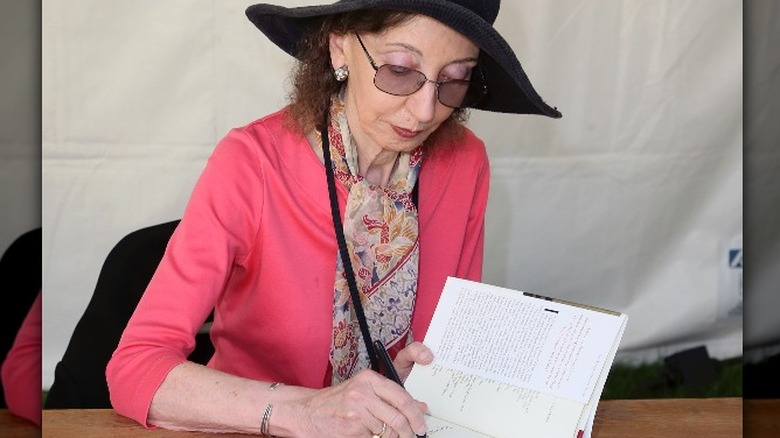

The Untold Truth Of Joyce Carol Oates

Famous artists get shoehorned into the same tortured mold: impoverished, addicted, mentally ill, and prematurely dead. Whether writers, painters, sculptors, actors, or musicians, there's a mythos about the most talented flames burning out in a hail-fire of misery. Think Vincent van Gogh, Sylvia Plath, Kurt Cobain. Even Aristotle perpetuated this legend, writing, "No great mind has ever existed without a strain of madness," per The Independent.

But critics of the tortured artist topos have also emerged, like A.L. Kennedy writing for The Guardian. Elizabeth Gilbert dedicates much of her book, "Big Magic: Creative Living Beyond Fear," to refuting the concept. And the Antithesis Journal notes that psychological imbalances hamper, rather than stimulate, creativity. One author who shatters the tortured artist stereotype is Joyce Carol Oates. Never one to shy away from uncomfortable and even painful experiences in her writing, she also fails wildly at being the tormented soul.

Elaine Showalter, a critic and friend of Oates, explains, "She's not an alcoholic, not a drug addict, not crazy, she has no broken marriages — it's a visceral superstition, that to get away with this she must have a pact with the devil" (via The Guardian). While Oates may not demonstrate madness, this hasn't precluded her from experiencing hyperbolic criticism. And it should be noted that the brilliant author of "Blonde," while functional and healthy, is anything but ordinary. Keep reading to learn more about the untold truth of Joyce Carol Oates and why she continues to stir up controversy.

Violence marked Joyce Carol Oates' early experiences

In "They All Just Went Away," Joyce Carol Oates asks, "Shall I say for the record that ours was a happy, close-knit and unextraordinary family for our time, place and economic status?" Despite this inquiring characterization, the black tendrils of violence held her family tightly (via The Guardian).

She grew up in rural New York state's Millersport, a settlement of scattered farms, a minor stream, and some abandoned houses. Populated by working-class people and immigrants, Joyce Carol Oates was the first member of her family to finish high school. As per The New Yorker, eventually, she graduated from Syracuse University as valedictorian. Higher education permitted her to escape the hard and mean life of her ancestors. But shaking off the family stories proved more difficult. They gouged deeply into her psyche as her more autobiographical writings attest.

Her paternal grandmother, Blanche Morningstar (nee Morgenstern), survived her father's attempted murder of her mother and his successful suicide, according to Greg Johnson's "Invisible Writer: A Biography of Joyce Carol Oates." And Joyce Carol Oates' mother never knew her father, Stephen Bush, because he died in a tavern fight when she was just a baby. This left Joyce Carol Oates' maternal grandmother to care for nine children alone, a total disaster. As a result, Joyce Carol Oates' mother would be given away. Her dad, Frederic Oates, never knew his father and had to drop out of school to support his family. Violence and class struggle were woven into the fabric of the author's youth, providing harsh and unforgettable lessons.

