Chilling Stories From San Quentin

Agree with it or not, the death penalty is a well-established part of American history — and for a lot of that history, the nation's most infamous death row was at San Quentin. And it's been that way for a long, long time — the first prisoner execution took place in 1893.

In 2022, the Los Angeles Times reported that the 737 inmates being held there were going to be slowly moved to other facilities across the country, as the state of California was rethinking their stance on the death penalty. At the time, it had been 16 years since an execution, and those living on death row were existing in a weird sort of limbo.

While the death penalty has always been incredibly polarizing for those on the outside, for those inside, it's just as real as the walls and the wire that surround them. And here's the thing: U.S. citizens had been condemning people to death long before the idea was formalized into law, with newspapers documenting cases where angry mobs simply dragged an accused to a conveniently-located tree and strung 'em up. Those were the heady days of the mid- to late 19th century, when a hangin' was an afternoon event. Something to watch.

Those days passed into something less public, but no less chilling — so let's look at some snapshots of one of America's most notorious prisons.

Test runs of the gas chamber

There have been three methods used to execute San Quentin's death row prisoners, says the Los Angeles Times: Hanging, the gas chamber, and lethal injection. For several decades, San Quentin shared execution duties with Folsom, but after the gas chamber got fully up and running in 1938, it became the go-to.

And getting things running wasn't easy. The very first to die inside the chamber that came to be known as the smokehouse was a pig — and it took a shocking 35 minutes for the creature to succumb to the effects of the gas. It wasn't exactly what had been promised by the manufacturer when it was installed: Earl Liston of Eaton Metal Products Co. had told California officials that the gas chamber would take just 15 seconds to kill (via the LA Times). Warden Court Smith had doubts from the beginning, saying — after a timing test that involved two guards — "Hanging is bad enough. But this — it's terrible."

Still, it was put to almost immediate use in the execution of the survivors of a Folsom prison riot that left four dead, including the prison warden. Newspaper reports of the time (via Executed Today) report that spectators were traumatized by the sight of the dying men — including Albert Kessell, who uttered the final words, "It's bad."

Amos Lunt, hangman

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation starts the story of Amos Lunt with a disclaimer: At the time he was employed as San Quentin's hangman, not only was little known about the connection between trauma and conditions like depression and PTSD. Lunt was a military veteran of the Civil War, and a former police officer; when San Quentin created the role of Chief Deputy Warden in 1894, Lunt was the first to be responsible for overseeing the prison's executions. The first for Lunt was the death of a man named Lee Sing. Condemned to die after being convicted for first-degree murder, he was hanged under Lunt's supervision.

Lunt would go on to oversee a total of 20 executions over the course of the next few years, and when Frank Arbogast was brought in to replace him in 1899, Lunt warned him of the specters that kept him awake at night, saying, "They are after me. There are several under the bed now. ... it's only a matter of time until they get me."

A newspaper preserved by the Santa Cruz Public Library reported that Lunt — who had been reassigned to guard duty — had begun to suffer from hallucinations. By 1901, he had been committed to the State Asylum for the Insane at Napa, where the Sausalito News reported that he was drifting closer to death with each passing day. He ultimately did die there, in September of the same year.

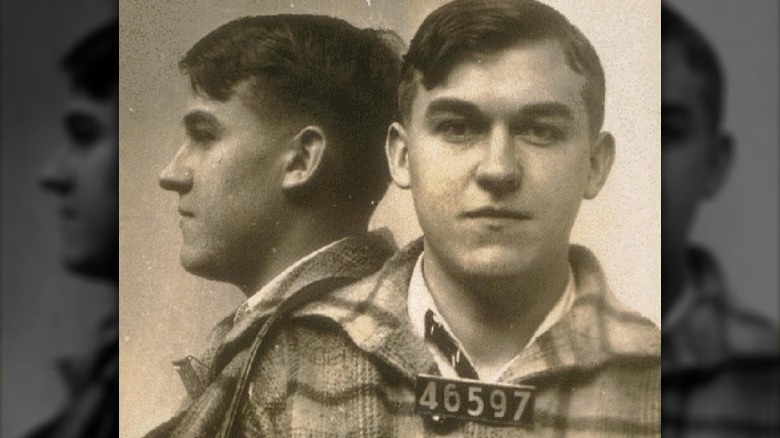

Dallas Egan, dancing to the hangman

Dallas Egan's crimes weren't the kind of thing that would be getting him his own Netflix series anytime soon. He plied his trade — which was largely based in robbery — during the Great Depression, and things really went sideways for him and his gang in 1932. That, says the Los Angeles Times, is when they were robbing a jewelry store to the tune of $5,000. (Adjusted for inflation, that's about $103,000 in today's money.)

