The Untold Truth Of Ezra From The Bible

Ezra, son of Seraiah, is a major figure in the history of Judaism. A book of the Hebrew Bible is named after him, and based on his activities as the spiritual leader of the Jewish people following their return to the Holy Land following years of exile in Babylon. However, his story happens at the very end, chronologically speaking, of the Hebrew Bible and centuries before the start of the Christian New Testament, meaning that despite his hugely important contributions, Ezra might not get the same spotlight as earlier Jewish heroes like Moses or David, or later Christian figures like Peter and Paul. As a result, his story is less likely to, for example, get adapted into a cartoon for children starring vegetables.

So, who was Ezra? Why does he get a book of the Bible (or two, or three, or four) named after him? Why is it fair to say that the Bible as we know it might not exist at all without him? Read on and find out.

There is very little information about Ezra's early life

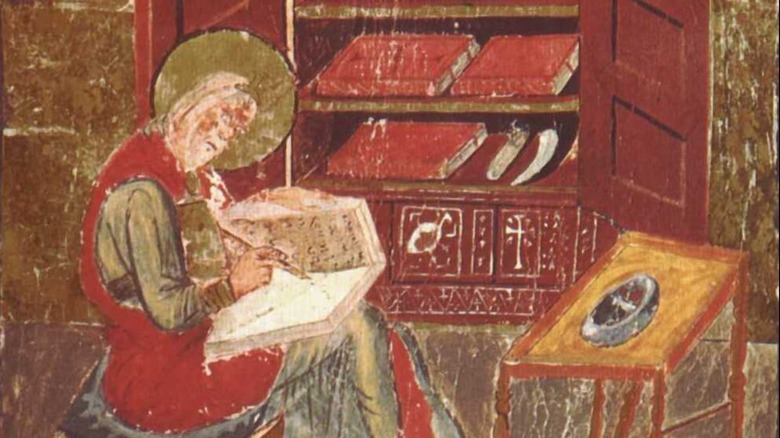

According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, Ezra the Scribe – also known as Ezra the Priest – was one of the most important figures of his time and had a broad and far-reaching impact on Judaism that lasts to this day, but despite that, biographical details on him are hard to come by. The primary source of information about the life of this influential scribe is his own memoirs, known today as the Book of Ezra, which is part of the Hebrew Bible. The name Ezra is likely an abbreviation of the Hebrew name Azaryahu, which means "God helps." In Greek and Latin translations of the Bible, the name Ezra is transliterated as Esdras.

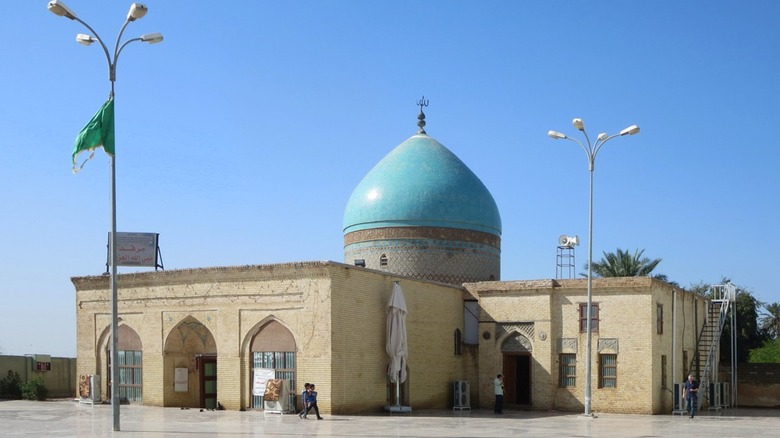

While Ezra was by profession a scribe, as Chabad explains, copying out the books of the Torah and the prophets, he was the son of Seraiah, the high priest, and thus of the priestly line, ultimately descended from Moses' brother Aaron, which is why he is also known as Ezra the Priest. He was born in Babylon (in modern-day Iraq) and lived there during the period known as the Babylonian Captivity, in which the nobles of Jerusalem were held in exile in Babylon following the destruction of the First Temple in Jerusalem by Babylonian forces. According to rabbinic tradition, Ezra was the student of Baruch ben Neriah, the scribe and friend of the prophet Jeremiah.

How many Books of Ezra are there?

The main source of information on Ezra comes from the biblical book that bears his name, but just which book is that? Figuring out what somebody means by the Book of Ezra might be trickier than you think. As My Jewish Learning explains, while the books of Ezra and Nehemiah are generally printed as two separate books in English Bibles, in the Hebrew tradition, Ezra and Nehemiah are considered to be two parts of the same book, which is called either Ezra-Nehemiah or just plain Ezra. The Encyclopedia Britannica adds that the two books were considered one and the same by Roman Catholics for some time, with some Bibles naming the two books as 1 and 2 Ezra, but Protestants have traditionally treated them as separate but related books.

