Why Scientists Are Still Fascinated By Phineas Gage

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

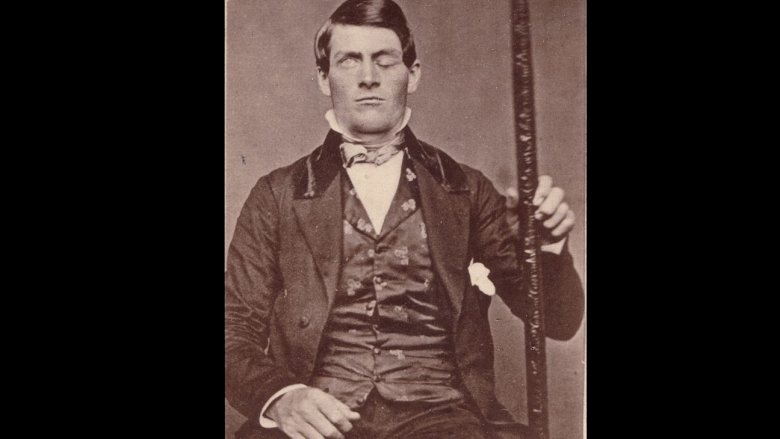

In the grand scheme of things, there aren't many ordinary, everyday people who have names remembered by historians, psychologists, and medical professionals alike. Unless, that is, something extraordinary happens to them. The extraordinary certainly happened to Phineas Gage on September 13, 1848. Unfortunately for Gage, the powers-that-be decided to go with the sort of extraordinary that could also be called "gruesome" or "horrific." He's still studied today; we haven't figured out just what happened to him, so we've even kept his skull around for reference.

Who was he, and what happened?

"Here is business enough for you."

Those were the words Gage spoke to the doctor as he walked in for treatment, and we can only imagine what must have been going through Dr. John Martyn Harlow's mind when Gage came strolling in after being involved in a horrific accident. The 25-year-old construction foreman was helping cut a new railway bed through Cavendish, Vermont, and was tasked with the dangerous process of using a tamping iron to pack explosives into a hole. For whatever reason, the explosives detonated early and sent the 4-foot, 13-pound iron pole through his left cheek, into his brain, and out his skull. The Smithsonian says he possibly didn't even lose consciousness.

According to Slate, he hopped onto a cart and was driven into town, where he sat on a porch chair and chatted to passers-by as he waited for the doctor. After a few days, he developed a brain infection that left him even closer to Death's door, but Death had apparently been impressed enough with what he'd already survived to give him a pass. He recovered, lost use of his left eye, and went home two months later.

Everyone who knew him before and after the accident agreed he had changed, and when he died in 1860 after suffering a series of seizures, he remained a part of historical and medical infamy.

He was a great case study for the early days of neurology

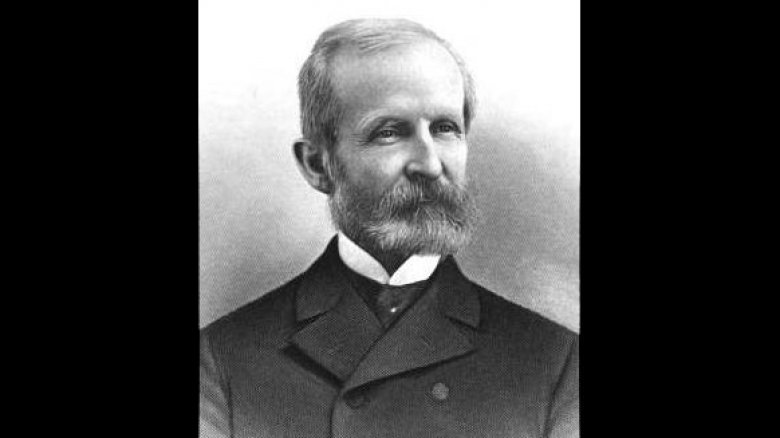

Gage is one of the earliest documented cases of traumatic brain injury, and according to ScienceBlogs, his accident couldn't have come at a better time — for neurology, at least. When Dr. Harlow (pictured) first documented Gage's story in the Boston Medical and Surgical Journal, no one believed it. It wasn't until Harvard professor Henry J. Bigelow wrote another piece on him — and how he was still a fully functional human post-accident — that people started to sit up and take notice. A follow-up report in 1868 focused on the "mental manifestations" of the accident. Even though he was functionally and physically fine, those who knew him before and after the accident said his personality was so different they said he was "no longer Gage." Harlow said he had become "fitful, irreverent, indulging at times in the grossest profanity ... manifesting but little deference for his fellows."

