The Untold Truth Of Charles Addams, Creator Of The Addams Family

"They're creepy and they're kooky, mysterious and spooky, they're all together ooky — The Addams Family!"

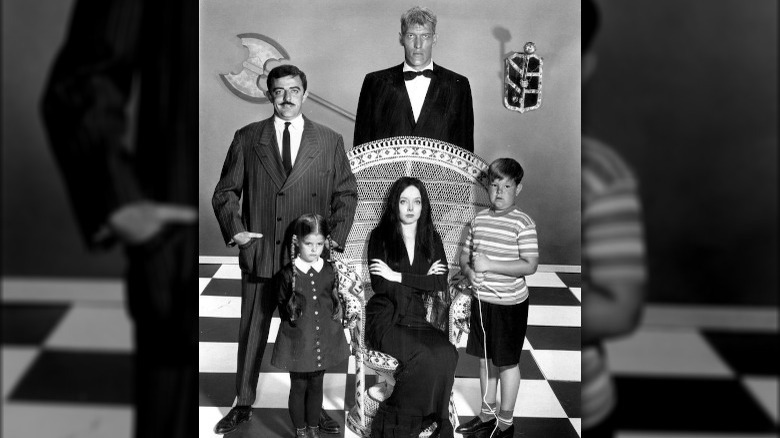

Everyone knows the song: In fact, it's quite possible that it's one of those shared, collective memories that people are just born knowing — even if they've never seen any of the 64 original episodes of "The Addams Family."

If that's the case, that's a shame. Sure, the family is a little non-traditional ... although, who wouldn't find having an extra hand around the house to be, well, handy? While they might have a pet lion, a rack in the basement for anyone who happens to need a really good stretch, and the occasional torture device laying around, there's something else there, too: A family that loves each other, and parents who really, really love each other.

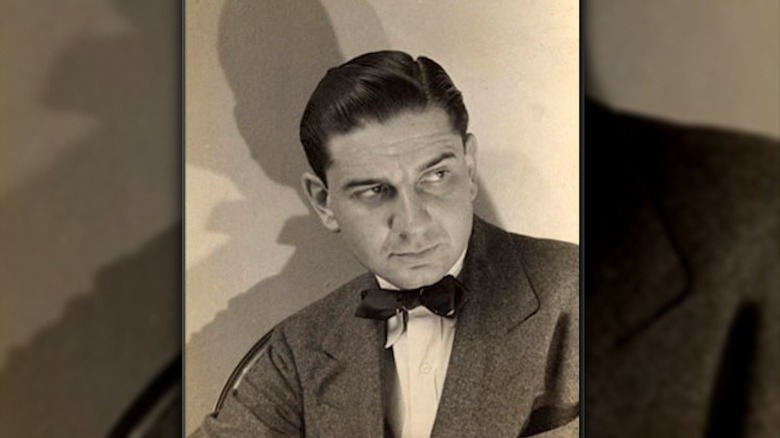

The New York Times reports that The Addams Family started out as cartoons published in The New Yorker, and they were the brainchild of an artist named Charles Addams. The cartoons, which ran for around 50 years, were only a small portion of his work. When he died in 1988, his obituary shared this sentiment from The New Yorker editor Robert Gottlieb: "Charles Addams has been someone whose work we instantly identify as central to The New Yorker," and "I can't imagine the magazine without him."

So, who was he? He was a predictably fascinating character in his own right.

He had a perfectly normal childhood

Charles Addams was born in New Jersey in 1912, and told his biographer, Linda H. Davis (via Smithsonian Magazine): "It would be more interesting, perhaps, if I had a ghastly childhood — chained to an iron bed and thrown a can of Alpo every day. But I'm one of those strange people who actually had a happy childhood."

His nickname growing up was "Chill," and even though he had a perfectly normal childhood — an only child and the apple of his parents' eye — his obsession with the macabre was there early. The Long Island Press says that he was just 8 years old when he started wandering into a local abandoned Victorian mansion and started drawing skeletons on the walls. It wasn't just a conveniently abandoned place to explore, either: "I was always aware of the sinister family situations behind those Victorian facades," he told Davis via the Long Island Press.

Scaring people became a favorite pastime: One of his go-to pranks was hiding in the dumbwaiter of his childhood home and jumping out to scare his grandmother. But amid his fascination for Halloween tombstones and cemeteries were his artistic endeavors. His father — a piano salesman — encouraged him to draw. That, says The New York Times, led to him getting his start drawing cartoons for the school paper, which turned into studying at Colgate University, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Grand Central School of Art.

