The Twisted History Of The Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was one of the most formative eras for European — and thus, at least at the time, global — advancement. Sneaking into the timeline right in the thick of a mess of other revolutions — the Renaissance, the Reformation, the French Revolution, the War of the Roses, and more — it was certainly a good fit for the aesthetic of the time. And thankfully, unlike many of those other revolutions, this one was less bloody — well, somewhat.

Up until the kickoff of the Scientific Revolution in 1543, per Britannica, so much of modern science and medicine was based on the writings of the Greek physician Galen — who died in 216 AD (via Britannica). That means for well over a millennium, the world's understanding of the human body and the universe we lived in was held in stasis. The Earth was the center of the universe, the body revolved around the four humors, blood came from the liver, the heart was just behind the sternum and split into two parts — the list goes on, and it was pretty much all wrong. And that was just the medical and anatomical side of things.

Needless to say, the scientific world needed one heck of a revolution. One that would bring new energy to 1,300-year-old teachings. One that would figure out where we fit in the universe and maybe, just maybe, loosen up the iron grip that the Catholic Church had on practically everything in Europe and further abroad. That doesn't mean it was all roses, though: There were a lot of murky details mashed in between the advancements. Here's a look at the twisted history of the Scientific Revolution.

A dissected felon helped us all

When Jacob Karrer von Geweiler married his second wife while he was already married to his first — committing a crime of bigamy — and then attempted to murder one of those angry wives with a knife, he probably didn't know what his legacy would look like. And it really shouldn't have looked like much: He was beheaded for his crimes on May 12, 1543, according to HistoryofInformation.com. At the time, Andreas Vesalius, a Swiss anatomist, was hard at work figuring out how the human body actually worked, and what he really needed to help him was a human body for him to dissect and study.

Conveniently for Vesalius, the body of von Geweiler found its way to him as an honor from the town of Basel, according to Anatomy Atlases, and with that body, Vesalius made the first ever public anatomy demonstration. He cut open the body of the beheaded felon to showcase how the human body was put together, before boiling the cartilage from the bone and preparing the bones for viewing. It's a display that is still visitable to this day.

At the Anatomical Museum of the University of Basel, this skeleton, prepared by Vesalius, is still on display today nearly 500 years later. And it still looks just as good as it did before.

The Church was basically a firing squad

The thing about science — and figuring out the workings of the world via empirical evidence — is that it has the potential to upset the powers that be. And at the time of the Scientific Revolution, the prevailing authority in Europe was the Catholic Church, which until then had enjoyed a nice run of unchallenged power. Everything they said was law, everything they ruled was God's will, and they claimed they were the only ones who could hear from God. Indeed, the Reformation wasn't far away for the same reasons, per Britannica.

The church was also not a big fan of science, particularly when it contradicted Christian doctrine. Take, for instance, the very unfortunate Giordano Bruno. Among the highlights of Bruno's ideas, according to Discover, was the philosophical belief that the universe was endless, and that there were other solar systems out there other than our own.

However, Bruno first had a brush with the law when he outlined every mistake a professor made in a lecture. This was considered slander, which was an offense that landed Bruno in prison. This was just the first in a string of outspoken beliefs that ended with him being bound, gagged, stripped naked, and burned at the stake. For what it's worth, in 2000, the Catholic Church admitted that it "regretted" burning Bruno at the stake, according to The New York Times.

The female reproductive system caused a bitter, and perhaps deadly, fight

There were a lot of multifaceted intellects at work in the Scientific Revolution, but these minds had specialties too. For Regnier de Graaf, the Dutch physician, that specialty was the reproductive system — particularly the female system, but he dabbled in testicles as well. He studied medicine in school, according to Encyclopedia.com, and used that training to pioneer our understanding of the reproductive organs — but it wasn't just wholesale advancement and camaraderie in de Graaf's field of study. There was an awful lot of not-so-healthy competition too, and in de Graaf's case, that rival came in the form of someone he went to school with — Jan Swammerdam.

According to the SciHi blog, when de Graaf published "De Mulierum Organis Generatione Inservientibu" in 1672, his former schoolmate Swammerdam was outraged that de Graaf had the audacity to share his recent discoveries about the ovary and its eggs, and how important these aspects of the female reproductive system are. Swammerdam believed he and his cohort Johannes van Horne had made that discovery first.

The spat got pretty heated, and not long after, at just 32 years old, de Graaf passed away. Between this conflict and the death of his son, the hypothesis is that the distress this caused him was too much to bear, and had a significant role in his untimely death.

