Questionable Things About Gerald Ford's Presidency

The man who would become the 38th U.S. president, Gerald R. Ford, was born on July 14, 1913, according to the Gerald R. Ford Foundation. But the name given to him at birth was not the one the world would come to know, and that marks the first of many twists and turns in this man's life. Ford was originally named Leslie Lynch King, Jr. after his biological father, whom Ford's mother, Dorothy, left mere weeks after the future POTUS was born. Two years later, she remarried a man named Gerald R. Ford. Soon, Leslie was being called Jerry Jr. and the name stuck, so much so that in his early 20s, Ford had his name legally changed.

By that time, Ford had already accomplished much. He was a preternaturally skilled athlete, having been a celebrated football player and nominated as Most Valuable Player at the University of Michigan in 1934. In fact, Ford was offered a spot on two different professional football teams, but he instead chose to enroll in law school at Yale, where he would also coach football and boxing. Ford began to practice law, served with distinction in World War II, and then briefly returned to legal work before embarking on a career in politics that would see him become one of the shortest-serving presidents of all time. His time in the Oval Office started off in a manner that, while entirely legal, was completely unprecedented.

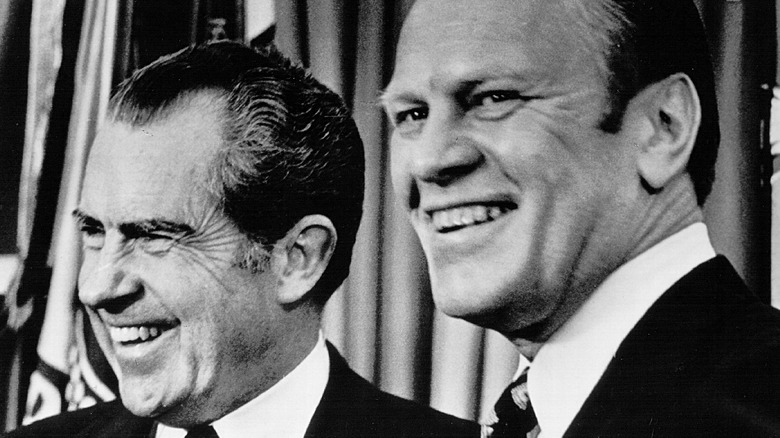

He was the only unelected POTUS or VP ever

Gerald Ford became president despite never having been elected to high office. He was never on the ticket for the presidency, nor was he ever elected vice president. Instead, he ascended to the role thanks to a series of unforeseen events and legal technicalities. Richard Nixon had been elected to a second term in office in 1972, with Spiro Agnew again serving as his vice president. But when Agnew resigned amidst a corruption scandal, Nixon nominated Ford to replace him since he was House Minority Leader and a man who had been elected to his seat an impressive 13 times. Ford easily received confirmation votes in both the House and Senate and was sworn in as the VP on December 6, 1973, per the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library and Museum.

At the time, the Watergate Scandal was beginning to embroil President Nixon. By August 1974, it was clear the president was heading for impeachment and an almost certain removal from office, so he resigned on August 9. That same day, per law, Ford assumed the role and was sworn in as POTUS despite never having been voted into high office. He knew the circumstances were wild, saying at the time (via The White House): "I assume the Presidency under extraordinary circumstances. This is an hour of history that troubles our minds and hurts our hearts."

He appointed Nelson Rockefeller as his VP despite opposition

Gerald Ford, newly appointed to office, needed to choose a vice president as soon as possible. Ford considered two men for the job — future Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and future president George H. W. Bush — but he ultimately selected someone else: Nelson A. Rockefeller, a multi-term New York governor known for a number of failed bids for the presidency and, of course, his family's wealth stemming from his oil baron grandfather. Per PBS, Rockefeller had steadily shifted further to the right side of the political spectrum over the course of the 1960s, losing many supporters. In the early 1970s, he implemented harshly punitive laws for drug crimes in New York and ordered the violent suppression of the infamous Attica Prison riots that only increased his unpopularity.

Rockefeller's confirmation hearings before Congress lasted an exhaustive four months, per Town & Country, dragged out by many traditional conservatives who opposed the wealthy governor taking the vice presidency. Rockefeller would state at one point: "This myth about the power which my family exercises needs to be brought out into the light. It just does not exist. I've got to tell you, I don't wield economic power." However, it would later come out that he had indeed used his wealth to exert power in many ways, like paying for a derogatory biography about his political rival Arthur Goldberg, per The New York Times.

