Chilling Details About Guantanamo Bay

Since it opened in 2002, Guantanamo Bay has spent the last two decades being a highly controversial symbol of America's War on Terror. Opened almost immediately after the 9/11 attacks, the prison is a sprawling, deeply militarized complex surrounded by high walls and barbed wire based on a remote, otherwise beautiful Cuban island, which the United States has rented from Cuba as a military base since 1898, as per The Infographics Show.

There are many terrifying facets to Guantanamo. For years few of the men and boys who entered had little chance of coming out, let alone securing fair treatment or a fair trial. In the eyes of many, they are considered to be the worst of the worst — men who have played a crucial role in the 9/11 attacks and therefore don't deserve the humane treatment guaranteed by international law.

Yet these claims have worn increasingly thin as the years have gone by. As the Council of Foreign Relations notes, many have voiced concerns about human rights violations and justice. Yet, despite endless accusations of cruelty, corruption and ineptitude, Guantanamo is still open. For many it remains a symbol of the terrifying consequences of American overreach and the dangers of unchecked state power.

For those who have been released, the scarring will never go away. Guantanamo remains their "Hotel California" — you can check out, but you can never leave.

Guantanamo pioneered detention without trial

Guantanamo Bay was made possible by the Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF), a law brought in only one week after the deadly 9/11 attacks in 2001. As the legal resource Lawfare points out, it effectively meant that the U.S. granted itself the right to use force when going after the citizens, organizations, or countries deemed to have played a role in the attacks. For the government under George W. Bush, this was interepreted as the right to detain terrorist suspects for an unlimited amount of time.

Needles to say, the fact that other countries had tried this, such as Britain's treatment of suspected Irish Republican terrorists in the notorious prison H-Blocks (via The Journal), and had firmly ended up on the wrong side of history, seemed of little value.

The result of the AUMF has meant that Guantanamo exists in a legal "black hole" where international law doesn't apply and where habeas corpus petitions (a legal mechanism that allows prisoners to report their unlawful detention to a court, as per Cornell Law School) filed by inmates are left in the hands of courts in Washington, D.C., to decide on. A body of "common law" (or unwritten laws based on legal precedents, as per Investopedia) has sprung up around the inmates due to all the legal battles, but it has provided little clarification around detainee rights.

Inmates like Ramzi bin al-Shibh potentially face the death penalty, even though, as detailed by the New Yorker, his legal team was infiltrated by members of the CIA.

Scores of prisoners have been kidnapped

Numerous inmates were sent to Guantanamo without trial, with the complicity of local forces and often with families having no idea where their loved ones were. Many did not find out for years that their families were in Guantanamo.

The family of inmate Mohamedou Ould Slahi was led to believe that he was in a prison in his home country of Mauritania, according to Slahi's "Guantanamo Diary," edited by Larry Siems. His family provided clothes and money for his food, but it was all trousered by the prison guards. Slahi had been grabbed by U.S. forces, taken to Jordan, then to Afghanistan, and then to Guantanamo. It was almost a year later that one of his brothers saw an article about him in the German magazine Der Spiegel and realized that he had been kidnapped. Local forces nor the U.S. had not once taken the trouble to inform them of this. Understandably, they were rather incensed.

Another inmate, Mansoor Adayfi, was kidnapped by Afghan warlords keen to take American money and sold to the CIA, who then had him sent to Guantanamo for 14 years, according to an interview with Democracy Now! He was kept there without charge or trial and subject to brutal and inhuman treatment. He described Guantanamo as being less about safety and more about being "designed to strip us of who we are. Even our names were taken."

People with no links to terrorism have been held there

Inmates like Mohamedou Ould Slahi were proven as no threat to the U.S., brought in on the accusation that he had joined Al Qaeda during Afghanistan's war against Russia — a conflict that America supported, as per The Indian Express. He was released in 2016 after 14 years in Guantanamo, never having been charged with a single crime.

Prisoners like Abu Zubaydah are still being held in Guantanamo for their involvement in the early-2000's conflict in Afghanistan, despite the war being officially over — a situation that normally mandates the release of prisoners of war. According to the Guardian, Zubaydah was never accused of having links to 9/11 or Al-Qaida, the group responsible for the attack on the twin towers.

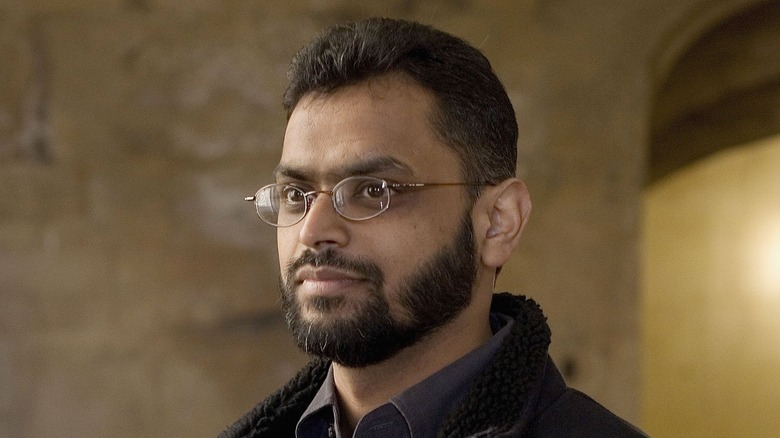

Other high-profile innocents who have done stints in Guantanamo include Shaker Aamer, a British citizen who, according to Amnesty International, was detained in Guantanamo without charge or trial and held there for 13 years. Moazzam Begg, another British citizen, was kidnapped and held for three years in Guantanamo, being told explicitly upon his arrival that he had didn't have any rights (via Al Jazeera).

