The Messed Up Truth About The Zoot Suit Riots

In the summer of 1943, racial tensions flared as white G.I.s attacked Mexican-Americans in downtown Los Angeles. Known as the Zoot Suit Riots due to the clothing that was popular amongst minorities at the time, the attacks sparked a period of social unrest across the United States. While social upheaval wasn't as widespread as it would later be in the 1960s, it was a stark demonstration of America's hypocrisy to be fighting racism abroad while supporting white supremacy at home.

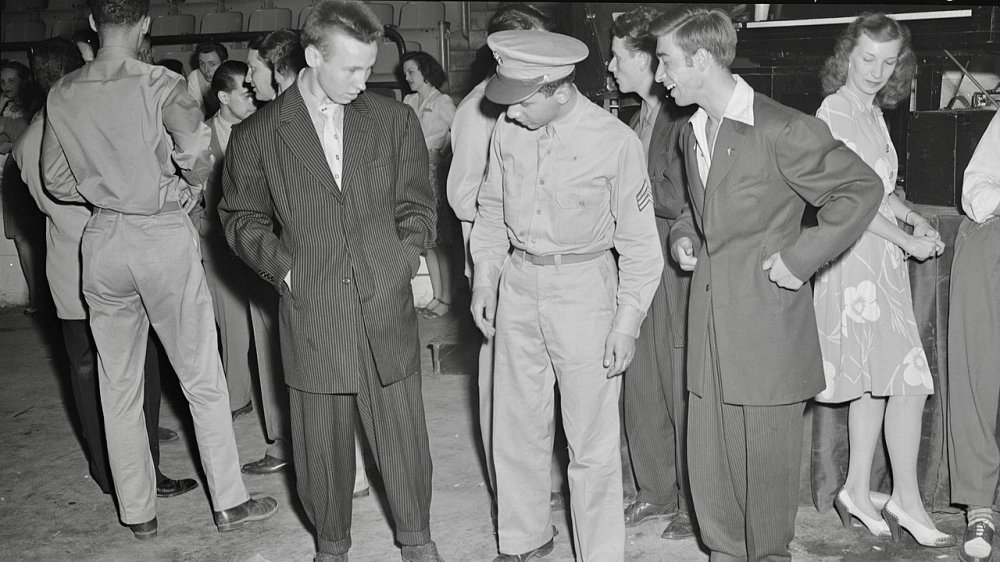

Many servicemen considered those who wore zoot suits to be subversive and unpatriotic, especially after the United States designated the zoot suits as being wasteful during the war effort. Among Mexican-American youth, wearing a zoot suit started to become a symbol of resistance and pride.

Despite the fact that servicemen initially targeted those wearing zoot suits, more than half of the people attacked and injured during the assault weren't wearing zoot suits.

Nowadays, zoot suits from that era are rare not only because of the fabric rationing, but because so many of them were destroyed during the attacks. In 2011, a zoot suit that had been originally bought for less than $20 sold at an Augusta Auction for $78,000. This is the messed up truth about the Zoot Suit Riots.

