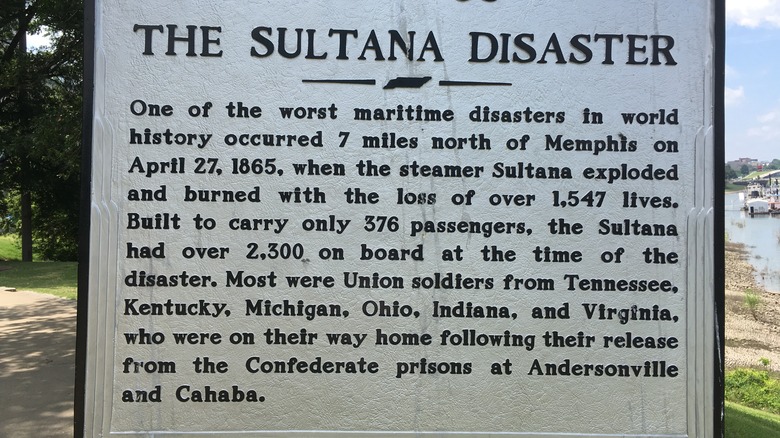

The Worst Maritime Disaster In United States History

Although the Civil War was the deadliest war in United States history, it's only tangentially responsible for the worst maritime disaster in U.S. history, which happened to occur less than a month after the end of the war.

After the Civil War ended, former POW soldiers from both the Union and Confederate sides were sent back to their respective sides. And while some made it back to their families in relatively one piece, some soldiers found themselves on the unluckiest transport of their lives.

Despite having survived a war and being a POW, hundreds of soldiers ended up taking their last breath on a steamboat on the Mississippi River, thinking that they were finally on their way home. Instead, their worlds would be rocked by an explosion that many have argued could've been avoided. And if that wasn't bad enough, few would ever know of this accident, largely due to it being overshadowed in the newspapers. This is the story of the worst maritime disaster in United States history.

What was the Sultana?

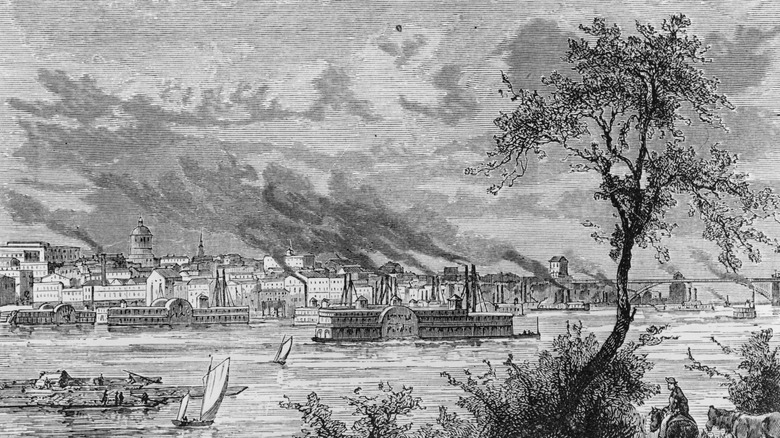

The Sultana was a privately owned Mississippi River steamboat that was launched on January 2, 1863. According to "Destruction of the Steamboat Sultana" by Gene Eric Salecker, it was actually the fifth steamboat to be given the name Sultana and two out of its four predecessors also saw their demise through flames. And after the fourth Sultana burned up in 1857, there wouldn't be another Sultana until number five was built in a boatyard near Cincinnati in the winter of 1862.

Initially, the Sultana was owned and captained by Preston Lodwick. He owned it for a little over a year, during which time the United States government requisitioned the boat to transport troops and cargo during the American Civil War. Salecker notes in "Disaster on the Mississippi." Steamboat captains and owners often feared the requisition of their boats because they would often be loaded beyond their legal capacity and have their complaints ignored. "Masters of steamboats soon found that it was useless to protest any requisition or overcrowding; the military always had its way."

We're History writes that after steamboats started being used in the 19th century, boiler explosions were, unfortunately, a fairly common occurrence. Between 1816 and 1848, it's estimated that there were at least 233 boiler explosions on steamboats. It wouldn't be until the Steamboat Act of 1852 that standards were set for boiler construction and operation. However, "steamboats still caught fire and blew up with some frequency."

