The Tragic Real-Life Story Of Bloody Christmas

When asked about the LAPD's history of assaulting civilians, the Rodney King beating is often the first one that comes to mind. But over 40 years before the LAPD chased down and assaulted Rodney King, they were implicated in another vicious beating. Bloody Christmas became known as such due to the sheer violence of the beating and its bloody aftermath. And as the story of Bloody Christmas spread, it was the first time that many white people in Los Angeles were confronted with the reality of police brutality.

Although there were instances of police brutality before and after Bloody Christmas, this was the first time that there was an attempt to hold LAPD officers accountable for their behavior. In addition, the subsequent trial brought to light the lengths to which police officers would go to protect one another and established the culture of police stonewalling that continues today, known as the blue wall of silence, per the Montana Innocence Project.

Ultimately, little changed in the culture of the LAPD in the aftermath of Bloody Christmas. But this attempt to bring several police officers to justice would go down as the first criminal convictions for use of excessive force in the LAPD's history. This is the tragic real-life story of Bloody Christmas.

The LAPD and Mexican Americans

In the 20th century, the LAPD repeatedly harassed and abused Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans, as well as other non-white people living in Los Angeles, California. According to "Race, Police, and the Making of a Political Identity" by Edward J. Escobar, the LAPD started making racist associations with criminality in the 1920s and started keeping detailed statistics of arrests by race. And in "The Social History of Crime and Punishment in America," Wilbur R. Miller writes that LAPD officers believed that "violence and crime were biological characteristics" of people of Mexican descent, and as a result, frequently targeted people of Mexican descent indiscriminately. Politicians and news media were also responsible for mobilizing the bias against people of Mexican descent, according to "Latinos in a Changing Society," edited by Martha Montero-Sieburthand Edwin Meléndez.

Forecast Journal writes that among numerous civil rights violations, Mexican Americans were often subjected to random searches and unannounced raids on their homes and businesses. And in 1940, despite comprising 8% of the city population, Hispanic boys and men made up 32% of people arrested by the LAPD.

Ranging from events like the Sleepy Lagoon affair, the Zoot Suit riots during World War II, and the attempts to suppress the Chicano movement during the 1960s, The Pacific Historical Review notes that the LAPD rarely, if ever, faced any consequences for their abusive actions and operated with an air of impunity.

Christmas Eve, 1951

On December 24, 1951, LAPD officers Julius Trojanowski and Nelson Brownson arrived at the Showboat bar in response to a call about young people drinking illegally. Upon entering the bar, they approached a group of seven young men, five of whom were Mexican American and two who were white, and asked to see their IDs. According to "¡Mi Raza Primero!" by Ernesto Chávez, five of the group were also former GIs, and one was still in the U.S. Marine Corps. Daniel and Elias Rodela, Jack and William Wilson, Raymond Marquez, Manuel Hernandez, and Eddie Nora all produced identification, but despite being of legal drinking age, they were told by the officers to leave the bar. Nora later stated that he hadn't even gotten his drink when the police officers started harassing his friends, per Western Legal History.

According to The Pacific Historical Review, when all seven young men refused to leave, the officers physically assaulted them with their blackjacks and tried to pull them out of the bar. This led to a physical fight between the officers and the young men, and two officers ended up with a black eye and a cut on the forehead that required stitches, reports the Los Angeles Times.

Resisting arrest

Although no one was arrested at the time, after a few hours, the police officers showed up at the homes of the young men and arrested all of them. Six of them were taken to the station a little after two in the morning on Christmas Day and left in the waiting room after being booked. The Pacific Historical Review writes that there, they discovered that the rest of the LAPD was having a Christmas Eve party. In addition, over 100 LAPD officers were drinking alcohol that had been donated by local retailers, which was a violation of the department policy.

Meanwhile, the LAPD officers beat Daniel Rodela at his home when they arrested him and afterward at Elysian Park, where he was beaten so badly that his nose was thrown out of place and his facial bones were fractured. His kidney was also punctured due to the beating. When Rodela was finally brought to the hospital, he was so close to death that he would've died without repeated blood transfusions.

According to the Los Angeles Times, Rodela later testified that one officer said to the other after the beatings, "You'd better make your report good ... that he resisted arrest and assaulted you with a flower pot or something."

Drunken revenge for Christmas

While the LAPD officers were drinking during their Christmas Party, rumors about the fight at the bar started to trickle in. But in the retelling, the story was embellished to the point where it was claimed that one of the LAPD officers involved in the fight was going to lose his eye, the Los Angeles Times reports. In a drunken rage, the LAPD officers headed to the waiting room where the six young men were being held.

