The Tragic History Of Anti-Mormonism

To the minds of many non-Mormon "Gentiles," the Mormons who came to public attention in the 1830s were a serious problem. For one, they represented a threat to their deeply-held religious beliefs. Joseph Smith, the progenitor and prophet of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the official name for the Mormon church), made bold claims that he had interacted directly with God and Jesus Christ. Then, there were rumors of what else might be going on in the sect, such as the shocking practice of polygamy (which the church only publicly admitted in 1852).

Aside from challenging the religious hegemony of the time, Mormons also represented more worldly threats. As PBS notes, they tended to move into cities and towns en masse, creating sometimes powerful voting blocs. At any rate, non-Mormons certainly worried that such a situation could happen and they would then be living under another religious group's rules. Whispers of polygamy and "white slavery" practiced by this religious group certainly didn't help things, either. In addition to dominating local politics, Mormons could also present serious competition for business and land, giving Gentiles all the more reason to greet them with hostility. But it didn't stop with the 19th century. Here's the full, tragic history of anti-Mormonism.

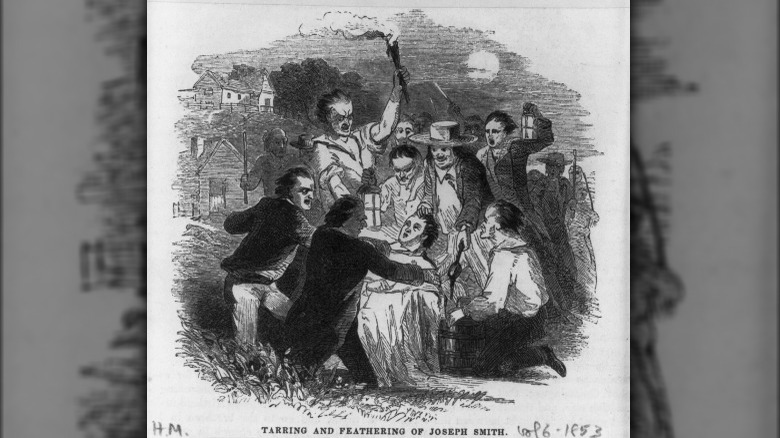

The first serious trouble happened in Ohio

According to PBS, opposition to the Mormons began almost immediately, when Joseph Smith earned the charge of being a "disorderly person" for his boundary-pushing preaching. By 1831, he had claimed to receive divine instructions to move the growing group of Mormons from Western New York to Ohio. That's where the real trouble began. In 1832, agitated by the increasing number of Mormons moving in, the people around Kirtland, Ohio pulled Smith from his home and covered him in tar and feathers.

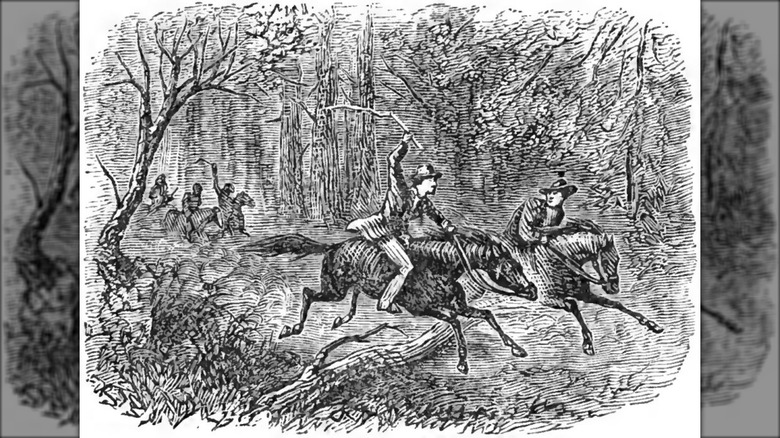

Despite the violence, Smith stayed in Kirtland for years after this incident and even built a Mormon temple in the town, only to leave in a hurry in 1838 (via PBS). The final straw was actually a series of economic misadventures that seriously damaged the Mormons' reputation in Ohio and beyond. Namely, Smith and his associates formed the Kirtland Safety Society Bank, which was shortly hit by not only Gentile suspicion and accusations of financial wrongdoing, but also the economic panic of 1837.