Microbiology began as an accident

Microbiology is kind of a big deal: The Microbiology Society states on its website that "Microorganisms matter because they affect every aspect of our lives — they are in us, on us, and around us." Microbes essentially impact every single thing that happens on this earth at every moment: They're everywhere, always, and few things are more significant to the world's living inhabitants than them, despite how tiny microbes are.

So it might come as a surprise to learn that the entire study of microbiology began as an accident. It began, as no scientific breakthrough ever likely did, with a fabric seller — Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek. As described by Wired, Van Leeuwenhoek was using the most powerful microscope of his time to observe local algae because of how green and shimmering it was, when he saw a tiny creature bolt across the lens of the scope. According to our friendly Dutch fabric merchant, he figured this creature to be 10,000 times smaller than a mite.

He then began using this microscope on practically everything he could find, including his own skin and mouth, and he made a discovery that we now take for granted — microbes are everywhere. They are the second most common organisms on earth, according to Wired, and their influence goes far and wide. And while he would not live to see the impact his discovery had, it led to probably the most important breakthrough in the history of medicine: Germ theory, which postulates that some illnesses are caused by the unwelcome presence of microbes, per Britannica.

A little urine goes a long way, and sometimes too far

In 1669, in Hamburg, Germany, a merchant by the name of Hennig Brandt decided to set up a little experiment for himself. He took some urine — maybe his own, maybe not — fermented it, and, after distilling the boiled reduction, came out the other end with a pretty remarkable substance. This was what we know today as phosphorous, according to the Royal Society of Chemistry, and it has two rather impressive properties. Firstly, it can spontaneously combust in the air. Secondly, it glows in the dark. That's some premium entertainment for the 17th century.

Soon after its discovery, attempts were made to find some kind of medicinal use for it. Clearly, something that glowed and spontaneously combusted must be quite powerful, it seems to have been thought. Well, they weren't wrong, that's for sure. Brandt continued testing on it, but he also began to sell his isolated creation to other chemists, according to UNESCO, including Isaac Newton, who also created a recipe for the creation of this same isolated variant of phosphorous — which included one barrel of urine.

Phosphorous's use continued to evolve and transform over the years, its glowing residue still a fascination to chemists. And then, in 1943, it was Brandt's beloved phosphorous that would come raining back down on his city of Hamburg. Living up to its prophecized power for all the wrong reasons, phosphorous bombs burned the entire city, per UNESCO,

Isaac Newton was up to more than watching apples fall

Isaac Newton is one of those names that most people know in one way or another. He's the guy who saw the apple fall and came up with the idea of gravity, supposedly at least, per National Geographic. Whether or not the legend of the apple is true, Newton was a leading mind during the latter stages of the Scientific Revolution. As Wired relates, he was one of those rare minds that was revered even in his time for being so ahead of the game, up there with Einstein and Darwin as some of the most important thinkers of all time.

Great minds have to push boundaries, of course, but one boundary that Newton pushed only came to light recently. As it happens, when he died, he left behind so many papers and manuscripts that the word count is estimated at around 10 million. Stuck in the midst of these papers is proof that Newton also may have dabbled in some stuff the church wouldn't have liked — the occult.

Indeed, he was a heretic, by the standards of the day, and may have faced punishment had the church caught wind of it. For instance, he completely rejected the idea of the Holy Trinity, according to Smithsonian, and saw Jesus as a sort of middleman who helped connect humanity with God.

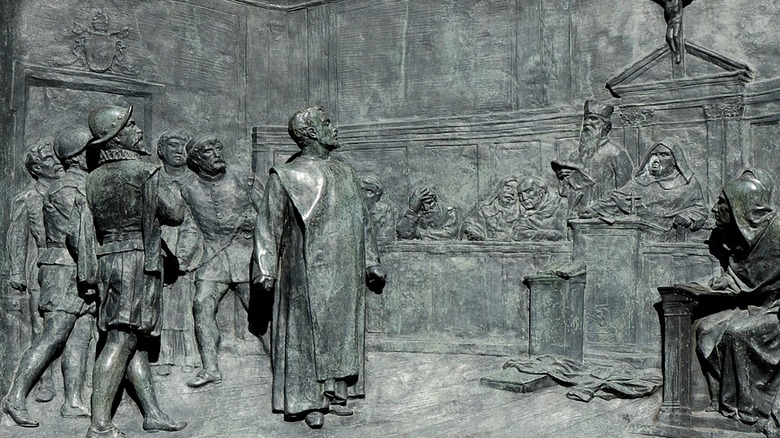

Galileo spent much of his life under house arrest

Galileo Galilei was a man whose name and reputation are pretty well established both in our day and in his own. However, according to History, Galileo backed what was at the time a very controversial idea — that the Earth revolved around the sun.

