The Untold Truth About LGBTQ+ People In The Wild West

In the Old West, there were two acknowledged genders: male and female. Today, however, we associate LGBTQ+ with a number of gender identities and sexual orientations. Human Rights Campaign says that LGBTQ+ stands for "lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer," plus "limitless sexual orientations and gender identities used by members of our community." Indeed, sexual diversity has taken giant leaps in the last 150 years. Back then, such terminology was unknown, and the now-offensive word "homosexual" wasn't even coined until 1869, according to the Independent.

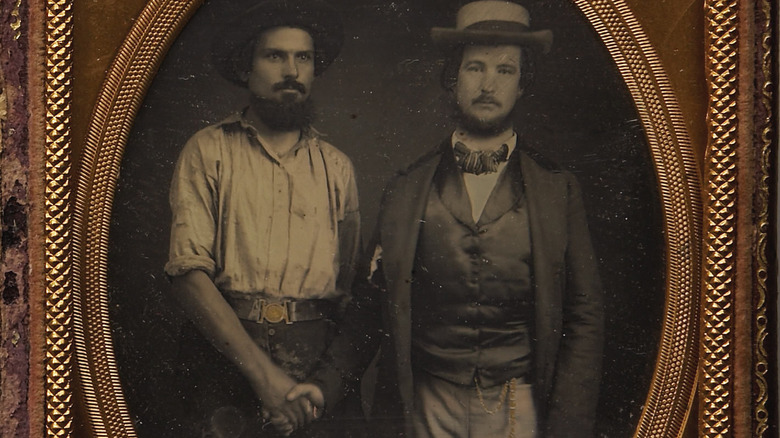

While people today have more rights when it comes to deciding which gender and orientation they best identify with, those who did so in the 19th century defied laws against them and engaged in same-sex relationships for a number of unique reasons. True West submits that being gay in the Old West was "common and so not a big deal." Certainly, though, folks didn't go around openly advertising their sexual identity. The book "Loving: A Photographic History of Men in Love, 1850s-1950s" by Hugh Nini and Neal Treadwell, submits that, for same-sex couples in the 19th and early 20th centuries, daring to take photos of themselves together "was not without risk" (via Rolling Stone). Read on for the untold truth of LGBTQ+ people in the Old West.

Early laws against LGBTQ+

Love, whoever it is for, is older than the stars. That would explain why America had anti-sodomy laws as early as the 1600s. "LGBTQ America," a book produced by the National Park Service, pinpoints specific laws against sodomy in several Eastern colonies between 1610 and 1656. Notably, these laws were aimed at men more than women. More laws would come, writes William Eskridge Jr. in his book "Dishonorable Passions," and many of them included capital punishment for violators. By the mid-1860s, at least some states removed the death penalty as other laws were passed against "indecent behavior," obscenity, and even cross-dressing (per "LGBTQ America").

The Comstock Act of 1873 prohibited the "mailing of obscenity," but also inspired a slew of laws directed at gay people and other marginalized communities. The laws illustrate how governments chose to handle LGBTQ+ persons in their midst, says the American Psychological Association. Authorities who were uneducated about same-sex love struggled with ways to address it. Notable too is that only the male population continued being targeted by the new laws, as well as the eventual homophobia that took root across America. Apparently it didn't occur to anyone that women could also engage in relationships with each other. In fact, says History, "intense and romantic friendships" among women were not only common, they were socially acceptable and sometimes even encouraged.