Members of the LDS church began to experience more and more pressure through scattered attacks and increasingly fraught rhetoric that framed them as dangerous, deviant outsiders who didn't belong. As for Smith, a number of civil suits and accusations of bank fraud were so damaging that he fled Ohio for Missouri in 1838 (via Smithsonian Magazine).

The first Mormon War was in 1838

While Joseph Smith and associates were dealing with trouble in Ohio, Missouri Mormons were faced with more serious threats. According to the Missouri State Archives, Smith had first sent missionaries there to convert local Native American tribal members. He then began to proclaim that the state would contain "Zion," the place where the faithful would gather to await Christ's second coming. Gentiles greeted the steady influx of Mormon settlers with dismay, believing that the insular group would establish a stranglehold on local politics. For their part, the Mormons believed that they were only acting both as Americans with the right to practice their religion and as faithful followers of God.

Half-measures, like an 1836 attempt to establish a "separate but equal" county for Mormons, failed. Too many members of the church were emigrating to the area to be contained within the county borders. Relations grew even more tense with an election riot in 1838.

Mormons first responded to the growing hostility with pacifism, but as time went on and tensions increased, their rhetoric became combative. On July 4, 1838, church leader Sidney Rigdon said that Mormons would not make the first move, but if anyone outside the group acted against them, "it shall be between us and them a war of extermination" (via The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints). The formation of a Mormon vigilante group known as the Danites further alarmed many, who saw this as a prelude to real violence.

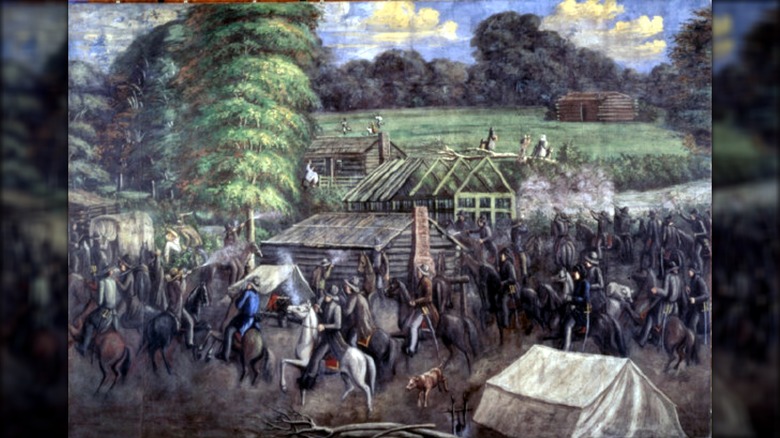

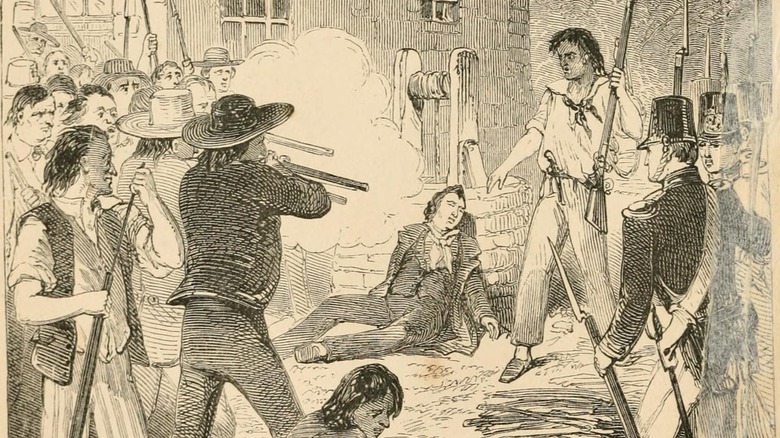

Hawn's Mill slaughter

The tensions in 1830s Missouri grew even more fraught when the governor got involved. In 1838, Governor Lilburn Boggs issued an order that all Mormons were to leave his state or face serious consequences. As he declared in an October 27, 1838 executive order, "Mormons must be treated as enemies, and must be exterminated or driven from the state if necessary for the public peace — their outrages are beyond all description."

