The Untold Truth Of Salman Rushdie

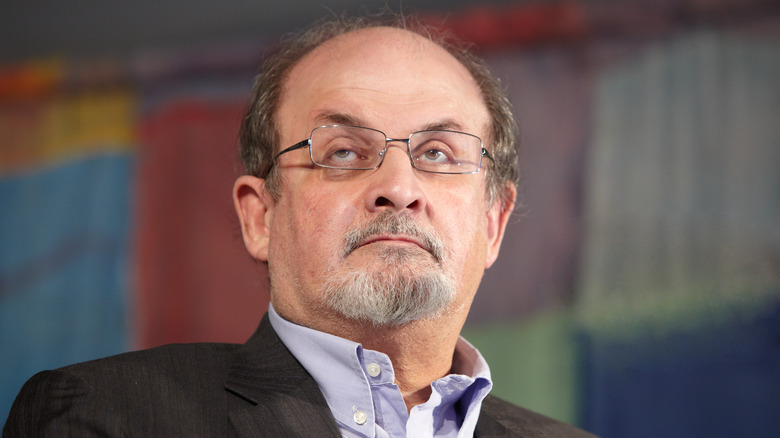

On August 12, 2022, author Salman Rushdie survived an assassination attempt in New York, when an armed assailant attacked him on stage. But this was not the first assassination attempt Rushdie has survived. As Time explains, there is a bounty of nearly $4 million for the death of Salman Rushdie, originally placed in 1989 by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the supreme leader of Iran. According to the Times of India, Iran has denied any involvement in the 2022 New York attack, but the attempts of the Iranian government to silence him have given Rushdie more cause than most to speak out about free speech.

Rushdie may be the best-known author to be attacked for his work, but he's not the only one. In 2016, Saudi author Aid al-Qarni was shot while giving a lecture (via Al Arabiya News), and Barnes & Noble lists five more writers who were likely killed because of their books — including Hitoshi Igarashi, who wrote the Japanese translation of Rushdie's work.

Ironically, while the ongoing threat to Rushdie's life began as an effort to silence him, Literary Hub notes that his books rapidly became bestsellers in the aftermath of the most recent attack. It is hardly worth it, though, since Rushdie has spent much of his life embroiled in controversy, including mass protests, decades of threats, and living under a false identity. This is the untold truth of Salman Rushdie.

Salman Rushdie started out as an advertising copywriter

Born in Bombay, India, in 1947, Salman Rushdie's career in writing had humble beginnings with no hint of the international notoriety he would eventually achieve. According to the National University of Singapore, Rushdie's big break as a writer came while he was working at an advertising agency, Ogilvy & Mather. A British company based in New York, Rushdie was a copywriter, creating slogans for marketing campaigns. Among his best known were lines like "that'll do nicely" used by American Express, as well as "irresistibubble" for Aero chocolate bars. Like many people who find themselves in such writing jobs, however, Rushdie had bigger plans. At the time, he'd already published his first novel, "Grimus," and was working on a second.

