How Grave Robbing Led To The 1788 Doctors' Riot

For most of United States history, doctors and medical students who wanted to study a corpse went out and robbed graves in order to have dead bodies to dissect. And depending on the bodies that were taken, the authorities often turned a blind eye. Meanwhile, those who were body-snatching didn't think that they were doing anything wrong. At one point, when asked whether or not they were ashamed of themselves, some grave robbing medical students responded that they would do the same to their own grandparents and "think it no crime."

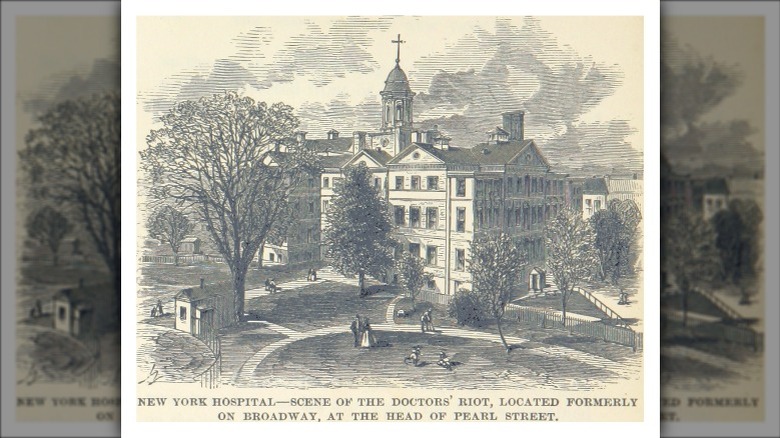

But in 1788, medical students in New York City saw the public turn on them as they crossed a classist and racist line. Known as the Doctors' Riot of 1788, the protest didn't actually involve rioting doctors. Instead, people turned on doctors and medical students to the point where some were run out of town.

After the Doctors' Riot, it took over half a century for laws to be enacted to dissuade grave robbing for medical research. But even then, those laws did little to curb the grave-robbing appetite of physicians and medical students. This is the story of how grave robbing led to the 1788 doctors' riot.

Cemeteries for enslaved and free Black people

During the 18th century, free and enslaved Black people in New York City were buried in a cemetery known as the Negroes Burial Ground. According to "Black Gotham" by Carla L. Peterson, the burial ground extended "from Broadway to Centre Street, and from Chamber Street north to Duane Street" and was in use after Trinity Church decided that Black people were no longer allowed to be buried in their cemetery in 1697.

The College of Physicians in Philadelphia writes that cemeteries of Black communities were often pillaged by doctors for bodies for dissections. And despite the fact that Black people made up only 15% of New York City's population in the 1780s, the vast majority of bodies used for dissections were those of Black people. And because the Negroes Burial Ground and the paupers' cemetery were close to New York City's only School of Medicine, they were a primary target for doctors, per The Lancet.

Although the burial grounds of poor white communities were also abused by grave robbers, burial grounds of Black communities were targeted because they were comparatively geographically isolated, and "the Black community tended to be poorer and lacked the social and moral protection that the white community was afforded." This also wasn't the only instance of physicians in the United States exploiting Black people for medical research. Half a century after the Doctors' Riot, J. Marion Simms became famous for experimenting on enslaved Black women for gynecological research.

Doctors and grave robbing

Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, grave robbing and body snatching were frequent occurrences in the medical community in both the United States and the United Kingdom. In the United Kingdom, a law was even passed by the end of the 1700s that allowed judges to sentence murders to death as well as dissection, according to The College of Physicians in Philadelphia.

The American College of Surgeons writes that after American independence, several American states also passed their own laws that allowed judges to sentence people to death and dissection. In Massachusetts, a law was passed that specifically targeted those who participated in duels. However, doctors needed such a steady supply of cadavers that waiting for people to be executed couldn't keep up with the demand.

According to JSTOR, doctors often hired professional grave robbers known as resurrectionists to do the dirty work for them. But after the American Revolution, American Heritage writes that medical schools got rid of the middleman and started stealing bodies themselves. And once medical students also started needing to do the dissections themselves, they were required to find their own bodies to dissect. "Each student was expected to obtain his own bodies to dissect, just as he was expected to obtain his own paper and quills and books." But while the doctors who grave robbed tried to leave as little trace as possible, the students were soon making little effort to cover their tracks, per The Lancet.

