The Deadliest Hotel Fires In History

Mankind's ability to harness and manipulate fire has been central to its success. Sustenance, comfort, metalwork, bridges, engines, skyscrapers, computers, smartphones – these are all, in part or in whole, derived from fire. Yet our cultivation of fire has not eliminated its danger. In recent years, there has been much attention paid to various wildfires, namely those in Australia and the United States, which have been recorded in terrifying first-hand accounts, such as this dashcam video taken in Glacier National Park. However, as devastating as wildfires can be, urban infernos might be even more terrifying, especially those that occur in large buildings with myriad hallways and crowds of panicked occupants.

Hotel fires have occurred all over the world, yet for reasons that aren't immediately clear, the United States has experienced many of the deadliest ones. So, from Spain and Russia to Milwaukee and New York City, here are the deadliest hotel fires in history.

1938 Terminal Hotel fire, 34 deaths

On May 16, 1938, an intense fire spread through the Terminal Hotel in Atlanta, Georgia, killing 34 people and injuring many more. According to the Digital Library of Georgia, the fire started with an explosion in either the basement or kitchen. The alarms were sounded in haste, but the flames were quicker. Just minutes after the emergency response had mobilized, the entire five-story building was ablaze, billowing smoke into the night sky. Then, as fire crews arrived, the roof collapsed, hindering their rescue efforts and sealing the fate of many trapped inside (via "Atlanta: Unforgettable Images of an All-American City").

The City of Atlanta notes that the Terminal Hotel, which was located on the northeast corner of Mitchell and Madison, was replaced by a one-story building later the same year. The tragedy at the Terminal would be Atlanta's deadliest hotel fire until the Winecoff Hotel fire of 1946.

1934 Kerns Hotel fire, 34 deaths

"The only reason I'm alive now," said Michigan House Representative John Dykstra, "is that I spent so much time in the hotel that I knew every turn in its corridors." Seven of Dykstra's fellow Michigan legislators were not so lucky. They perished along with 27 others during the Kerns Hotel fire, which raged in Michigan's state capital of Lansing on December 11, 1934.

The alarm was sounded at around 5:30 AM when "Pop" Hayhoe, the night janitor of the nearby State Journal building, saw flames in the hotel's windows (via Capital Area District Library). As Hayhoe completed his call to the fire department, he heard the first screams. Over the next two hours, fire crews worked tirelessly to contain the fire as guests, trapped in the wood-clad rooms and corridors, lept from the windows. One of them landed on a firefighter and broke the man's back, yet he continued to fight the blaze and look for survivors.

When the fire was contained at 7:30 AM, the scale of the disaster became clearer: 34 people were dead and 44 were injured, victims of a discarded cigarette.

1986 Siddharth Continental fire, 38 deaths

In the small hours of January 23, 1986, the banquet basement of the Siddharth Continental erupted into flames that rose through several floors of the building, killing 38 people (via LA Times). A 5-star hotel, the Siddharth was popular with international clientele, and this was reflected in the grim death toll. French, Britons, Argentines, Japanese, Americans, and Russians were all among the dead.

"We found bodies on every floor," a police officer said, "Some of them were in their beds, others in the hallway." Most of the dead had succumbed to smoke inhalation and had no doubt been panicking in response to the dismal emergency response. For example, the lighting system was quick to fail and was not corrected by the backup generator, which never activated. Guests were therefore plunged into darkness as smoke filled their rooms and their lungs (via India Today). "Anywhere in the world, you will find good hotels having separate power supply system for the fire alarms," one firefighter observed, "... there was none here. There wasn't even an internal public address system on which we could tell the inmates what precautions to take."

Speculation abounded on the fire's cause. The hotel's general manager believed it to be sabotage, as did the building's architect. However, a more credible explanation was given by the fire brigade, who suggested that there may have been a leak in the banquet area's gas cylinders.

1977 Hotel Rossiya fire, 45 deaths

With over 5,000 bedrooms, Moscow's Hotel Rossiya was the largest hotel in the world when it opened in the late 1960s. It held this record until 1993, when the new MGM Grand opened (via Bridge to Moscow). On February 25, 1977, a fire started, and, even in a building of this immense size, it covered ground with terrifying speed. The New York Times reported how the flames climbed from the fifth floor all the way to the hotel's 12th and final story, devastating everything in its path.

A dramatic scene unfolded as Soviet firefighters fought the blaze for some 6 hours, scaling ladders and directing water cannons as the inferno burst through window panes with relentless force. It wasn't until 3 AM that the fire was finally tamed.