And there's the rub. At the time, the medical community was seriously divided on whether phrenology (assessing personality using bumps on the skull) or this new, up-and-coming thing called neurology was true. Neurologists were insisting we needed to look inside the brain to unlock the secrets of what made us human and unique, and Gage was the first documented cases that provided evidence for the neurologists. And they were right, so we should probably be thanking Gage for his contributions.

His case helped us pinpoint where things happen in the brain

There's still a ton we don't know about brain function, especially when it comes to things like memory and sleep. We can't exactly peek inside to see what's going on — at least, not without some serious legal ramifications — so we have to find other ways to get a look at brains.

Gage's accident has been bizarrely helpful in doing just that, and not just because Dr. Harlow could very literally peek inside his brain. We know what part of his brain sustained the most damage: the prefrontal cortex. And we know what happened to him afterward. His memory was intact. He was perfectly capable of working, traveling, and doing everything else a responsible grown-up should do. But although accounts vary on just how his personality changed, everyone agreed that it did change — and that's some pretty darn good proof our personality lives in our prefrontal cortex. Researchers from the Walton Centre for Neurology and Neurosurgery in Liverpool say Harlow's work with Gage set medical science on the right path, and it was followed by interest from David Ferrier about a decade later. Ferrier took Harlow's information and expanded on it, developing the idea that personality was largely governed by what was going on in the prefrontal cortex. Today, we know they were 100 percent on the right track.

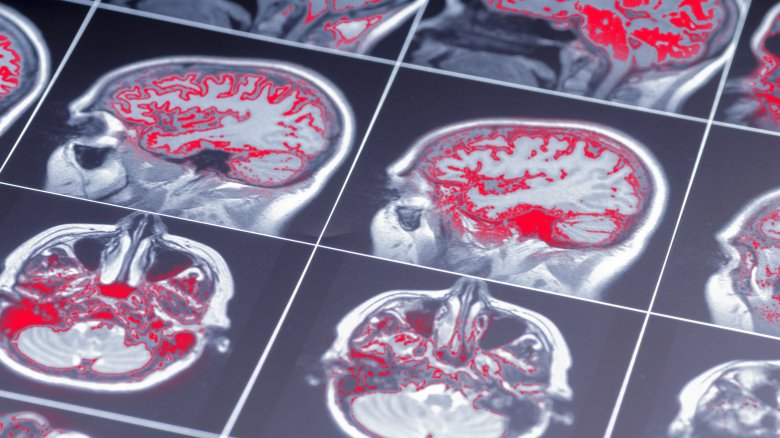

Modern technology is giving us some new insight

Technology has come a long way since Gage's accident, and it's a fortuitous — but slightly gross — bit of luck we still have his skull. According to neuroscience writer Mo Costandi, the official cause of Gage's 1860 death was complications from epileptic convulsions. No autopsy was performed after he died, but seven years later Gage's body was exhumed and his brother-in-law took both the skull and the tamping iron to Massachusetts. He gave them to Dr. Harlow, and now both artifacts are housed in Harvard's Warren Anatomical Museum.

While that means we don't have any direct information about Gage's brain, we do have two of the most important tools needed to recreate what happened to him. His skull was mapped and diagrammed as early as the 1940s, says NPR, and as technology has improved we've gotten increasingly better looks. In 2012, researchers from the Laboratory of Neuro Imaging used a combination of white matter imaging techniques, MRIs, and CT scans to map exactly what connections were severed when the tamping iron sliced through his skull. When they did, they found something pretty awesome — Gage's actual white matter likely sustained damage less severe than you might expect, similar to the damage done by a typical brain lesion. Pretty lucky for such a seemingly unlucky chap.

Do we really have the full story about his accident?

History is a funny thing. What we think happened and what actually happened often diverge in strange ways, and when the University of Akron took a look at some of the stories that have been compiled about Gage, they found lots of conflicting information, starting with the size of the tamping iron. While one paper reported it was 1.25 inches in circumference, it was actually 1.25 inches in diameter. That's a big difference, and when you're going by these reports to recreate the accident, that has drastic implications.

That's just the start of the misinformation. While some places say post-accident Gage was an absolutely depraved monster, other documentation shows he held down a number of jobs that came with quite a bit of responsibility, like driving a coach and caring for horses. At the same time we know he was working completely normal jobs, it's also written he exhibited himself in freak shows. It's written that he had no more social inhibitions, was a perpetual drunk, and even that he was described as psychopathic.

On the other hand, there's nothing in Dr. Harlow's writings that suggests anything of the sort. Quite contrary to the typical image of Gage, his mother testified he was eager to keep working after the accident and loved making up stories to tell his nieces and nephews. Psychopath, storyteller, or something in between? No one's entirely sure.