The historical contents of Ezra-Nehemiah are chronologically the last in the Hebrew Bible and pick up from the end of 2 Chronicles, even repeating a few verses to really drive the connection home. This, combined with a similarity in style and thought, has led some scholars to conclude that the Books of Chronicles and Ezra-Nehemiah are the work of a single author. The Book of Ezra is primarily written in Hebrew, but some sections are written in Aramaic, a common language in the Middle East at the time that the Jewish people picked up during exile. The books of Ezra and Daniel (also set during the Exile) are the only books in the Hebrew Bible not fully in Hebrew.

No, really. How many Books of Ezra are there?

While it's already a little confusing trying to determine if everyone's on the same page when they're talking about the Book of Ezra, or Ezra-Nehemiah, or 1 and 2 Ezra, it gets even more complicated when you factor in that there are even more Books of Ezra in the mix. While these two books are not considered canon by Jews, their canonicity varies among different Christian churches. As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, one of these texts, also known as the Greek Ezra, is often called 1 Esdras, using the Greek form of the name Ezra. In fact, in the Septuagint (i.e., the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible), this book is placed before the Hebrew version of Ezra. As a result, in the Septuagint, the Hebrew Ezra-Nehemiah is named 2 Esdras. However, in the Vulgate (i.e., the Latin translation of the Old and New Testaments), the apocryphal 1 Esdras is placed after the canonical Ezra (1 Esdras) and Nehemiah (2 Esdras) and is thus called 3 Esdras.

The other notable text is the so-called Apocalypse of Esdras, which, depending on the numbering scheme being employed, might also be called 2 Esdras, 3 Esdras, 4 Esdras, or even 1 Esdras in the Ethiopic church. For the sake of clarity, from now on, this article will use the standard English naming convention of Ezra, Nehemiah, 1 Esdras, and 2 Esdras.

Ezra led the exiles back to Jerusalem

Before diving into the apocalyptic visions of the apocryphal Ezra, it's important to review the basics from the Hebrew Book of Ezra, which all Jews and Christians regard as canonical. As Chabad explains, the narrative of Ezra begins when the Persian king Cyrus the Great ascends to the throne and decrees that the people of Jerusalem may return to Judah now that the Persians have overthrown the Babylonian Empire. Even better, in a move of religious tolerance that Jews are not particularly used to, Cyrus ordered that the Jews should rebuild their Temple. Tens of thousands of Jews returned to Jerusalem and began work rebuilding the temple. This process was not without its troubles, as those who had come to live in the land of Israel while the Jews were exiled didn't love this huge crowd coming back, and not every successor to Cyrus was as sympathetic to the people of Judah.

Ezra did not go to Jerusalem with the first wave of returnees, choosing to remain in Babylon for motives that can only be speculated on. This additional time to study, however, gave him the opportunity to create detailed genealogies and ancestries for the people of Judah and become a prominent and respected figure among the remaining Babylonian Jews. After some delay, the reconstruction of the Temple was completed, and Ezra was tasked by the new Persian king, Artaxerxes, to lead the next wave of Jewish emigrants.

Ezra urged the Jews to stay separate from the world

Chabad continues by explaining that Ezra subsequently used his knowledge of the Jewish population to go from town to town in Babylon, informing Jewish families that they were free to return to Jerusalem, where the Temple was once again standing. Despite his efforts, most Babylonian Jews ignored his pleas and remained in Babylon. As a result, the second wave of returnees under Ezra's leadership was a relatively small crew of about 1,500 people, bringing with them as much gold and silver as they could carry to contribute to the Temple.

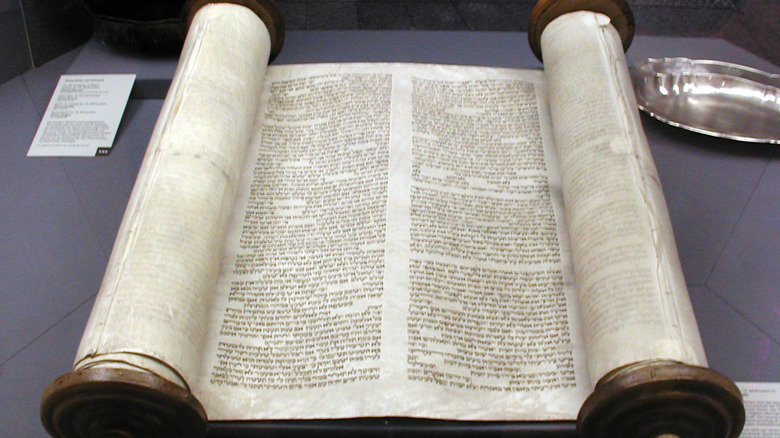

Upon Ezra's arrival in Jerusalem, he was shocked at how the people of Judah had been living in the years since their return under Cyrus's reign: they failed to keep the commandments, they ignored the celebration of holy days, and – worst of all in Ezra's eyes – they had intermarried with non-Jewish women from the surrounding area. When the people saw Ezra's shock and mourning at the spiritual state of his people, he was appointed leader in the effort to return his people to the proper worship of God. To this end, he commanded all Jewish men to leave their foreign wives and read the Torah aloud publicly to remind the Jewish people of its commandments. After some time, Nehemiah arrived from Babylon to serve as political and military leader for Jerusalem, rebuilding the city's walls and allowing Ezra to focus on the people's spiritual well-being.