Elias Rodela, Jack and William Wilson, Marquez, Hernandez, and Nora were all ordered out of the room and forced to line up. The LAPD officers then proceeded to beat and torture all six young men for a total of 95 minutes. By the end of it, blood was everywhere. All six men suffered horrific injuries from the beating. The Pacific Historical Review writes that Nora was kneed in the groin so many times that his bladder was punctured, and for months afterward he continued to suffer due to the effects of the beating.

After the beating, they were moved to Lincoln Heights Jail, where they were beaten again. During this time, one of the officers claimed, "What's happening to these boys is life insurance for the rest of us. When I get through with these guys, they'll never jump a policeman again." Up to 50 officers participated in the beatings, while over 100 officers witnessed or had direct knowledge of the beatings.

The LAPD cover-up

The day after Bloody Christmas, as the beating became known, the Los Angeles Times published a headline that read "Officer Beaten in Bar Brawl; Seven Men Jailed." According to "America's Social Arsonist" by Gabriel Thompson, the article described a "wild barroom fight" and claimed that the young men had "ganged up" on the LAPD officers. Although there was no mention of the beatings that the young men were subjected to, the picture that accompanied the article showed them struggling to stand and appearing wounded. The paper also reported that they'd been arrested on suspicion of assault with a deadly weapon.

The Pacific Historical Review writes that for over two months, LAPD department officials hid the reality of the incident from the public. Journalists didn't question the story given by the police, which The Guardian notes is something that continues to happen repeatedly in the 21st century.

The real sequence of events on Bloody Christmas would only be revealed when the young men were tried in March 1952.

The beating of Anthony Rios

On January 27, 1952, a little over a month after Bloody Christmas, Anthony Rios and Alfred Ulloa witnessed two men beating another man as they were leaving a cafe in Boyle Heights. Upon confronting the two men, Rios and Ulloa learned that the two men were vice-squad officers F.J. Najera and G.W. Kellenberg, who were in plain clothes and were obviously drunk.

Chávez writes in "¡Mi Raza Primero!" that when additional police arrived, Rios told them that they should arrest Najera and Kellenberg as well. Instead, he and Ulloa were kidnapped by the LAPD at gunpoint and taken to the police headquarters. There, they were stripped to their underwear and severely beaten. After the beating, they were moved to Lincoln Heights jail and charged with suspicion of interfering with officers. At one point, Rios was reportedly told, "I guess this will teach you to keep your nose out of other people's business."

The trial was held on February 26, 1952, and with more and more incidents of LAPD brutality against Mexican Americans coming to light, according to The Pacific Historical Review, there was a significant amount of focus on the trial. And when the jury found Rios and Ulloa innocent, their victory was described as a vindication of all those who had been yelling from the rooftops about police brutality against minorities.

Disturbing the peace

In March 1952, the Bloody Christmas trial began against all seven young men, who were charged with battery, disorderly conduct, and disturbing the peace. The Pacific Historical Review writes that during the trial, Trojanowski and Brownson made up a story that they had peacefully asked the young men to leave the bar, but because Judge Joseph L. Call allowed testimony about the beatings, the true story of the vicious beatings was finally brought to light.

On March 12, 1952, all seven defendants were found guilty of two counts of battery and one count of disturbing the peace. However, Judge Call was so outraged by the account of Bloody Christmas that, according to "Radical L.A." by Errol Wayne Stevens, he set aside the sentences and ordered a grand jury investigation into the LAPD and indictments for those who were involved in Bloody Christmas. Calling the behavior of the LAPD "intolerable and reprehensible," Judge Call stated that the officers involved were "guilty of assault, battery, and assault with a deadly weapon -– a felony."

It was only after this moment, due to the actions of the judge, that the media started expressing interest in the case. Multiple papers devoted coverage to the story, and the Daily News ran a 10-part series that looked into the many concerning connections over the years between the police and criminals.

Widespread discussions of police brutality

After the Bloody Christmas trial, the media finally turned its attention to police brutality. And in addition to the increasing press coverage, people began protesting in city council chambers, demanding accountability from police officers. The California State Legislature even got involved, with Assemblyman Vernon Kilpatrick introducing a resolution to instruct Attorney General Brown to start an investigation into LAPD brutality. The Daily News also ran a historical segment about the LAPD that revealed that "the problems within the LAPD represented more than an aberration in official conduct, but were part of a pattern of behavior."

According to Western Legal History, this was one of the first times that a there was a wide-ranging discussion among those in the LA area about what the police were systemically doing to minorities. And The Pacific Historical Review writes that with both the Rios verdict and Judge Call's denunciation of the LAPD's actions, the charges of police brutality were legitimized in the public eye. Newspapers started printing informational pieces about what to do if someone experienced police brutality, and others even called for putting LAPD discipline under the control of the civilian police commission and the mayor. The Daily News went so far as to say that based on their actions, the LAPD was now totalitarian.

