The Untold Truth Of Ben-Hur

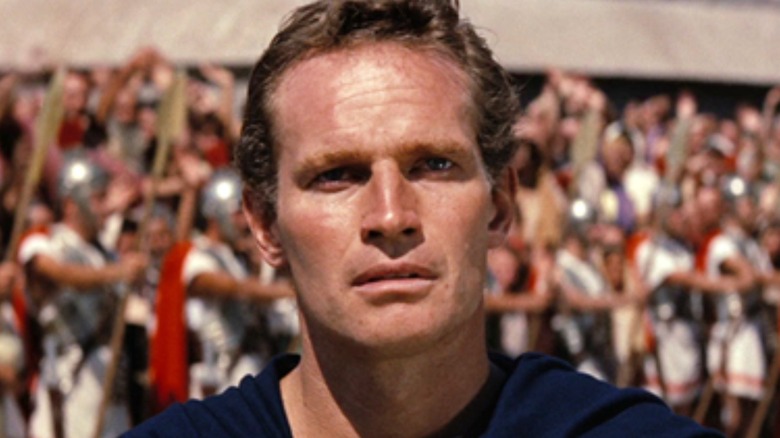

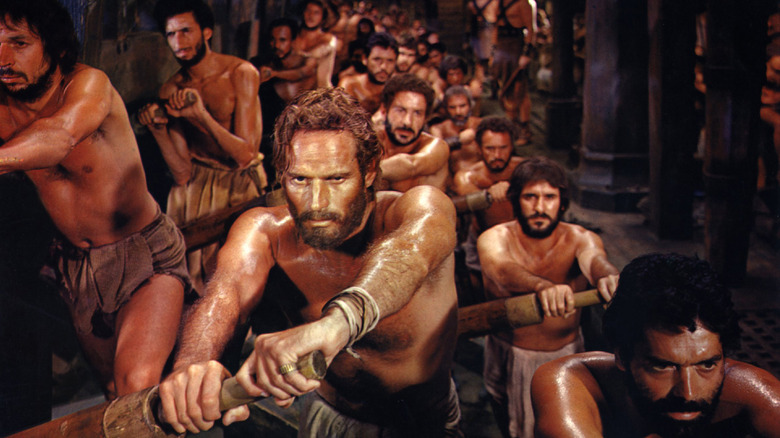

"Ben-Hur," one of the greatest Biblical epics of all time, has remained one of the most popular films since its release at the apex of Hollywood's Biblical film era in 1959. At a time when historical epics employing thousands of extras were being churned out regularly, "Ben-Hur" still stands with 1956's "The Ten Commandments" -– another film with Charlton Heston in the main role — as one of the most beloved and enduring of them all.

The novel "Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ," written by General Lewis Wallace and published in 1880, had been staged many times over by the time it was first filmed in 1907, The Guardian notes. The well-known 1959 rendition was actually the third film remake of "Ben-Hur;" the stunning silent epic of 1925, containing what some still believe to be the best chariot race footage, was the second. However, the classic "Ben-Hur" of 1959 brought the engaging story to a new generation, filmed in Panavision in ultra-wide format, as noted by American Cinematographer, with a stirring score and huge stars like Heston and director William Wyler winning Academy Awards for their work.

Here's the untold truth about this epic film.

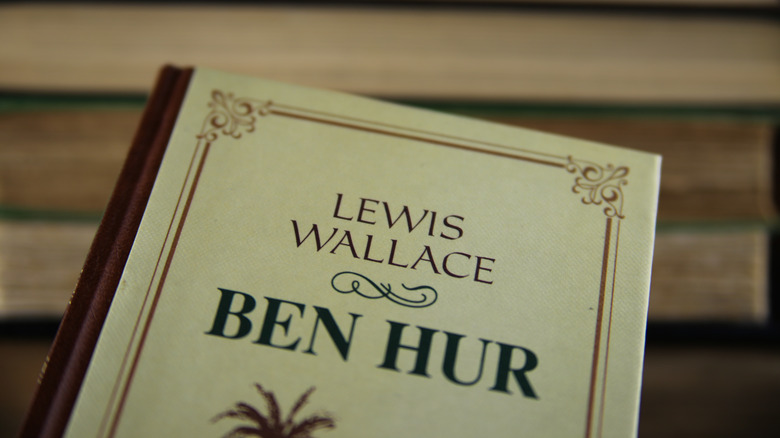

The Ben-Hur films are based on a book of historical fiction and the Bible

"Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ" has never been out of print since it was first published. The book, written by a Civil War veteran who had a religious conversion in his later years, was enormously popular, as the National Endowment for the Humanities states — so much so that only "Gone With the Wind," published in 1936, eventually overtook it on the bestseller list.