The lack of women in the West

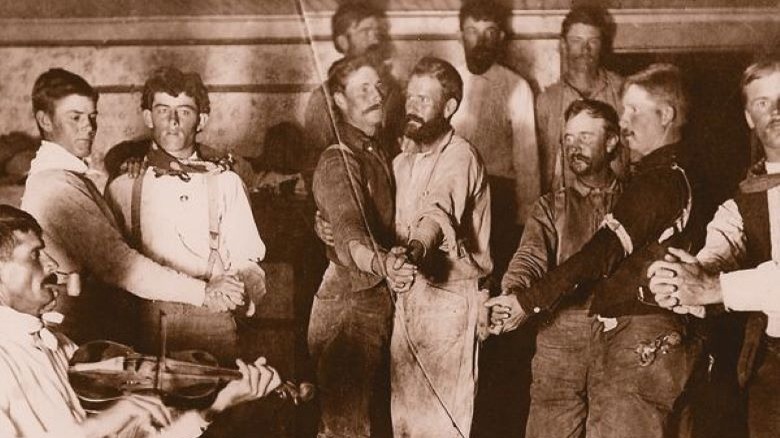

According to the 1870 census, each of the Western states — Arizona, California, Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and Wyoming — showed a larger population of men versus women. The difference in numbers could be drastic; in the area of South Park, Colorado, during the late 1800s, the ratio was 10,519 men to just 91 women, per "Red Light Women of the Rocky Mountains." According to True West, men going west without their female companions were forced to share not just domestic duties, but also social activities. At dances, men would sometimes tie handkerchiefs on one arm to denote them as the "female" partner.

Author and Old West researcher Deborah Hufford submits that same-sex relationships among men in the West were acceptable since there were so few women. Men working as farmers, loggers, miners, and ranchers in remote places found themselves with no other choice for romance. Sharing a small cabin with another man often meant sharing a bed, and there apparently was no shame in it — the exception being the rarely publicized sex crime. Dr. Thomas J. Noel's article in the Social Science Journal tells of an 1885 incident in Denver, wherein an older man promised a young man room and board, only to rape him.

The life of a lonely miner

The male pioneers of the West often found their surroundings desolate and lonely. Although Time points out that Native and Mexican women were among those populating the West, they were a rarity in places like the Rocky Mountains where mining was taking place in high altitudes. These barren, remote places made it extremely difficult to attempt much in the way of domestic living. As related in "Brothels, Bordellos & Bad Girls: Prostitution in Colorado, 1860-1930," one early Denver pioneer told of men "running to [their] cabin doors" whenever ladies arrived in town, "to gaze upon her as earnestly as at any other natural curiosity." According to Legends of America, the introduction of sex work in the early West alleviated some of the men's loneliness, but those living in extremely rural areas had no such luxury.

With no other choice for romantic companionship, sexual relationships between men were "an acceptable thing to do," True West quotes author Peter Boag as saying. Boag explains that "all-men societies" existed without women in plenty of places, and in them, men in same-sex relationships were not "seen as homosexuals." Noted Western travel writer Bayard Taylor even went so far as to pen a gay love story, "Joseph and His Friend," in 1870. Was Taylor the first gay novelist? Main Line Today suggests he might have been, quoting Taylor's desire to "throw some indirect light on the great questions which underlie civilized life."

Men made do with bachelor marriages

In the Old West, men who shared an intimate relationship with one another were often referred to as being in a "bachelor marriage." Deborah Hufford defines the arrangement as one of convenience for two men wishing to live together as a couple. Public discussion of their relationships, however, has been largely avoided. The Journal of American HIstory explains that although same-sex couples have been recognized throughout history, few historians have cared to address their sex lives. By ignoring that aspect, the "contemporaries" of such couples could avoid facing the uncomfortable fact that sex between them was possible.

The Pride also theorizes that some scholars have swept connotations of sex in bachelor marriages under the rug, but they were certainly there. One poem, published in 1915 on the fringe of the frontier West's last days, talked of the love between two men that "was more than any woman's kiss could be." What little in-depth research there was in the early 1900s often ignored the idea that men-to-men unions included sex. And, it is highly unlikely that gay men talked of what went on behind closed doors. The few exceptions include William Drummond Stewart, whom Xtra confirms openly hosted "a big, gay, medieval-themed orgy" during a fur trade rendezvous (per William Benemann's biography "Men in Eden: William Drummond Stewart and Same-Sex Desire in the Rocky Mountain Fur Trade").

Women's suffrage and lesbianism

In her book "Women of Early America," author Dorothy A. Mays confirms that early sodomy laws appear to have applied only to men. There was, however, an instance in 1642 when a servant named Elizabeth Johnson was punished in Massachusetts for "unseemly practices betwixt her and another maid." In the West, however, lesbianism wasn't officially recognized until the late 19th century. Before that, lesbians like Katharine Lee Bates, who wrote "America the Beautiful" after visiting the top of Pikes Peak in Colorado, went unrecognized. Bates openly engaged in a relationship with Katharine Coman, says the San Francisco Bay Times.

