The Tragic Tale Of The Ivory-Billed Woodpecker

Few birds conjure the strange mix of awe, sadness, and hope quite like the magnificent ivory-billed woodpecker. According to the Science History Institute, the sight of one was so astonishing that people apparently called out "Lord God, what a bird" when they first beheld one.

Indeed, as James T. Tanner — an ornithologist who studied the birds — notes in his book "The Ivory-billed Woodpecker," it was the biggest woodpecker in North America and the second largest in the world behind its cousin, the imperial woodpecker of Mexico. It was also a strikingly beautiful bird. According to Tanner, its mostly black plumage was glossy, tinged with purple iridescence, and marked by two white stripes. And then, of course, there was its massive namesake ivory-white bill.

The ivory-billed woodpecker has reached a near Bigfoot-level of mystique in recent years, as sightings are reported and just as quickly dismissed due to lack of evidence. Yet, people wonder: could this ghost bird still be out there? Birders, ornithologists, and locals alike have combed the swampy woodlands of its native southeastern United States for years, but there has not been a single undisputed sighting of the species since 1944 (per the American Bird Conservancy). While some hold out hope that it lives, many believe that this bird is long extinct. From over-collecting to widespread wartime logging to valiant-but-doomed efforts to save the species, here is the tragic tale of the ivory-billed woodpecker.

The ivory-billed woodpecker has always been hunted

Ivory-billed woodpeckers have always been in demand. According to James T. Tanner in his book "The Ivory-billed Woodpecker," Native Americans used bills and crests as decorations on peace pipes, coronets, and belts. Bills especially were highly sought after and were worth many valuable goods when traded. Woodpecker parts were also said to cure venereal diseases — the dried head of one could allegedly give a man strength in battle. As a result of such trading, ivory-billed woodpecker remains have been found far outside their natural range.

When European settlers arrived in North America, they considered this giant woodpecker the ultimate curiosity. According to John James Audubon in 1831 (via Tanner), 25 cents bought you two or three ivory-billed woodpecker heads at wooding places, which were basically gas stations for steamboats. In Florida, Tanner notes, bills often went for five dollars apiece — big money in the 1800s. Due to their impressive size and the bird's common name, many people mistakenly believed that they were made of real ivory. Either way, they made excellent watch charms.

Ivory-billed woodpeckers were also occasionally shot for their meat. While it's been claimed that some people considered them tastier than ducks, Tanner observed that, more often than not, the birds were shot for use as fish or trap bait. He felt it necessary to declare in his report for the species: "Rigid protection from man will be necessary for the continued existence of the Ivory-billed Woodpecker."

Ivory-billed woodpeckers were collector's items

As ivory-billed woodpeckers became increasingly rare, their value for specimen collectors skyrocketed. Ornithologist Dr. Jerry Jackson explained to New Orleans Public Radio that prepared specimens of rare birds were collectibles in the late 1800s, much like stamps and Beanie Babies in more modern times. In his book "The Ivory-billed Woodpecker," Tanner notes that taxidermists would often pay local hunters to find and shoot the birds for them.

By 1921 the species was so rare that many thought it was already extinct, per Audubon Magazine. But in 1924, Cornell ornithologist Arthur Allen miraculously located a nesting pair of ivory-billed woodpeckers in Florida. Not wanting to disturb the birds before they laid their eggs, he left the nest alone for several weeks. When he returned, he found both birds gone — they had been shot by local taxidermists. According to Audubon Magazine, the pair was likely sold to a Florida museum for $175 — a serious chunk of change back then.

It's a cruel twist of fate that already declining species become those most sought after by collectors. The same thing happened with the Great Auk — in fact, the very last pair on Earth was strangled by collectors and sold to a museum (per Alfred Newton in "Mr. J. Wolley's Research in Iceland respecting the Gare-fowl or Great Auk"). According to a 2007 study published in The Auk, there are 413 ivory-billed woodpecker specimens in institutions worldwide.