Egan was keeping a lookout over the shopkeeper and clerk when a man — 76-year-old William Kirkpatrick — had the phenomenally bad luck to choose that time and place to stop and check his watch. Egan shot him at almost point blank range through the window, and when he was arrested shortly after, he made no secret of the fact that he was done with society, and that he'd been happy to kill anyone he thought might get in his way.

After his guilty plea, Egan declined a trial to judge his sanity — with a few conditions. He wanted to be executed at San Quentin: "I can think of nothing better than the drop through the gallows. I'm a criminal at heart and I want to be hanged." So, he was. After a hearty breakfast, a cigar, and some whiskey, he was handcuffed and escorted to the gallows — and he danced his way there. He climbed the steps by himself, and had no last words.

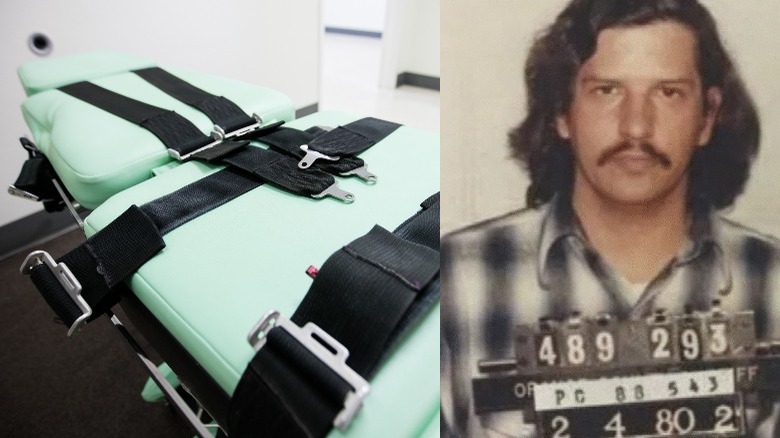

William Bonin, the Freeway Killer

In 1996, San Quentin changed the way they executed those who were making their final walk down death row — and the first to be executed via lethal injection was convicted serial killer William Bonin. Known to the media as the Freeway Killer, Bonin confessed to the torture and murder of 21 men and boys in the late 1970s and early 1980s. According to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, Bonin mainly chose his victims out of convenience: a European student backpacking across the U.S., a teen walking through a supermarket parking lot, and several hitchhikers ... among many others.

The Los Angeles Times reports that even as protesters and death penalty supporters gathered outside, Bonin gave an interview to a local radio station, had his last meal — pizza and ice cream — and watched "Jeopardy" on the night before his execution. While he said that he had come to terms with the fact that his life was about to end with a needle, he had some chilling last words for those who gathered to watch him die. He told the crowd — which included the relatives of some of his victims — "They feel that my death will bring closure. But that's not the case. They're going to find out."

By the time Bonin's execution happened, he had been on death row for 13 years.

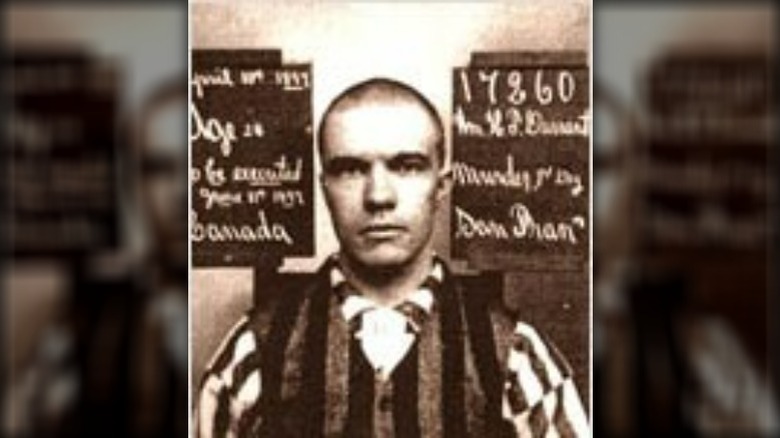

Theodore Durrant, Demon of the Belfry

Theodore Durrant lived in San Francisco in the late 19th century. He was the assistant Sunday school director for the Emmanuel Baptist Church, which is why he had access to the church's belfry — where he left the women he killed. He was also a student at Cooper Medical College, which is where he got the idea to elevate the bodies on wooden blocks to slow down decomposition.

Blanche Lamont and Minnie Williams were murdered with such viciousness that SF Gate says it earned Durrant a comparison to Jack the Ripper — so it's not entirely surprising that along with the guilty verdict was a death sentence.