According to the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, that order was shortly followed by a vigilante attack against Mormon settlers living at Hawn's Mill (sometimes also referred to as Haun's Mill) on October 30. This had followed a series of increasingly aggressive actions from Mormons themselves in Daviess County, as well as a warning from Joseph Smith himself to leave the area as soon as possible.

Despite the urging to flee that came from the prophet himself, some settlers, perhaps already used to anti-Mormon violence or unable to pick up and move on such short notice, remained at Hawn's Mill. They surely came to regret it. On October 30, 1838, armed men descended upon the settlement, causing many to scatter in search of hiding places. The group killed 17 men and boys, including some who were pulled out of hiding and then shot. Though the vigilantes may not have known about Boggs' order, the governor's rhetoric of extermination and the subsequent slaughter at Hawn's Mill have become inextricably linked.

Joseph Smith was killed in 1844

For many Mormons both then and now, one of the most traumatic results of anti-Mormonism came in the mid-19th century, when the mobs finally cornered the prophet Joseph Smith. Per PBS, he and many other Mormons had fled Ohio and Missouri for Nauvoo, Illinois, attempting to form the next Mormon stronghold there. Yet, aggressive tactics dogged them. According to Encyclopedia.com, tensions were further inflamed when the Mormons' neighbors grew wary of their increasing power and jealous of their economic successes. It got to such a point that yet another governor had decided he'd had enough with this new and alarmingly growing religious group.

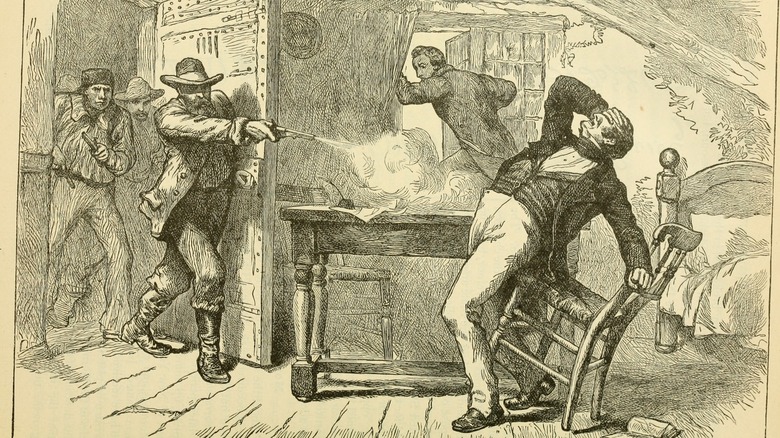

This time, it was Illinois Governor Tom Ford who ordered Smith to turn himself in to the jail in Carthage, Illinois under charges of treason. Smith did so in June 1844. According to PBS, the men tasked with guarding him were openly aggressive, with one jailer even ominously telling someone on June 27, "unless you want to die with him, you had better leave before sundown."

Indeed, a mob stormed the Carthage Jail that day, bursting into the room where Smith and a few other Mormon leaders were held. Joseph, who reportedly fired into the crowd, was shot as he was attempting to escape through a window. He fell to the ground and, within a few short minutes, was dead.

The Illinois Mormon War saw even more violence after Smith's assassination

As one might guess, the assassination of a prophet didn't do much to douse the steadily growing tensions between Mormons and Gentiles. Even before Joseph Smith was killed in the Carthage Jail, Mormons in Illinois had been forming militias, according to Encyclopedia.com.

By this time, however, anti-Mormon sentiment was growing even stronger. Anti-Mormon newspapers could be found throughout Illinois, whipping Gentiles into a suspicious frenzy. By the fall of 1844, Gentile militias were formed to go on a euphemistically named "wolf hunt," as per "A History of Illinois." There were no actual wolves in anyone's sights, however, as it was generally understood that militias were really on the hunt for Mormons. It was soon clear that Mormons could not stay in Illinois without expecting further bloodshed. An exodus was in order.

By 1846, the once bustling city of Nauvoo was practically a ghost town (via Brigham Young University). Many Mormons had left to follow Brigham Young, Smith's successor, to Utah in search of a new stronghold. In September, a mob of about 1,000 descended upon the poorly-defended town. An estimated 150 Mormons held them off for a week, with three losing their lives in the process. Ultimately, the Mormons admitted defeat and drew up a treaty that demanded all LDS church members leave town as soon as possible.