She witnessed abuse in her youth

Joyce Carol Oates' writing explores childhood abuse, awash in a sea of cruelty and violence. Her novel, "Marya: A Life," follows an 8-year-old girl who faces sexual predation at the hands of her 12-year-old cousin. This horror mirrored real-life terrors whispered about in the community where she grew up. Oates recalled in an interview with Greg Johnson, "So many brutal, meaningless acts ... incredible cruelty, profanity, obscenity ... even (it was bragged) incest between a boy about 13 and his six-year-old sister ... things done to animals," as quoted in "Invisible Writer: A Biography of Joyce Carol Oates."

Other books from "The Molesters" to her own memoir contain threads of the victimization Oates saw occurring among the youth of her community. "I've sometimes been criticized for the violence in my writing but it was really not that unusual in my background," she said to NPR. "I wasn't imagining or inventing any of these things." From watching an abusive neighbor to the local farmboys harrassig and assaulting all the local children. "It was so saturated in that way of life that there was no expectation of anything different. ... It didn't break me or wound me. I basically just accepted it," she said.

The deep current of extreme violence (often sexual) found running through Oates' writings is far more than merely gratuitous. It remains part of her lived truth. Throughout her life, Oates has used writing as a therapeutic outlet to better examine these experiences and their implications, a topic she fleshes out more fully in her essay, "Running and Writing."

Joyce Carol Oates' work explores victimhood

Over the years, Joyce Carol Oates' stories have attracted both praise and deep-seated hate, as reported by The New York Review. Book reviewer Caroline Fraser argues that part of the reason for this is Oates' veritable obsession with victimhood, violence, and the destruction of innocence — themes threaded throughout her novels, novellas, short stories, and poems.

As Fraser explains, "Oates' primary subject is victimhood, and her work features a kind of Grand Guignol of every imaginable form of physical, psychological, and sexual violence: rape, incest, murder, molestation, cannibalism, torture, and bestiality." Interestingly, this unfaltering focus on the worst that life can possibly throw at a person (often a young, naïve girl) may be at the dark center of much of the contemptuous criticism Oates has faced over the decades. Some of the criticism has been downright violent, with people like Truman Capote calling for her punishment by death.

One of the most unsettling aspects of Oates' writing is the point of view she sometimes chooses. In works like "Marya: A Life" and "The Molesters," she broaches the abuse from the point of view of the innocent victim. As a result, Fraser notes the reader is swept along in the grooming and perversion without the ability to stop it. In essence, this leaves the reader feeling equally victimized. It's a powerful narrative choice, but one that not all audiences may appreciate.

Her writing exudes compassion for adolescent girls

At the heart of Joyce Carol Oates' writing is a deep understanding and compassion for adolescent girls, as reported by The Guardian. Oates has admitted in interviews that she feels a tremendous connection to young people and the discoveries they must make as they grow spiritually, emotionally, and intellectually. Her work gives teenaged girls a newfound voice and respect.

Russell Banks, a fellow novelist who teaches with Joyce Carol Oates at Princeton, notes, "[Oates is] unique in American literature in her compassion and understanding of adolescent girls. She has made them memorable — humanized and dignified them," as quoted in The Guardian. Exploring the innocence, emotions, and briefness of youth remain constant subjects within her writing. Without realizing it, this consistent focus helped prepare her to write "Blonde," an exploration of an adolescent named Norma Jeane (pictured) and her transformation into Marilyn Monroe.

Monroe's destruction takes place before the eyes of the world (via The New Yorker). When it's complete, glimmers of the previous Norma Jeane (the spelling used in "Blonde") prove almost non-existent. It's a frightening exploration of the machine that destroys and dismantles adolescent girls rendering them valueless apart from their sexuality. These are tremendously important stories to tell, and Oates realizes they bear repeating. Her writing lays bear the vast gulf between the American Dream and its reality, per Literariness. This may not be a theme everyone wants to acknowledge, let alone explore.