Addams got his start working with images of corpses

The work of Charles Addams was most associated with The New Yorker, and according to The New York Times, he hadn't expected to get his first drawing commissioned by the magazine. The one that was selected was an illustration of a man standing on ice, looking down at his stocking-clad feet with the caption, "I forgot my skates."

But according to biographer Linda H. Davis (via Den of Geek), he got his first real job as an artist elsewhere: at the magazine True Detective. There, he was able to hone some of his technical skills as he cleaned up the images of bloody corpses for publication. But Davis stressed that the morbid nature of the work didn't impact or shape his imagination in any way. Rather, he was suited to the work because he was already a little off-kilter. "He was really born with that imagination," Davis said.

Charles Addams' ideas came from watching those around him

When it comes to the questions asked of creative types — whether the person is an artist, a writer, or a musician — everyone always wants to know where their ideas come from. Especially ideas that are so dark.

Addams was fond of saying that many of his ideas were sparked by the people he saw: In addition to claiming that his time at the Grand Central School of Art was mostly just spent people-watching, The New York Times says he would later have a favorite place to sit: Near the Plaza Hotel and the statue of General William Tecumseh Sherman (pictured).

But interestingly, not all the ideas he drew were his own. According to The Washington Post, Addams style had become so synonymous with The New Yorker that on occasion, other artists would submit great ideas that they would purchase and give to Addams to illustrate. There were many submissions, too, but Addams condemned many as "too grotesque, too ghastly," for him, clarifying: "Death is more of a cozy feeling in my work, I suppose."

One person, in particular, was relentless in sending Addams ideas, but not a single one was ever used. "There was a minister in North Carolina who sent me stuff for years," Addams recalled. "It is remarkable how tasteless this minister's ideas were."

He had some non-traditional ideas about his own family

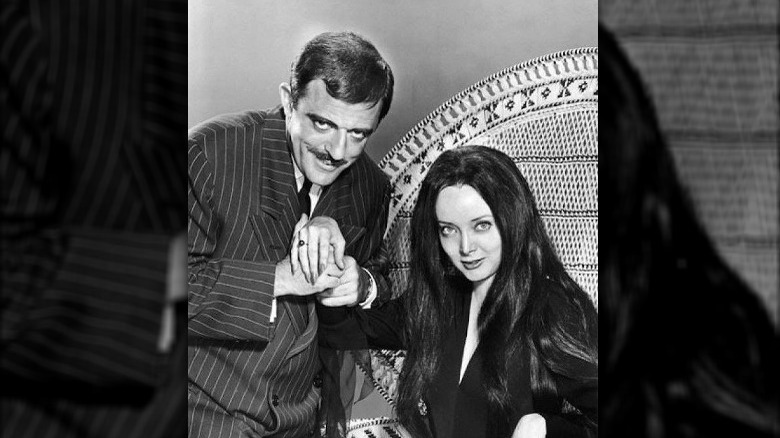

The first appearance of the then-unnamed Addams Family would be in the Aug. 6, 1938 issue of The New Yorker. Morticia and Gomez Addams (pictured) would become famous for their fiery romance, but in real life, the love life of their creator was no less fiery — albeit definitely less monogamous, says Observer.

Addams was married several times, first to Barbara Jean Day, then to a woman who went by the name of Barbara Barb (who he called Barbara II), and finally, to Marilyn "Tee" Matthews Miller, who he remained with until his death in 1988. While the official reason for the end of his first marriage was a disagreement over whether or not to have kids (he firmly said no, says MeTV), there were also signs that fidelity was at play — including a datebook, where he kept brief notes on all the women he had affairs with.

When Linda H. Davis used the datebook and interviews to reveal (via Den of Geek) some of the sordid details of his personal life in her book "Charles Addams: A Cartoonist's Life," some surprising names popped up. Specifically? Greta Garbo, Veronica Lake, Joan Fontaine, and Jacqueline Kennedy.

It turns out that when "The Addams Family" premiered, Addams was having a real-life fling with Jackie Kennedy (and yes, it was just a few months after JFK's assassination.) It didn't last long, but Davis says that they remained friends after the romance was over.