Durrant wasn't alone when it came time to mount a defense, and he'd already been sentenced to hang when his father decided he needed to go inside San Quentin and film what his son's life had become. After getting special permission from the warden, Durrant's father went inside to film scenes that were mostly choreographed to highlight Durrant's sensitive side — smelling roses, picking flowers, that sort of thing. When it was shown publicly, the headline of the San Francisco Call summed it up best, simply reading "Warden Hale angry."

The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation says that he wasn't just angry, but super angry when he found out that his daughter had been caught on film, too. He got exhibition of the film stopped, and none of it helped Durrant: He was hanged on Jan. 7, 1898.

Time spent in the Adjustment Center

Death row might be the most famous part of San Quentin, but there's also the Adjustment Center. That 1984-esque name belongs to the ultra-secure section of the prison that's used to house inmates that are deemed a threat to the security of the prison... pre-COVID, at least. Post-COVID, The American Prospect reports that it's still being used as a quarantine and medical facility.

Wayne Hughes was moved there when he tested positive for COVID in 2020. Since then, he's been sent back several times: Once, he said, when someone heard him clearing his throat. While safety measures to prevent the spread of COVID are necessary, inmates have argued — and in some cases, sued — over what they say is the prison's use of strict solitary confinement for a medical treatment facility.

Conditions, they say, are awful: Inmates are handcuffed while being escorted to the showers, and woken every 30 minutes by a guard with a flashlight. A lawsuit described cells with perpetually running water that weren't cleaned between inmates — and when one asked for cleaning supplies, they were told there were none kept in the AC.

Some inmates have claimed that they've been kept there in spite of negative COVID tests, and Hughes sums it up like this: "You'll get sick just from being in that filthy place. AC is so unsanitary that the medical staff should be ashamed for even accepting that for quarantining people."

Robert Rattlesnake James, black widower

First, an in-a-nutshell summary of the life of Major Raymond Lisemba. That was the name he was given when he was born in 1895, but after his first marriage (which ended in divorce) and his second (which ended in divorce after the father of his pregnant lover caused an uproar in town), he fled west and changed his name to Robert James.

After taking out a life insurance policy on Wife 3 (worth about $289,000 in today's money), he bludgeoned her with a hammer and staged a car accident. She survived — but she didn't survive when he drowned her in a bathtub. After taking his niece as his lover, he tried it again — Wife 4 didn't sign the insurance paperwork — so he moved on to 5. She was killed by a combination of rattlesnake bites and drowning, and the Los Angeles Times says that's ultimately how he ended up in San Quentin.

While he was on trial, Echo Press says that he posed for media photos — he was even given a saw and told to make it look like he was trying to escape. Escape, he did not. He was hanged in San Quentin in 1942, and became a case that demonstrated the importance of the right rope: He slowly suffocated when they used one that was too long.

Building — and dying in — the gas chamber

When the Los Angeles Times took a look back at the history of San Quentin's death row in 1990, 501 people had been executed there. They all had their stories, but there were none quite like the story of Alfred Wells.

Wells, they wrote, was being held in the non-death-row section of San Quentin on a burglary conviction when they started installing the gas chamber. He — alongside other inmates — helped install it, and was overheard to remark, "That's the closest I ever want to come to the gas chamber."

Wells was eventually released on parole, and that's when he started hooking up with his half-sister. Their entire family had a major problem with the relationship, and Wells responded by killing his half-brother and two other women. That kicked off a massive, month-long manhunt for him, and when he was arrested, he soon found himself back in San Quentin. This time, he was on death row and waiting for his turn in the gas chamber that he helped install.

By all accounts, he was a nightmare prisoner. It wasn't until he became pen pals with the warden's wife that he started to become not-so-violent, but his time was up shortly afterwards, and his execution was carried out.

Douglas Ray Stankewitz, death row's longest-serving resident

In 1978, 21-year-old Theresa Graybeal was buying food for her dogs when she was carjacked by a group of four people who told her that they needed to get to Fresno to buy drugs. Then, they pulled over outside of Fresno, and Graybeal would die on the side of the road there, from a gunshot wound to the head.

Five people were arrested: According to Indian Country Today, two were sentenced to 12 years, one was given five years, another — a minor — was granted immunity for his testimony, and Douglas Stankewitz was convicted of being the one who pulled the trigger. He was sentenced to death.

Stankewitz has long maintained his innocence. While he was in the car that night, he says (via The Marshall Project) that he wasn't the one who killed her or carjacked her. Fast forward to 2012, and new information meant the sentence was reduced to life without parole, a reduction that took seven years to happen. Fast forward again, and Stankewitz is San Quentin's longest death row resident.