Lewis Wallace's book and the subsequent films made from it all explore not only the themes of man's inhumanity to man and the desire to seek vengeance but the power of kindness and forgiveness as well, which wins out in the end. Although the main character, the Jewish prince Judah Ben-Hur, is fictional, the film is true to the Bible in other areas, especially its theme of redemption that characterizes the message of Christianity.

Although meme-worthy lines such as "Hate keeps a man alive" and "We keep you alive to serve this ship" perfectly portray Judah Ben-Hur's burning desire for vengeance, they were actually written by the 1959 film's writers, including Gore Vidal, Karl Tunberg, and Christopher Fry, as the NEH states. But many lines in the book echo the Bible, as noted by Godtube, including those uttered by Esther, imploring Ben-Hur to forgive his enemy, Messala: "I've seen too much what hate can do. ... But I've heard of a young rabbi who says that forgiveness is greater and love more powerful than hatred."

Director William Wyler had withering criticism for star Charlton Heston

Incredibly, despite universal acclaim for Charlton Heston's portrayal of the titular Ben-Hur — who survived unimaginable trials, including being sentenced to a Roman slave galley –- director William Wyler took Heston aside for some criticism midway through filming. According to an interview Heston's son Fraser gave to Jesus Freak Hideout, Wyler told the star bluntly, "Chuck, you need to be better in this part. I don't know how to tell you to do that, but you need to dig down deep and find that character within you and bring that out."

Heston recalled that meeting in his commentary on 2003's DVD of the film, seemingly still amazed at the criticism, especially as he had already starred in many films, including "The Biggest Show on Earth" in 1952, "The Naked Jungle" in 1954, and the groundbreaking Biblical epic "The Ten Commandments" just the year prior, per Britannica.

True to his reputation for humility, however, Heston took the criticism on board; his son told Jesus Freak Hideout that "it was the right thing to say to him at that time. ... he did dig down deep, and of course, both he and Wyler won an Academy Award." As the Hollywood Reporter wrote in its 1959 review of "Ben-Hur," "Charlton Heston completely identifies himself with the inspirational role of Judah Ben-Hur, his dramatic struggle against the tyrannical subjugation of the Jews, and his triumph in finding a meaning of life."

Ben-Hur's crucifixion scene reduced Charlton Heston to tears

Although it wasn't known publicly at the time, and most of Heston's roles up until then had featured him portraying strong, silent types, he broke down while filming the crucifixion scene near the end of "Ben-Hur." As son Fraser Heston relates in an interview with Jesus Freak Hideout, "The crucifixion of Jesus was the last scene in the film and Dad basically lost it ... he's not supposed to be in tears, but [he] practically was and you can see it in his face, just looking up at this very realistic recreation of Golgotha."

His portrayal of anguish is also magnificent in other scenes, in which he realizes he cannot kill Messala despite the terrible wrongs he has done to his family. Their final scene together, as related in "A Wonderful Heart: The Films of William Wyler" by Neil Sinyard, was "a scene which is an angry and agonized inversion of their initial joyous reunion. Ben-Hur's cry of anguish ... exactly echoes the tortured cry he made all those years ago when he could have killed Messala but did not."