The carnage was blamed on an elevator fault, but the truth of this is dubious, as the Soviet Union engaged in obfuscation and outright media blackouts. Indeed, the state news made no mention of the crisis in the next day's news cycle, despite it being one of the worst fires in Moscow's history.

1943 Gulf Hotel fire, 55 deaths

On September 7, 1943, there were 133 guests staying at the Gulf Hotel, a budget, male-only establishment in downtown Houston, Texas. According to KPRC 2, guests paid just 40 cents a night for a room and could pay another 20 cents for a cot, if necessary. These low fees may have bought a degree of comfort, but they did not buy safety, as the Gulf's 87 beds were partitioned not by walls but by oiled wooden panels, meaning the three-story building was one giant tinderbox.

The Houston Post and Houston Chronicle reported on how the crisis was almost averted. Alerted by the smell of smoke, a night porter followed the scent to room 201, where he found a smoldering bed sheet and mattress. A small fire, the porter extinguished the flames and discarded the linen in a closet. However, the fire had not been fully extinguished, and the closet contained solvents, mops, and other flammable materials.

Within an hour, the fire had returned with terrible vigor, combusting the wood paneling with shocking speed. "It was horrible!" said an assistant fire chief, "It was the most horrible thing I've seen." The men, many of them in their 60s and 70s, had little chance of escape as the flames and smoke consumed them. The Gulf Hotel fire remains the deadliest fire in Houston's history.

1946 La Salle Hotel fire, 61 deaths

Built between 1908 and 1909, the La Salle Hotel was described as the "largest, safest, and modern hotel west of New York City" (via Chicago Tribune). This claim would be fatally undermined on June 5, 1946, when a fire tore through the building, killing 61 people.

The fire began at around 12:30 AM in the hotel's Silver Grill Cocktail Lounge, and, as is usual, the flames spread at a lethal pace. The Tribune quoted a witness who spoke of a "hellish ball of fire" that destroyed the mezzanine and flooded rooms and corridors with smoke.

Like the Gulf Hotel fire, the La Salle had varnished wood paneling that accelerated the blaze, suffocating dozens with noxious fumes. "Many people overcome on the fourth floor," said D. S. Taggart, a salesman from Massachusetts, "Two men were lying outside my door. Another man and I dragged them into my room. We dropped a note down to firemen, who came up and took them down."

1979 Hotel Corona de Aragon fire, 72 deaths

On July 12, 1979, an explosion occurred in the ground floor cafe of the Hotel Corona de Aragon, a luxury hotel in Saragossa, Spain. The ensuing fire wreaked havoc, killing 72 people in what became Spain's deadliest hotel fire (via New York Times).

The fire occurred after a string of bomb attacks by ETA, a separatist group that was fighting for Basque independence. ETA bombed several hotels that summer but had alerted authorities before detonation, allowing guests to evacuate. This caused Governor Francisco Laina to reject the ETA speculation and conclude that the explosion was caused by a churros machine full of boiling cooking oil. The smoke caused by this vicious blast was sucked into the hotel's ventilation system, causing approximately half of the fatalities.

Helicopters from a nearby U.S. base launched a daring rescue mission, which included one chopper lowering Staff Sergeant Charles Hart onto the roof in a basket, which Hart used to save two guests while he remained on the rooftop until the aircraft returned. Also rescued was Carmen Polo de Franco, the widow of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco.

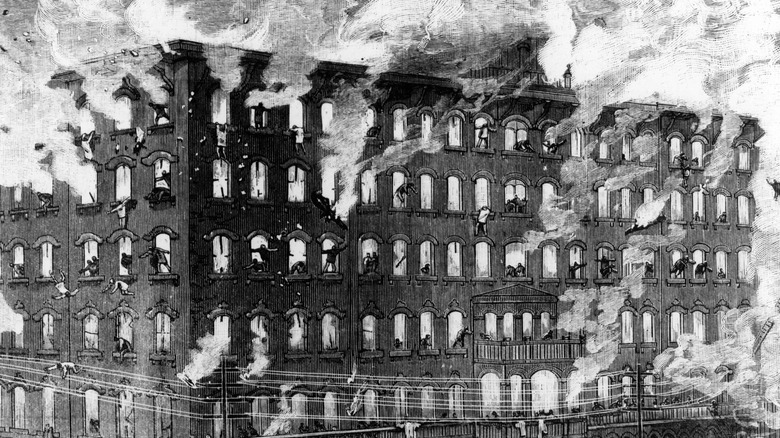

1883 Newhall House Hotel fire, 76 deaths

The Milwaukee fire department had long been wary of the Newhall House Hotel's fire safety when flames were seen bursting from the hotel's roof in the early morning hours of January 10, 1883 (via Wisconsin History). Firefighter Sam McDowell remembered the dire scene, "By the time we reached the hotel, the building was like a flaming strawstack. Men and women could be seen at their windows, shouting for help, screaming in despair."