Other gay women of the 1800s, reports Montecristo magazine, included poet Emily Dickinson (pictured) who shared kisses, and even her bed, with her sister-in-law Susan Gilbert. Then there was Pulitzer Prize winner Willa Cather, whom Autostraddle writes preferred the name "William" in college and lived with another woman for nearly 40 years. Another surprise? Susan B. Anthony, who championed women's voting rights and, according to Them, had at least two lady lovers during her lifetime: Anna Dickinson and Emily Gross. After Anthony died in 1906, they report, Gross was devastated. And although all of these women have long been recognized for their achievements, scholars have only recently begun to acknowledge that they were gay.

The evolution of the Boston marriage

While gay men in the 19th century had their "bachelor marriages," gay female unions would eventually be recognized as "Boston marriages." Originally, reports History Daily, a Boston marriage was defined as two "financially independent" women who chose to cohabitate with each other without the need of support by a man. No reference was made, however, to their sexual preferences for several more years. These days, writes ThoughtCo., the term often applies specifically to lesbian relationships. Unlike male-to-male relationships, Boston marriages continued to be somewhat acceptable during the 1800s — to the extent that Mark Twain once wrote, but chose not to publish, a story titled "How Nancy Jackson Married Kate Wilson" (per JSTOR Daily).

Apparently, a Boston marriage was just fine in the 1800s, as long as it wasn't talked about publicly. Enter Dr. Marie Equi of Oregon, whom the CCC News reports was quite open about her preference for women during the 1890s. For 10 years, Equi and her partner, Bessie Holcomb, shared a homestead along the Columbia River. One time, Equi even publicly horsewhipped Holcomb's boss when he refused to pay her. Those who knew the couple called Equi a hero. Neither she nor Holcomb were ever punished for their unconventional romance; Historic Denver maintains that unions like theirs remained legal.

Being outed could be embarrassing

As the moral majority took a stronger foothold in the West, the LGBTQ+ movement was sometimes made public in embarrassing ways. When a California pioneer woman named Hanna Allkin filed for divorce from her husband, Jeremiah, in 1856, she told the court that Jeremiah had been sleeping with other men in her own home, writes author Susan Lee Johnson in her book "Roaring Camp: The Social World of the California Gold Rush." In 1889, The Morning News in Savannah, Georgia, reported on two young ladies, Clara Dietrich and Ora Chatfield of Colorado, who exchanged love letters and eloped to Denver after they were caught. The newspaper speculated that the women were "not of sound mind."

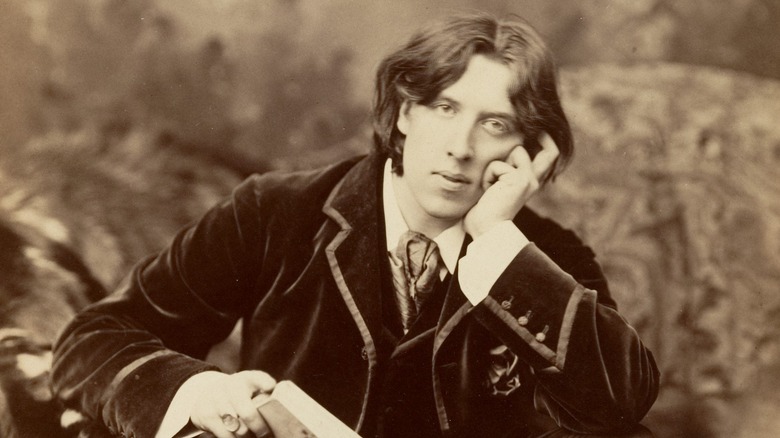

Dietrich and Chatfield may have run off together to avoid a bigger scandal or even prosecution. When poet and playwright Oscar Wilde was tried for homosexuality in 1895, History reports that his very public trial resulted in Wilde being sentenced to a London prison. Indeed, being LGBTQ+ at the turn of the century could be very tough and potentially embarrassing. In his book "A Queer History of the United States," author Michael Bronski quotes a neurologist of the time whose gay patient admitted, "The knowledge that I am so unlike others makes me very miserable" (via the Independent).

Some masqueraded as a man, or woman

In 1848, Columbus, Ohio, was among the first cities in America to outlaw appearing "in a dress not belonging to his or her sex," according to PBS. More cities would follow suit, leading to eventual edicts telling gender non-conforming folks what they could and could not wear. Although women were included, the laws appear to have focused primarily on men. In the rural West, however, men who dressed and acted as women were not singled out as much. True West writes of a Mrs. Noonan, who might have disappeared into obscurity had she not been befriended by Elizabeth Custer.

