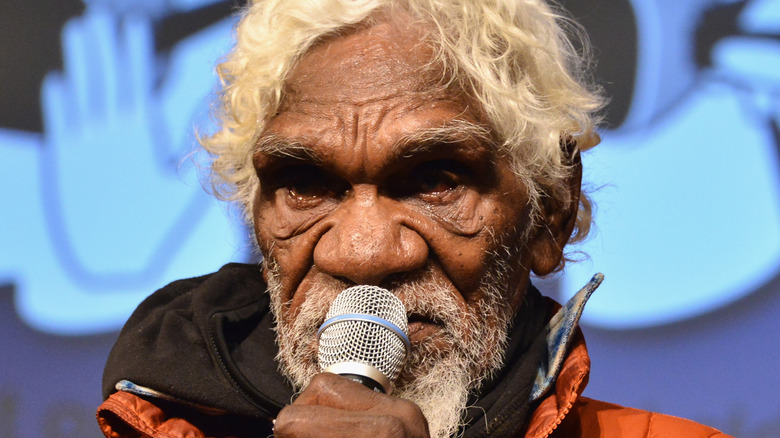

Meet Nyarri Nyarri Morgan, Who Discovered Civilization Through An Atomic Bomb

Imagine if an alien civilization found its way to Earth and began flying its vessels through our night skies or testing its weapons over our deserts. This would be a civilization that had managed interstellar travel. Would the technology they relied on be recognizable to us as technology? Would we even understand what we were seeing? If the accounts of indigenous people coming into contact with colonizing civilizations for the first time are anything to go by, encountering a new people through their technology can be an extremely disconcerting experience. For example, when members of the Squamish tribe first saw Captain George Vancouver moor his ship off Bainbridge Island in Washington state in 1792, they thought an island had come loose and was floating away, according to "Rights Remembered: A Salish Grandmother Speaks on American Indian History and the Future."

That was simply the shock of witnessing a jump from wooden canoes to large wooden sailboats. An Indigenous man in Australia had an even more dramatic experience. Nyarri Nyarri Morgan first became aware that he shared the country with settler society when he witnessed the testing of an atomic bomb during the second half of the 1950s. "We thought it was the spirit of our gods rising up to speak with us," he recalled (via ABC News).

First encounters

Nyarri Nyarri Morgan grew up in the desert of Western Australia as a member of one of the world's oldest living cultures — the Martu tribe (via LynetteWallworth.com). The Martu are the original inhabitants of what is now considered central Western Australia (per KJ). According to SBS, the oldest archaeological site in their territory dates back more than 50,000 years. They were also one of the last indigenous Australian groups to make contact with its European inhabitants, a process that didn't really begin until the 1950s and 1960s (via KJ). During the early part of Morgan's life, therefore, he had no idea that he shared Australia with an entirely different civilization. But that all changed dramatically one day in the 1950s, according to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

During that decade, the Australian government gave the British permission to test nuclear weapons within its borders, according to National Museum Australia. Between 1952 and 1963, the UK tested 12 different nuclear bombs at three Australian locations: the Montebello Islands off Western Australia and Emu Field and Maralinga in South Australia. It also conducted around 200 minor trials. The majority of the tests occurred at Maralinga, with the first taking place on September 27, 1956. It was one of these tests that transformed Morgan's perception of reality when he was a young man walking with his two younger brothers in the northern part of South Australia (via LynetteWallworth.com).

Fallout

At first, Nyarri Nyarri Morgan and his community thought the explosion was a positive sign. "[W]e saw the spirit had made all the kangaroos fall down on the ground as a gift to us of easy hunting so we took those kangaroos and we ate them," he remembered (via the Australian Broadcasting Corporation). Feasting on the nuked kangaroo meat turned out to be a mistake, however, as everyone who ate it got sick. They weren't the only ones who suffered from the fallout of something they couldn't understand. "We all poisoned, in the heart, in the blood and other people that were much closer they didn't live very long, they died, a whole lot of them," Morgan said. The testing also spread white powder that killed kangaroos and spinifex grass and lit drinking water on fire. Morgan said he and others breathed in smoke from the explosion through their noses. When he drank the water after the flames were extinguished, it was still hot.

Morgan wasn't the only indigenous Australian impacted by the tests. Indigenous communities near Emu Field described a "black mist" settling over their homes after detonations (via The Conversation). "It wasn't long after that a black smoke came through. A strange black smoke, it was shiny and oily. A few hours later we all got crook, every one of us," Yankunytjatjara elder Yami Lester recalled, adding that everyone experienced nausea, diarrhea, and skin rashes. His eyes were so sore he couldn't open them for weeks, and elders died.