The state of Los Angeles before WWII

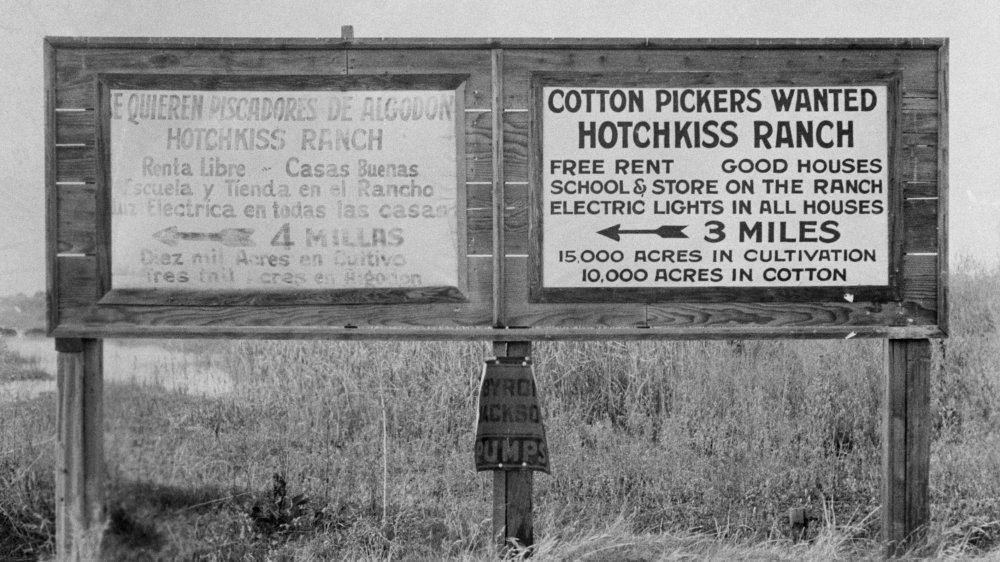

During the Great Depression, Americans across the country were struck by food shortages and the job crisis. But Mexicans and Mexican-Americans also faced the threat of deportation as the United States government sought to address the job crisis.

According to NPR, during the late 1920s and early 1930s, Attorney General William Dill started a program of deportations. Meanwhile, several United States companies also said to their Mexican workers that they were better off going back to Mexico. During this time, the LA County relief, or welfare, agencies began going out and recruiting people of Mexican ancestry to return to Mexico. They initially called it the "deportation desk," but after the LA legal counsel said that that was illegal, they started calling it repatriation.

While repatriation makes it sound like it was a voluntary procedure, it wasn't. People disappeared off the streets or agents would show up at someone's door with train tickets, informing them that they were to leave in two weeks. There were many raids across California, such as the La Placita Raid in 1931, where immigration agents sealed off the exits to La Placita park in order to capture people.

Between one million to two million people were deported during this time. And according to "The Forgotten Repatriation of Persons of Mexican Ancestry and Lessons for the War on Terror" by Kevin R. Johnson, roughly 60% of people with Mexican ancestry who were deported were United States citizens.

The murder at Sleepy Lagoon

On August 1st, 1942, there was a birthday party at a quarry pit called Sleepy Lagoon, a popular swimming hole for Mexican youths due to public pools being segregated and off-limits to Black, Asian, and Mexican people.

According to California State University, Los Angeles, the next day José Gallardo Díaz was found unconscious by Sleepy Lagoon. He died shortly afterward in the hospital. The cause of death was ruled to be blunt trauma to the head, and one medical examiner reported that his wounds indicated he had been hit by a car.