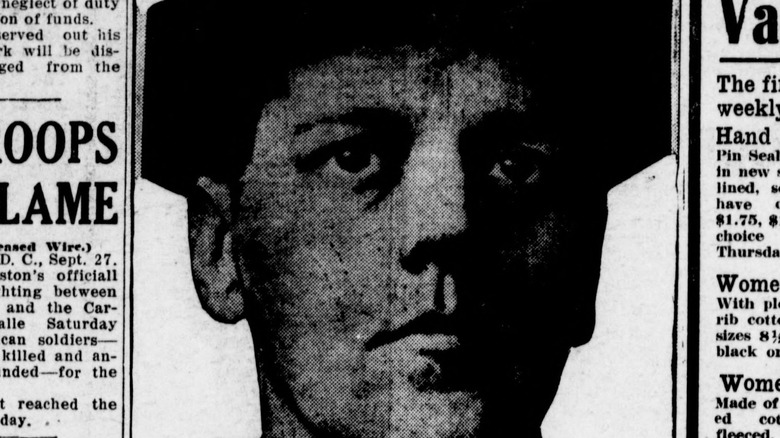

The wife of General George Armstrong Custer knew Mrs. Noonan for a few years and had nothing but good things to say about her. The "lady" was an accomplished laundress and midwife who had been married three times. She also had lost her own two children some years ago. Mrs. Custer guessed that her Mexican heritage was why Mrs. Noonan's face was "coarse" and appeared to be shaven. Only after she died did newspapers across America report that Mrs. Noonan was actually a man. Notably, she had asked to be buried immediately to save herself the embarrassment of being discovered. No such consideration was afforded Harry Allen (pictured), who was publicly exposed as a woman in men's clothing after being arrested in Portland, Oregon, in 1912 (per Peter Boag's "Re-dressing America's Frontier Past").

Others willingly outed themselves

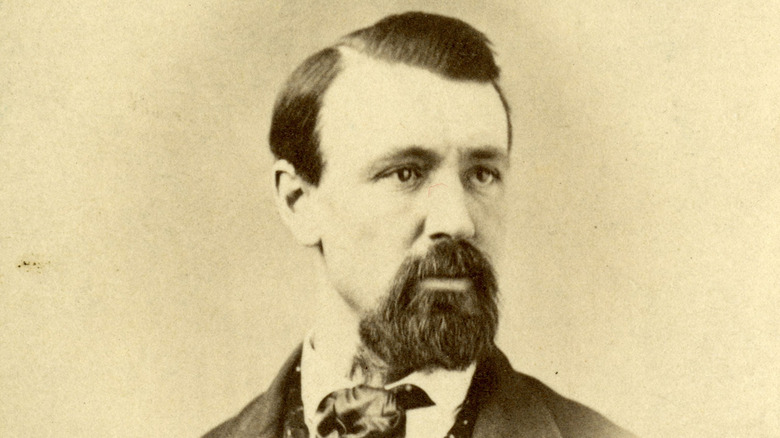

In 1884, the Albuquerque Evening Democrat reported on a somewhat tipsy woman who dared to dress in men's clothing and was seen wandering around town, declaring that her name was Captain Jack. Notably, her long hair could be seen cascading down her back. Whether or not there is more to her story is up for speculation, but it should be noted that most LGBTQ+ folks of the era did not dress as the opposite sex. Newspaper writer Alfred Doten (pictured) of Nevada, who was very much a man in manner and dress, slept with both men and women and wrote about it frequently, according to author Susan Lee Johnson.

Indeed, same-sex relationships in the West date at least as far back as the days of the American fur trade, writes the European Journal of American Studies. William Drummond Stewart, the man who hosted an all-male orgy in 1842, courted a hunter named Antoine Clement for 10 years, according to the Coeur d'Alene/Post Falls Press. But in 1843, after the orgy, the New York Daily Tribune reported that there were threats to shoot Stewart for his "rudeness" in throwing such an affair. Stewart took the hint and soon left America. He never returned.

Coming out and sexual freedoms

Today, it can be difficult to find much information on lesbianism in the 19th century. This is largely due to "lesbian erasure," writes Philadelphia Gay News, which points out how biographies of famous women often leave out their sexual orientations. A few original sources, however, do confirm that women were much more open about their same-sex relationships than men. The article on the front page of The Seattle Star that outed Harry Allen, for instance, was rather unusual — as was Allen's public comment that "I did not like to be a girl; did not feel like a girl, and never did look like a girl," via Atlas Obscura.

