Bizarre Things That Happened At The Eiffel Tower

Seeing pictures of the Paris cityscape pre-Eiffel Tower is just weird. It could be any old city from a distance. Now when shown a picture of France's capital, everyone would know what place they were looking at, thanks to the iconic structure. (Unless the picture was of the duplicate Eiffel Tower in China, which looks so much alike it kind of blows your mind.)

For more than a century, the Eiffel Tower has been an almost sacred part of Parisian identity. It wasn't always like that, though. It's been a weird, rocky road for this landmark.

The Eiffel Tower was used as a really big antenna

The Eiffel Tower isn't just another pretty face; it played an invaluable part in World War I. In 1903, Gustave Eiffel invited radio researchers to set up in the tower, and funded research himself. According to Science News for Students, it was about five years before the Tower became a central hub for a communications network that could reach North America, and that's when the military got interested. The Tower became a permanent military radio base and was used to intercept German radio communications.

That included ones sent by the German troops advancing on Paris in 1914. When the French learned the Germans were delayed, they started shuttling troops to Marne. If you remember your history, the battle at Marne saved Paris from German occupation.

Two years later, the Tower station intercepted another German message on the way to Spain. It referred to a spy called "Operative H-21," and with the message, they tracked the code name to Dutch dancer Mata Hari — and arrested her. The Tower was such an important communication hub, the French military even ordered it outfitted with explosives so they could destroy it if it was at risk of falling into German hands. Fortunately, that never happened.

The Eiffel Tower was called a ton of nasty names

What sort of words would you use to describe the Eiffel Tower today? Elegant? Graceful? Even delicate? That's not what people thought when it started going up. Paris almost had an emotional meltdown over the monstrosity that would be silhouetted against their city skies.

The Tower was officially opened at the World's Fair in 1889. It was built for the fair and was only meant to stand for a few years. As far as most people were concerned, that was a few years too many.

Vox compiled some of the reactions to the Tower. If it were a person, there would be some seriously hurt feelings. Writer Guy de Maupassant wrote it was a "giant ungainly skeleton upon a base that looks built to carry a colossal monument of Cyclops, but which just peters out into a ridiculous thin shape like a factory chimney." That's what passed for hate in 19th-century France, and it's not the worst. Poet and novelist Francois Coppee called it "incomplete, confused and deformed," but our favorite comes from novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans. He called it "a hole-riddled suppository," and once you see it, you can't unsee it.

Citroen turned the Eiffel Tower into a massive advertisement

It's easy to lament the commercialization of almost everything in the 21st century, but really it's always been that way. Those who already hated the Eiffel Tower must have loved the day it became the biggest billboard ever, lit with more than 250,000 bulbs and 370 miles of wiring. All that equipment, says Autocar, was used to cover three sides of the tower with the word "Citroen."

The car company rented out space on the Eiffel Tower from 1925 to 1934, and we can't even imagine what the electricity bill must have been. Each letter was 92 feet tall because go big or go home. As if turning the Tower into a flashing billboard wasn't weird enough, the advertising signage played a part in another big world event — it guided Charles Lindbergh toward the airport at the end of his 1927 trans-Atlantic flight. No word on whether or not he bought a Citroen once he landed.

Eiffel saved his tower with science

Just getting the Tower built was part of the problem, and Science News for Students says it was so hated that Gustave Eiffel needed to make it an invaluable piece of Paris's landscape if he wanted to keep it standing. He did that by making it a hub of scientific research, not wasting a bit of time before installing a weather station on the Tower the day after it opened. It was directly wired to France's weather bureau, and next came a giant manometer that stood the height of the Tower. Manometers are used to measure pressure of liquids and gases, and the size of the Eiffel Tower meant it could support a manometer big enough to measure pressures 400 times what had been measured before.

In 1903, Eiffel started conducting experiments in aerodynamics, inspired by the work of the Wright brothers. He developed formulas for wind resistance, work that led to the construction of a massive wind tunnel. With the addition of radio and communications equipment, the Tower became a key part of international timekeeping, broadcasting signals across Europe to help synchronize everything from clocks to travel schedules. That same information was invaluable to ships, too, who could use it to determine their longitude. The Eiffel Tower was the original GPS, atomic clock, and WeatherBug all rolled into one.

The Eiffel Tower has been a number of different colors

Sure, you've seen the Eiffel Tower, but have you really looked at it? If you've looked really closely, you may have noticed it's actually painted three different shades, dark at the bottom and lighter at the top. It hasn't always been that color. (Doctor Who, take note.) Going back in time would mean you'd see a very different Eiffel Tower, starting with a color the Eiffel Tower's official site describes as "Venetian red." After that, it was painted reddish-brown, and in 1892, it turned a rusty color they call ocher brown. That was short-lived, and in 1899 a seven-year repainting cycle kicked off with a fresh coat of yellow-orange at the bottom shading all the way to pale yellow at the top.