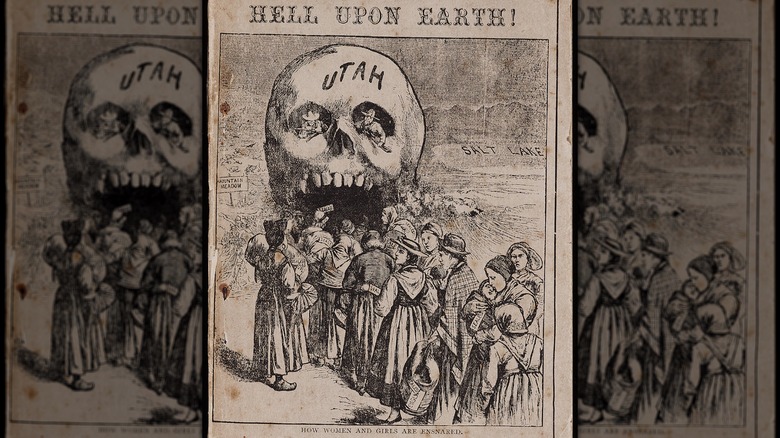

Polygamy came under fire

By the 1850s, it was clear to many Mormons that they would have to find their promised land elsewhere. According to History, that Zion was to be in the Great Salt Lake Valley, where Brigham Young brought 148 Mormons in 1847. At the time, the region was under the control of Mexico, though it would be ceded to the U.S. in 1848 (via Constituting America).

This rural valley did not shield Mormons from scrutiny for long. One religious doctrine elicited special horror: polygamy. PBS notes that polygamy may have been practiced by Joseph Smith in the 1830s, though he didn't mention this allegedly divine command until 1843. Mormons didn't publicly admit to it until 1852. Polygamy was only practiced by a minority of powerful church members, while many Mormons themselves pushed back against the practice.

All that mattered little to outsiders. Speaking to common sentiment, the Kansas Republican platform of 1856 referred to "those twin relics of barbarism — polygamy and slavery" as something elected officials would work to abolish in their territory. According to PBS, anti-polygamy laws were enacted on a federal level, spurred on by anti-Mormon media that breathlessly told of the evils of such unions. Ann Eliza Young, one of the ex-wives of Brigham Young, became especially notorious after a speaking tour and memoir purported to reveal the evils of Brigham Young's marriage situation. Ultimately, the LDS church bowed to pressure and effectively forbade members from practicing polygamy in 1890.

The Utah War almost broke into real action

Though many Mormons found some relief when they moved to Utah, such a big change didn't mean they were free from conflict forever. In fact, Utah would set the stage for what was very nearly the biggest Mormon war of all.

Though anti-Mormon sentiment certainly played into what became known as the Utah War, church president and territorial governor Brigham Young had his part, too. According to Smithsonian Magazine, he openly ran things in favor of Mormons, even though he and other church leaders had led the charge for Utah to become an official territory. Yet that set the stage for a series of clashes between federal officials and Mormon territorial officers, many of whom locked horns over the matter of polygamy. Young also hinted, sometimes quite strongly, that he didn't quite believe Mormons were to be Americans and thought that perhaps Utah should become its own nation.

By 1857, federal officials were alarmed by reports that Mormons had been courting Native American tribes in an allegiance against the U.S. LDS members were themselves rallying after rumors that the government was sending forces against them. In fact, President James Buchanan did send thousands of soldiers to the region from fall 1857 to spring 1858, as per Smithsonian Magazine. Outright war was avoided when Young agreed to step down as interim governor and Buchanan, facing public frustration with the expensive troop movements, pardoned all rebellious Mormons who agreed to abide by federal law.