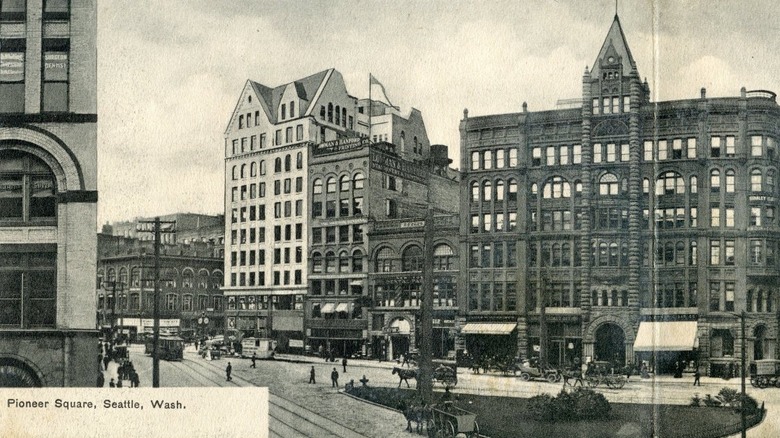

There were more: History Link talks of "Hanna Banana," a "darling old queen" who arrived in Seattle during the late 1890s. A notable drag queen, Hanna was still in Seattle as late as the 1930s. She favored hanging out at The Casino, an exclusive gay bar in Pioneer Square (pictured) where lesbians were welcome. South of Seattle, in Oregon, Alberta Lucille Hart made history as one of the first transgender men to have a hysterectomy in an early form of gender confirmation surgery. As physician Alan L. Hart, he continued working in medicine and married twice, according to Oregon Encyclopedia.

How Native peoples felt about LGBTQ+ identities

Native attitudes about LGBTQ+ identities varied, but they were mostly positive. Human Rights Campaign verifies that for generations, Native tribes acknowledged a "third gender," wherein people took on the mannerisms, dress, and roles of the opposite sex. Back in the pre-colonial era, gay Native Americans were sometimes captured during wars among the tribes and enslaved. But in the Wild West era, they were often highly regarded by their people. Depending on the tribe, they were referred to as "berdache" or "Two-Spirits." The Lakota tribes called them "Winkte," according to Wisconsin Public Radio.

Indeed, Native Americans not only accepted LGBTQ+ people for who they were, but honored and tried to assist them. The Independent writes that Nicholas Biddle of the Lewis and Clark expeditions reported that if the Mamitaree tribe noted any young boy with "girlish inclinations," he was classified as a girl and brought up as such. Another Anglo man reported that Crow tribes honored men who donned feminine dress, and that a Crow woman "who led men in battle and had four wives was a respected chief." True West writes of author Will Roscoe, who found berdache people in over 130 North American Native tribes. It was only after colonization, write Charles Callender and Lee M. Kochens in Current Anthropology, that berdache among all tribes began disappearing.

We'wha, the Zuni princess who met President Grover Cleveland

Only a handful of Native American LGBTQ+ people are remembered in history today. KQED lists five notable "Two Spirit" people in history, including We'wha, a Zuni "princess" who could speak English, made friends with Anglo settlers, and even met President Grover Cleveland in 1886. Boundary Stones describes We'wha as a "lhamana" — the Zuni word for a person who was assigned male at birth but has "female attributes" — who was a "pottery maker and cultural ambassador." According to the National Women's History Museum, We'wha was born in New Mexico, orphaned as a child, raised by an aunt, and soon recognized as a lhamana. They were taught not just domestic duties, but also "special ceremonial knowledge" and artisan crafts.

Anthropologists Matilda and James Stevenson are credited with convincing We'wha to make the trip to Washington, D.C., in 1885. According to the National Tribune, We'wha spent much time in the capital city, making many friends. During their visit with President Cleveland, We'wha asked for help from America's "Great Father" to protect Zuni lands (per author Will Roscoe's biography of We'Wha). Matilda Stevenson later wrote about We'wha, but South Dakota Public Broadcasting credits Roscoe for writing about the famous Zuni in 1991, bringing recognition and interest in LGBTQ+ Native Americans back into the public eye.