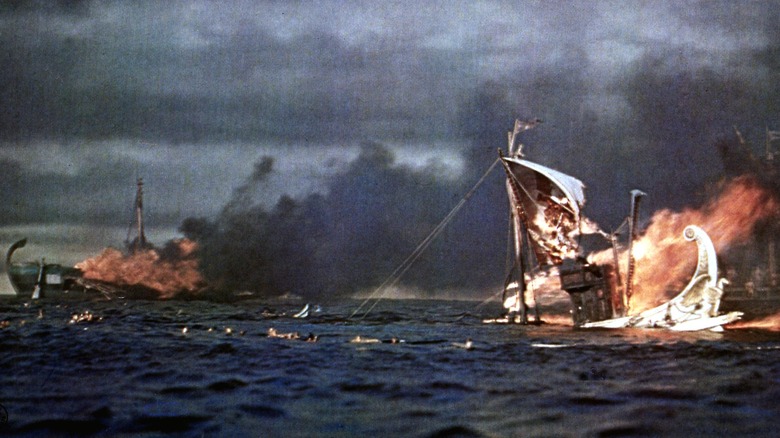

The sea battle was filmed in tanks in California

The epic sea battle which ended up reversing the character Ben-Hur's fortunes wasn't filmed on the Mediterranean: As related in the book "The Wizard of MGM" by Metro Goldwyn Mayer's art director A. Arnold Gillespie, unlike the great verisimilitude characteristic of many other scenes, water tanks on the MGM lot in California were the backdrop of this epic clash between Roman and Macedonian galleys, while the inside and deck shots of the galleys, as well as final editing and finishing, were completed at Rome's Cinecitta, notes America Cinematographer.

With gigantic tanks and miniature ships, there were different background murals painted for every scene. Gillespie was tasked with recreating the scenes using radio-controlled wooden ship models, catapults, oars, and even tiny rubber models of sailors, all of which moved under his direction. Roman admiral Quintus Arrius' magnificently-detailed trireme measured only 20 feet, 6 inches long by 4 feet wide, and stands 10 feet, 10 inches from its keel to the top of its masts, Gillespie's memoir records.

The actor portraying Jesus Christ in Ben-Hur never showed his face

"Ben-Hur" employed a unique film technique in that the actor portraying Christ never showed his face, despite several scenes in which he interacted with Ben-Hur, including when he gave water to him after he had cried out to God for help, and when Ben-Hur likewise came to Jesus' aid when He needed water as He carried his cross. This technique, noted in the LA Times, subtly placed Jesus in the heart of the story. The technique evoked an aura of majesty that surrounds Christ every time he appears, as Gabriel Miller notes in his essay on "Ben-Hur."

Perhaps the most memorable moment in the entire film is when the Roman decurion, or cavalry officer — who had just denied Ben-Hur water — looks into Jesus' face. As the Hollywood Reporter notes, again, Christ's face is invisible. The audience only sees the face of the Roman melting as he realizes the sanctity of Jesus; the officer turns away, mute.

The American operatic tenor Claude Heater (pictured with Charlton Heston in 2003), whom Director William Wyler had discovered at a concert in Rome, portrayed Christ. Although he wasn't even credited in the movie, this actor's portrayal of the man from Nazareth is still memorable today. Heater later stated, per Hollywood Reporter, "There were people on the set who would see me, drop to one knee and make the sign of Christ."

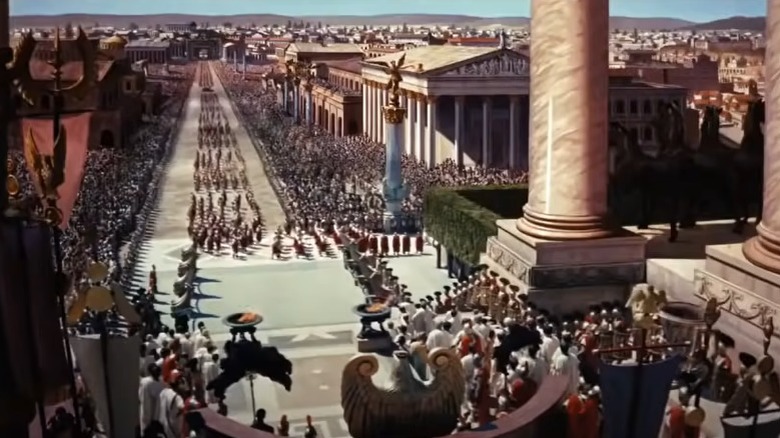

Some scenes had up to 15,000 extras

The Sermon on the Mount, the trial and crucifixion of Jesus, the chariot race, and the triumphal parade in front of the Emperor in Rome were some of the historic scenes requiring thousands of extras to recreate for "Ben-Hur." The riotous chariot race alone may have featured as many as 15,000 cheering and jeering fans in the 18-acre arena complex built at Cinecitta to resemble the actual Circus Maximus at Antioch, according to The Irish Independent.