News of Lincoln's assassination

By 1864, the Sultana was bought by Captain James Cass Mason but by early 1865, financial troubles led him to sell several parts of his investment. According to "Disaster on the Mississippi," by April 1865, "Mason had regressed from a three-eighths majority owner in the Sultana to a one-sixteenth minority shareholder."

On April 14, 1865, the Sultana stopped at the Cairo wharf in Illinois on its way to New Orleans. And when President Abraham Lincoln was assassination the following day, the Sultana was the first boat to leave Cairo carrying extra copies of the Cairo Democrat newspapers to spread the news of the assassination.

Sailing with the flag at half-staff and black fabric draped over the railings, Salecker writes that the Sultana stopped at every city, town, private landing, and military fort on its way downriver to report Lincoln's assassination. Because telegram wires in the South were largely destroyed, the Sultana was one of the ways that news of Lincoln's assassination was able to travel across the South. "Captain Mason intended to go down in history as the first boat to spread the news of Lincoln's death." "Destruction of the Steamboat Sultana" writes that news of the assassination was shouted along the way, and when the steamboat got to Memphis, copies of the Cairo newspaper were passed out.

Picking up former POWs

When Mason's share of interest in the Sultana dropped to just one-sixteenth, he and the other owners joined with other independently owned steamboats and formed the Merchants and People's Steamboat Line. And "Disaster on the Mississippi" writes that the association took a contract with the United States government to transport freight and troops. And the government paid handsomely for doing so.

As a result, when the Sultana reached Vicksburg, Mississippi and Captain Mason was approached by Captain Reuben Hatch to transport Union soldiers that were former POWs, the money seemed too good to pass up. "Destruction of the Steamboat Sultana" writes that the terms of the contract stipulated that the government would pay $9 per officer and $3.25 per enlisted person that was transported north.

Hatch approached Mason with a proposition. If he could guarantee 1,000 former POWs for Mason to transport, would Mason give him a percentage of the money he earned? There was a lot of money to be made with 1,000 former POWs, but Mason was unlikely to access 1,000 former POWs to transport without Hatch's help, Salecker writes. By carrying the former POWs, Mason stood to make about $2,500, worth over $40,000 today, per The Sultana Association. Considering his financial predicament, Mason agreed and continued downriver towards New Orleans, with the intention of stopping by Vicksburg on the way back to pick up the former POWs.

Repairing the boiler

After making it to New Orleans, the Sultana set off on its trip back up the river on April 21, 1865, carrying over 120 people, and over 1,000 pounds of cargo. According to "Destruction of the Steamboat Sultana," there was also a pet alligator "that was kept in a sturdy wooden box inside one of the paddle wheel housings."

Roughly 100 miles outside of Vicksburg, the Sultana started unexpectedly slowing down, and it was discovered that there was a leak in one of the Sultana's four boilers. The Sultana made it into the Vicksburg wharf on the evening of April 23, and the following day, former POWs started arriving, writes The Sultana Association. But according to Salecker, Mason was told that he was going to be paid only $8 per officer and $2.75 per enlisted person. As a result, he'd have to transport more former POWs if he was going to get the payday he had anticipated.

Meanwhile, the boiler needed to be repaired, but Chief Engineer Nathan Wintringer was told by R.G. Taylor, a boilermaker, that the repair would take a couple of days at least. Knowing that the Sultana couldn't spend two days waiting for repairs, Wintringer convinced Taylor to do whatever work he could on the defective boiler before the Sultana set off again. "Perhaps against his better judgment, Taylor relented," and he performed some minimal repairs on the boiler.

Loading the Sultana

While the boiler was being repaired, Captain Mason went off to find more former POWs to transport in order to plump up his final payment. But according to "Disaster on the Mississippi," Mason soon realized that this was going to be even harder than he originally thought.

Because the lists of former POWs had yet to be finalized, Mason was told that there would only be about 500 former POWs for him to transport, at most 700. But after Mason threatened to complain that his contract with the government was being broken, Union Army Captain George Williams proposed an arrangement. "Perhaps the names of the prisoners could be checked off on the books supplied by the Confederate commissioners and the rolls completed afterward from the books." This way, the former POWs could be sent off on the Sultana while the lists were still being finalized.

