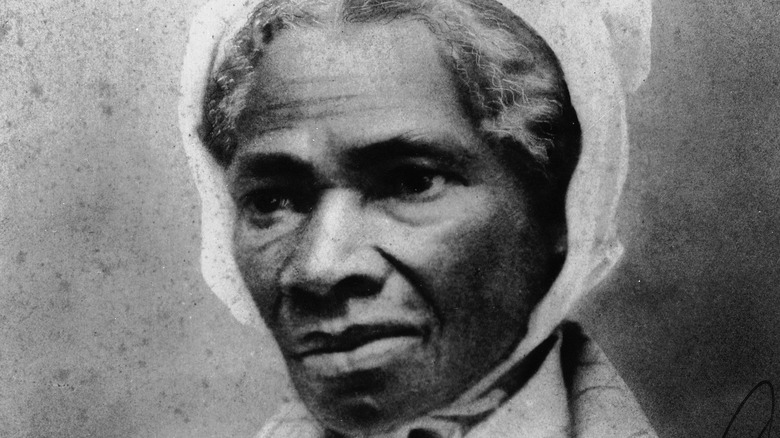

Inside The Time Sojourner Truth Was Acquitted Of Murder

Sojourner Truth was a women's rights activist born into slavery as Isabella Baumfree around 1797. Colonel Hardenbergh owned her family and when he died, their ownership was transferred to his son, Charles. In 1806, Charles died and the Baumfrees were separated. At 9 years old, Isabella was bought by a man named John Neely for $100 and a flock of sheep. As noted by History, she was subjected to harsh punishments and physical labor. Isabella was sold a couple more times and at 13 years old, she was living in West Park, New York with the Dumonts.

Isabella was forced to marry Thomas, a fellow enslaved person owned by Dumont, when she was 18 years old, and together, they had five children. In 1817, the New York legislature ended slavery in the state and declared July 4, 1827, as the final date of the emancipation of slaves (via Historical Society of the New York Courts). Dumont told Isabella that she would be freed one year before the date, but when the time came, Dumont refused to free her. This led Isabella to run away with her baby, while she left her other children behind.

Isabella Baumfree's freedom

Isabella Baumfree headed to New Paltz, New York, where she and her daughter were taken in by Isaac and Maria Van Wagenen, a couple who owned a farm. According to American History Central, Dumont found out Baumfree's whereabouts and attempted to get her back, but the Van Wagenens brokered a deal with him; they promised to pay Dumont $20 until she was emancipated in 1827.

Baumfree lived with the Van Wagenens a couple of years after her emancipation, and she changed her name to Isabella Van Wagenen. While there, she found out that Dumont illegally sold one of her children, 5-year-old Peter. The Van Wagenens helped her to get him back by filing a lawsuit against Dumont, and fortunately, she won. As noted by History, it was the first instance where a Black woman sued a white man in court and ended up winning the case. The Van Wagenens treated Isabella well. They asked her to call them by their first names instead of "master" and "mistress," and it was also during her time living with them when she practiced Christianity. In 1829, she moved to New York City where she found employment as a housekeeper for Elijah Pierson, an evangelist preacher.

The death of Elijah Pierson

Elijah Pierson was a businessman and preacher and together with a man named Robert Matthews, they claimed to be oracles. They called themselves "The Prophet Matthias" and "Elijah the Tishbite," respectively (via the New York Almanack). Pierson and Matthews formed their own independent church that they called "The Kingdom," and Isabella Van Wagenen became a housekeeper for Pierson, and later on, for Matthews.

In July 1834, Pierson fell ill after eating blackberries. Matthews forbade medical intervention, and Pierson, too, was adamant that he would get better from his illness through prayers. He endured bouts of vomiting and after a few days, he was dead. An autopsy performed by two doctors revealed that Pierson died of poisoning, and Matthews was accused of murder as well as theft. Benjamin Folger, who was one of Pierson's wealthy followers, also accused Van Wagenen of the crime, claiming that she once attempted to poison him and his family. It was a ruse to shift attention from Matthews, as he believed that the jury wouldn't side with a Black woman.

She was acquitted of murder

Having prior experience in court, Isabella Van Wagenen knew what to expect. She fought the charges against her in court, and much to Benjamin Folger's surprise, she won the case and was acquitted of theft and the murder of Elijah Pierson. As noted by the New York Almanack, Van Wagenen filed a libel suit against Folger, and she won that case as well. The court ordered Folger to pay $125 to her as a result. After Pierson's death, The Kingdom collapsed.

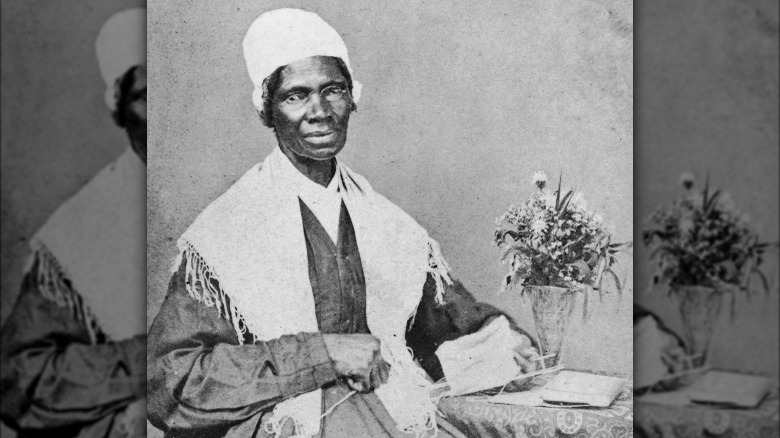

Van Wagenen decided to live her life as a traveling preacher, and in 1843, she joined the Methodist Church and changed her name to Sojourner Truth. According to the Library of Congress, she chose the name "Sojourner because I was to travel up and down the land showing people their sins and being a sign to them, and Truth because I was to declare the truth unto the people."

Life as an activist

In 1844, Sojourner Truth was in Massachusetts when she joined the Northampton Association of Education and Industry, an abolitionist organization. According to Women in History Ohio, the group had about 200 members who lived together on farmland. There, she was able to work with other known abolitionists including David Ruggles, Frederick Douglass, and William Lloyd Garrison. The community was self-sustaining, but just two years later, the group disbanded.

Thereafter, Truth continued her activism work and toured with her fellow abolitionists to give speeches about human rights and slavery. She was encouraged to share her experiences as an abolitionist and slave via a memoir, but Truth never learned to read and write. What she did instead was to dictate her accounts to Olive Gilbert, and they were compiled in a manuscript titled "Narrative of Sojourner Truth, a Northern Slave, Emancipated from Bodily Servitude by the State of New York, in 1828," which was first published in 1850, as noted by American History Central.

Sojourner Truth's legacy

In 1951, Sojourner Truth began touring once again. It was in that year when she delivered her famous speech titled "Ain't I a Woman?" at the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio. She drew large audiences as her popularity grew, and she rose to prominence as an equal rights icon. During the Civil War, Truth helped recruit troops for the Union Army. At one point, she had a meeting with President Abraham Lincoln to talk about her experiences.

Truth remained an activist until the end of her life. In the late 1860s, she moved to Battle Creek, Michigan, where some of her children resided. As reported by History, Truth died in her home on November 26, 1883. In 2009, a bronze bust of Truth was unveiled in 2009 at the Emancipation Hall of the Capitol Visitor Center in Washington, D.C. It was the first sculpture displayed in the United States Capitol in honor of an African American woman. In 2014, the Smithsonian Magazine named Truth as one of the "Most Significant Americans of All Time."