Freedmen notice the grave robbers

In 1788, Black families noticed the grave robbing that was occurring in their burial grounds and got together to petition city authorities to keep medical students from grave robbing. History of Yesterday reports that up to 3,000 Black people petitioned the Common Council on February 3, 1788, and asked them to intervene in the grave robbing that was occurring in their cemetery. According to "Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898" by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace, although the petitioners acknowledged that the use of cadavers was for medical research, they were horrified that the students would grave rob "without respect to age or sex, mangle their flesh out of a wanton curiosity and then expose it to beasts and birds."

Meanwhile, according to the New York African Burial Ground Archaeology Final Report, Black people started using a private cemetery made available to them by its owner Scipio Gray while they waited for the Common Council to act. But even there, their relatives weren't safe from grave robbers. In one instance, American Heritage writes that Gray was forced to stay inside "at the peril of his life" while the bodies of a child and elderly person were disinterred.

However, the authorities completely ignored the issue. The Lancet writes that as long as Black people and poor white people were targeted for grave robbing, "New Yorkers felt they could overlook the nocturnal activities of the resurrectionists." That is, until medical students started targeting the cemetery of Trinity Church.

Grave robbing Trinity Church

Before long, the medical students got overconfident, deciding to expand their grave robbing past the graves of Black people and poor white people, and they snatched a body from Trinity Church Cemetery. In response, a letter was printed in the Daily Advertiser on February 21, 1788, that described "the grave of a person recently interred in Trinity Churchyard was opened, and the Corpse, with part of the clothes, were carried off.—Any person who will discover the offenders, so that they may be convicted and brought to justice, will receive the above reward from the Corporation of the Trinity Church," per American Heritage.

A reward of $100 was offered, equivalent to over $3,000 in 2022, for information on the stolen body, according to "A Traffic of Dead Bodies" by Michael Sappol. The Daily Advertiser even started printing correspondences about the subject of grave robbery, "including a defiant and inflammatory letter by 'A Student of Physic.'"

Because some of the most respected and influential families in New York City were buried at the Trinity Church Cemetery, it was clear that the medical students had crossed a line. The New York Packet voiced this opinion clearly when it printed: "The interments not only of strangers, and the blacks had been disturbed, but the corpses of some respectable persons were removed," per Dissection and Discrimination by David C. Humphrey.

The waving arm

Around the middle of April 1788, a group of white children was playing outside a medical training school where Columbia University is now when they noticed a medical student named John Hicks Jr. dissecting a body. The American College of Surgeons writes that although accounts differ slightly, many claim that Hicks taunted one of the boys from the window by waving a dissected arm at them and claiming that it belonged to the boy's recently deceased mother. According to The Lancet, Hicks reportedly called out, "This is your mother's arm! I just dug it up!"

The boy's mother had, in fact, recently died, and when he ran home to tell his father what happened, his father gathered some friends and went to check on his wife's coffin. According to "Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898," the father found the wife's coffin was empty.

Regardless of whether or not Hicks had really taunted a boy with his own dead mother's arm, clearly, someone had indeed robbed her grave. New York Almanack writes that after finding the coffin empty, the father and his friends broke into the medical school, where they "found several bodies in various stage[s] of mutilation."

Rioting at the hospital

Upon discovering the half-dissected bodies in the hospital, the group of men removed the bodies from the hospital and displayed them publicly to a growing crowd. American Heritage writes that after bringing the bodies outside, they were piled into carts and burned in a bonfire. According to "A Traffic of Dead Bodies," the crowd outside the hospital proceeded to get larger and angrier until they all burst into the hospital. Once inside, more bodies were discovered that were so fresh that they were likely just dug up.

After making this discovery, the crowd proceeded to attack the medical students present. The crowd even took some of the men captive "until Mayor James Duane, the sheriff, and a group of prominent men succeeded in rescuing them" by arresting them and putting them in the jailhouse for their own safety. Meanwhile, one medical student managed to escape the sacking of the hospital.

That night, numerous doctors and medical students fled town to avoid the growing crowd. The Lancet writes that all the specimens at the hospital were destroyed by the crowd, and according to From Grave Robbing to Gifting, the laboratory was also burned down.

Hiding in the jailhouse

The following day, the crowd continued to hunt for doctors, medical students, and cadavers. And with several medical students still being held in the jailhouse for their own protection, a group of up to 400 people marched down Broadway towards the jail, writes Michael Sappol in "A Traffic of Dead Bodies." Although a number of people, including Governor George Clinton and Mayor Duane, stood between the crowd and the jail to try to dissuade the crowd. But the crowd only continued to grow until it numbered almost 5,000 people "carrying wooden staves, rocks, and now clubs."

After several hours, Governor Clinton finally ordered the militia to defend the jailhouse and between 50 to 150 armed men. And as the crowd started throwing bricks and stones at the militia, the militiamen opened fire on Mayor Duane's order and charged with their bayonets in response.