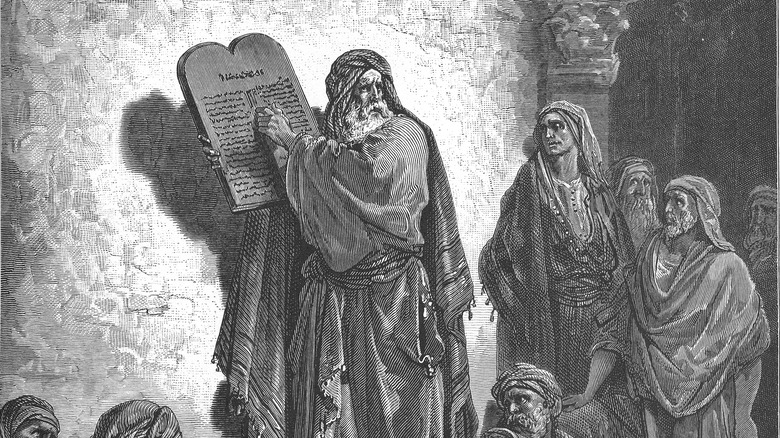

Ezra might have edited the Torah

While the Book of Ezra tells us that Ezra the Scribe reintroduced the Jewish people to the laws of the Torah after generations of exile, reminding them of God's law and the covenant of Israel to remain separate from other nations, some modern scholars go even further in their understanding of Ezra's relationship to the Torah. According to Haaretz, the traditional view of both Judaism and Christianity is that the Torah – the first five books of the Bible from Genesis to Deuteronomy – was written by Moses, most academics reject this, saying that differences in language, style, and theology, as well as repetitions and contradictions within the text, suggest that the five books are actually a compilation of several different texts patched together by an editor.

While the number of source documents is argued by scholars (four is probably the most commonly held belief), there is also believed to be an additional outside editorial voice who stitched the texts together and supplemented some material. This figure is called the Redactor, and some scholars believe that Ezra, the scribe who reintroduced the Torah to the people, might be that Redactor (Haaretz also suggests that Ezra might have been a significant contributor to one of the source documents as well). If this hypothesis is correct, then Ezra put together the first version of the Torah and is a monumentally influential figure in religious history.

The 10 major enactments of Ezra

According to the Talmud, the collection of rabbinic commentaries and clarifications on the Torah based on centuries of oral tradition, besides reintroducing the commandments of the Torah to the people of Jerusalem, he also instituted a number of laws to be followed by the Jewish people for their physical and moral betterment. As Chabad explains, the most important of these are known as the 10 Enactments of Ezra, and they dealt largely with Sabbath practices and ritual bodily purity.

For example, Ezra decreed that the Torah should be read publicly on the Sabbath, as well as Monday and Thursday mornings, and courts in Jewish towns should be in session on Mondays and Thursdays. Laundry should be done on Thursday so that your clothes will be clean in time for the Sabbath (which starts at sundown on Friday), and people should eat garlic – thought to have aphrodisiac effects – on Friday so that love might be made on the Sabbath. Women (yes, women specifically) have to wear underwear, and they should also bake bread on Friday mornings to give to poor people. Likewise, women should wash their hair prior to getting into a mikvah, a ritual bathing pool; tangentially, if a man has, you know, unexpected downstairs business while he's dreaming, he should clean up in a mikvah before studying Torah. These all make a kind of sense, but then there's also a rule that people should sell makeup door to door (seriously).

Men of the Great Assembly

Another major Jewish tradition surrounding Ezra is that he was the founder of a group known as the Men of the Great Assembly, which was a gathering of 120 Torah scholars, scribes, and prophets who issued rulings on religious matters at the very tail end of the era of prophets. As Chabad explains, this assembly was the greatest collection of Torah scholars in history and prefigured the later Sanhedrin, the supreme court of 71 scholars that played a key leadership role in Israel during the Second Temple period.