The misconceptions about him may have shaped our long-standing beliefs about the brain

We expect history to come with a little bit of embellishment, but the embellishment that was done with Gage's story may have changed our early thoughts on brain science. According to Slate, Gage's case is taught along with the idea that our humanity lives in our frontal lobes. Damage that, and you damage the very essence of a person. But what if Gage's personality change was largely falsified for the sake of making a better story? When historian and psychologist Malcolm Macmillan started on a journey to separate fact from fiction, he found a heck of a lot of fiction. He could only find a few hundred words documenting Gage's personality change from a first-hand source, but says he still "came to dominate thinking about the function of the frontal lobe."

The language used to describe Gage's personality changes can be interpreted in a number of ways. Dr. Harlow wrote of his "animal propensities," but what does that even mean? It could be anything from preferring his steak rare to trying to eat people. His cursing "at times" could have meant a tendency to say "gosh darn" or something worse. Given that we all actually have a baseline kind of behavior that varies dramatically by day and situation, it's entirely possible Gage's case was built on a lot of creative license. That's definitely not something you want to be basing an entire science on.

His case still forms a baseline for traumatic brain injuries

In 2012, Eduardo Leite's hard hat, skull, and brain were pierced with an iron bar removed after five hours of surgery. According to the medical personnel who treated him (via LiveScience), he was lucid, felt little pain during and after the incident, and had no long-lasting effects to his brain function, cognitive abilities, or even sensory functions.

Pretty incredible, for sure, but professors from the Neurological Institute of New York warned doctors not to get too excited about the apparent miraculous recovery. They looked to Gage's case as proof that a personality change could still happen, and that it might happen gradually or well after the physical wound seemed healed. They even cited Leite's nonchalant, rather unfussed attitude as proof there might be something unseen going on in his head. Most people would probably be pretty bothered if an iron bar was suddenly poking out from their forehead. The fact Leite wasn't? That's a sign something could be wrong, and thanks to Gage we know the changes could take some time to manifest.

He's proof of how difficult it is to measure some things

Gage was examined by Harvard Medical School personnel in 1849, when Dr. Henry Bigelow declared he had fully recovered from the accident. Slate says the tests that were likely performed would have measured a relatively limited number of things, like his eyesight, hearing, balance, and ability to speak coherently. Since he could do all those things, they figured his brain must be fine. We now know that's not true, but we still haven't figured out how to measure some of the changes Gage experienced.

In today's hospital settings, we can easily check up on eyesight, balance, and even intelligence and reasoning capabilities. But we can't judge if someone has suddenly developed a lack of empathy, different ambitions, or an inability to think about the consequences of their actions. Only people who know someone before and after a prefrontal injury can tell if these changes are present, and sometimes they're all but impossible to put into words. We can still look to Gage as proof that something happens, even if we can't find the words to describe what it is.

His success post-accident might help guide even modern treatment programs

In 1852, Gage picked up and headed off to South America, where he got a job driving a coach through the Chilean mountains. He did that for an impressive seven years, until declining health sent him back to California. Not content to just sit, he got a job doing farm work, and it's believed a particularly grueling day of plowing led to the seizures that ultimately killed him.

Historian Malcolm Macmillan says (via Slate) that his work in Chile may have contributed to his rehabilitation. Driving carriages takes some serious dexterity, as each horse is controlled by a different rein and a different finger. He also would have had to keep the stagecoach on a timetable, care for the horses on a strict schedule, and memorize the paths of the twisting mountain trails so he could follow them at night. He must have kept track of fares, and at the same time, he learned a bit of Spanish, too. That doesn't sound like the sort of thing an irrational, rash, unpredictable man could have handled.

Macmillan suspects Gage's success in Chile essentially served as therapy that helped him regain most of his mental functions and his personality — and that's helping shape therapies today. We know frontal lobe damage can impair a person's ability to complete tasks, and Gage's regimented Chilean schedule helped prove just how beneficial routine can be.

He's still used as an example of what we can overcome

There's a lot of terrible, gruesome stuff that's involved in talking about Phineas Gage, and unfortunately, we live in a world where terrible, gruesome stuff happens pretty often. According to NPR, he's still the poster child doctors point to when they want to show patients and their families what the human body and brain can overcome.

Malcolm Macmillan, who wrote An Odd Kind of Fame: Stories of Phineas Gage, has said that one of the things that struck him was that decades after the accident, he's still being used to tell patients what's possible. "Even in cases of massive brain damage and massive incapacity, rehabilitation is always possible," Macmillan said. If there's one good thing to come out of Gage's insane, life-changing accident, we think he'd be happy to be an inspiration to people going through the same horrible traumas. Horrible traumas are always going to be a thing, and people always need to be reminded what we're capable of.