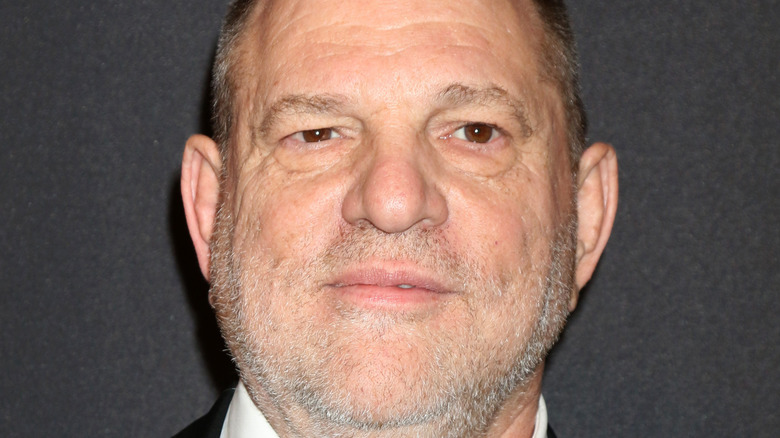

Just How Much Work Went Into Breaking The Harvey Weinstein Scandal?

In 2017, a New York Times article written by journalists Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey detailed sexual assault and harassment allegations against Hollywood mogul Harvey Weinstein. Accusations included in the report were brought by actresses Rose McGowan and Ashley Judd, among others, as BBC News explains. The piece not only helped bring down the high-powered movie executive, but it also rewrote the rules of Hollywood. In the aftermath of Kantor and Twohey's investigation, further sexual misconduct allegations were brought against Weinstein as well as a number of other powerful men in film, TV, and media — all part of what's now called the #MeToo movement.

The 2022 film "She Said," starring Carey Mulligan and Zoe Kazan as Kantor and Twohey (with a trailer on YouTube), tells the story of how that 2017 New York Times article was researched and written, the work required from Kantor and Twohey to get Weinstein's accusers to come forward, and how risky it was for all those involved to help bring Weinstein to justice (via IMDb). The 2022 film is based on Kantor and Twohey's bestselling 2019 book "She Said: Breaking the Sexual Harassment Story That Helped Ignite a Movement," and as the two journalists told The New York Times in 2019, from the outset, they barely knew one another, and early on, some women reportedly abused by Weinstein were reluctant to share their story.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).

The Hollywood producer painstakingly covered his tracks

As Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey's investigation revealed, accusations of sexual misconduct from Harvey Weinstein were nothing new. There was, in fact, some three decades of evidence detailing complaints brought against the film producer from actresses, colleagues, and Weinstein's employees. Those complaints came from within the Weinstein Company and Miramax, the movie production company founded by Weinstein and his brother, Bob (pictured), based on The New York Times' reporting. Signs of a pattern Weinstein of misconduct took the form of first-hand accounts from former Weinstein employees and actresses in the film industry.

Kantor and Twohey also discovered a long trail of documentation detailing assault and harassment allegations against Weinstein. Those were in the form of emails, public legal records, and files and memos from within Weinstein's company, all of which Kantor and Twohey scoured to support the allegations brought against the executive. As Kantor and Twohey told The New York Times in 2019, much of that work was done in secret. As The Guardian notes, Weinstein left Miramax in 2005 to start the Weinstein Company. The board of the Weinstein Company fired Weinstein shortly after the 2017 New York Times article was released.

Weinstein paid many women to keep quiet

As Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey's research also brought to light, allegations against Harvey Weinstein were suppressed by at least eight pay-outs and settlements with women, the earliest of which dated to 1990, and similar agreements continued all throughout Weinstein's career, according to their 2017 New York Times report. Some women who confronted Weinstein about his behavior also signed non-disclosure agreements, such as Zelda Perkins, with whom Weinstein settled secretly, based on 2017 reporting from The New Yorker. Weinstein also settled with actress Rose McGowan (pictured) in the late 1990s.