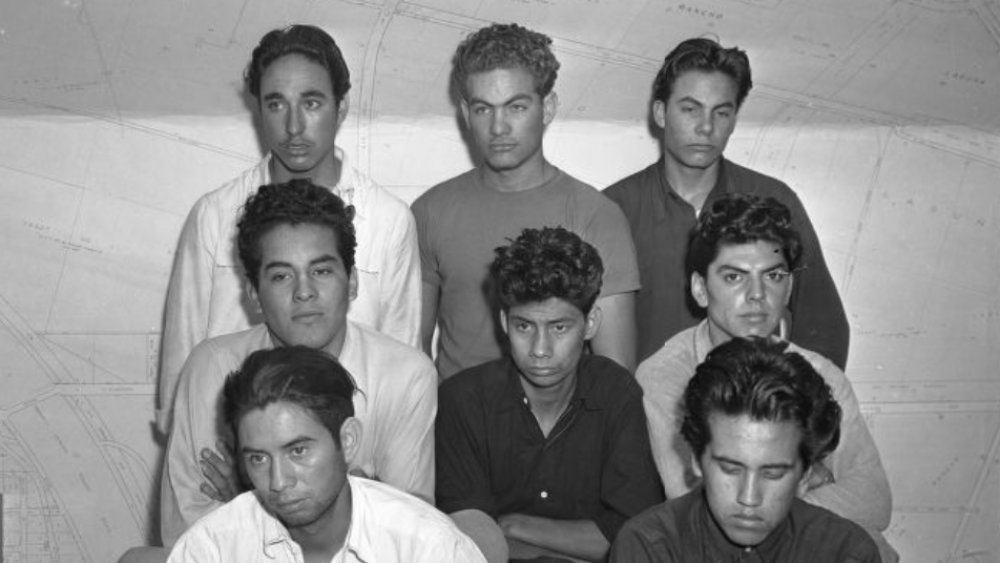

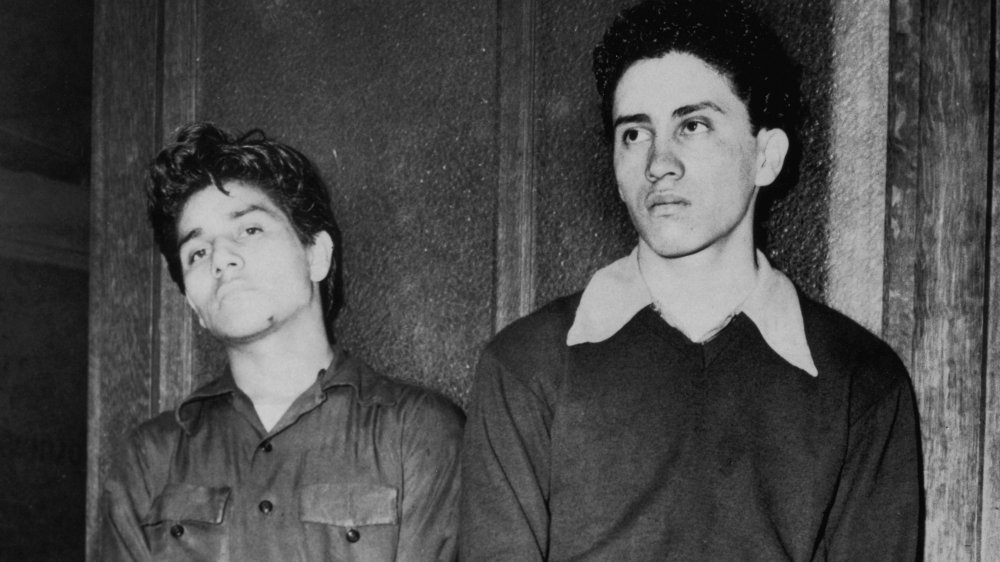

While the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) normally ignored violence amongst minorities, the state realized they could use the event to send a message to what they considered to be a threatening social movement. The LAPD arrested 600 young Mexican-Americans for the murder, considering the fact that they were wearing zoot suits to be a sign of guilt. Ultimately, 22 people were charged with murder, many of whom were minors. The trial lasted for five months, and on January 15th, 1943, the jury found 17 out of the 22 men guilty of varying degrees of murder and assault while the other five were convicted of lesser charges.

According to Oxford University Press, the 17 young men were found guilty despite the fact that there was no eye witness, weapon, motive, or a connection drawn between the accused and the crime. While the convictions were overturned in 1944, the trial perpetuated anti-Mexican sentiments.

What are zoot suits?

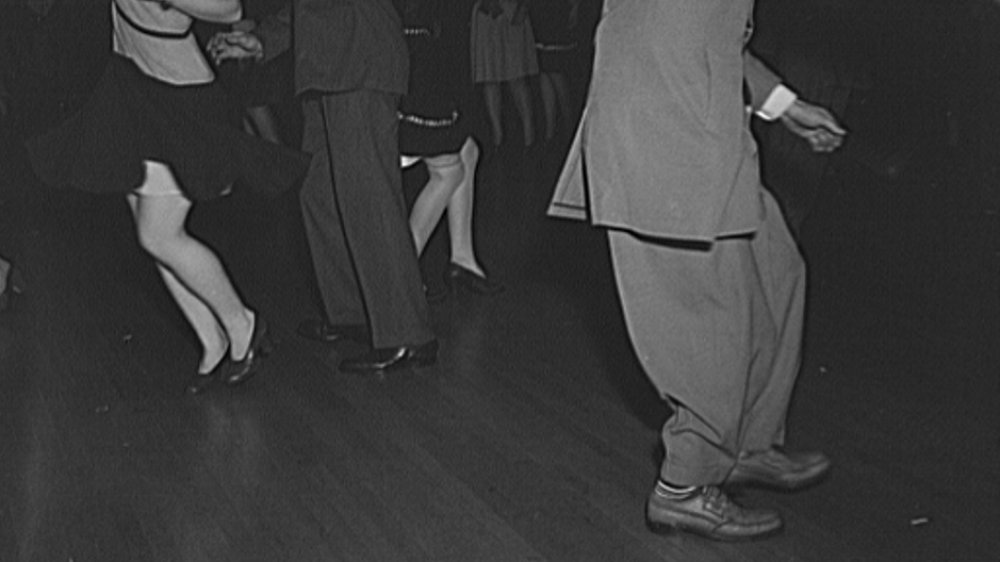

Zoot suits, also sometimes called zuit suits, were a style of suit known for their padded shoulders and high-waisted, pegged trousers. According to Smithsonian Magazine, zoot suits originated in the Harlem dance halls in the mid-1930s. The signature flowing trousers that cuffed at the ankles were done in that way in order to prevent dancing couples from tripping when they twirled.