Investigations into the LAPD

Although a grand jury investigation was undertaken, many of the LAPD officers refused to cooperate and stonewalled the investigation. During their testimonies, officers either offered only vague evidence or claimed under oath that they didn't remember anything about the night of Bloody Christmas, despite having offered up names of individuals previously.

In "Radical L.A.," Stevens writes that the FBI was also asked by the Justice Department to investigate Bloody Christmas. At the time, the FBI was also investigating whether or not the LAPD had violated the civil rights of Rios and Ulloa, according to Western Legal History. Assistant U.S. Attorney Angus McEachen even subsequently compared the situation between the LAPD and Mexican Americans to Ku Klux Klan activities in the Southern United States.

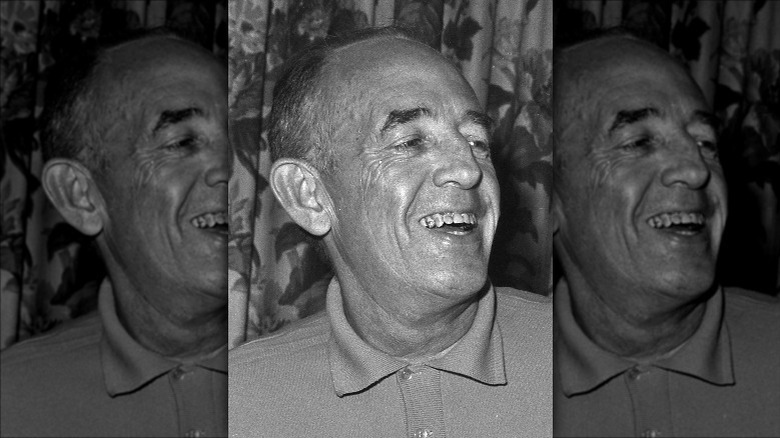

The Pacific Historical Review writes that ultimately, on April 23, 1952, only eight officers were indicted for assault after the grand jury deliberated for 11 days. In addition, Chief William H. Parker (pictured) initiated disciplinary proceedings against more than 40 officers. But although Parker publicly cooperated with the investigation, privately, he denounced it and tried to claim it was the fault of communists. The final report of the grand jury put the blame for Bloody Christmas on "a general lack of proper supervision and control" and made no mention of the LAPD's history of brutality towards Mexican Americans.

Convictions, transfers, and suspensions

Eight officers, including Lieutenant Harry Fremont, who was the officer in charge on the night of the beating, were brought to trial in separate trials between July and November 1952. The following year, Fremont was ultimately found not guilty in his felony assault trial. Out of the other seven officers, five were found guilty of assault under the color of authority. The Los Angeles Times reports that these were the first criminal convictions for use of excessive force in the LAPD's history. Robert Escobar writes in "Saps, Blackjacks, and Slungshots" that 54 officers were also transferred, and 39 were suspended without pay as a result of Bloody Christmas.

Despite Fremont's acquittal, according to Western Legal History, the evidence was so overwhelming that Judge Thomas L. Ambrose stated that the events of Bloody Christmas "indicate[d] a disgraceful state of affairs in the Los Angeles Police Department." The Pacific Historical Review also writes that of the officers who were convicted, only one person was given a prison sentence of over one year. And there was so much perjury and subornation of perjury by the LAPD that was ignored by government officials that it became clear there was a systemic institutional incentive to protect the LAPD.

Despite the convictions, "Radical L.A." notes that police brutality against non-white people in Los Angeles persisted.

The legacy of Bloody Christmas

After the trials concluded in December 1953, public attention on police brutality began to waver. The Pacific Historical Review writes that this was made especially clear by the fact that after LAPD vice officer Donald MacGregor shot and killed Servando Canales at Showboat bar, the same bar where Bloody Christmas had started, the death was described by the coroner's jury as an "excusable homicide."

Although newspapers described the LAPD as "trigger-happy" and two eyewitnesses stated that MacGregor referred to the Bloody Christmas incident before shooting Canales, the county grand jury dropped the investigation into the murder immediately after the coroner's jury declared that the shooting had been justifiable. It took only a couple weeks for it all to come to an end, and it was clearly an attempt to avoid a repeat of the problems Bloody Christmas brought down on the LAPD.

In 1990, Bloody Christmas was fictionalized in James Ellroy's novel "L.A. Confidential," writes the Los Angeles Times. But with so many other instances of police brutality by the LAPD, like the Watts Rebellion and the Rodney King beating, Bloody Christmas faded into history. And Escobar notes that in pushing back against its critics, the LAPD was able to adopt and spread its idea of police professionalism, the blue code of silence, and the thin blue line metaphor.