Logging made the species an unintentional casualty of war

The ivory-billed woodpecker required large areas of mature, virgin forest to survive, per James T. Tanner in his book "The Ivory-billed Woodpecker." But virgin forests were being stripped away at an alarming rate in 1800s America. According to the National Humanities Center, logging intensified in the South following the Civil War. Hundreds of thousands of trees were felled during the war and, in its aftermath, more were logged to build railroads, while swamp forests around the Mississippi Delta were then cleared to make way for agriculture. When it was all said and done, around 90 million acres of forest were logged in the South, leaving just 3 million intact (per the Science History Institute).

According to the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, the species originally lived in upland pine forests but had retreated to the swamps by 1891. Unfortunately, it didn't fare much better there. As Tanner notes, the disappearance of ivory-billed woodpeckers in Missouri, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida coincided with periods of intense logging. He observed that by 1915 they were gone from Mississippi, Alabama, Arkansas, and Texas, and mostly gone from South Carolina, Florida, and Georgia. Things didn't get any better for the birds: Logging increased even more during World War I and World War II, destroying most of the species' remaining habitat (per the Cornell Lab of Ornithology).

Several biological factors were working against the species

In addition to the devastating impacts of hunting, collecting, and logging, the ivory-billed woodpecker's own biology was working against it. James T. Tanner's research, presented in his book "The Ivory-billed Woodpecker," revealed that the species was never common. Even in optimal forest habitat, he estimated that a single pair required at least two and a half to three square miles of forest to survive.

Tanner also observed that the birds traveled great distances each day to find enough of their preferred food — wood-boring beetle larvae — which could only be found in standing dead trees. Therefore, in order for the ivory-billed woodpeckers to survive, they needed areas of forest large enough to support many stands of dead trees. Because wood-boring beetle larvae were the species' main food source, and they could only be found in a very specific and limited habitat, the ivory-billed woodpecker can be considered a specialist species (per Britannica). According to a 2011 study published by The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (Tübitak), this puts such a species at a greater risk for extinction.

To make matters worse, Tanner noted that ivory-billed woodpeckers frequently only raised one or two chicks per year. Per the Tübitak study, low reproduction potential is another factor that increases a species' likelihood of extinction. In fact, of the eight attributes shared by extinction-prone species — of which only one is needed to qualify — the ivory-billed woodpecker demonstrated seven.

Heroic efforts to save the last known population failed

In 1937, budding ornithologist James Tanner was tasked with studying the nearly-extinct ivory-billed woodpecker (per James T. Tanner in "The Ivory-billed Woodpecker"). He focused his research on the last known dozen living in an 80,000-acre tract of mostly untouched forest in Louisiana, owned by the Singer Sewing Machine Company. But Singer had sold the logging rights to the land, prompting Tanner to write an urgent report.

According to the Science History Institute, the influential Richard Pough — future president of The Nature Conservancy — crafted a plan to buy the Singer Tract and turn it into a nature preserve. When Pough approached the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company — who owned logging rights to most of the tract — in 1942, they were surprisingly eager to sell it. Negotiations were in the works to buy the tract for $200,000 — which is around $3.6 million as of 2022.

Miraculously, Pough rounded up the money and returned to finalize the deal, but the company had changed its mind. Around 500 Nazi war prisoners had been recently shipped to Louisiana, giving the lumber company a free workforce. James Griswold, the owner of the Chicago Mill and Lumber Company, was unapologetic, telling Pough: "We're just money grubbers. We're not concerned with ethical considerations" (per the Science History Institute). The Singer Tract was logged to the ground over the next few years and, after the war, most of the wood was used to make tea chests for the British — which even the Nazis cutting the trees found ridiculous.

The last living ivory-billed woodpecker was painted moments before her death

In April 1944, as logging continued, the National Audubon Society hired bird artist Don Eckelberry to paint the last known living ivory-billed woodpecker, (per Tim Gallagher in his book "The Grail Bird"). According to the Science History Institute, the last bird was a female, and she spent her final days living alone in a small grove of trees, surrounded by the stump wasteland left by the logging crews. As promised, Eckelberry observed, sketched, and painted the woodpecker. In fact, he stayed until he heard the German loggers approaching, leaving minutes before her grove was felled.