Joyce Carol Oates wrote a defense of her work

Joyce Carol Oates' essay, "Why Is Your Writing So Violent?," appeared in The New York Times on March 29, 1981, exploring the titular question. She described getting asked this in Warsaw, Poland. Ironically, the prompt came at a spot where 200,000 Poles died in 1944 at the hands of the Nazis, a point she makes clear in her defense. The reminder underscores the inescapable premise that human violence is not an invented impulse by a self-indulgent writer but rather an echo of unpleasant realities. As she explains in her essay in the Times, "The serious writer, after all, bears witness. ... reality is always the foundation."

Nevertheless, people have had plenty to say about Oates' work over the years, per The Guardian. She's often either loved or hated. In "The Faith of a Writer: Life, Craft, Art," she explores why: "Art by its nature is a transgressive act, and artists must accept being punished for it. The more original and unsettling their art, the more devastating the punishment."

In this essay, Oates comes to fascinating conclusions about the utility of the criticism she has faced. In a nutshell, she argues that the criticism has forced her to dive more deeply into her imagination and inner-self while seeking solace. This has, in turn, led to the plumbing of even greater depths of creativity and inspiration. Naturally, there's a certain truth in the concept of a writer retreating into herself as a device of protection. And if her life's work is any indication, this approach has panned out well for her.

She's taken the literary road less traveled

Joyce Carol Oates is as voracious a reader as she is a productive author (via The Guardian). Her diverse sampling of literature has colored her prose while setting her on a path of collision with the literary world over the last few decades. Or, as literary critic Leo Robson for The New Yorker puts it, "In an era that fetishizes form, Oates has become America's preeminent fiction writer by doing everything you're not supposed to do." And she shows few signs of slowing down.

A staunch defender of long novels, she has railed against characters like R.P. Blackmur who pioneered the 1934 revival of Henry James' work. Individuals who fall into this James camp criticize the masterworks of novelists like Fyodor Dostoyevsky as "loose baggy monsters." But Oates has argued in defense of this Russian literature, arguing that individuals like Blackmur, far from convincing readers of their point, merely evidence their own narrow outlook.

She argues that they lack the ability to perceive, let alone appreciate, the structure of longer novels, making due with superficial concerns of form like unity of tone and symmetry. Oates has had support in her opinions on meandering literature. At various points, authors like Iris Murdoch and Anne Tyler have joined her ranks. But Oates remains one of the last authors standing when it comes to an esthetic some feel is outdated.

Her great productivity has attracted haters

Critics often find fault with Joyce Carol Oates' tremendous productivity (via the New York Times). She doesn't fit into the mold of the suffering alcoholic novelist whose best work is their only work. So many have opined over her voluminous writings that it's become a sore point in interviews, according to The Guardian.

For starters, nearly every book review about Joyce Carol Oates has to take a jab at her prolific body of work. Like a body count, reviewers throw out the ever-growing number as if astonished by its obscene audacity (as seen in The New York Review). Perhaps this feeling of revulsion towards so great a literary contribution has more to do with envy (think Julia Cameron's "shadow artists"), but that's a subject for another time.

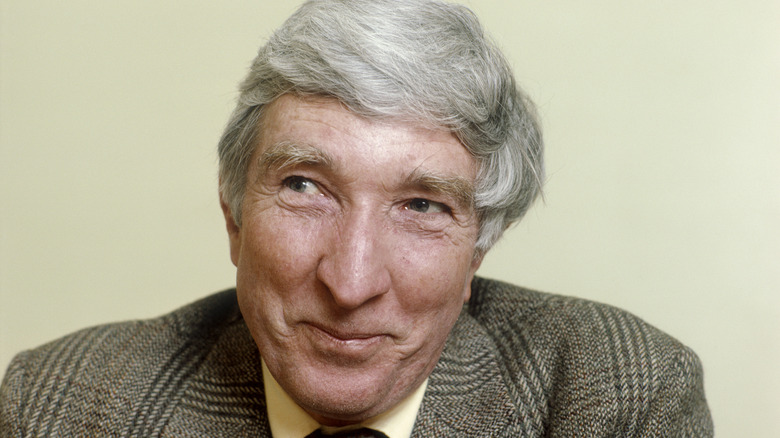

John Updike, Oates' friend and fellow writer, points out, "The writers we tend to universally admire, like Beckett, or Kafka, or T.S. Eliot, are not very prolific. The small choice body of work is what we like and instead we get Joyce Carol Oates' Victorian productivity, without the Victorian audience. She is, in a way, out of her time" (via the Guardin). As works like "Blonde" attest, she doesn't appear in any hurry to alter her approach to writing and what it produces, no matter how singular it appears in today's world. During a book chat with CNN, she admitted the text for "Blonde" originally came in at 1,400 pages, forcing her to cut 400 pages to make it manageable and publishable.