Yikes. It was yellow-brown until 1947, which should make you reimagine war-torn Paris a bit. The Tower turned brownish-red from 1954 to 1961, and 1968's paint job debuted the color now called "Eiffel Tower Brown."

Now, some fun facts about painting the Tower. It takes around 18 months, which actually sounds short when you learn that the 25 painters are required to paint the entire thing by hand. Yes, with a brush and a bucket of paint. They use around 60 tons of paint, and around 15 tons will erode away between paint jobs. It's a job both monotonous and terrifying, but as long as people keep doing it, the Tower's iron will last forever. Well, until the apocalypse.

Woman marries Eiffel Tower, gets heart broken

Now, we aren't here to judge. We are here to talk bizarre, though, and for those who aren't attracted to inanimate objects (a real desire that some people claim), Erika Eiffel's obsession with the Eiffel Tower is bizarre.

She's called Erika Eiffel because she married the Tower in 2007, after a decade-long relationship that culminated in a commitment ceremony (via Australian Broadcasting Corporation). A year later, she agreed to be the subject of a documentary called Married to the Eiffel Tower, and says that's when the relationship got rocky, Eiffel Tower staff stepped between the lovers and made it quite clear she was no longer welcome. The relationship had to end.

"I don't even know how to articulate a heartbreak like that. It just wrecked me," she said in a documentary. "It was this final blow, and I just had to withdraw." You'll be happy to know that she moved on. Her rebound from the Eiffel Tower (which is a "she," in case you're wondering) was the Berlin Wall. They bonded over mutual rejection, she said, and she's since moved on to a relationship with a tower crane.

An American pilot chased a German plane through the Eiffel Tower

Sometimes, you hear stories of people so badass you know they could carry an entire Marvel movie on their own incredible shoulders. William Overstreet was one of those people. The Virginia native headed to Europe during World War II, where he flew a P-51 Mustang underneath the Eiffel Tower's arches in the middle of a pitched battle with a German Messerschmitt Bf 109. Given that he was willing to go to those crazy lengths to end the fight once and for all, it's not surprising he ended up shooting down his target. What makes the story even crazier is that others have died trying to fly the same daredevil route, including Leon Collot in 1926 (via Perth's Sunday Times).

Jalopnik says the French Resistance fighters on the ground were so inspired by the sight he became something of a icon. Overstreet went on to fly eight missions during the D-Day invasion, and a series of secret escort missions after that. He was ultimately awarded the Legion of Honor when he was 88 years old. He passed away in 2014 at 92 years old, a total legend.

The discovery of cosmic radiation

At the turn of the 20th century, the science world had to be an incredible thing to be involved with. Scientists were experimenting with things like phosphorescence, X-rays, and uranium, but it turns out that "incredible" also meant "pretty deadly." Radiation was discovered, and Jesuit priest/professor Theodor Wulf was fascinated by the whole thing. He created new pieces of equipment for studying this groundbreaking stuff, and ran a series of high-altitude experiments to try to figure out just where nature's background radiation was coming from. There was a problem, though: The hot air balloons he was using had height, but they didn't have stability.

Wulf headed to what was then the tallest building in the world. According to Scientific American, he set up a series of experiments over four days. He measured radiation at the top of the Tower and at the bottom, and the height difference was enough to give him the first concrete proof that radiation was coming from the skies, not the Earth. Science is neat! People, on the other hand, are not, and Wulf's experiments went largely overlooked at the time.

An elephant climbed the Eiffel Tower

The circus is one of those things that sounds like a much better idea in the abstract than it is in real life. They're a cesspool of unhappiness and abuse painted with big top colors and cotton candy, and in the 19th century, the Cirque d'Hiver Bouglione Circus was the popular circus of Paris. EU Touring says it started out with a concentration on equestrian shows, but once the flying trapeze was invented, there was no looking back.

Circus shows ended during World War II, and in the years after the war, they were looking for bigger and better ways to get people back to the show. In 1948, they staged a promotional stunt that had to be all sorts of terrifying for the poor creature at the center of it all. They escorted their elephant to the first floor of the tower. She was the oldest in the world at the time, and the 85-year-old senior citizen climbed up the stairs. For her part, she showed great restraint in not throwing anyone over the edge when she got up there.

A Frenchman set a strange record

No one actually likes climbing stairs. That basic life truth makes it even stranger that in 2002, The Scotsman reported on a strange world record. Hugues Richard had gone up the Eiffel Tower's stairs, all the way to the first floor, in an impressive 19 minutes.

On a bicycle. Why? Because it's there, perhaps? His 2002 attempt actually halved the time of his earlier attempt in 1998. Then, he'd set the record with a 36-minute ride up the stairs. If you're wondering how the heck this works, he basically locks his brakes and hops up the steps. (You can watch him scale the Arc de Triomphe in the video above.)

Do some digging into Eiffel Tower history, and you'll find there's been a weird obsession with biking up and down it for decades. Cycling History says Pierre Labric rode his bike down from the first floor in 1923, and no one's entirely sure why, though it may have been a publicity stunt for his newspaper.

