How WWI Had A Profound Effect On The Science Of Plastic Surgery

People undergo plastic surgery for a variety of reasons. Reconstructive surgery is common for those with birth defects, major injuries, and health conditions. Others, however, choose to get cosmetic surgery to enhance their appearance. Plastic surgery has been around for centuries, but the procedure was far different from how it is done today. As noted by Royal Free London, plastic surgery goes as far back as the 1400s, and the most common part of the body that was operated on was the nose.

A major advancement in plastic surgery came in the 1800s with the use of skin grafts that was developed in ancient India. The procedure was published in the late 1700s and became widespread in the Western world. It wasn't until the 20th century that developments in the field allowed surgeons to execute safer and more complicated procedures, according to Very Well Health. A variety of plastic surgery techniques were introduced after World War I and existing ones were further refined to achieve more desirable results in patients.

World War I injuries

The weapons used during World War I resulted in devastating injuries. As reported by World War I Centennial, explosives used during the war made burn injuries common among soldiers, and although not fatal most of the time, the injuries left patients disfigured and disabled. Many on the battlefront died of exploding artillery shells, and those who survived had shrapnel wounds on their faces and bodies that left them unrecognizable.

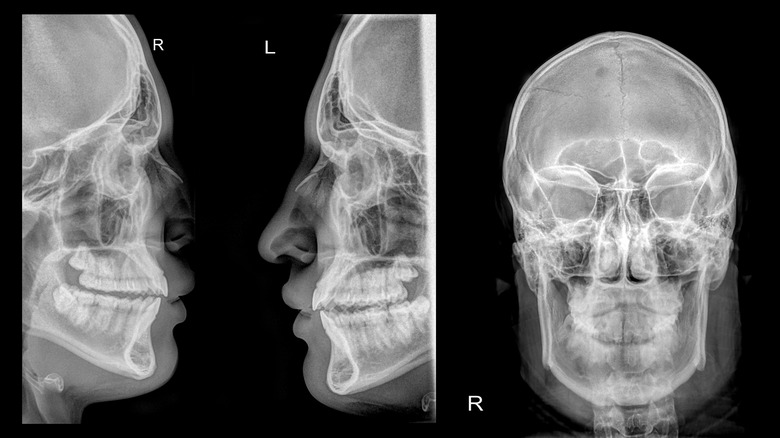

According to the National Army Museum, although surgeons did what they can to treat the wounded on the frontline, facial injuries — which were common — were quite difficult to fix. They resorted to stitching wounds, and the result after it healed left faces badly disfigured. The problem wasn't just cosmetic. Some had difficulty eating or drinking, breathing, and even seeing because of the tightness of the skin on their face. More severe cases left soldiers with gaping holes and craters on their faces where skin and flesh used to be. In total, World War I resulted in 10 million casualties and about 21 million wounded (per Yale University Library).

The Father of Modern Plastic Surgery

New Zealander Harold Gillies studied medicine in England and became a surgeon who specialized in ENT (ear, nose, and throat). He worked on the Western Front as part of the Royal Army Medical Corps during World War I (via Te Ara). The doctor witnessed firsthand how facial injuries were fixed and realized that special focus was needed to reconstruct the faces of the wounded. Moreover, those who returned home with disfigurements were cast aside by society. As medical historian and author Lindsey Fitzharris told NPR, "This was a time when losing a limb made you a hero, but losing a face made you a monster."

The demand for facial reconstruction surgery was so high that Gillies prompted medical chiefs to establish a unit solely for treating facial injuries. In 1916, the unit opened at the Cambridge Military Hospital in Aldershot. According to The Conversation, thousands of patients came through its doors. Gillies used trial and error as well as old plastic surgery techniques, but he also developed his own approach called tube pedicle skin-grafting.

Tube pedicle skin-grafting

The special unit in Aldershot was operating at full capacity, which prompted Harold Gillies to open Queen Mary's Hospital in Sidcup in 1917. Apart from having disfigured faces, the patients who entered the facility were also psychologically affected by their injuries and felt a loss of identity. According to NPR, Gillies banned mirrors in some rooms to prevent patients from seeing their injuries and worsening their trauma.

Using skin grafts has been around for some time, but one of the challenges often encountered was the rate of infection among patients. To address this issue, Gillies used separated healthy skin from a patient — careful not to detach fully detach it from the body — and attached it to a tube that was stitched to the injured part of the face (via The Conversation). The connection via the tube ensured blood flow and prevented the wound from getting infected. After some time, the tube was removed, leaving the healthy skin graft in place. The result wasn't perfect looks-wise, but it was a huge advancement in the field of facial reconstruction surgery and provided improvement to the quality of life of the patients.

The surgery of Walter Yeo

One of the first patients to be treated by Harold Gillies using the tube pedicle skin-grafting method was Walter Yeo, an officer in the Royal Navy. He was severely injured in the Battle of Jutland in 1916 aboard HMS Warspite, which left him without his upper and lower eyelids (via Alchetron). In 1917, Yeo pushed forward with the surgery wherein healthy skin from his chest was used to cover the affected areas on his face.

The surgery was done in several stages, but there were complications due to infection. However, it was successfully treated and overall, the reconstruction surgery was a success. As reported by ATI, Yeo's quality of life improved after the procedure, and he was even able to go back on active duty before being discharged in 1921. Minor reconstructions were carried out afterward for aesthetic reasons, and Yeo lived a long life. He died in 1960 at 70 years old.

The foundations of plastic surgery

The developments in reconstructive surgery during and after World War I laid the foundations of modern plastic surgery. Harold Gillies chronicled some of the cases he worked on in a book titled "Plastic Surgery of the Face" which was published in 1920. As reported by The Conversation, by the time the war ended, 11,752 operations had been done at Queen Mary's Hospital. As Lindsey Fitzharris said, Gillies did not only restore the faces of his patients for medical reasons but for aesthetics as well, which aided in society's acceptance of them.

The impact of World War I made surgeons explore more complex procedures, and they had a better understanding of how to prevent infections, and develop better anesthetics. In addition, the concept of cosmetic surgery became more widespread afterward as a result of the work done on the faces of wounded soldiers. According to the National Army Museum, many of the techniques that were developed and refined during the war are still used in reconstructive surgeries today.