The fire originated in the wooden elevator shaft, which allowed the blaze to race upwards and burst through the building floor by floor. Guests were burned and knocked unconscious by the smoke. Others fell to their death, unable to bear the heat. But many were saved, including General Tom Thumb and his wife Lavinia Warren, a famous dwarf couple who performed in P.T. Barnum's circus. Their size may well have saved their lives, as a fireman named O'Brien was able to carry both of them under one arm as he used his other to steady the swaying ladder.

Despite the fire department's heroic efforts, the Newhall House fire was and remains the worst blaze in Milwaukee's history, killing at least 76 people (via Encylopedia of Milwaukee).

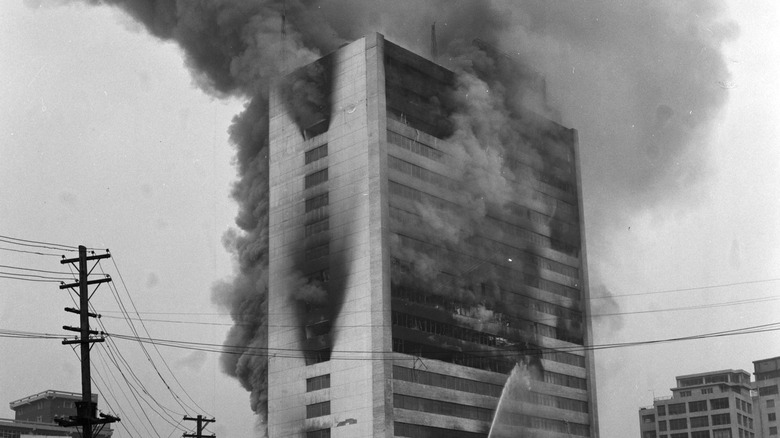

1980 MGM Grand fire, 85 deaths

"It was hell on Earth," said Robert List (via Review-Journal/NGA), Nevada's governor from 1979 to 1983, "[it's] etched into my memory ... that terrible smell and the blackness without color ... the bodies that were there. It was awful." List was surveying the floor of the MGM Grand, which had just suffered one of the worst hotel fires in American history. And like with other lethal fires, the cause was sickeningly preventable. A Clark County investigation determined that the blaze, which killed 85 people, was caused by faulty wiring in the casino's deli.

First responders remembered a terrible scene. City volunteer Joe Castiglia said, "Carrying people up to the roof was an experience I'll never forget ... The people we were taking up there were dead, were bodies." Most of these victims died from smoke inhalation that spread through the hotel's ventilation system. "Their faces were blackened around the nose where they would be breathing up the fumes and everything else," Castiglia added.

When the tragedy was over, the lawsuits began. Over 1,350 legal claims were made, and some $223 million was shelled out in a wave of litigation that attracted outside attorneys who grew the legal community of southern Nevada. State and county legislators made sweeping changes, too. All hotels and high-rises are required to have sprinkler systems, smoke detectors, and exit maps in every room.

1899 Windsor Hotel fire, 86 deaths

Built in 1873, the Windsor Hotel occupied a prized stretch of real estate between 46th and 47th Streets on Manhattan's Fifth Avenue (via New York Times). By the 1890s, the Windsor Hotel was described as "the most comfortable and homelike hotel in New York." However, nine years later, the Windsor would be a smoldering wreck that had claimed 86 lives.

According to City Journal, the fire broke out at around 3 PM on St. Patrick's Day, March 17, 1899. As nearby streets thronged with festivities, the fire spread through the brownstone building, consuming it. By 3:40 PM, the vast front wall collapsed. 50 minutes later, almost the whole structure had crumbled into flaming pile of rubble, trapping dozens of people.

The Victorian newspapers did not have the filter of the contemporary press. The New York Times wrote of headless bodies and described many of the victims as merely "ghastly fragments," such was the horrifying force of the fire and the building's collapse.