Those non-disclosure agreements and settlements between Weinstein and some of his accusers were an additional obstacle for Twohey and Kantor when they approached current and former employees and colleagues of Weinstein, asking them to contribute to their piece. As Twohey and Kantor told The New York Times in 2019, shortly before the Weinstein story broke, only one Weinstein accuser had gone on the record. To encourage more women to come forward, the two journalists told them (via The New York Times) "We can't change what's happened to you, but if you work with us and we work to tell the truth, we may be able to prevent other people from getting hurt."

One Weinstein accuser went to the New York police

Not all the evidence of Harvey Weinstein's misconduct came from within his companies, in the form of difficult-to-obtain non-disclosure agreements, or in the details of private settlements. As the 2017 New York Times report goes on to explain, one model and aspiring actress, Ambra Battilana Gutierrez (pictured), who alleged Weinstein harassed her, went to the New York police after that incident took place. For that reason, Gutierrez's story was public record, and the details of her account were easily accessible to reporters like Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, as well as others, some of whom worked for tabloids.

The public nature of Gutierrez's account shone a much brighter light on her accusations. Despite that attention, the New York district attorney's office declined to press charges against Weinstein at that time, and Weinstein also reportedly settled with Gutierrez out of court. Around that same time, concern about the highly-publicized nature of Weinstein's behavior came from within Weinstein's company, Miramax, where he was still employed. To help curb Weinstein's behavior, Miramax issued a memo — obtained by Kantor and Twohey — outlining an internal code of conduct regarding sexual harassment and related behaviors.

Internal emails revealed how much some close to Weinstein knew and when they knew it

Perhaps the most damning bit of evidence uncovered by Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey, though, was an internal Weinstein Company memo from a former Weinstein employee, Lauren O'Connor (pictured), as the Los Angeles Times reports. After learning of a specific instance of Harvey Weinstein's behavior, O'Connor wrote a memo to the board of Weinstein's company detailing the full scope of what the film producer had allegedly done and the sheer number of allegations against him. With that memo leaked to the press, a flurry of concern from within Weinstein's company erupted — including from Weinstein's brother, Bob, once he was notified of its contents.

Several from within Weinstein's company familiar with the O'Connor memo spoke with Twohey and Kantor for their story on a condition of anonymity, according to the 2017 New York Times Weinstein report. Speaking to the Los Angeles Times in 2020, O'Connor, an assault survivor, explained why in 2015, she spoke out against her former boss. At that time, O'Connor said she "had an opportunity to try and do something that could help that from not happening to somebody else." She continued: "I know what it's like, and if there is a way in which I can lessen the risk that someone is able to do that to somebody else — I had to. It was just an imperative."

Twohey and Kantor were stronger together

As can be seen, a significant amount of hard work and research went into the 2017 New York Times report detailing a pattern of misconduct on Harvey Weinstein's part, as well as the steps Weinstein and those close to the situation took to cover it up. The story also depended on the bravery of those who experienced harassment and abuse from the film executive and decided to speak out. Of that period in their career, Jodi Kantor and Megan Twohey (pictured) told The New York Times in 2019, "In some ways, our partnership echoes a theme of our work: Women can have far more impact together than separately."

Continued Twohey and Kantor, "We are both very driven, and our journalistic values match. But we have slightly different skills and views of human nature. We just try to correct and complement each other. In our book, we're inviting readers into our partnership. We want you to see what we saw, to puzzle over the same clues we did." In 2020, Weinstein was convicted in New York of rape and assault and sentenced to 23 years in prison. His legal team appealed the conviction, but the sentencing was upheld. In 2022, jury selection began for another Weinstein trial in California on additional rape and assault charges, according to BBC News.

If you or anyone you know has been a victim of sexual assault, help is available. Visit the Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network website or contact RAINN's National Helpline at 1-800-656-HOPE (4673).