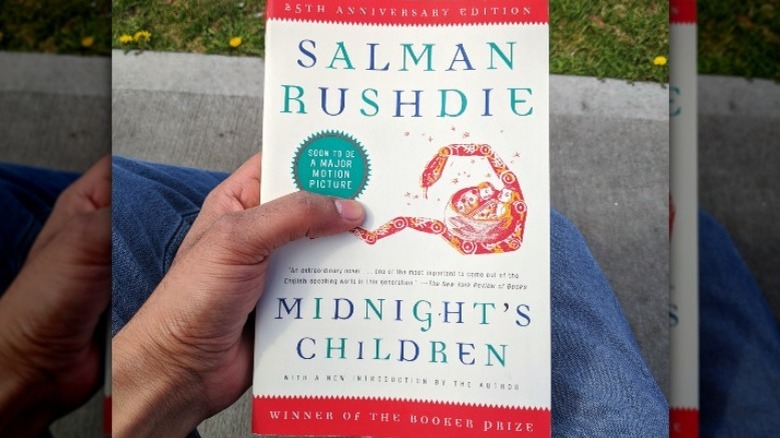

During his time with Ogilvy & Mather, Salman Rushdie wrote the novel "Midnight's Children," which was published in 1981. This novel would become his breakout hit, receiving acclaim for years to come. As the Guardian explains, "Midnight's Children" was written with a lot of ambition, leaning on the great Russian novels of the 19th century, like "Crime and Punishment," as well as traditional Indian epic tales like the Mahabharata. It also borrows stylistically from India's oral storytelling traditions, with digressions between the fantastic and the political. The New York Times notes how Rushdie became well known for the genre of magic realism, and "Midnight's Children" certainly laid the groundwork for the stories he would later pen.

He's a vocal feminist

Supporting marginalized people is something that Salman Rushdie has long been vocal about, and a lot of this is apparent in his writing. A paper in the journal Folklore uses his 1983 book, "Shame," as an example of this, set in a country described as "not quite Pakistan," and resonating with feminist themes. In the paper, literature researcher Justyna Deszcz explains how the story is a postmodern feminist reinterpretation of Beauty and the Beast. It also shows Rushdie's love of reenvisioning fairy tales, contorting them in a way to subvert commonly accepted Western narratives.

The novel isn't universally accepted as feminist, however. A 1992 article in The International Fiction Review notes that some critics have pointed out how it still reinforces patriarchal ideas, with women taking passive roles. The story is essentially a metaphor for colonial India, with the women representing the three influences of India, Pakistan, and England, not directly guiding the plot but nonetheless dominating the narrative.

While critics may disagree on interpretations of his writing, Rushdie considers himself to be unequivocally feminist. A 2015 article in The Cut asked him directly if he's a feminist, to which he gave the emphatic response, "Yes. What else is there to be? Everything else is being an a******." He cites being raised in a family full of strong female figures as having a significant influence on this.

He's a self-described hard-line atheist

Salman Rushdie's family background is rooted in Islam. As Biography explains, his grandfather was a devout Muslim, taking the Hajj and praying five times a day. However, Rushdie's family was also quite open and tolerant, allowing him to have frank discussions about faith and belief in God, or lack thereof. This left him with the freedom to choose his own path, and he would later refer to himself as a "lapsed Muslim." In a 1989 interview with Bomb Magazine, he explained that, while he was no longer religious and no longer believed in God, Muslim culture had significantly influenced his life and worldview.

Over time, while Rushdie would retain an appreciation for religion, he clearly saw it as something he didn't wish to participate in. In an interview with PBS in 2006, he describes himself as a "hard-line atheist," while also noting the irony that atheists tend to be obsessed with the idea of God. Unlike some other high-profile atheists, however, Rushdie never lost his appreciation for religion, explaining, "I do believe that religion at its best has given people profound solace in the travails of life." Rushdie continued to be vocally against the oppression of Muslim writers and intellectuals, as well as speaking up for women's rights.

Since 1989, Salman Rushdie has had a price on his head

The controversy for which Salman Rushdie would become best known revolved around his 1988 novel, "The Satanic Verses," which unleashed a storm of outrage for which he was completely unprepared. The Guardian talks about how it was banned in several countries and sparked global protests, including book burnings and even bookstores being firebombed. The issue eventually became so charged that Iran broke off diplomatic relations with the U.K. and, most famously, the Ayatollah of Iran put out a fatwā – a formal ruling in Islamic law – that Rushdie and everyone involved in his book's production should be executed. An Iranian religious foundation then announced that it would pay $1 million to anyone who killed Salman Rushdie, or $3 million if the killer was from Iran.

Shockingly, however, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini had never even read the book. An article in The New Yorker explains how the fatwā was issued as a political move, intended to exploit the outrage the book had caused. The controversy centered on one scene where the Prophet Mohammad appears in a dream sequence, which some Muslims considered blasphemous. This sentiment was not universal, however, even at the time. In Bomb Magazine, Rushdie's interviewer, a Muslim herself, noted that she didn't consider the book offensive.

Nonetheless, Rushdie would make a public apology in the New York Times, expressing his regret for the distress his book had caused to sincere followers of Islam. Unfortunately, though, the damage had already been done.