As Michigan Quarterly Report details, the 23-year-old Eckelberry followed the last ivory-billed woodpecker for two weeks, jotting down everything he saw in his notes. He described hearing the species' characteristic double-note bill knock and watching her fly out and swoop gracefully onto a tree, noting her vitality. One of his paintings depicts the lonely flight of the single black-crested female woodpecker through a forest of stumps. In a poem included with his artwork, Eckelberry wrote: "Mostly we are preserved in life before our time, glazed, pickled, set in amber, and casketed above the ground." His observations and paintings became the last undisputed record of a living ivory-billed woodpecker in the United States (per the American Bird Conservancy).

The species was rediscovered in Cuba – and lost just as quickly

While the North American ivory-billed woodpecker faced extinction due to logging, its Cuban cousin was meeting a similar fate. The birds were driven out of their preferred habitat as the land was converted to farmland, but some were able to survive in the rugged inaccessible mountain forests. A study published in The Auk details a successful 1948 mission that revealed a few living woodpeckers.

The study inspired American ornithologists to keep looking. According to Phillip Hoose in his book "The Race to Save the Lord God Bird," biologist George Lamb discovered 13 ivory-billed woodpeckers alive and well in the mountains of Cuba in 1957. Since the land was owned by U.S. corporations, Lamb had high hopes of creating a preserve to protect the birds. But local politics again interfered with the species' survival. Per Britannica, Fidel Castro took control of Cuba in 1959, and the complicated nature of the Cuban Revolution hindered contact between the U.S. and Cuba.

Per The New York Times, Cuban biologists Giraldo Alayón and Alberto Estrada located a female ivory-billed woodpecker in 1986, and a month later, another expedition revealed at least one male and one female woodpecker. The rediscovery ignited hope that the species could be re-established in Cuba and even North America. Sadly, the excitement was short-lived. According to a 1995 study published in Bird Conservation International, the Cuban ivory-billed woodpecker was last seen in 1987. An extensive search in 1993 turned up no birds, and the study alleges that the subspecies likely went extinct around 1989 or 1990.

A 2004 sighting in Arkansas caused a war in the birding community

In 2004, the unthinkable happened: the ivory-billed woodpecker returned from the dead, 60 years after it was last seen alive — or so some desperately wanted to believe. According to the University of Arkansas at Little Rock, it all began when a kayaker thought he saw the bird in the Big Woods of Arkansas and cryptically mentioned it online, prompting David Luneau to go out in his canoe with a camera. Little did he know that the four-second video he captured of a flying woodpecker would become, per NPR, "the Zapruder film of the birding world."

John W. Fitzpatrick — the then-director of the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology — was so convinced by the video footage that he and his team published a 2005 article in Science announcing the species' return. But other big names in the bird world did not agree with this assessment. The renowned ornithologist David A. Sibley claimed that the video shows a pileated woodpecker (pictured), a similar but not extinct species (per NPR). He published a 2006 rebuttal to Fitzpatrick's article in Science. Undeterred, Fitzpatrick then published a 2006 rebuttal of Sibley's rebuttal, also in Science, insisting that the bird in the video is definitely an ivory-billed woodpecker.

While the debate has still not been settled, an obvious fact remains: no definitive evidence of an ivory-billed woodpecker has been found in recent decades. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (via BirdWatching), federal and state governments have spent over $20.3 million on attempts to reveal the ivory-billed woodpecker, yet years of exhaustive searches have yielded nothing.

The ivory-billed woodpecker may be officially declared extinct in 2023

In September 2021, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) proposed delisting the ivory-billed woodpecker from the Endangered Species Act's protection, citing its apparent lack of existence. The proposal was met with an intense mix of emotions from the bird world (per BirdWatching) — some were outraged, and others agreed that the time had come to admit that the "Lord God bird" is gone. But such a decision goes beyond mere bureaucracy and strong opinions: If a species is delisted from the Endangered Species Act, it also loses its legal protection, and if any endangered woodpeckers are still alive out there, they desperately need it.

