred his label from continuing to sell the album on which the song was featured, and recommended that Biz be tried in criminal court for theft (no, really). That never happened, but as noted by Pitchfork, the decision effectively kneecapped all but those artists who could afford to pay to clear samples with the original artists — a situation which has dictated how rap artists practice their craft for the last three-plus decades.

The consolidation of radio stations killed diversity on the airwaves

If you listened to a lot of radio in the mid-to-late '90s, you may have noticed a slight change to your favorite station's playlists. That is, they began to shrink until they seemed to only play the same 20 or so songs over and over again. You may have also heard said station begin referring to something called "Clear Channel," which was a media conglomerate that once owned a few dozen stations, because that's all it legally could own. But, as noted by LA Times reporter Jeff Leeds (via PBS), that all changed in 1996, when the broadcast lobby successfully implored Congress to help the struggling radio industry by removing that cap. Overnight, instead of a hard limit of 40 stations, a huge company could buy as many stations as it wanted — and, also seemingly overnight, Clear Channel bought up roughly all of them.

With one conglomerate in control of all those playlists, the effect was noticeable and immediate. If you weren't listening to those same 20 songs on a Clear Channel station, you were probably listening to a slightly more diverse "JACK" station owned by Canadian conglomerate SparkNet Communications (via Radio Today), and neither were exactly kind to smaller artists or subgenres. Perhaps ironically, the advent of streaming in recent years has put Clear Channel (rebranded as the slightly friendlier-sounding iHeart Radio) on the financial ropes, according to Texas Monthly — but you still can't find much diversity on the radio to this day, and that one act of Congress in 1996 is why.

MTV went from playing everything to playing nothing

It's impossible to describe the impact MTV had from the day it showed up on your local cable carrier — on music, on television, on the radio, and on pretty much everything else. The channel launched on August 1, 1981, and while it took a bit for it to spread to all of the major markets, its power to break artists nobody had ever heard of — artists like Wall of Voodoo, The Tubes, and Culture Club — and turn them into overnight sensations soon became undeniable. Later in the decade, MTV helped facilitate the advent of rap, and in the early '90s, it did the same for grunge ... but around that same time, a noticeable shift started to happen.

Beginning with the reality series "The Real World" (the first non-scripted reality show ever, according to CNET), MTV began to focus more on increasingly weird reality offerings, and much less on music, which was, you know, the "M" part of its name. By the end of the '90s, reality-slash-competition shows like "Lip Service" and "Road Rules," along with straight-up reality series like "True Life" and "FANatic," had muscled their way into more and more of the network's programming, and by the middle of the next decade, music had all but disappeared from the rotation. Speaking with CNET in 2011, former VJ Adam Curry explained the reason for the change, which should surprise no one: "It was the best business decision they ever made." At that time, according to Curry, MTV was raking in $4 billion per year — great for MTV, not so great for musicians and their fans.

The '80s obsession with music censorship continued to affect the industry

It might sound odd if you weren't around, but there was a time in the mid-'80s when the government decided to go to war with music — specifically, with lyrics that were deemed by a bunch of senators' wives to be inappropriate. Their organization, the "Parents' Music Resource Center" or PMRC, is the one responsible for those "Parental Advisory — Explicit Lyrics" stickers that are probably featured on all of your old CDs, and the damage it did to freedom of expression continued to have a dramatic effect in the '90s.

For one thing, censorship likely played a role in MTV's transformation. According to the National Coalition Against Censorship, between 1984 and 1994, the number of videos the network was forced to edit due to content rose from one in 10 to one in three, which really sounds like a hassle for everyone involved. For another thing, that Parental Advisory sticker had an immense chilling effect. As outlined in a scholarly paper by Shoshana Samole for the University of Miami (we're all scholars here), Wal-Mart — the nation's largest retailer — refused to carry any release carrying it, a practice that continues to this day. On the bright side, all the hostility toward anything remotely badass forced '90s artists and their mix engineers to master the "clean version" — alternate versions of songs featuring scrubbed-clean lyrics (via NPR) — and who doesn't love those? (Hint: Nobody. Nobody loves those.)

The biggest music festival of the decade was an utter disaster

The '90s were generally a pretty sweet decade for music festivals; it's the decade in which Lollapalooza and Vans Warped Tour were born, and in '94, one of the biggest festivals in history — Woodstock, which took place in 1969 — got a pretty successful reboot. To close out the decade and the millennium, a group of intrepid organizers including veteran promoter John Scher (via the Washington Post) decided to once more capitalize on a name synonymous with peace, love, and all that mushy stuff to stage what was then one of the biggest festivals in history: Woodstock '99. It did not go well.