Ford created a national controversy when he pardoned Nixon

Arguably the most momentous act of Gerald R. Ford's presidency was the pardoning of his predecessor, Richard M. Nixon, on September 8, 1974. Per the National Constitution Center, President Ford officially issued "Proclamation 4311," which amounted to a full and unconditional pardon of former President Nixon, legally absolving the 37th POTUS of any crimes that he had committed against the nation while serving as its leader. The Nixon pardon set off a proverbial firestorm in Washington D.C. and beyond, with countless politicians and Americans crying foul. They felt Nixon had gotten away with near-treasonous crimes for which he should have been held accountable.

But as time passed, many people came around to see the pardon as the right move to have made on behalf not only of Nixon but also of America. The nation was riven in the mid-1970s. In addition to the Vietnam War dividing the populace and the economic and social upheaval that came along with it, the Watergate Scandal and Nixon's resignation roiled political waters. None other than journalist Bob Woodward, one of the people who broke the Watergate story, would say in 2014 that the pardon was "an act of courage" on Ford's part that helped close a tumultuous chapter in American history and redirect public and political focus forward (via National Constitution Center).

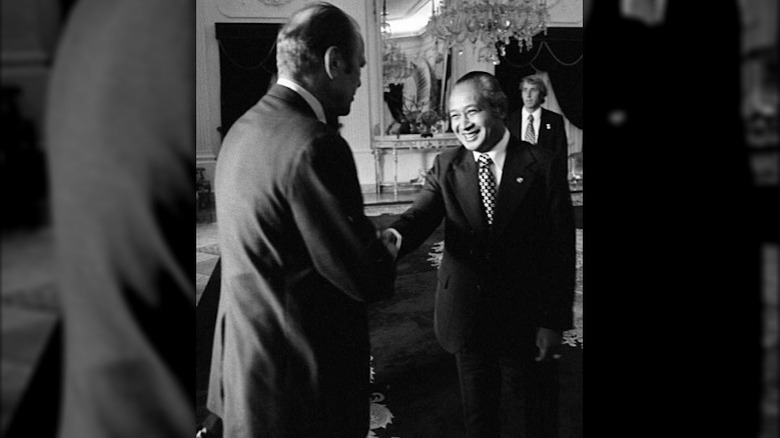

President Ford tacitly supported an Indonesian near-genocide

According to History, Indonesian armed forces invaded East Timor, a region recently abandoned by Portuguese colonizers, on December 7, 1975. The armed incursion began at the behest of Indonesian dictator Suharto and would lead to the death of upwards of 100,000 East Timorese over the next few years. Most deaths involved civilians who perished due to malnutrition in Indonesian internment camps.

As noted by scholar Noam Chomsky in a 2003 interview, the Ford administration was at least in part to blame for the suffering and death, which all but amounted to genocide. Chomsky explained that following the illegal Indonesian invasion, the Ford Administration publicly decried the operation but was in fact in support of Suharto and his forces. Though the U.S. "did join the rest of the world in formally condemning [Indonesia's operation] at the Security Council," said Chomsky, America was actually working behind the scenes to block United Nations intervention. While formally, America declared a boycott on selling Indonesian weaponry, Chomsky said the United States was in fact supplying a plethora of arms to Indonesia — something the scholar called a "major war crime."

The Ford White House abandoned Kurdish allies in 1975

America's relationship with Iraq has been a long and complicated one, especially with one of the region's marginalized groups, the Kurds. In the mid-1970s when the United States and Iran were still allies, the Shah leader of Iran asked the U.S. to offer support to Kurdish forces in Northern Iraq, according to The New York Times. At the time, the Kurds and the Iranians shared a common enemy: Iraq's de facto leader Saddam Hussein. But when Iraq and Iran settled a border dispute that had looked destined to start a war in March 1975 (the two did fight a long and costly war starting in 1980), America dropped its support of the Kurds, per The Washington Post. In doing so, it abandoned the Kurds to Hussein and his forces.

Knowing the Kurdish forces were suddenly cut off from funds and armaments, Iraqi troops attacked with greater intensity than ever before and dealt the Kurds devastation. A message transmitted to the CIA by Kurdish leadership in early spring 1975 read in part: "There is confusion and dismay among our people and forces. Our people's fate in unprecedented danger. Complete destruction hanging over our head. No explanation for all of this." This message was part of the 1976 Pike Report that the U.S. government — then led by President Gerald Ford — initially tried to keep under wraps (via The Washington Post).