There were thousands of extras used at Cinecitta, and the jobs were desperately needed in postwar Italy. On June 6, 1958, a riot broke out when only 1,500 were needed for filming after 6,000 had been hired to cheer in the stadium the day prior; 40 policemen were on hand to quell the disturbance, Variety notes. The unprecedented number of horses used in the film, numbering 2,500 in all, were flown in from abroad, including Lippizaner stallions, who gave their all in recreating the chariot race. The Cinecitta arena set, with a base of tons of sand flown in from Mexico to provide the best footing for the horses, was the largest ever created for a film up to that time, Polo Online states. It could seat fully 10,000 spectators, according to TIME.

1959's Ben-Hur featured the first Israeli actress in a major Hollywood role

Haya Harareet, born in Haifa, Israel, to Polish immigrant parents, glowingly portrayed Esther, the slave girl owned by the Ben-Hur family who became the love interest of Judah. Harareet was the first Israeli actress to be signed to a 4-year movie deal in Hollywood, Haaretz reports, paving the way for non-European actresses in major Tinseltown roles. She owed her Hollywood opportunity to William Wyler, who had met her at the Cannes Film Festival in 1955, on whose insistence MGM located her and gave her a screen test.

The Hollywood Reporter's review of the film on its release in 1959 gushed, "Haya Harareet as Esther gives a striking, seemingly guileless performance as Ben-Hur's former slave and love interest." Variety reported at the time that Harareet "represents a welcome departure from the standard Hollywood ingenue."

Although, as reported by The Jewish Post, she immediately catapulted to stardom as a result of her portrayal as the steadfast Esther, Harareet never returned to that kind of fame again in her career. Nevertheless, she opened the door for later Israeli actresses in Hollywood, including Natalie Portman — not to mention Gal Gadot, who was for a time in talks to reprise Harareet's role in the 2016 version of "Ben-Hur," per The Hollywood Reporter – and Ayelet Zurer, who played Judah Ben-Hur's mother in the 2016 movie.

The 1959 Ben-Hur had the largest budget and set ever seen

With a budget of $15.175 million, the Biblical epic had its work cut out to make money for MGM, but it immediately became a worldwide smash hit, garnering $73 million in domestic proceeds alone after its release, Nash Information Services notes. Constructing the arena for the chariot race at Italy's iconic Cinecitta Studios outside Rome over an incredible 18 acres of land, plus the shoot for the race itself, cost an astounding $1 million. That footage represented the single greatest expenditure on any movie up until that time, according to Variety, which upon the movie's release described the sets as "absolutely beyond belief — and description. Both interiors and exteriors are so magnificent they should be preserved along with the Rome of the past."

But the incredible expense and painstaking work were all well worth it: "Ben-Hur" was the highest-grossing film of 1959, representing the second-highest movie earnings ever at that time after only "Gone with the Wind," the Center for Israel Education notes. Rotten Tomatoes lists the 1959 version of "Ben-Hur" in a solid second place for the most memorable of all Biblical epics, noting that its powerful storyline and evocative Biblical images created a "potent mix that crushed all box office competitors during 1959."

The thrilling chariot race even outpaces the 1925 film rendition

The famed Hollywood stuntman Yakima Canutt and Andrew Marton, who respectively staged and directed the epic scene, expertly captured the thrilling chariot race in 1959's "Ben-Hur," which took a mind-boggling five months to shoot, per American Cinematographer. A total of 18 chariots were constructed for the scene. Incredibly, Canutt taught both Charlton Heston and Stephen Boyd, who played Heston's nemesis Messala, how to drive the chariots just before shooting the film; they did all the driving in the film themselves, except for the two most dangerous maneuvers, American Cinematographer notes. As Marton says in American Cinematographer, producer Sam Zimbalist — who, as Variety relates, later died of a heart attack on set, just before filming concluded — gave him "one warning — if anything happened to Heston or Boyd, there would be no picture."