A combination of poor planning, virtually non-existent crowd control, blazing hundred-degree heat, and a lack of water and shelter combined to turn the event into a powder keg packed with over 200,000 extremely annoyed people. According to SFGate, some of the artists themselves assisted in driving the event toward complete chaos: Those lovable rascals Insane Clown Posse tossed hundred dollar bills into the crowd to predictable effect, that wily scamp Kid Rock demanded that festivalgoers pelt the stage with overpriced water bottles, and that jolly idiot Fred Durst of Limp Bizkit all but openly encouraged a stampede. When it was all over, the festival made headlines for all the wrong reasons ... namely arson, looting, vandalism, and dozens of hospitalized fans. Said Scher in the aftermath, "I'm bummed big time." Eloquent in its brevity.

Rap went from counterculture to mainstream

The period from 1986 to 1993, give or take a year or so on either side, is often referred to as the "Golden Age of Rap." During this time, the genre went from a borderline-novelty regional thing to a worldwide phenomenon exploding with innovation and creativity, a status it has retained to this day. Psych! Unfortunately, beginning in the mid-'90s, rap inexplicably went from lyrical and political to simplistic and gangster-y (some outliers, like Eminem and OutKast, notwithstanding), and today, it can seem like an impossible task to cut through the mumbly, clunky clutter to find what good stuff remains. The reason for the change? Well, it probably has to do with money, as the genre is more popular than ever — and if one legendary essay published online in 2012 is to be believed, it's even more nefarious than that (via Business Insider).

In it, an anonymous "decision maker" within the music industry describes a secret meeting of bigwigs he attended in the mid-'90s, where representatives of the private prison industry were in attendance. Their job, they said, was to keep those prisons filled — and those in the rap biz were being enlisted to help, by way of pushing violent, druggy content in lyrics. Our anonymous hero was horrified, shortly thereafter leaving the industry and watching in dismay as the plan came to fruition. Now, this probably isn't exactly true — but the fact that it's even remotely plausible speaks volumes about rap's astonishing metamorphosis, and the bizarre quickness with which it happened.

Many of the decade's top-selling artists went broke

It's no secret that the music business isn't exactly the least shady of industries, and there have always been managers, promoters, and executives more than willing to take advantage of hot artists to their own ends. But some of the more ultra-shady practices, as outlined by legendary producer Steve Albini in his essay "The Problem With Music," really came into vogue in the '80s and '90s — notably, the practice of throwing absurd amounts of money at new signees, only to forcibly recoup all those Benjamins for stuff like studio time and promotional expenses. This resulted in '90s icons like Toni Braxton (via BBC) and Hole front woman Courtney Love (via The Fix) going broke, sometimes filing multiple bankruptcies — and perhaps nobody got shafted harder than TLC.

Despite selling more records than any girl group in history other than the Supremes, TLC endured financial hardships even at the height of their fame as a result of poor management and wack contracts. As reported by Beat, all three members filed for bankruptcy on July 3, 1995 — at the exact moment their hit single "Waterfalls" was screaming toward the top of the Billboard chart. A decade and a half later, in 2011, that same publication was reporting that lead singer Tionne "T-Boz" Watkins was filing for bankruptcy again — for the second time that year. Unfortunately, the practice of artist-shafting has only gotten worse with the advent of streaming, as — according to Digital Music News — today's hot artists typically earn jaw-droppingly little for racking up millions of streams.

The exploitation of young stars was horrifying

It's pretty common knowledge that many of the Disney Channel's stars of the early '90s became the massive pop stars of the late '90s — think Justin Timberlake, Britney Spears, and Christina Aguilera. Of course, some of these — like Spears, for instance — became the cautionary tales of the '00s, unprepared as they were for the ridiculous level of fame they were thrust into. As pointed out by Complex, for every former child star of the '90s who successfully made the transition to adult stardom, there seems to be a dozen (Lindsay Lohan, Amanda Bynes, Demi Lovato, Justin Bieber, and on and on) who struggled mightily.