All were subjected to torture and abused while in Guantanamo.

Daily life is hell

Some reports of life in Guantanamo have stated that the prisoners have access to video games, DVDs, a select few TV channels (according to the Infographics Show) and other creature comforts — and this was certainly the case with Mohamedou Slahi after a long period, according to the New Yorker.

Yet the Infographics Show describes how many of the men have experienced confinement in wire enclosures with barely enough room for them to stand. Cells often lack basic amenities, like toilets or proper beds, and are devoid of light. Guards are encouraged to slam doors to prevent people from sleeping (via The Guardian), and many are handcuffed for hours on end. Beatings are common and random, and prisoners who need to move around are strapped onto a trolly with metal clamps. Those who walk wear shackles, which causes swelling in the ankles.

Prisoners on hunger strike are given water containing basic nutrients, but if they refuse then they get force-fed. Many detainees have been left to sleep on concrete afterwards as punishment for those protests.

Physical isolation and an enforced lack of contact from loved ones has been the lived reality of many prisoners, being allowed no visits with anyone other than their lawyers. The closest Slahi got was a letter from his mother forged by the U.S. State Department, saying she feared being locked up for not cooperating with her interrogators — a tactic designed to manipulate him, according to his "Guantanamo Diary."

Torture and physical abuse are common

Accusations of torture and intimidation within Guantanamo have been rife. The U.S. government has tried to obfuscate their practices by describing them as "enhanced interrogation" techniques, as per The Guardian. The Infographics Show describes how inmates have been waterboarded (a process best described as "simulated drowning"), beaten, subject to stress positions such as standing or crouching for indefinite periods until the blood rushes away from their limbs (threatening eventual amputation), sleep deprivation, and being held in a box like a coffin.

This comes alongside other practices designed to humiliate the inmates, such as forced nudity, sexual assault, and being dragged through their own urine. Doctors monitor the vital signs of prisoners to make sure they aren't killed in the process. Medical staff have been told to put aside their usual ethical concerns (including the Hippocratic Oath) when assisting the torturers, as per Harper's Magazine.

Other forms of "interrogation" have included being subject to deafeningly loud levels of music (bizarrely, the "Sesame Street" theme was in the mix), bright lights, and extreme temperatures. Prisoners like Mohamedou Slahi were put in cells where music blared out almost constantly, giving him little respite, as highlighted by the New Yorker. The methods used in Guantanamo have come to be regarded as some of the most brutal ever carried out in modern times.

Meanwhile, some of the bands whose music was used as a present-day equivalent of thumb screws started a campaign in protest against it. They included Metallica, Rage Against the Machine, and Britney Spears, reports The Guardian.

Censorship is rife

It wasn't until 2006, four years after the prison opened, that the U.S. government published the names of 558 people being held in Guantanamo. According to the Guardian it was only three-quarters of the total.

Furthermore the Pentagon has redacted attempts to tell the world about conditions in the prison, including Mohamedou Slahi's book "Guantanamo Diary," without the permission of inmates or their lawyers. A 2004 report from the CIA, titled "Counterterrorism and Detention Interrogation Activities, September 2001-October 2003," made it clear that the agency wishes to keep people from giving details about the circumstances of their incarceration, as per Slahi's diary. The full version of Slahi's book was only released in 2015, a year before he was freed, as per The Indian Express.

The Infographics Show highlights how journalists and photographers who try to visit the camp face serious restrictions on the photos they can take and release, and many are rarely allowed inside at all. To even arrive requires permission from the military base's commander, which isn't easy to obtain.

Cover-ups are common

Groups like Wikileaks have released official documents detailing the treatment of detainees in Guantanamo, including where the men came from and the circumstances in which they arrived. The Wikileaks report highlighted salient details within a tranche of secret documents, including how hundreds of inmates were either mere underlings for groups like the Taliban in Afghanistan, had no links to international terrorism, or were even just plain innocent.

Wikileaks further makes the point that these people were often captured because the Bush Administration ordered there to be no screening of those snatched by the military. Many were brought in by well-paid bounty hunters, employed by America's allies in Pakistan and Afghanistan.

The attorneys for the prisoners were not immediately granted the right to see these files. When they were, they were forbidden from downloading, printing or saving them, according to journalist and Guantanamo expert Andy Worthington.