Joyce Carol Oates' work focuses on the worst possible outcomes

Another criticism lobbed, sometimes well-meaningly, at Joyce Carol Oates is the drive of her story-telling vision towards the what-ifs of life, usually veering towards the path of greatest devastation (via The New Yorker). Fellow writer, John Gardner, explains how he once asked Oates to write a story where the what-ifs go right instead of wrong. But what followed were more dark clouds, something Henry James referred to as "the imagination of disaster."

Some of Oates' bent towards the worse-case scenarios appears to stem from how she has coped with her sister's severe autism and institutionalization, according to The Guardian. Oates' sister, Lynn Anne, was born on the author's 18th birthday, and her handicaps appear to have had a dramatic impact on Oates' outlook. Although the two sisters share a startling resemblance, Lynn Anne has never uttered a word. Such jarring contrasts in their different circumstances has invited Oates to speculate on unanswerable life questions, like luck and fate.

Perceiving her life on this precarious footing has made Oates unflinching in the face of the worst possibilities. It also makes her prose uncomfortable and filled with emotional landmines. But while her fiction tends to dwell on unfortunate outcomes, she does so with an unfaltering lack of self-pity and creativity.

Truman Capote hated her

Reasons abound for why Joyce Carol Oates' work has been trashed by critics over the years, from the hurried nature of her prose to the simple fact that she's a woman (via The Guardian). In fact, the vitriol her writing has inspired is legendary in its own right. Among her most vocal critics have been Truman Capote, James Wolcott, and Michiko Kakutani, a book critic with The New York Times.

Capote stood apart in his utter contempt of Oates: "She's a joke monster who ought to be beheaded in a public auditorium. As for Wolcott's criticisms of the verbose author, they are epitomized in his essay for Harper's Magazine titled, "Stop Me Before I Write Again." The titular imperative gives voice to a fictional Oates, taking yet another jab at the productivity that incites both envy and rage.

Kakatuni has also published his own colorful diatribes against Oates and her work, according to CNN. Fundamentally offended by her style and approach to fiction, he has branded her novel "Blonde" as disordered, bloated, and "the book equivalent of a tacky television mini-series." Fortunately, Wolcott and Kakutani left the calls for public execution to Capote.

An unlikely subject for Joyce Carol Oates

You'd think the award-winning novelist of "Blonde," an exploration of Marilyn Monroe's inner life, fostered a lifelong fascination for the platinum starlet. But, according to The Guardian, nothing could be further from reality. Oates had little interest in Monroe and wasn't especially driven to find out more about her. But everything changed after the author stumbled across a photo dated 1941 (via The New Yorker).

The image shows Norma Jean Baker in her pre-fame days, the winner of a minor beauty contest in California. The fresh-faced and innocent teen left an indelible impression on the author: "I felt an immediate sense of something like recognition; this young, hopefully smiling girl, so very American, reminded me powerfully of girls of my childhood, some of them from broken homes," as quoted in Greg Johnson's "Blonde Ambition: An Interview With Joyce Carol Oates."

Inspired by glimmers of this nearly unrecognizable yet disarmingly authentic side of the future Monroe, Oates dove headlong into research. Thirsting to find out more about the ingenue's transformation into a Hollywood bombshell, her writings on the topic soon ballooned into a full-blown novel, exploring the fictionalized psychological turmoil of the star-crossed performer. Two decades after its publication, "Blonde" made its way to the big screen in 2022 via Netflix with Ana de Armas playing the platinum protagonist. The film represents a crowning achievement for one of America's most productive and controversial authors and one that she has heartily praised, per the Independent.