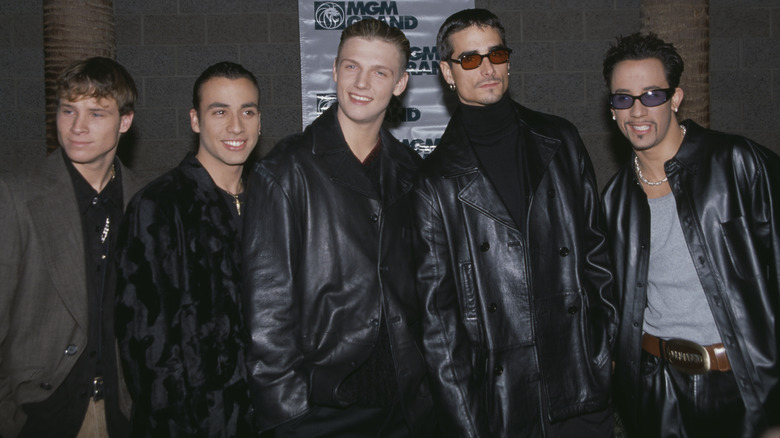

If there's one individual who exemplified the decade's seeming ultra-willingness to chew up and spit out young stars, it would be Lou Pearlman, the infamous former manager for the Backstreet Boys and *NSYNC, among others. As outlined by In Touch Weekly, Pearlman's abuses were myriad, from the financial (he pocketed the vast majority of the Backstreet Boys' earnings during the height of their fame, to name one example) to the allegedly sexual. Said former LFO singer Rich Cronin, one of Pearlman's young charges, "Honestly, I don't think Lou ever thought we would become stars ... I just think he wanted cute guys around him; this was all an excuse. And then lightning crazily struck and an empire was created. It was all dumb luck." Perhaps, but the $300 million Ponzi scheme Pearlman was running during his rise certainly wasn't (via Washington Post); he was charged with financial crimes and sentenced to prison in 2008, where he died eight years later (via ABC News).

A few Swedish songwriters and producers rose to dominate pop

Sweden has a long tradition of involvement on the global pop scene; just look at ABBA, Ace of Base, and The Hives, who all rose to international prominence in their respective eras. Here's something you may not know, however: The way that pop music has been composed, mixed, and recorded since the mid-to-late '90s has been the result of the influence of a handful of Swedish dudes, and one Swedish dude in particular. His name is Karl Martin Sandberg, but if you know him at all, you know him as Max Martin (via New Yorker).

Martin made his bones in the early '90s in his home country, working under legendary producer Dag Krister Bolle, aka Denniz PoP. In 1995, he hooked up with Lou Pearlman and the Backstreet Boys, and he ended up writing and producing the bulk of their 1997 debut album, including "Everybody (Backstreet's Back)," which is now stuck in your head for the rest of the day (via "The Song Machine"). Over the next two decades-plus, Martin and his proteges would virtually define the sound of pop radio, working with the likes of Kelly Clarkson, Britney Spears, Pink, Usher, Avril Lavigne, Katy Perry, Taylor Swift — the list could go on, but you'd literally be here naming legendary pop artists all day. The Swedish juggernaut and his acolytes made it tough to get your foot in the door as a budding composer or producer and contributed mightily to the homogenezation of the pop sound over the last 25 years — but consumers don't seem to care, as Martin (via HuffPost) has notched more top 10 hits than the Beatles ... a lot more.

The seeds of the Loudness War were sown

When it comes to the way music is actually recorded — and, therefore, the way the final product sounds — few periods were more significant than the '90s, and not in a fantastic way. The rise of digital audio workstations like Pro Tools removed a lot of warmth from recordings (via Reverb), to the extent that many engineers would simply dub digital tracks back onto tape to add it back in. Part of the issue, though, was the new dominant medium — CDs, which removed a limitation of vinyl that actually ended up making many recordings sound much, much worse.

See, if a mix engineer pushed the limits of loudness prior to CDs, it wouldn't work — played back on a vinyl record, the earth-shaking volume would force the needle right out of the groove. Digital recording enabled engineers to go buckwild with pushing the volume shelf, to the detriment of the finished product (via NPR). While this trend was born in the '90s, it arguably reached its nadir with Metallica's 2008 album "Death Magnetic," which famously sounds like it's being played on a single loudspeaker which has been gently placed inside a filthy dumpster. This trend likely played a part in vinyl's unlikely resurgence within the last decade or so (via New York Times) — because it turns out that when it comes to recorded music, even if your band plays music designed to wake the dead, sheer volume isn't everything.

One song changed the way pop vocals are recorded to this day

The '90s were a decade in which terrible trends tended to snowball out of control pretty quickly. The most terrible of them all took a while to gain traction, but once it did, it posted up on the pop scene like a crappy, freeloading roommate who doesn't pay rent and refuses to leave. It started, though, with literal genius: In 1997, brilliant research engineer Andy Hildebrand used his enormous brain to invent an audio plug-in that could correct the pitch of an incoming signal, allowing even the pitchiest singers to sing in tune (via Priceonomics). He named his invention "Auto-Tune," and it would take all of one year before someone used the innovation in flagrant violation of its intended purpose.

You see, Auto-Tune, used properly, sounds subtle and completely natural — but in 1998, producers Mark Taylor and Brian Rawling discovered that if you dialed each setting down to zero, the result was the complete opposite of that (via Musician Wave). Sure, it would force a vocal right on pitch, and it also made the vocalist sound like a soulless android. Elated, Taylor and Rawling applied the technique to the lead vocal on Cher's hit single "Believe" — and that was it, folks, game over. The aggressively wrong use of Auto-Tune swiftly became a mainstay in popular music, and as noted by NPR, it has remained so ever since.