By the 1940s, zoot suits were worn throughout the country, primarily by non-white men and working-class men. They couldn't be bought in department stores and weren't associated with a particular designer. Instead, they were fashioned by taking suits several sizes too big and tailoring them.

According to the Pomona Zoot Suit Discovery Guide, the terms "pachuco" and "pachuca" were coined to reference Mexican-American men and women who wore zoot suits or bore attire that was inspired by the zoot suit look. For many, such as Ralph Ellison, the history of the clothing was "conceal[ing] profound political meaning." Malcolm X describes his first zoot suit in his autobiography and, according to ThoughtCo, even Cesar Chavez wore zoot suits as a teenager.

The regulation of fabric and its effect on zoot suits

After getting involved in World War II, by March 1942, the United States began rationing various materials, one of which was wool. According to the Geneva Historical Society, the War Production Board wanted to cut the use of fabrics by 26% and they instilled restrictions on clothing. Suits no longer had vests, skirt hems now had to be under a certain circumference and the hems themselves couldn't be more than a certain depth. Things such as pocket flaps and belt loops were even regulated. Many people considered their compliance with government regulations as a sign of patriotism.

The rules of the War Production Board effectively made zoot suits illegal since they used extra fabric compared to other suits. According to Smithsonian Magazine, the rationing of fabric made wearing zoot suits "an inherently disobedient act."

Despite the regulation, many bootleg tailors in New York City and Los Angeles continued making zoot suits. Many white Americans considered those wearing zoot suits to be subversive since they were thought to be deliberately disregarding the rationing regulations.

The bigotry of servicemen

The combination of seeing people in zoot suits and the Sleepy Lagoon murder increased the resentment toward Mexican-Americans, especially among servicemen. According to Multicultural America: A Multimedia Encyclopedia, edited by Carlos E. Cortés, G.I.s not only found the pachuco style to be offensive and alien, but they also resented pachucos for seemingly not being involved in the war effort. The servicemen begrudged the fact that they were about to ship off to fight in a war while they saw Mexican-Americans enjoying life as civilians.

The G.I.s didn't care that Mexican-Americans were actually overrepresented in the military during World War II, with recent estimates saying that 500,000 Mexican-Americans served in the war. The G.I.s also paid no mind to the fact that those they saw in the street were underage and would've been ineligible to serve regardless. They merely saw people who weren't in uniform and considered them unpatriotic enemies.

According to the Pomona Zoot Suit Discovery Guide, in actuality Mexican-American men and women were essential to the war effort, both abroad and at home. Many Latinas joined the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps, also known as the WAC, and during the war, thirteen Latino servicemen were awarded the Medal of Honor.

The importance of pachucas

While the story of the zoot suits has typically focused on men, women were pivotal not only to the riots but towards the expansion of non-white women's liberation during World War II.

According to States of Incarceration, the pachuca's femininity challenged normative notions of sexuality, gender, and race. Pachucas were derided in the English-language press and rumors were spread claiming that pachucas hid knives in their tall hairdos. While white Americans considered the pachuco and pachuca to be subversive, pachucas were also insulted by the Spanish-language press.

Many in the Mexican-American community thought that pachucas were disrupting the ideal notions of Mexican-American womanhood. Pachucas were disparaged as being too masculine and were considered by some to be traitors to their own people, or malinches. According to KCET, pachucas were mocked and punished for not adhering to tropes regarding feminine norms, American citizenship, or an oppositional Chicano identity.

According to "Saying Nothin" by Catherine S. Ramírez, the language of the pachucas and pachucos also set them culturally apart. They spoke in a combination of Spanish, English, and pachuco slang which, instead of being seen as multilingual code-switching, were considered "an utter lack of language" by both Spanish and English speakers.

The Zoot Suit Riots started with 12 sailors

On May 31st, 1943, 12 sailors on shore leave got into a fight with local pachucos. One of them, Seaman Second Class Joe Dacy Coleman, U.S.N. was badly injured. When word got around to other servicemen, they decide to attack in retaliation.