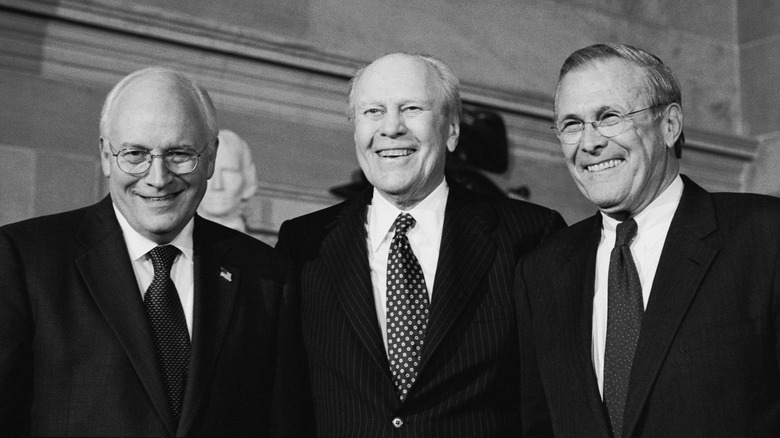

Ford attempted to veto an expansion of the Freedom of Information Act

Although Donald Rumsfeld and Dick Cheney would come to global prominence many years later during their time as part of the George W. Bush Administration, both men served critical roles during the short Gerald Ford Administration as well. Rumsfeld served as Ford's Chief of Staff while Cheney was the Deputy Chief of Staff. In a move that foreshadowed both of their later infamous political moves, Rumsfeld and Cheney convinced Ford into making one of the larger blunders of his short term in office.

That blunder, per Politico, was a veto of a bill expanding the Freedom of Information Act, frequently called the FOIA. Ford wanted to sign the bill but gave in to pressure from Rumsfeld and Cheney, who said it would be a national security risk. The move was clearly out of step with the times, for it was resoundingly rejected by Congress. In fact, in the House of Representatives, the veto was overridden by a stunning 371 to 31 vote, while in the Senate, it was rejected by a smaller but still sufficient margin of 65 votes to overturn the veto winning out against 27 votes. The expanded FOIA would pass despite Ford's veto attempt.

Ford broke a promise to keep supporting South Vietnam

America's involvement in the Vietnam War, a conflict in which the U.S. was embroiled in at least some manner for more than 15 years, led to nearly 60,000 American deaths. Many saw getting out of Vietnam as the right move, even though there was never going to be a clean way to do so.

But Gerald Ford chose a strange and unpopular way to do it, promising one thing and then doing the opposite months later. Even as North Vietnamese forces surrounded Saigon (today Ho Chi Minh City) and the ailing government of South Vietnam in April 1975, Ford resigned himself to ending American intervention in the region. But in the months preceding that fateful April, Ford had promised ongoing support for South Vietnam and had even asked Congress for more money — hundreds of millions of dollars, in fact — to continue exercising that support, per The New York Times. Then, to the shock of America's South Vietnamese allies, Ford announced an end to U.S. involvement in Vietnam during a speech at Tulane University on April 23, saying in part (via History): "Today, Americans can regain the sense of pride that existed before Vietnam." That any American pride was soon forthcoming was debatable, as was the mendacity of many of Ford's previous statements.

New York City: Drop Dead

President Gerald Ford never said the words "drop dead" regarding New York City, but in the minds of many, he might as well have. That's because the New York Daily News ran a paper with a headline reading: "Ford to New York: Drop Dead." What Ford did say in a speech in late October 1975 was: "I can tell you now that I am prepared to veto any bill that has as its purpose a federal bailout of New York City to prevent a default." Not nearly as harsh a phrasing, but it was nonetheless dire news for New York City. The metropolis, facing bankruptcy at the time and lacking sufficient means to raise the funds needed to continue proper civic functioning, had sought a financial bail-out from the federal government.

It wasn't just that Ford's reputation was tarnished by his perceived indifference to the city's plight and the stock market slump many felt was caused by his remarks. He was also criticized because his refusal to support the city was not even a stance he held to firmly. Just one month later, per President Profiles, Ford asked Congress to approve federal loans to the city.

The Air Force One tumble

On June 1, 1975, while walking down the steps of Air Force One shortly after arriving in Salzburg, Austria, President Gerald Ford slipped and fell down the last few stairs and tumbled to the ground (via New York Post). Of course, numerous cameras were rolling and the fall was captured on film and in photos and would be seen all around the world. Ford would later claim his knee had given out due to an earlier injury, and the stairs were slick with rain. But Ford's reputation as something of a clumsy klutz was established — so much so that later that same year, comedian Chevy Chase aped the president's perceived clumsiness during a sketch that opened the show Saturday Night Live in which he banged his head, misplaced a glass of water, and fell over a row of folding chairs.