'They got it wrong'

All told, the British government detonated seven bombs at the Maralinga site, according to BBC News. Combined, they had double the force of the bomb the U.S. dropped on Hiroshima, Japan. At the time, the British government chose to test their weapons in the Australian outback because it was larger and, they believed, more remote than anywhere on British soil. "They thought they'd pick a supposedly uninhabited spot out in the Australian desert," the site's caretaker Robin Matthews said (per BBC News). "Only they got it wrong. There were people here." While perhaps no one had less context for the tests than Nyarri Nyarri Morgan, the Anangu Pitjantjatjara community near Maralinga was not given much more warning, according to National Museum Australia. A single patrol officer was assigned to drive across hundreds of thousands of square miles to find and warn people.

There were also not many precautions for the workers at the test sites. Footage from the time shows soldiers watching the blasts in shorts and T-shirts with nothing to protect their eyes but their hands. The two governments exposed more than 16,000 workers to radiation, according to The Conversation, and they were 23 percent more likely to get cancer and 18 percent more likely to die from it than the general population. Indigenous communities near the test sites still have higher rates of cancer and cancer deaths than Australians on average, according to National Museum Australia.

Compensation and remediation

The extent of contamination at the Maralinga site was not fully known until 1984, when Australian scientists were testing it in order to return it to its original Tjarutja owners, according to National Museum Australia. Then, they discovered that it was heavily contaminated with plutonium because of minor trials that included the burning of the carcinogenic element. In total, the scientists discovered more than 48.5 pounds of plutonium-239 around the site, which has a half-life of more than 24,000 years. Between 1996 and 2000, most of the Maralinga site was cleaned to levels considered safe, and it was returned to the Tjarutja in 2009. The Australian government also paid 13.5 million to Indigenous communities there in 1994. However, community leader Mima Smart told BBC News that most people had not been compensated sufficiently.

Despite the return of the land and the assurance of safety, Smart also said she had no desire to return. "Too many bad memories," she said. Local plant and animal life seem to agree with her. "The grass here only ever grows a few inches," Robin Matthews told BBC News. "Even the birds and the kangaroos still stay clear of this area." It's still possible to see evidence of the violence of the blasts in the bright glint of instantly-glassed sand and the green sheen of the iconic orange outback sand.

Collisions

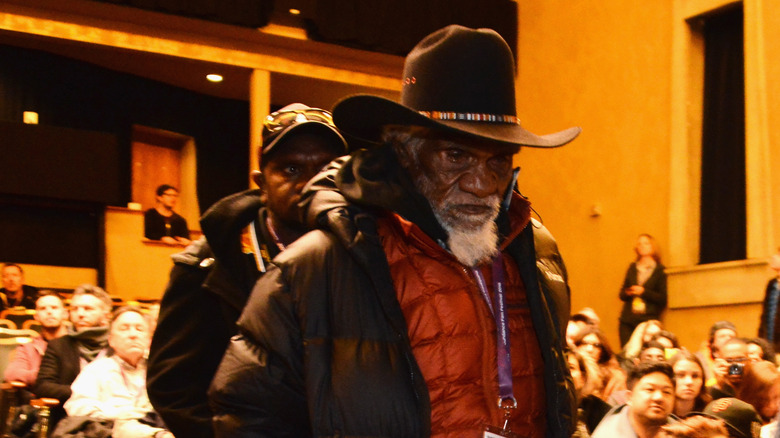

Despite the lingering health impacts that have plagued test survivors, Nyarri Nyarri Morgan has lived a long life. When he was around 80, he even had a chance to share his remarkable story with the world with the help of director Lynette Wallworth (via LynetteWallworth.com). Wallworth first heard of Morgan when she was invited to film the Maru community and mentioned that she had been to Maralinga. Members of the community then said she needed to talk to Morgan. "What he saw, and how that impacted him, I think he'd been waiting his whole life to tell it," Wallworth said.

That telling came in the form of "Collisions," a virtual reality experience shot with 16 GoPro cameras attached to a special device designed to film in 360 degrees, according to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. It premiered in 2016 at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. For the premiere, Morgan, who had never left his home territory and did not even have a birth certificate, got his first passport and boarded his first airplane, according to LynetteWallworth.com. Wallworth told Australian Broadcasting Corporation how Morgan was glad the story would now survive him. "[T]he loss of the story is the loss of us understanding our own country," she said.