According to Reuters, the USFWS — following an initial six-month comment period and review — agreed to hold off on declaring the species extinct in July 2022. The final decision was originally scheduled for September 2022 but was pushed back to March 2023, giving the ivory-billed woodpecker six more months as a critically endangered — but possibly alive — species. Public comments were also reopened in the hopes that compelling video or photographic proof of the bird turns up. Another review period will follow before the species is officially declared extinct. "It's a beautiful bird, and no one wants it extinct," USFWS spokesperson Ian Fischer told Reuters, "But we need evidence."

Forests suffer in the ivory-billed woodpecker's absence

The ivory-billed woodpecker, like most woodpeckers, was a keystone species (per Audubon Magazine). That is, its presence had a disproportionately large effect on the biological community in which it lived (per Britannica). A keystone species gives its community structure — just like the stone that it is named for supports the arch of a bridge. Removing such a species can therefore have unexpected impacts on the other plants and animals living around it.

According to James Tanner (via the Science History Institute), ivory-billed woodpeckers created large holes in dead trees while foraging for beetle larvae, allowing other insects to access the inner wood. This sped up the trees' decay and caused them to fall, which opened up small pockets of sunlight in the woods. Such clearings are crucial to the health and longevity of a forest, as they allow young trees to get enough light to grow up and fill the spaces.

In his book "The Ivory-billed Woodpecker," James T. Tanner also notes that the ivory-billed woodpecker was the only species with a bill powerful enough to strip the bark of tightly wound trees. For this reason, it was likely the only animal able to prey on long-horned beetle larvae and therefore prevented catastrophic outbreaks of this wood-boring beetle, which is capable of killing large sections of forest.

We probably can't clone the ivory-billed woodpecker

In 2020, a black-footed ferret — an endangered mammal — was successfully cloned (per Audubon Magazine). This gave conservationists hope that they could do the same thing with other imperiled species, like the ivory-billed woodpecker. But, according to Audubon Magazine, cloning works — or rather doesn't — a little differently in birds. Because birds lay eggs, the egg cell nucleus — which contains the DNA required for cloning — is surrounded by a large yolk. This makes traditional cloning, in which DNA is swapped from one nucleus to another under a microscope, dang-near impossible.

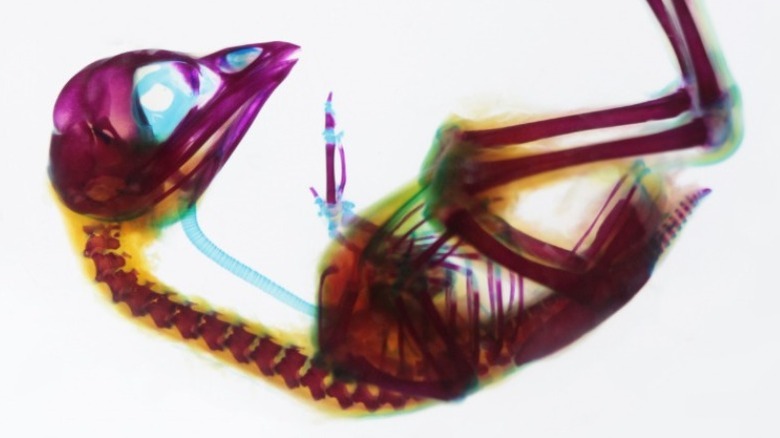

There is another option, though the science isn't all the way there yet for extinct species. The cells that give rise to a bird's gonads can be cloned and implanted into a developing embryo of another bird species, resulting in what scientists call a chimera (per Audubon Magazine). This technique has been used to create male domestic chickens that produce the sperm of another species. You would, of course, then need to mate this male chimera to a female of the desired species for it to work. So far, this method has been successful in producing rare birds like houbara bustards.

According to Scientific American, scientist Ben Novak hopes to one day use this method to resurrect the extinct passenger pigeon. But without parents of its species to raise it, the question remains whether this bird would act like a passenger pigeon — and the same applies to any other extinct species that may end up as candidates for resurrection, including the ivory-billed woodpecker.