Canutt and Marton created one of the most thrilling scenes in movie history with their brilliant staging and direction, as noted in "A Talent for Trouble: The Life of Hollywood's Most Acclaimed Director, William Wyler." Canutt's son Joe, working as the stuntman for Heston, flew over the rails in an unforgettable –- and completely unscripted -– moment in the race. According to onlookers, Yakima Canutt's face went white as he watched his son fly through the air, only to somehow climb back into the chariot, suffering only a scraped chin for his pains, as Charlton Heston himself recalled in his autobiography, "In The Arena."

There are many urban legends surrounding Ben-Hur

Many urban legends sprang up regarding the chariot race, battle scenes, and other epic moments in the 1959 version of "Ben-Hur," among them that horses died during the race, Charlton Heston wore a wristwatch in one scene, a red Ferarri somehow made its way into the movie, and that one stuntman died. None of these allegations are true, although producer Sam Zimbalist died on the Rome set after suffering a heart attack, as noted by Mental Floss.

As Charlton Heston reported in his book "In the Arena," not one horse was killed in the filming of the movie, in contrast to the tragedy in the 1925 version, when as many as 150 horses were rumored to have been injured and/or killed, according to the magazine True West. Heston also did not wear a wristwatch in any scene of "Ben-Hur," nor was any stuntman killed, according to the feature commentary he provided for MGM's DVD release of the film in 2003, as noted by Jon Solomon in "Ben-Hur: The Original Blockbuster."

Ben-Hur won a record 11 Academy Awards

Although the film was a tour-de-force for Charlton Heston, whose portrayal of the titular wronged man who finally found redemption and forgiveness was unforgettable, "Ben-Hur" also snagged Oscars for its director, William Wyler, cinematographer Robert L. Surtees, and music composer Miklos Rozsa, whose score, including a moving overture and entr'acte, was the longest thus far in movie history. Per the Oscars, Hugh Griffith, who played the charming Sheikh Ilderim backing Ben-Hur in the epic chariot race with Messala, also won for Best Supporting Actor. The movie also won in the categories of Color Art Direction, Set Decoration, Cinematography, Costume Design, Sound (won by the Metro-Goldwyn Mayer Studio Sound Department), and Special Effects.

Setting a record that was not broken until "Titanic" in 1997, with "The Lord of the Rings" tying it in 2002, per Variety, "Ben-Hur" took home an astonishing 11 Academy Awards out of the 12 for which it was nominated. Incredibly, it was the only Academy Award nomination for Heston aside from a special Oscar at the end of his career.

Ben-Hur is included in the Library of Congress' National Film Registry

In 2004, "Ben-Hur" was chosen for inclusion in the United States National Film Registry of the Library of Congress due to its status as a "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" achievement. Chosen from a list of almost 1,000 films that year, it was among those nominated by the public, Library staff, and film experts, the Library of Congress announced. The Registry was created out of the National Film Preservation Act of 1988.

"Ben-Hur" stands with other films such as "Judgment at Nuremberg," "Spartacus" and "Saving Private Ryan," among others, as one of the most emblematic films of our time, many of which portrayed seminal moments in world history. As the newspaper the Forward notes, that only stands to reason, since the book on which it was based was even more popular in its day than the groundbreaking antislavery novel "Uncle Tom's Cabin." In its time, the Forward states, "the novel had already become a cultural force that, in modern terms, can only be compared to 'Star Wars.'"

1959 Ben-Hur film used more than one million props

Because of MGM's desire for complete historical accuracy, more than 1 million props were purchased or created for the filming of "Ben-Hur," including enormous sculptures, working four-horse chariots, and miniature warships with moving parts and figures aboard them. A total of 300 sets were built, and 100,000 costumes were sewn, TIME reports, requiring years of painstaking historical research; 200 craftsmen and artists labored in the effort, The Irish Independent notes, using 1 million pounds of plaster to create friezes and sculptures.

Two four-story high colossal sculptures in the middle of the five-story high chariot racing arena were painted in gold, rivaling the spectacles of ancient times, according to Variety, whose correspondent gushed over the creations by Edward Carfagno of MGM's props department. The Spina, the central structure around which the horses raced, measured a historically-correct 1,000 feet long, notes Western Horseman. The sweeping cityscape of Rome painted on a giant canvas that served as a backdrop for several scenes, created by George Gibson, a legendary backdrop creator at MGM, is preserved today by the firm J.C. Backings as the treasure that it is in itself, The Hollywood Reporter relates.