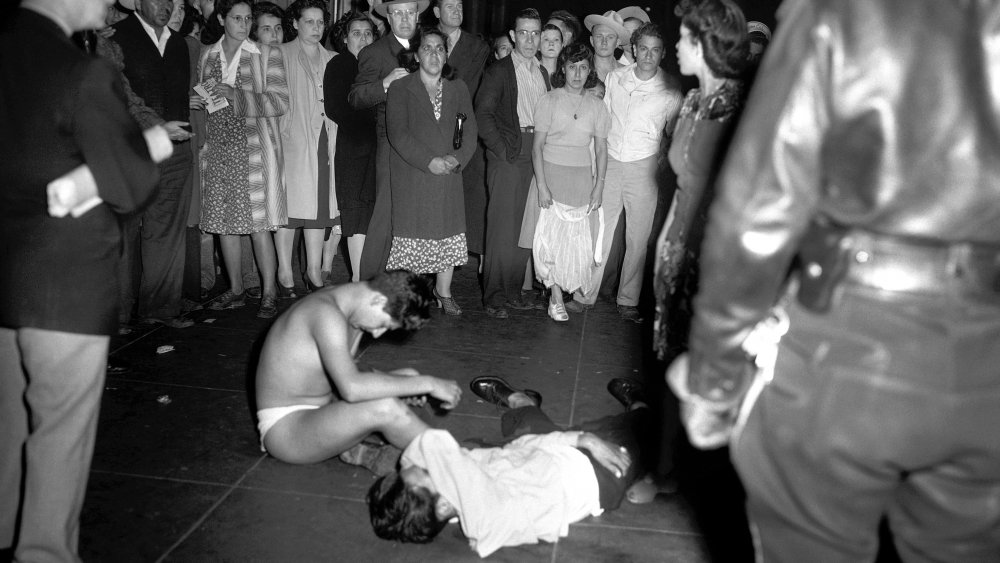

Three days later, on June 3, over 200 uniformed soldiers set out into the Mexican-American community in East Los Angeles where they had previously had confrontations with pachucos and began an assault on anyone they could see wearing a zoot suit. They brought makeshift weapons to beat people with and, per the Pomona Zoot Suit Discovery Guide, stripped and destroyed their clothing while the LAPD stood back and watched.

According to the Los Angeles Almanac, while a few sailors were arrested that night, they were quickly released and no one was ever charged. Near the end of the night, the police also swooped in to arrest the Mexican-Americans who had been the victims of the assault. As an Introduction to Latino Politics in the U.S. by Lisa Garcia Bedolla notes, one policeman stated after the riots that "the cops had a 'hands-off' policy during the riots. Well, we represented public opinion. Many of us were in the First World War, and we're not going to pick on kids in the service."

This gave the servicemen a feeling of legitimacy and felt emboldened to continue their attacks. Ultimately no one died, but over the next few days, the servicemen injured over 150 people.

The escalation of attacks

The attacks continued over the following nights. By the second day, when the sailors couldn't find enough zoot suit-wearers to satisfy their bloodlust, they took their assault into Mexican-American neighborhoods.

While the attacks initially targeted Mexican-Americans, they quickly began to include Black people and Filipino-Americans as their victims as well. The servicemen were trying to re-establish their superiority over the pachucos, and it became normal for them to ambush and strip pachucos of their clothes and leave them in the street. Servicemen dragged non-white kids out of cafes, diners, and movie theatres and into the street, some as young as 12, per PBS. They were beaten viciously.

According to "The Zoot-Suit and Style Warfare" by Stuart Cosgrove, in one such incident, two pachucos were dragged in front of an audience during a film, stripped, and had their clothes urinated on by the servicemen.

The riots lasted for five days, with the worst of it occurring on June 7th, when thousands of marines, soldiers, and sailors travel to Los Angeles from as far as San Diego to join the assault. Taxi drivers even start offering free rides to Mexican-American neighborhoods. The local press basically encouraged the attacks, suggesting that the servicemen "trim the 'Argentine Ducktail' haircut that goes with the screwy costume." The Governor's Citizen's Committee Report on Los Angeles Riots reported that only about half of the victims actually wore zoot suits.

You're grounded

The attacks didn't begin to subside until June 8, when senior military officials declared the entire downtown of Los Angeles off-limits to all marines, soldiers, and sailors. According to the Los Angeles Daily News, the servicemen were essentially grounded and weren't even allowed to leave their barracks. Although confrontations continue over the next few days, they aren't as intense or coordinated.