When he gave an interview in 2022, he'd been there for 44 years — and he'd only felt grass five times. He counted his time in isolation in years (including seven for refusing to go against his Native American beliefs and cut his hair), didn't have a mattress anymore, and has the same day-to-day he has for decades. As of the interview, he was waiting to find out if he could be paroled.

Gordon Stewart Northcott, the Chicken Coop Murders

While the name Gordon Stewart Northcott might not be instantly recognizable, his crimes might be a little more familiar: They were portrayed in the Angeline Jolie movie "The Changeling." That, says People, was the film about a mother who is convinced that the boy who's returned to her as her son is an imposter — and she was right.

The real boy — Walter Collins — was never found, and was believed to be one of Northcott's victims. When his crimes came to light, southern California (and his native British Columbia) was shocked by the morbid tale that came from the chicken coops on his Depression-era farm. The remains of several boys — including one who was shot, beheaded, and never identified — were discovered on the property, and it was estimated he had killed somewhere around 20. He was found guilty and sentenced to hang at San Quentin (via Executed Today).

When Northcott's turn to meet his maker came, the Los Angeles Times says his hanging went down in San Quentin's books as being one of the most difficult. He broke down so completely that guards had to drag him first to the gallows then up the 13 stairs, and he reportedly screamed before he hanged, asking those in attendance to pray for him. It was far removed from the time he'd spent in prison up until then: According to the Healdsburg Tribune, he had previously danced and sang in the faces of mothers who wanted to ask him what their sons' last moments had been like.

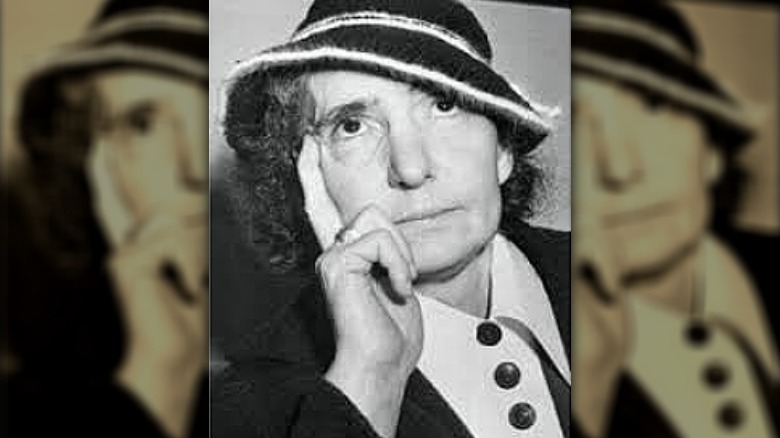

Juanita Spinelli, the Duchess

Juanita Spinelli was one of only a few women who were ever executed in San Quentin's gas chamber, and according to SFGate, the hardest thing about telling her story is figuring out where fact ends and fiction begins.

What is known is that Spinelli ran something of a school for up-and-coming criminals, teaching them all the basic skills they would need to know to live a life on the other side of the law ... and then, turning them into her own gang of young thugs. They focused more on robbery than on killing, but the 1940 shooting death of a man named Leland Cash kicked off a series of events that ended with Spinelli being arrested, convicted of the murder of one of her own gang, and sent to death row — in spite of her attempts to blame her daughter for the murder, a detail that's going to be important.

The idea that a woman was going to be executed was hugely controversial, even among her fellow death row inmates. They petitioned for a stay of execution, and some even volunteered to take her place in the gas chamber.

Their efforts were all for naught. Spinelli was executed on Nov. 22, 1941, and when she died, she carried a single thing with her: a photo of the daughter she'd tried to pin her crime on.

Aaron Mitchell, the end of death row... at least, for a while

The Madera Tribune reported that Aaron Mitchell — convicted of killing a police officer — died in San Quentin's gas chamber in April of 1967. A full 18 years later, the Los Angeles Times argued that his execution had been so traumatic that it was a major part of the reason that no executions had been carried out since.

Things started out badly: Mitchell attempted to cut his wrists with a piece of metal the day before he was going to be executed, and another prisoner recalled, "Mitchell had a wild look in his eyes and began shouting: 'I am the second coming of Jesus! I am the son of God!" Guards got him into his cell beside the gas chamber and prison doctors stopped the bleeding, but that night, Mitchell stripped off his clothes, re-opened the wounds, and stood in his cell, arms out, chanting, "This is the blood of Jesus Christ ... I am going to save the world."

The next day, he was escorted to the gas chamber and executed. His last words were, "I am Jesus Christ!" and afterwards, no one could quite decide if — as psychiatrists had ruled — it was an act, or if the stress of his imminent execution had caused him to have a mental break.

That — coupled with questions about the competency of Mitchell's defense — led to a pause in executions and questions that still linger.