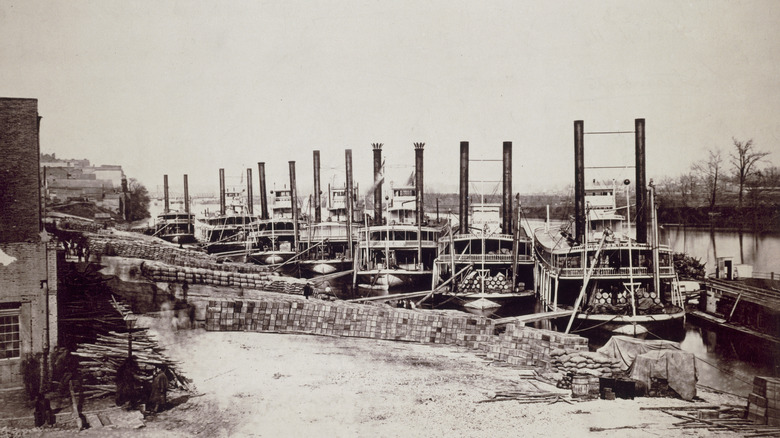

Captain Frederick Speed agreed to this arrangement and estimated that there were roughly 1,300 former POWs that they could arrange for transport on the Sultana. But according to The Sultana Association, when the Sultana set off from the Vicksburg wharf on the evening of April 24, 1865, there were up to 2,500 people on board, over 1,900 of whom were former POW Union soldiers. This despite the fact that the Sultana's legal carrying capacity was 376, reports NPR.

Exploding outside of Memphis

As the Sultana sailed upriver, even Captain Mason couldn't ignore how overcrowded the boat was. According to The Sultana Association, Captain Mason had to tell the people on the ship not to rush from one side to the other to wave at passing steamboats because the Sultana might capsize from the sudden shifts in weight. Plus, all the back and forth was causing the water in the boilers to move back and forth, causing some of the boilers to heat up and turn the water into instant steam once it moved back into the boiler.

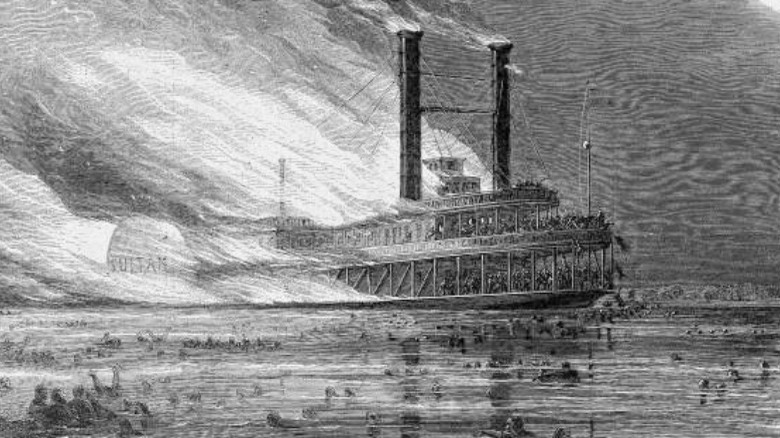

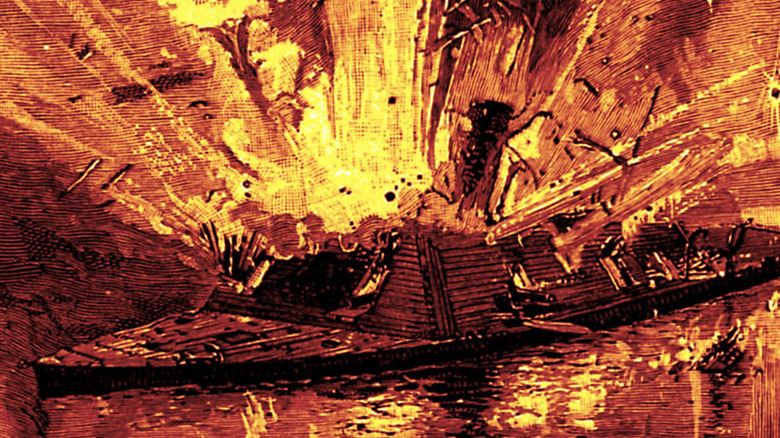

NPR writes that around two in the morning on April 27, 1865, the Sultana was only a few miles north of Memphis when three of its boilers exploded "and the entire center of the boat erupted like a volcano." Coeur d'Alene Press reports that the sound could even be heard all the way back in Memphis, while the "sudden stabbing pillar of fire that lit up the black, swirling river and was visible for miles."