At least six people — three from the crowd and three militiamen — died in the ensuing struggle, and according to The Lancet, it's possible that up to 20 people died later from their wounds. And according to "Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898," what became known as the Doctors' Riot was unprecedented because "no colonial mayor or governor had ever ordered soldiers to open fire on a crowd." For several days, the militia continued to patrol the streets. But for many New Yorkers, their sympathies lay with the protesting citizens rather than the physicians and medical students.

Grave robbing trials

The jailhouse was so damaged that sixteen extra guards were brought in to keep imprisoned people in while repairs were done over the following three months.

In the aftermath of what became known as the Doctors' Riot, only a couple of medical students implicated in grave robbing were brought to trial. And George Swinney was seemingly the only medical student to be found guilty and sentenced for stealing the dead body of a white woman from the Trinity Church cemetery. Hicks would also be later indicted on four counts of body snatching, but "the grand jury mysteriously adjourned before his case could be heard," according to American Heritage. The remaining anatomy students and doctors in the New York Hospital building were kicked out and given a bill for damages that amounted to 22 pounds, 7 shillings, and 10 pence, equivalent to roughly $4,600 today.

"A Traffic of Dead Bodies" writes that although doctors and medical students continued to rob graves, they were "forced to become more discreet and to forgo indiscriminate plunder of graves." However, according to Dissection and Discrimination, grave robbers continued to empty up to 700 graves every year in New York City alone.

The bone bill

For the next 66 years, doctors and medical students continued to occasionally grave rob while they waited for people to be sentenced to death and dissection. But on April 3, 1854, An Act to Promote Medical Science and Protect Burial Grounds, also known as "The Bone Bill," was signed into law in the state of New York, which expanded the pool of cadavers that doctors were allowed to dissect.

According to "Bellevue" by David Oshinsky, the bill was proposed by New York University's John Draper, a British doctor who wanted to use dead bodies from prisons and almshouses in dissections, provided that they weren't picked up within 24 hours of death. "All vagrants dying, unclaimed, and without friends, are to be given to the institutions in which medicine and surgery are taught for dissection." But according to "A Traffic of Dead Bodies," the word almshouse was removed in the final version, "so that technically the unclaimed body of a rich person dying at home might be taken for dissection."

Ultimately with this bill, physicians were thus able to justify body snatching because it wouldn't technically be grave robbing if the bodies were not yet buried. And those who could afford to be buried in a cemetery were able to rest easy knowing that they could afford to rest in peace. And for most of the 19th century, the Bone Bill was poorly enforced, and "anatomy scandals proliferated" as the number of medical schools and medical students.

Long-lasting effects of the riot

By the start of the 20th century, the rest of the United States adopted anatomy laws similar to the one in New York, focusing on unclaimed bodies from morgues and charity hospitals. According to "The Poetics of Processing," edited by Anna J. Osterholtz, this created "a legalized and state-sanctioned tie between dissection and destitution." If a body was unclaimed or if the friends and family were too poor to pay for a burial, dissectionists could claim the body. As a result, many poor people began avoiding hospitals out of the fear that the doctors would experiment on them and try to induce death.

Humphrey also notes in Dissection and Discrimination that the laws didn't do much to stop grave robbing and body snatching. And "the illicit traffic in cadavers was a far-flung, interstate business."

"A Traffic of Dead Bodies" writes that in the South, dead bodies were also requisitioned from state prisons, which had disproportionately high populations of Black people and high mortality rates. When Johns Hopkins acquired 1,200 dead bodies in 1898, two-thirds were those of Black people. And when legal avenues failed, Northern medical schools would get Southern body snatchers to ship them the bodies of dead Black men.

Other anatomy riots

New York City wasn't the only place that experienced an anatomy riot related to dissection. According to the Science History Institute, 17 anatomy riots took place in the United States before the American Civil War, including in cities like Boston, Philadelphia, Baltimore, and St. Louis. The National Museum of Civil War Medicine writes that in almost all of them, the associated medical schools were sacked and destroyed.

In the United Kingdom, there was also the Brown Dog Affair of the 20th century, in which protests against vivisections of animals lasted seven years in London, England.

However, few doctors, medical students, or grave robbers faced any consequences for their actions. According to Smithsonian Magazine, when a grand jury indicted a medical student in 1880 who was found to have dug up and sold corpses from Baltimore to places like St Louis and Atlanta, the judge found the man innocent without a jury, ruling that "the testimony implicated Jensen in the affair, but it was not such as to warrant a verdict of guilt." In general, being involved with grave robbing had little-to-no negative impact on one's medical career.