Did Charles Addams' wives inspire Morticia? Not quite

It's often said that Charles Addams modeled Morticia after his real-life wives, but it turns out that's not exactly true. It was the Vanderbilt Cup Races who debunks this theory, and it's not as weird of a thing as it seems at first glance — Addams, says the Observer, was a massive car guy who was fond of telling people that his 1926 35C Bugatti was the same model that the dancer Isadora Duncan was driving when she was killed.

The Vanderbilt blog showed a photo of Addams and his first wife in a 1927 Mercedes and repeated the oft-told tale that she was the inspiration for Morticia. About a year after the blog post, they added a correction from H. Kevin Miserocchi, the Executive Director of the Tee and Charles Addams Foundation. He clarified that although there were photos out there of Addams drawing his wives as Morticia, the character dated back to 1933 — long before he was married.

MeTV adds that it was his second wife, Barbara Barb, who ended up taking Morticia — and the other members of the Addams Family — for herself. Barbara, the story goes, asked Addams to take out a life insurance policy on himself. His legal advisors told him that wasn't wise, and he filed for divorce in the aftermath. In the rather acrimonious relationship, she ended up getting control of the television show and all the franchise rights.

During WWII, Addams made training films and offended the Nazis

For what would have been his 100th birthday, Charles Addams got his own Google Doodle — and if there's any sign that someone's made it, that's it. The doodle was published in conjunction with the Tee and Charles Addams Foundation, and when Wired did a brief look back on his life, they reported that he had been working right through World War II. That's when his skills as a cartoonist were put to a different use: creating training films for the military.

Biographer Linda H. Davis says (via Den of Geek) that he was also offending the Nazis.

Addams cartoons were wildly popular in Europe, particularly in non-English-speaking countries, says The Washington Post. Why? Many had no captions — or short, easy-to-translate captions — which meant they were funny to everyone, no matter what language they spoke.

Except, Davis says, one particular cartoon that gained him the ire of the Nazis. She said that the one they were wildly horrified by was one where one of the Boy Scouts opened a door to see his father preparing a noose. The caption read, "Hey, pop, that's not a hangman's knot." Davis said, "The Nazis were offended by it. And I'm sure that made his day."

His political leanings are on display ... if you know where to look

When John Astin was cast as Gomez in "The Addams Family" television show, he had some doubts. He told The Baltimore Sun (via Decades) that he almost didn't take the part because he didn't have faith in himself that he'd be able to pull it off: "I didn't want the characters to come off like ghouls or monsters. Addams cartoons are almost indescribable — except to say, 'It's Addams.' They imply violence, yet they're not violent. They somehow permit a person to release aggressive feelings without feeling guilty."

Astin looked absolutely nothing like the character from Addams cartoons, and it was the Smithsonian that observed the fact that casting a lookalike would be impossible: The original looks more like a sort of man-pig than someone 100% human. They add that he was inspired by the old-timey movie bad guy Peter Lorre, but according to Time, there was something else going on there, too.

Addams, it turns out, was a lifelong Democrat — and when it came time to create the patriarch for his spooky family, he decided to make the then unnamed man-pig a striking resemblance to New York's Republican governor Thomas E. Dewey.

Yes, Addams home is as creepy as anyone could hope

In 1982, The Washington Post visited Charles Addams at his midtown penthouse and quickly learned that fans of "The Addams Family" and admirers of their home (pictured) wouldn't be disappointed. The centerpiece of Addams real home was an embalming table dating to the Civil War and still sporting some rather suspicious stains. Addams, says MeTV via The Charlotte Observer, had the whole thing covered with glass so it could be used as a coffee table. The walls were covered in medieval weapons — he had a particular love for crossbows — and when it came time for him to pour himself a drink, it was poured into a goblet. There was a ton of taxidermy, too, including snakes and piranhas, as well as anatomical figures with removable organs.

A longtime fixture was his dog, Alice B. Curr — even though Addams said he only adopted her for a very specific reason: "They told me that this dog hated children, and I said, 'Great. I'll take it.'"

And yet, NPR says that as much as Addams delighted in seeing the reactions of guests when he showed them some of his stranger treasures — like a human thigh bone — he also had a soft spot for some of his fans. He befriended one fan who had been disabled by meningitis and was known to take the disabled brother of a friend for rides in his Aston Martin and Bentley.