The explosion ripped up through the Sultana, but, because it didn't come from the furnace fireboxes, it took a few moments for the Sultana to burst into flames. In the meantime, the smokestacks toppled down, smashing the boat and crushing dozens of soldiers. As the Sultana burst into flames, those who survived the explosion and managed to outrun the flames abandoned the boat.

Stuck in the Mississippi

Hundreds of people continued to jump into the water in an attempt to avoid the growing flames on the Sultana. But as more and more people leaped into the water, there was less and less floating debris for them to grab onto. The Sultana Association writes that "men and women grabbed onto each other as they fought a life-or-death battle to keep their heads above the freezing, swirling waters."

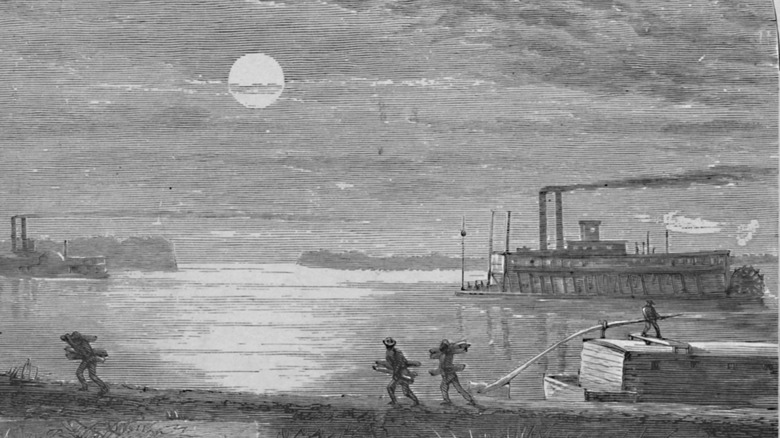

Before long, another steamboat, the Bostona, came across the site of the catastrophe. Throwing overboard any floating items to help the survivors stay afloat, the Bostona was able to take aboard only 150 people. According to Coeur d'Alene Press, one person managed to stay afloat by holding onto a dead mule.

Within a few hours, survivors of the Sultana explosion were even floating by the docked steamboats at the Memphis wharf. But unfortunately, the Memphis steamboats had to "wait for enough pressure to build in their cold boilers" before they could rescue anyone. Upriver, near the burning wreck of the Sultana, many floated to flooded rooftops and waited there for rescue.

Rescuing the survivors

While Memphis steamboats slowly got ready, smaller boats were sent out to rescue people floating by the Memphis waterfront. But according to The Sultana Association, some of the survivors had to wait until at least seven in the morning to be rescued. And at least 25 soldiers who were stuck on the bow of the still-burning Sultana managed to be rescued just moments before the Sultana finally sank.

And Smithsonian Magazine writes that some of the survivors ended up on the Arkansas side of the Mississippi River, which was controlled by the Confederates at the time, and they were saved by local residents. In fact, many of the Confederate soldiers who saved the Union soldiers from the Mississippi River may have been shooting at that very same soldier just a few weeks earlier. And now, instead of shooting at them, they were giving them refuge in their homes.

Civil War Prisons writes that roughly 800 survivors were found and taken to hospitals in Memphis, but up to 300 ended up dying from burns and exposure.

Worse than the Titanic

The Sultana disaster was the worst maritime disaster in the history of the United States. Killing between 1,200 and 1,800 people, the Sultana disaster is thought to have been even worse than the sinking of the Titanic, which only killed 1,512 people in comparison.

Because former POW Union soldiers from Kentucky and Tennessee had been crowded next to the boilers, they were some of the first casualties of the explosion, according to NPR. Hundreds died from the shrapnel, the steam, and the boiling water, while hundreds more died afterwards from the fire, drowning, and exposure.

Unfortunately, despite the large death toll, few registered the Sultana disaster. The Smithsonian Magazine writes that due to the unfathomable Civil War, "the public's news fatigue was at a high, and the death of fewer than 2,000 people — stacked up against the roughly 620,000 soldiers" just didn't register on a national scale. In many Northern newspapers, the Sultana disaster was just a minor story on the back pages.

What caused the explosion?