According to the Governor's Citizen's Committee Report on Los Angeles Riots, military officials made this decision because they realized that the LAPD was either unable or completely unwilling to deal with the situation. The Military Police and Shore Patrol had also been given orders to arrest any personnel acting disorderly.

On June 8, the Los Angeles City Council passed a resolution that made wearing a zoot suit in public illegal, punishable by up to 50 days in jail, ostensibly to address one of the causes of the riots. Councilman Norris Nelson claimed that if they could prohibit nudism and underdressing, then they could prohibit overdressing.

Lisa Garcia Bedolla reports that during these five days of assaults, over 150 Mexican-Americans, Filipino-Americans, and Black people had been injured. Meanwhile, the LAPD had arrested and charged over 500 Latino kids with vagrancy and rioting. Not a single white serviceman was charged.

In the end, the violence in Los Angeles lasted ten days, and thankfully no one was reportedly killed.

Riots spread across the country

As the initial assault in Los Angeles winded down, more assaults and civil unrest began to pop up across the country. The assaults on Mexican-Americans soon spread out of Los Angeles and California into cities in Arizona and Texas. According to Cuz: The Life and Times of Michael A. by Danielle Allen, attacks on Mexican-Americans reached Chicago, Philadelphia, and New York.

This simultaneously led to a revolt across the country as racial tensions were exacerbated. Black zoot suit-wearers had also been targets of violence, and in the summer of 1943, Black people revolted against the abuse in Harlem and Detroit. There was also an assault in Beaumont, Texas, where white workers assaulted Black neighbors, looted stores and restaurants, and ransacked the homes of Black Beaumont residents.

The fact that the United States was at war "fighting racist tyranny abroad while the majority sanction the doctrine of white supremacy and racial discrimination at home," as writer Louis Martin put it, seemed to add insult to injury.

All these events were described as race riots. While race was certainly a factor in the various upheavals and assaults, whether or not they can be described as a riot is debatable because a riot requires a "disturbance of the public peace" and none of these events were preceded by peace.

Who was to blame for the Zoot Suit Riots?

Newspapers around the country placed the blame on the zoot suit-wearers. The Los Angeles Times commended the sailors for teaching a "great moral lesson" to the zoot suiters and the Minneapolis Star reported that the victims of the attack were undeniably guilty of various crimes. Most tried to give the riots a single cause, whether it was the Mexican-American zoot suit-wearers, juvenile delinquency, or even Nazis.

Both The Los Angeles Times and the Los Angeles Examiner blamed zoot suit-wearers for the riots, though the Examiner went further, writing that zoot suit gangs had overrun the city and were hurting the city's reputation.

According to the Los Angeles Almanac, First Lady Lady Eleanor Roosevelt issued a statement saying that the riots went beyond mere zoot suits and were instead "a racial protest" that targeted Mexican-Americans. The Los Angeles Times took offense at this claim, for they had never explicitly described the zoot suit-wearers by race. They accused her of adding "nasty fuel to a propaganda fire" and, according to People's World, of having communist leanings.

An Un-American investigation

The United States was anxious not to upset its diplomatic relations with Mexico in the middle of the war effort. On June 15, Secretary of State Cordell Hull assured Mexican Ambassador Francisco Castillo Najera that the United States was intending to have a full investigation into the matter.

According to "The Zoot-Suit and Style Warfare" by Stuart Cosgrove, two investigations were started as a result of the assault on Mexican-Americans. One was designated a fact-finding investigation and was led by Attorney General Robert Kenny and Bishop Joseph T. McGucken, and the other was devoted to un-American activities, led by State Senator Jack B. Tenney. Tenney's investigation was meant to determine whether or not the riots were instigated by Nazis in an attempt to spread discontent and disunity amongst Americans.

Senator Tenney later claimed that the attacks were in fact "Axis-sponsored", although he was never able to give any evidence towards the claim. In June, Senator Tenney had already been imploring the California legislative committee to investigate the involvement of members of the Nazi Bund, the Communist Party, and fascist organizations.

Senator Tenney ultimately ignored the findings of the McGucken committee and also paid no attention to the fact that the Sleepy Lagoon convictions were overturned on October 4th, 1944, reporting instead that the National Lawyers Guild was a "communist front."