Charles Addams drew about what he was afraid of

NPR says that of all the people who knew Charles Addams, they all pretty much agreed on one thing — he wasn't nearly as scary as those who didn't know him expected. While it was true that he didn't smile — giving rise to the rumor he had fangs — he once told a friend that he didn't smile because he had seen the photos, and thought that he "looked so evil, he couldn't stand it." He even drew comparisons between his own appearance and that of Uncle Fester, and asked those who knew him to describe him "as having the faint scent of formaldehyde."

It's this sort of dual personality that biographer Linda H. Davis says (via NPR) gave Addams and his work not just popularity, but longevity. While the darkness made his work stand out, it was the content that made it stay: Addams depicted things that terrified him, and that terrified a lot of people.

"He laughed at things that are scary and defused his own fear, and defused ours in the process," Davis explained. Addams spoke openly about his own fear of snakes and his own claustrophobia, and drawing them made them not-so-scary for him and his audience. His themes are universal — death, love, loss, family, and fear — and by collecting his memento mori and turning the end of life into what he called "a kind of cozy condition," he did the same for his audience.

The Addams Family is a miniscule part of his work

According to the Smithsonian, Charles Addams now-famous family is only a tiny fraction of his work. There were only 58 Addams Family cartoons, and overall, Addams did around 1,300 for The New Yorker alone. It's surprising just how small a portion of his work they were, and here's some food for thought: Although most of the cartoons ran in the 1940s and '50s, the characters didn't even have names until the television show aired in the mid-60s. Even then, the names weren't the ones that Addams wanted. He had campaigned for "Repelli" instead of Gomez, and "Pubert" instead of Pugsley.

Today, Addams originals are housed in galleries like the Library of Congress and The New York Public Library. And others? According to Swann Auction Galleries, they can command a pretty penny. One — of Lurch showing a shocked guest to his room — was valued at around $20,000, while another — of a scuba diver approaching a sunken galleon that had light streaming through one window — came in at a respectable $16,250. Even lower-value works sell for over the estimate: Addams erstwhile traveler finding himself on the bank of the River Styx had an estimated value of between $4,000 and $6,000 and ultimately sold for $7,250.

Addams, on the other hand, has confirmed (via The Washington Post) that he received just 4% of the gross, first-run profits from "The Addams Family" TV show, which amounted to not much at all — and no residuals.

One of his comics helped kick-start the investigation into women in the history of computing

Today, the world is starting to recognize the contributions of women in fields like computing and aeronautics, but for a long time, these scientists, mathematicians, and programmers were overlooked. According to Silicon Republic, some of the inspiration to rediscover them came from an odd place: Charles Addams.

In 1961, Addams did a cover for The New Yorker that showed a mature, grandmotherly-type woman sitting at the sort of massive computer bank that was the norm back then. The computer spits out a Valentine. Isn't that cute? Sure is!

Only, it was much, much more. Kathy Kleiman is now the founder of the ENIAC Programmers Project, which is dedicated to finding and preserving the stories of long-forgotten female programmers — and, in turn, promoting STEM fields to modern women. She was an undergraduate when she questioned why men in photos of the first computers were identified but women were not, and was told that they were models. They were not — they were programmers.

Addams cartoon is credited as being one of the pieces of proof that at the time, it was widely known — and accepted — that women were involved in computer science, the development of technology, and programming. What happened in the meantime is a very long story, but Addams? He may not have known how important that cover would be — particularly to the women who were forgotten for too long.

Addams wife's official statement after his death was cartoon-worthy

Charles Addams passed away in 1988. According to his obituary in The New York Times, the 76-year-old had been sitting in his car outside of his Manhattan apartment building when he had a heart attack. He was rushed to the hospital but died on arrival.

Addams was married to his third wife at the time, and her official statement was something that pretty much summed up why they were a couple: "He's always been a car buff, so it was a nice way to go," she observed.

They had been married for eight years — after tying the knot in a pet cemetery — and had suggested that such a cemetery would be a fitting final resting place for them both. It would be far from the first he'd found himself in, as he often talked about how if he found himself in a city or town with a graveyard, his feet would just sort of take him there.

Addams, though, had something else in mind for when he died: According to The New York Times, he and his wife had attended a funeral when he told her, "Don't ever do that to me." In accordance with his wishes, she didn't. Instead, she held a 250-person party at the New York Public Library to celebrate his life and legacy. Since she had worn black to be his bride, she donned white as his widow.