Despite the lack of national attention towards the disaster, the United States government was still interested in investigating the cause of the Sultana explosion. According to The Sultana Association, the government initially considered that the explosion was the result of sabotage, but this idea was quickly disproven.

Ultimately, it was determined that the Sultana explosion was due to "faulty boilers, too much steam pressure, and not enough water in the boilers." Because the one surviving boiler was found to be scorched from the inside, the steamboat was likely running with too little water. According to "Destruction of the Steamboat Sultana," it also turned out that Henry J. Lyda, the steward of the Sultana, resigned his position just 10 hours before the Sultana was about to leave for Cairo from St. Louis, Missouri, stating that "the Sultana's boilers were not fit for duty" and that he wasn't willing to spend another trip on the boat.

As a result, the Sultana was clearly a ticking time bomb waiting to go off, considering how overcrowded it was at the time of the explosion.

No accountability for the disaster

On January 9, 1866, Captain Speed, who'd been responsible for sending the former POWs to the Sultana, was put on trial for overloading the Sultana with people. And exactly six months later, in June, Speed was found guilty of three charges of criminal neglect and carelessness by overloading the Sultana. But according to The Sultana Association, although Speed was initially found guilty, his conviction was soon overturned by the judge advocate general of the army, Brigadier General Joseph Holt.

On June 21, 1866, Judge Holt ruled that "Speed took no such part in the transportation of the prisoners in question as should render him amenable to punishment," per "Disaster on the Mississippi." Holt maintained that whatever part Speed played was as a subordinate and that he shouldn't be held responsible for the deaths of the Sultana disaster.

Although Holt ruled that Captain Hatch was to be held responsible for the overcrowding, Hatch ignored three different subpoenas to come to Vicksburg. And even when a United States Marshal was sent to arrest him, Hatch was nowhere to be found. But even if Hatch could be found, he couldn't be compelled to testify before a military tribunal because he wasn't in the Military Service and wasn't within the jurisdiction of the Court. As a result, no one was ever held responsible for the Sultana disaster.

What happened to the Sultana?

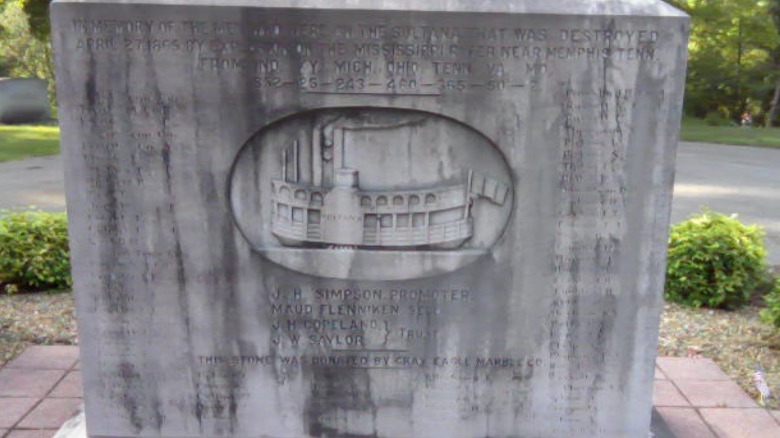

Few remembered or even knew of what happened to the Sultana. In 1892, one of the survivors, Chester D. Berry, lamented that "The idea that the most appalling marine disaster that ever occurred in the history of the world should pass by unnoticed is strange, but still such is the fact," per "Hidden History of Cincinnati" by Jeff Suess.

The Sultana remained largely forgotten for over a century until its wreckage was believed to be found during an archeological expedition in 1982. According to The American Stamp Dealer & Collector, because the Mississippi River has changed course several times since the Civil War, the wreckage of the Sultana was found under a soybean field on the Arkansas side of the River, roughly four miles away from Memphis. Sultana: Greatest Maritime Tragedy in United States History writes that attorney Jerry Potter was the first one to propose the archeological site for excavation, where several samples of charred wood and glass were found. However, there isn't much definitive evidence to suggest that the wreck that was found is definitely the Sultana.

In 2015, on the 150th anniversary of the sinking, the city of Marion, Arkansas, decided to reignite the memory of the Sultana by creating a temporary museum and hosting events to bring attention to the disaster. According to NPR, the temporary museum contained personal items from soldiers, pictures, pieces of the Sultana, and a 14-foot replica of the steamboat.