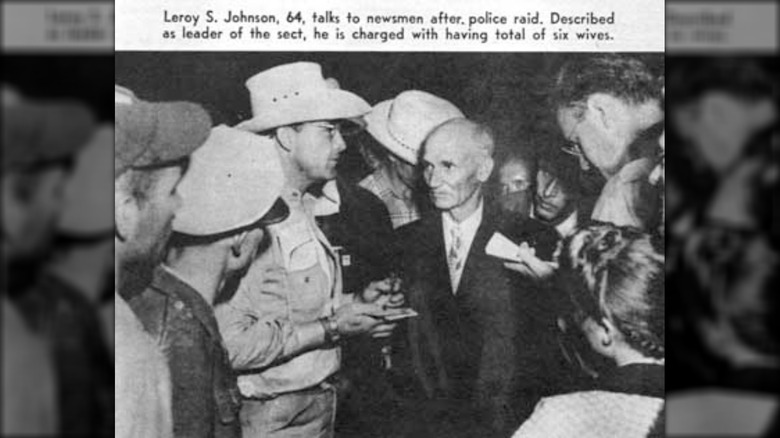

The Short Creek raid was pivotal for the FLDS

Though the LDS church stopped endorsing polygamy in 1890 and took it a step further by threatening ex-communication for the practice in 1904, that wasn't enough to deter some of the faithful. By that time, plural marriage had become an integral part of their faith and family structure, at least for some. The power of that tradition was so strong that they continued to take on multiple wives, despite opposition not only from the federal government, but their own church.

It got to such a point that groups began to break away from the mainstream LDS church, with one of the largest forming the Fundamentalist Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (FLDS). Beginning in the 1920s, some began settling in Short Creek, Arizona, hoping the rural surroundings would help them practice polygamy in peace.

Instead, the evening of July 26, 1953 saw state police descend upon the town, removing hundreds of Mormons from the settlement, including 263 children (via Los Angeles Times). Though local non-Mormons had earlier been upset about increased school taxes brought about in part by the large polygamist families, public opinion in the aftermath of the raid turned. Many who saw news reports of separated women and children felt sympathy for their plight. Members of the FLDS began nursing a grudge against the Gentile government that continues to the present day.

Mormons abroad may be targeted

Though much of the early history of Mormonism is focused in the United States, the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has nearly always been interested in converting others. For instance, the family of Utah Senator Mitt Romney first joined the faith in 1830s England, becoming some of the earliest foreign converts to Mormonism (via BBC). There are now about 53,000 full-time missionaries operating across the world.

However, safety isn't guaranteed for missionaries or local Mormons. Two missionaries were killed in Bolivia in 1989 by a leftist group that proclaimed war on all "Yankee invaders" (via The Washington Post). Then again, Deseret News claims that missionary deaths for the LDS church are very infrequent, breathless news reports notwithstanding.

More recently, Mormons in Mexico have faced increased scrutiny. According to The Conversation, polygamy-minded Mormons began moving to the country after the U.S. government and then the mainstream LDS church banned plural marriage. The LeBaron family became prominent and so became the targets of anti-Mormon attacks, which were partially motivated by their status as Americans (many LeBarons have dual U.S.-Mexico citizenship). Others talked of serious abuse being committed by family members in their enclave, Colonia LeBaron, while the family had already established its own history of violent attacks by some members. The family has also run afoul of drug traffickers, who appear to have been behind the brutal killings of three women and six children from the LeBaron and Langford families in 2019 (via BBC).

Anti-Mormon hate remains a modern problem

Lest you think anti-Mormonism is all in the past, just take a look at recent American politics. Mitt Romney's turn as the Republican presidential candidate in 2012 led to much hand-wringing over the place of Mormons in American society and politics. A large part of that had to do with lingering half-truths and misconceptions still held by modern non-Mormons, as Boston University Today reports. It goes far beyond whispers about temple undergarments and TV shows that purport to show polygamous families. Some still assume that Mormons are a massive voting bloc that's either too conservative for liberals or too boundary-pushing for conservative Christians. Others automatically assume that plural marriage is common practice when most Mormons would likely argue that it's a historical artifact treasured only by fringe groups.

All of those misunderstandings can be more than merely annoying. In fact, they sometimes lead to violence. According to Deseret News, anti-Mormon sentiment has been prevalent enough that the FBI has been tracking it for years in an effort to collect information about hate crimes against religious minorities. For 2017, the agency confirmed 15 anti-Mormon hate crimes. It's hardly the numbers faced by other groups, such as the 938 anti-Semitic crimes levied against Jewish people in the same year. Still, the fact that the crimes — which include offenses like vandalism, theft, and intimidation — are being committed against Mormons in the first place shows that anti-Mormonism is still active generations after Joseph Smith first made waves.