This idea had previously been proposed by several astronomers, most notably Nicholas Copernicus in 1543, and Galileo twice spoke up to essentially denounce the church's belief that it was the opposite — they said that scripture explicitly states that the Earth is the center of the universe, and to say anything otherwise was quite literally heresy.

This was unfortunate for Galileo, who soon found himself the subject of interest of chief inquisitor Father Vincenzo Maculani da Firenzuola. At his trial, which was somewhat stacked against him, the church ruled that Galileo was guilty of heresy, and condemned him to prison, quote, "at their pleasure." And with torture as the other option, Galileo agreed not to share his crazy heretical belief in the sun being the center of the solar system, and spent the rest of his life under house arrest. In case you're wondering, the church did eventually admit that Galileo was right and cleared him of the charge — in 1992, according to New Scientist.

Homunculi were on the menu

Perhaps the word 'homunculus' doesn't carry many negative connotations for people not familiar with the anime series Full Metal Alchemist, but the literal word in Latin means "little man," and includes definitions such as "an artificially made dwarf, supposedly produced in a flask by an alchemist," according to Dictionary.com – which is kind of a terrifying thought on its own.

The prospect of creating artificial life has always held hands with scientific advancement, even to this day. So it shouldn't be that surprising that back in the Scientific Revolution, when practically everything was becoming more and more possible, the creation of an artificial human being was at the forefront of some pretty great minds. While the concept of artificial life can trace itself back centuries before the onset of the Scientific Revolution, according to Ancient Origins, the experiments to get there really ramped up in the new hotbed of scientific progress.

It was the Swiss mastermind Paracelsus — famous for bringing chemistry and medicine into the same wheelhouse, among other things, per Britannica — who developed an actual recipe for the creation of said homunculus, and be warned, it's not pleasant. According to him, the semen of a man would putrefy within a horse for forty days, and then a little man would be ready. Ready for what, you may ask? According to Paracelsus, to be educated with care, not to be used for magic, though it's possible Paracelsus was writing all of this symbolically, as described by Ancient Origins.

Sir Francis Bacon's utopia was not so scientific

There are a lot of big names associated with the Scientific Revolution, such as Galileo Galilei, Isaac Newton, and Nicholas Copernicus. Among these, Sir Francis Bacon is also right up there with the greatest minds of his time. He was a philosopher — as well as a scientist — of various practices, per Britannica, but one thing he is also known for is his idea of New Atlantis, a utopian society that, in his view, was the perfect outcome for the new, scientifically-guided world.

According to "Science and Rule in Bacon's Utopia: An Introduction to the Reading of the New Atlantis," by J. Weinberger (via The American Political Science Review), Bacon's utopia was built on the premise of science being at the forefront of society, rather than politics. Which maybe doesn't sound all that bad. But that's about where the ideas end, because, as Weinberger points out, Bacon himself admits that his ideas are incomplete. He has a lot of notions, but not a lot of planning.

There's also the matter of his scientific, utopian vision being so confined by the concerns of the metaphysical. In an era where so many great minds were challenging the church — and sometimes being killed for it — Bacon's idea of advancement was hampered by how much spirituality was woven into the fabric of this utopia, according to Weinberger.

Math throwdowns were real things

The Scientific Revolution was something of a race of competing ideas. Just as is often the case today, scientists were eager to get their discoveries out there before the next person, and definitely before that next person in the next country — national pride and personal legacy were often at stake. So it was not all that uncommon to see rivals develop, with two or more great minds after the same prestige — and sometimes those minds were of competing nations.

Look at Francois Viète, for instance. He was a mathematician and attorney from Paris, who was quite popular among the French nobility. He had a close relationship with various members of the elites of France and served as an advisor to more than a few, according to the SciHi Blog. If there was such a thing at the time, you might even think of him as France's national math champion, the one they called on when mathematical dignity was at stake.

And it was most certainly at stake when Adriaan van Roomen, a Dutch mathematician of some renown, posed a mathematical problem that had yet to have a solution. He challenged mathematicians the world over (well, Europe over), according to the University of St Andrews, Scotland, and the Dutch ambassador himself slammed France, saying that there was not a mathematician in their whole nation. Rising to the occasion, it was Viète – very much a French mathematician — who solved the equation first. Van Roomen was so impressed that he even took himself a vacation to Paris, to spend more time with Viète.