The Eiffel Tower moves

Here's a little weird science with your weird history. When the Eiffel Tower was built, LiveScience says, iron was still a relatively new building material. Until the Tower, it was an internal or industrial material, and this was the first attempt at making something that was really intended just to look nice. The unconventional building was an engineering marvel, even if that was overlooked by 19th-century trolls.

In order to build something that tall, they needed to account for the forces of Mother Nature. The Tower was built to sway, and The Local says the top will move as much as 5 inches in the wind. Weirdly, the sun can make it move even more than that.

As the iron tower heats up, it expands and can grow as much as 6 inches. It also moves away from the sun, and the top can tilt as much as 7 inches. That's a lot of expansion and contraction, and even though you might not feel it when you head up, it's knowing those fun little details that makes vertigo even more exciting to experience. You're welcome!

The ill-fated — and fatal — Eiffel Tower parachute demonstration

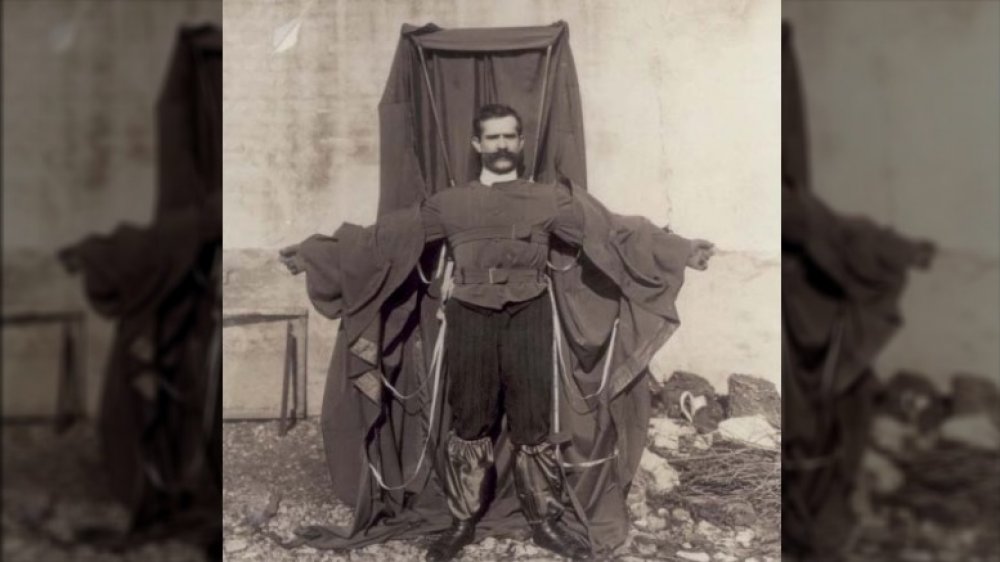

The general idea of the parachute goes back at least to Leonardo da Vinci, but it seems Paris has a special relationship with this life-saving (in theory, at least) invention. The first major parachute demonstration happened there in 1797, when Andre-Jacques Garnerin jumped from a balloon 3,200 feet above the city. His jump was successful (via History), but another inventor's jump from the Eiffel Tower was less so.

Franz Reichelt had a different idea for a parachute, and it was basically a flight suit with the chute attached. Think of something like a flying squirrel. The suit was filled with flaps that would deploy in case of emergency, but it didn't quite work as planned. According to Atlas Obscura, Reichelt tried numerous versions of the suit, first using mannequins, then using himself. He failed again and again — even breaking his leg when he jumped out of a window and fell 26 feet — but he wasn't deterred.

In 1912, he arranged to jump off the Eiffel Tower in front of a small group of the local press. Friends tried to stop him, but he went to the first deck — 180 feet up — climbed onto the guardrail, and jumped. Tragically, the suit didn't open. Reichelt was tangled in his invention and died on impact. He was almost immediately given the nickname the "Flying Tailor," because people are terrible.

A con man sold the Eiffel Tower for scrap

The Smithsonian calls Victor Lustig "America's greatest con man," and he certainly was creative when it came to crime.

In May of 1925, he headed to Paris and set himself up in the Hotel de Crillon. After commissioning some stationary that bore the official seal of the French government, he sent some letters to anyone who was anyone in the scrap metal industry. When they gathered for a secret meeting, he confided in them that the Eiffel Tower was being torn down because it had simply become too much to maintain and consequently, it was dangerous. The scrap was going to be sold to the highest bidder, and there was a lot at stake: 7,000 tons of metal. Lustig piled everyone into rented limos and headed to the Eiffel Tower to give them all a tour... and, to pick his mark.

That was Andre Poisson. He struck up a deal with Poisson, and promised that for just $70,000, he would make sure Poisson's bid was the winning one. Cash was handed over, and Lustig was almost immediately on his way to Austria. The swindle was never reported, and he even returned to Paris at one point, to try the con again with a different group of scrap metal dealers. He fled when he became pretty sure the police had been called, but his career wasn't over yet — he was only captured in 1935, and sent to Alcatraz.