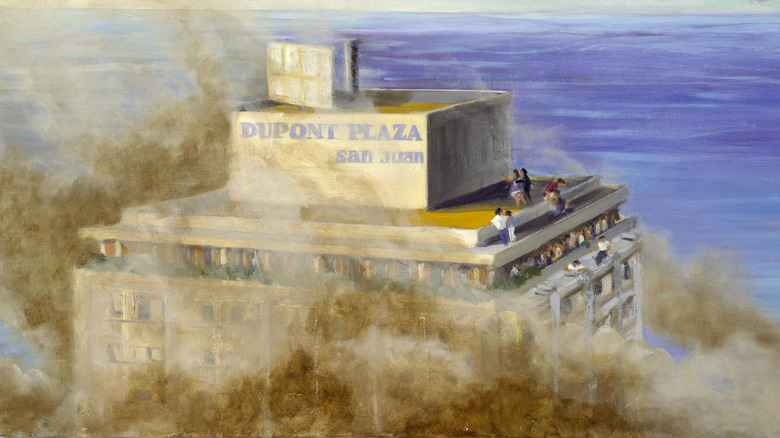

1986 Dupont Plaza Hotel arson, 98 deaths

On the afternoon of December 31, 1986, a fire started in the ballroom of the Dupont Plaza Hotel and spread through to the lobby and casino, killing 98 people (via NIST). It remains the worst hotel fire in the history of San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Connecticut florist Nick Perrotti told the LA Times of vivid nightmares that haunted him in his hospital bed. Perrotti broke his back, leg, and pelvis. He also lacerated his face and hands with broken glass. Yet the New Haven native was one of the lucky ones – his friends Linda Berkowski, Al Cohen, Susan Lawrence, and Bob Melillo all died in the tragedy. Disturbingly, NIST reported that badly burned victims did not have a lethal amount of carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide in their blood, which means they were likely killed by agonizingly severe burns rather than smoke inhalation.

Unlike the banal causes of many fires, such as the faulty wiring at the MGM Grand or the discarded cigarette at the Kerns Hotel, the tragedy at the Dupont Plaza was an act of arson. "We expect there may be arson here," said Governor Rafael Hernandez Colon, who was referring to the aggressive negotiations between the hotel and a labor union. Soon, disgruntled worker Hector Escudero Aponte admitted to setting fire, and on June 23, 1987, the New York Times reported that he was sentenced to two concurrent 99-year terms. Accomplices Jose Francisco Rivera Lopez and Armando Jimenez Rivera were sentenced to 99 years and 75 years, respectively.

1946 Winecoff Hotel fire, 119 deaths

On December 7, 1946, a fire broke out at the Winecoff Hotel in Atlanta, Georgia, killing 119 people (via NFPA). It remains the deadliest hotel fire in American history. According to Firehouse, the fire started on the third floor at around 3:42 AM, although the exact cause remains undetermined. What is perfectly clear, however, is that the Winecoff was not equipped to deal with a major fire. Fox 5 wrote that the hotel had just one staircase traversing the building's 15 floors. Furthermore, it had neither fire escapes nor sprinklers, and there had been no plans to install them, either, as recent fire code changes did not apply to older buildings (via Atlanta).

Many personal tragedies happened that night. One man jumped from the building with his son held tight against his chest. The father was aiming for a life net that had been erected by the fire department. The boy survived the fall, but his father died when he landed head first on the net's rim.

The most famous victim of the disaster was Daisy McCumber, who became the subject of a Pulitzer Prize-winning photograph taken by Arnold Hardy. As seen above, McCumber was captured in mid-air as she neared the end of her 11-story jump. Remarkably, the 41-year-old secretary survived, but not without great suffering. She broke her back, pelvis, and both legs, one of which she lost after seven operations.

1971 Daeyeonggak Hotel fire, 164 deaths

The United States may be overrepresented in the history of deadliest hotel fires, but the deadliest to date occurred at the Daeyeonggak Hotel in Seoul, South Korea. The fire began on Christmas day, 1971, and it was caused by a gas canister explosion in the second-story coffee shop, according to the New York Times.

The flames engulfed the whole building within just half an hour and raged for a further eight hours, killing dozens of victims, who were either suffocated, burned, or forced to jump to their deaths. All of this terrible suffering was exacerbated by lamentable safety protocols. The walls were not fire resistant, and the building's two staircases were not designed as fire escapes, causing them to fill with smoke and become giant chimneys (via Coopers). Furthermore, a police representative said that the city of Seoul lacked the equipment to fight such blazes.

Like during the fire at Hotel Corona de Aragon some eight years later, nearby U.S. military bases mobilized air power in an attempt to rescue guests. Helicopter crews were able to save eight people from the Daeyeonggak's roof before returning to base. Further efforts were hampered by both the thick, billowing smoke and the roof's design, which did not allow for helicopter landings.