The first attempt on his life was in 1989

A few months after the bounty was put on Salman Rushdie's head, a bomb destroyed two floors of a London hotel. Created by a man named Mustafa Mahmoud Mazeh, a member of a terrorist group, The Times explains that it consisted of an explosive RDX charge hidden inside a book. Things did not go according to plan, and the bomb went off early, killing Mazeh. At the time, Rushdie had already gone into hiding with around-the-clock security for protection. His book had only been published the previous year, but this constant looming threat would follow Rushdie for a long time yet to come.

Decades later, Rushdie would still find himself under threat. In 2012, as the Times of India reports, he was forced to cancel an appearance at the Jaipur Literature Festival over threats to his life. The following year, The Wire reported that Rushdie's name was on an Al-Qaeda hit list. The threat, it seems, refused to ever fade away. Even in 2022, as CNBC reports, some people in Iran claim to be pleased that Rushdie was attacked – even though they weren't even born yet when "The Satanic Verses" was published. This sentiment, however, is now far from universal, with some expressing unease over the possibility that events following the attack could ultimately alienate Iran.

Salman Rushdie was once portrayed as a Bond-style villain

Following the Ayatollah's edict, Salman Rushdie became widely vilified, and perhaps the most bizarre propaganda against him came in the form of a Pakistani movie. "International Guerillas" (1990) has a plot revolving around a criminal mastermind and an international conspiracy to destroy Islam. Released as a direct reaction to Rushdie's book, Shock Cinema Magazine explains how the movie portrays Rushdie as an evil supervillain, describing the movie's blend of action, music, and comedy as "hallucinogenically awful." It even includes a divine intervention from God himself, involving lightning bolts and holy books which fire lasers.

Reportedly, "International Guerillas" was a success in Pakistan, but it was nearly banned from release in the U.K., according to Screen Online. The depiction of Salman Rushdie, likened to one of the over-the-top villains from James Bond movies, raised some well-justified worries that it could be seen as libelous. Eventually, it was Rushdie himself who stepped in and opposed the movie's censorship. He described the movie as "a distorted, incompetent piece of trash" but promised not to sue the creators over it. Ultimately, after its release in the U.K., the movie went largely unnoticed. Relegated to become little more than a bizarre relic of controversy, a copy of the movie is available to watch online, courtesy of the Internet Archive.

For years he went by the name Joseph Anton

The Ayatollah's fatwā was announced on February 14, 1989. In The New Yorker, Salman Rushdie explains how he jokingly referred to this as his "Unfunny Valentine," referencing the famous song. His sense of humor was a way to cope with the situation, which he explains felt violating. He'd go on to use every February 14 as a time to "reflect upon the countervailing value of love," spending many of these unfunny Valentines in hiding.

For a decade, Rushdie remained hidden, going by the alias of "Joseph Anton." It was clearly a difficult time in his life and, according to the Washington Post, he's described it in terms of humiliation and dishonor. The need for an alias was originally suggested by the British police, not only to hide his identity but to help the people protecting him, allowing them to get used to the name so they wouldn't let his real name slip in public. Inspired by great writers of days gone by, Rushdie created the name from Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekhov, taking to heart Conrad's words, "I must live until I die, mustn't I?"

The name would later become the title of Rushdie's memoir, recounting his time in hiding. As the Guardian explains, it was a poignant choice. The name had always caused him great discomfort, highlighting how unpleasant those years had been. In his own words, "It always felt very strange to be asked to give up my name."

He's outspoken about human rights in Kashmir

Kashmir is a contested region in South Asia, claimed by India and Pakistan. The conflict has resulted in serious human rights abuses (via Human Rights Watch). It's also a place close to Salman Rushdie's heart, being from a Kashmiri family himself. In 2019, Rushdie tweeted his denouncement of what was happening in Kashmir, saying, "even from seven thousand miles away it's clear that what's happening in Kashmir is an atrocity."