Many years later, Ford's fateful fall was referenced again, this time in an episode of The Simpsons called "Two Bad Neighbors" that aired in 1996. In the animated Ford's brief time on screen, he discusses football, nachos, and beer, and then he and Homer Simpson both trip over a curb while crossing the street.

With weeks left in office, Ford suddenly called for statehood for Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico has existed in something of a state of limbo since its annexation from Spain by the United States following the Spanish-American War. Officially called the Commonwealth of Puerto Rico, it is an American territory without statehood, and thus has limited representation in the U.S. government. Its people are American citizens yet they lack many of the rights of other Americans, like voting. But one attempt to establish statehood for the commonwealth came from an unexpected source: Gerald Ford.

On December 31, 1976, just before losing his bid for reelection to Jimmy Carter and relinquishing the presidency, Ford made a completely surprising announcement that he planned to ask Congress to make Puerto Rico America's 51st state, according to the New York Daily News. Not only were members of Congress taken unawares of the sudden and strange request but so too were the people of Puerto Rico, as many then did not even want to be a state and sought full independence and sovereignty instead. The governor of Puerto Rico (and opponent of statehood), Rafael Hernandez Colon, said publicly that Ford's idea: "Does not correspond to the will of the Puerto Rican people."

Asked why he proposed such a momentous thing at that unusual time, Ford stated: "Because I'm President until January 20. It seems to me it was a very apropos time, so no one could accuse me of any ... political motives."

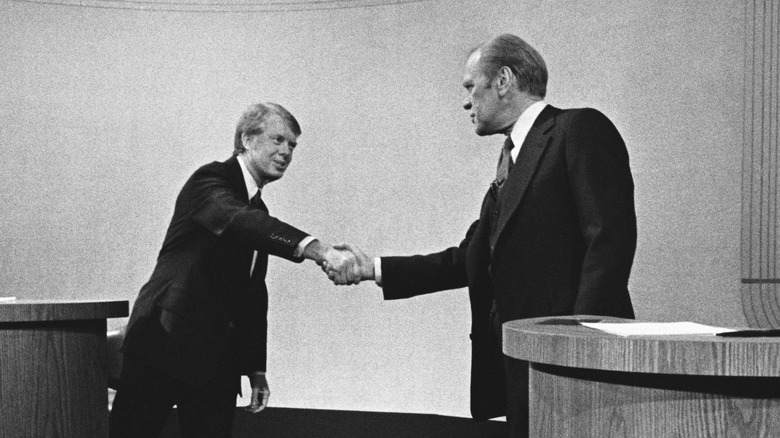

The Soviet Domination debate gaffe

During one of the several debates President Gerald Ford held with the man who challenged him and would eventually win the 1976 election, Jimmy Carter, Ford uttered a sentence that has gone down as one of the biggest gaffes in the history of presidential debates — one surpassed perhaps only by Rick Perry's "oops" many years later. Ford later explained that during the debate, he had intended to refer to the indomitable will of the people of countries living under Soviet control. He said (via The Atlantic): "There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe and there never will be under a Ford administration."

The problem? There was exactly that! The Soviet Union at that point in history was and had for decades been in control of numerous nations in Eastern Europe, and the USSR would continue to dominate these countries for another decade and a half until it finally broke up in the early 1990s. Ford attempted to walk back and explain the statement during the debate, but what lived on in the minds of viewers (and many voters) was not a president who believed in the unshakable will of a people, but a president who seemed unaware of the size and scope of America's number one global adversary at the time, the USSR. It should be noted, though, that even without this sizable gaffe, Ford would almost surely have lost to Carter anyway.

Ford had the shortest term of any president who did not die in office

With the exception of any president currently in office, whose time serving cannot be measured until his term is completed, Gerald Ford currently holds the dubious distinction of having served the shortest time as President of the United States (whose time serving was not ended by death). He served for 895 days, or roughly two and a half years, per SPU. The only presidents who served shorter times in office were Warren Harding, who died after two years and five months in office; Zachary Taylor, who died one year and four months into his first term; James Garfield, who was assassinated and died after just half a year in office; and William Henry Harrison, who famously died just 31 days after taking office.

Ford will hopefully hold the title of the shortest-serving POTUS whose time in office did not end as a result of death for a long time, for anyone who dethrones him from this title would do so only as a result of something bad, be it the death, resignation, or their forced removal from office.