The members of the Great Assembly included a number of notable prophetic figures, several of which have books of the Bible named after them, including Daniel, Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi, as well as non-prophetic figures including Nehemiah, Mordecai (Esther's cousin from the Book of Esther), and the high priest known as Simon the Just. The Great Assembly realized that the era of the prophets was coming to an end and that the Jewish people were becoming increasingly scattered throughout the world, so they put together many enactments for the guidance of the Jewish people going forward, including systematizing the Oral Law that would eventually become the Talmud, codifying the canonical scriptures, and establishing rules for rabbis. The Great Assembly and the era of prophets ended with the death of Malachi, the last prophet, but thanks to the Assembly, the Jewish people now had the Torah and rabbis to guide them.

The Greek version of Ezra

The version of the story of Ezra from the Greek version of the Old Testament known as 1 Esdras is canonical in Eastern Orthodox churches but apocryphal in Catholic and Protestant churches. As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, its contents are largely excerpts taken from the books of 2 Chronicles, Ezra, and Nehemiah, with the figure of Ezra prioritized over that of Nehemiah. In the Septuagint, 1 Esdras is actually placed before the more widely canonical books of Ezra and Nehemiah, which are put together as 2 Esdras. This text was likely composed in the last century BCE or first century CE, which means most scholars attribute it little to no historical value.

But while the majority of the text is a reworking of the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, central to this book is an expanded narrative called the Dispute of the Courtiers, which serves as something of a fulcrum to the narrative. The story goes that the Persian king Darius held a contest between three of his courtiers in which they were to name the thing they thought was most powerful and then defend their answer. One said wine; the next said the king; the third said women, and the truth. This last answer wins, and the victor is revealed to be a Jewish man named Zerubbabel, who asks as a reward the return of the Jews from exile.

The Apocalypse of Ezra

While Eastern Orthodox churches consider 1 Esdras canonical, most churches see the Apocalypse of Ezra, also known as 2 Esdras, as apocryphal, aside from the Ethiopian Orthodox church, which has a version of it among their canon. According to the Jewish Encyclopedia, this book was composed as a way to deal with the question of suffering and must have come at a time of great distress for the author and their community. As with many books of this type, the main theme is the End Times, in which bad people will get what is coming to them, and the oppressed will finally get relief. References in the book to the Roman Empire, which destroyed the Second Temple in 70 CE, signifies that this one was probably put together near the end of the first century CE. (Comparing the suffering of the Jews under Babylon to that of Jews and Christians under the Romans is, of course, also the theme of the Christian Book of Revelation.)

In this book, Ezra the Scribe is given a series of seven visions from God through the archangel Uriel that attempt to answer Ezra's questions of how God can be just if his people are suffering. The visions include an eagle with three heads and lots of wings that is burned by a roaring lion; this eagle is Rome (or foreign oppressors in general), and the lion is the coming Messiah.

Other books attributed to Ezra

As a scholar and a scribe, it's no real surprise that a number of key writings have been attributed to Ezra. Besides the canonical books of Ezra and Nehemiah – which even secular scholars would agree a historical Ezra wrote at least portions of – and the books of 1 and 2 Esdras – which some churches believe are authentic documents of the scribe – there are a number of texts that some believe were written or at least edited by Ezra the Scribe. If, as Haaretz suggests, Ezra was not only the Redactor of the Torah but also one of the priests who worked on one of the major source documents, then he would have helped write huge portions of the first five books of the Bible, including essentially the entirety of the Book of Leviticus. As Chabad explains, the Talmud says that Ezra wrote the Books of Chronicles up to his own lifetime, but goes even a step further by saying that Ezra was actually the same person as the prophet Malachi and that he wrote the Book of Malachi, considered by Jews to be the last work of the prophetic era.

Medieval Christian tradition goes on to attribute other, much later works to Ezra, including the Greek Apocalypse of Ezra (not to be confused with the Jewish Apocalypse of Ezra, a.k.a. 2 Esdras) and the Latin Vision of Ezra, among others.

The many deaths of Ezra

The narrative of the life of Ezra within the canonical Bible ends with Ezra reading the Torah to the people in the public square, so there is no record in the canon of his death and burial. Fortunately, this is exactly the kind of detail that tradition and legend like to fill in. In fact, a number of competing traditions have risen up about the death and grave of Ezra the Scribe. As the Jewish Encyclopedia explains, one legend says that he died at the age of 120 in Babylon and was buried near where the Tigris River meets the Euphrates. Another legend says he died while working in the court of the Persian king Artaxerxes. The Jewish historian Josephus, however, says Ezra died in Jerusalem and was buried there.

According to Louis Ginzberg's Legends of the Jews, Ezra died in Persia on his way to see Artaxerxes after completing his earthly tasks. Columns of fire hovered over his grave at night, and a miracle is said to have happened there in which Ezra's ghost told a shepherd to have his grave moved to another location, with a plague tormenting the non-Jews of the town until the town's leader finally assented to the ghost's request and had Ezra's body moved to his desired spot.