In an interview with Qantara, Rushdie talks regretfully about how military forces had destroyed the tolerant culture of Kashmir, and how his was one of many Muslim families which had been split in half by the ongoing conflict. Kasmir is the setting of Rushdie's book, "Shalimar The Clown," described in an interview with NPR as being "'Romeo and Juliet' in reverse." The story focuses on a couple from opposing Muslim and Hindu families. In it, the protagonist, Boonyi, gets married to Shalimar but finds herself in a claustrophobic situation that she needs to escape from. It's hard not to notice that the feeling of being trapped likely reflects Rushdie's personal experiences from his years in hiding.

The conflict in Kashmir is still ongoing as of 2022, and Rushdie is evidently on the side of India. He's previously expressed scathing criticism of Pakistan. In a talk show on The Forum Channel (via YouTube), he summarised his feelings bluntly, saying, "Pakistan sucks."

Salman Rushdie has complex political opinions

There's a fraught, decades-long history between the Western world and the Islamic world, and Salman Rushdie's opinions on the matter have been anything but straightforward. One point of contention in several European countries has revolved around women wearing the niqab, a veil that covers the face and leaves the eyes visible (not to be confused with the burqa). In 2006, as the San Diego Union-Tribune reports, the U.K. was debating whether the niqab should even be allowed.

Rushdie, at the time, was in favor of banning the niqab, viewing the garment as disempowering to women. Debates like this were likely influenced by the protracted Iraq War, which was ongoing at the time and, as Vice reports, fuelled strong islamophobic sentiment in Western countries. While it was clearly unintentional, Al Jazeera also points out that the Salman Rushdie affair played a significant role in the rise of Islamophobia in the U.S. and Europe.

The following year, according to the Guardian, Rushdie spoke in support of the U.S. intervention in Afghanistan and the attempt to break the Taliban's control of the Central Asian country. Simultaneously, however, he also condemned the U.S. invasion of Iraq, explaining that while there may have been good reason to remove Saddam Hussain from power, America's plans for a regime change were not internationally supported and therefore unjustifiable.

He was a supporter of the Occupy movement

In 2011, the Occupy movement was born out of frustration with the flagrant wealth inequality in America. Penn Today gives a retrospective on the movement, with its rallying cry of "We are the 99%" – a slogan which was nigh impossible to avoid hearing in the early 2010s. Protesters initially targeted Wall Street, but, with so many people affected by wealth inequality issues, there was plenty of anticapitalist sentiment to fuel the fire. The grassroots movement rapidly gained both popularity and influence, and, as the Guardian reported at the time, it soon spread around the world. Supporters came together from a variety of backgrounds, and one of those supporters was Salman Rushdie.

As Occupy continued to gain traction, it found plenty of backing from writers. According to the Guardian, Rushdie was among the first to sign the Occupy Writers petition, alongside other prominent authors like Margaret Atwood. The official Occupy Writers website is still online, as of 2022, listing Rushdie's name among the 3,277 writers who've publicly shown their approval of the movement.

Salman Rushdie has good reason to support free speech

The 2022 attack on Salman Rushdie has, as the Guardian notes, pushed the ongoing discourse on free speech back into the spotlight – although, as some have pointed out, the phrase is often misused as a right-wing euphemism. Rushdie's name was among those published by Harper's Magazine in 2020, co-signing a letter about the importance of free expression. This letter garnered mixed reactions. An article in The Atlantic notes that it's all too easy for some to view strong public criticism and "cancel culture" as an attack on free speech. However, after a government tried to have him killed, the issue of free speech is one with which Rushdie has far more experience than most.

During a visit to Brown University in 2021, Rushdie made the case for the preservation of free speech in a world where several countries are struggling to hold on to democracy. He explained his stance that prohibiting speech, even of the worst kind, could risk pushing it out of sight rather than preventing it from happening. He also noted that modern technology has made it much easier to spread false information, stressing the need to always debate the "limiting points of freedom."

Rather than assume his views to be correct, Rushdie is well aware of the importance of questioning his own convictions, believing that it's vital for every writer to argue with themself in a bid to constantly improve. With his turbulent history, Salman Rushdie's perspective certainly carries weight.