Other attempts to get the truth from the U.S. government about some individual cases have been impeded by tech issues during interviews. When Mohamedou Slahi tried to recount his experiences inside Guantanamo to the prison review board, the transcript states that there was an issue with the recording equipment. The missing section of the transcript was apparently the point where Slahi presented details on how he was tortured and by whom. The recap placed in the document mentioned the abuse, but did not give details, as recounted by Larry Siems in "Guantanamo Diary."

It's based on flawed intelligence

Many of the inmates held in Guantanamo had no link with the 9/11 attacks, and members of the intelligence community confirmed that many of them posed no threat to the United States. Even in 2002, the Los Angeles Times (via "Gauntanamo Diary") reported that the nearly 600 or so detainees held in Guantanamo were not linked to Al Qaeda. The article quoted government sources that said that the inmates were in no way "high enough in the command and control structure to help counter-terrorism experts unravel Al Qaeda's tight-knit cell and security system." These thoughts in turn were echoed in an audit conducted by the CIA.

Wikileaks highlighted how so many of the prisoners were insignificant to the War on Terror that the authorities didn't even try to create a case against them. Their detention was often based on unreliable reports from fellow prisoners.

The New Yorker draws attention to how the prison staff member guarding Mohamedou Slahi, Steve Wood, slowly started to suspect that the case against him was flimsy and that he was being kept there to cover up the American government's embarrassment at having made a mistake. Slahi also believed he knew too much about the camp's secret torture regime to be released.

It breaks international law

Under both the Obama and Bush administrations, the U.S. has insisted on arresting and detaining those it deems a threat under the laws of war. These edicts can trump human rights law, particularly when those detained pose a major security risk during conflicts between states.

However, international human rights law mandates that beyond a battlefield situation, anyone detained must be treated according to the terms of the Geneva Convention and in line with domestic or international laws, according to Human Rights Watch. The latter, which includes the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ratified by the U.S. in 1992), forbids indefinite detention without trial.

Furthermore Human Rights Watch states that when the Afghan government under Hamid Karzai was established in 2002, prisoners should have been repatriated, or if guilty charged with war crimes.

The organization criticized how instead of imposing criminal charges and fair trials, the U.S. gave the authorities the power to lock people up for as long as they liked without the need to prove criminal culpability or showcase evidence in court. However, there is no one to enforce these rules.

Guards who object are ignored or silenced

It would be fair to say that life for staff at Guantanamo is a whole other story. The Infographics Show highlights the range of distractions available during their downtime, including bars and water sports, and branches of McDonald's and Starbucks.

Yet according to Mohamedou Slahi's "Guantanamo Diary," edited by Larry Siems, security staff working at Guantanamo have also spoken openly about their doubts over the inmates being treated as the enemy rather than prisoners of war, which would give them protection under the Geneva Convention. In August 2002 journalists visiting Guantanamo were told by the commander of detention operations that staff had concerns. The response of the Pentagon was to replace him and increase their intelligence operations. According to the New Yorker, this was because collecting flawed intelligence was considered more important than prosecuting acts of terrorism.

The magazine further describes how James Yee, the Muslim chaplain for the camp, requested that guards stop abusing copies of the Quran after 23 prisoners tried to hang themselves using their bedclothes. His comments were ignored. Yee later realised that Muslim American staff at the camp were being spied on, himself included. He was eventually arrested, interrogated, and imprisoned in South Carolina. He was accused of posing an insider threat to the military. All charges were later dropped.

When Steve Wood started to have mixed feelings about Slahi, he felt didn't want to ask to many questions in case he seemed unpatriotic. He secretly forged a strong bond with Slahi, converted to Islam, and spoke out against what he saw in Guantanamo.

Attempts to close it have been blocked by Congress

President Joe Biden has declared the war in Afghanistan to be over, while the people in Al Qaeda responsible for the 9/11 attacks are all captured or dead. Yet attempts to close Guantanamo have repeatedly hit a brick wall, with members of America's security apparatus insisting the inmates are still of interest to the intelligence agencies.

As of January 2022 there are 39 prisoners in Guantanamo (via Politico). Many of them have nowhere to go. Congress has deemed it Illegal for them to be brought to the U.S, notes the Infographics Show.

As a government lawyer, Lee Wolosky describes in Politico how hard it has been to convince other countries to take in the detainees, due to the stigma of Guantanamo. The hotch-potch legal system governing it is hard to untangle, made harder by an extremely polarized political environment in the U.S. Some countries expressed an interest in taking detainees but demanded outsized rewards in return (such as lucrative military contracts). The result was a break-down of talks. On top of this, the Trump Administration quashed any hopes of closing the prison during his presidency as a way to reverse President Barack Obama's legacy. Its closure continues to be a game of politics.

There's talk of conditions having improved, as per the Infographics Show, compared even with prisons in many U.S. states, to compensate for past scandals. Yet more detainees have died at Guantanamo than have been convicted of a crime, reports the New Yorker. The older inmates are likely to die there. It is a sobering reminder that the camp will always be synonymous with social injustice.