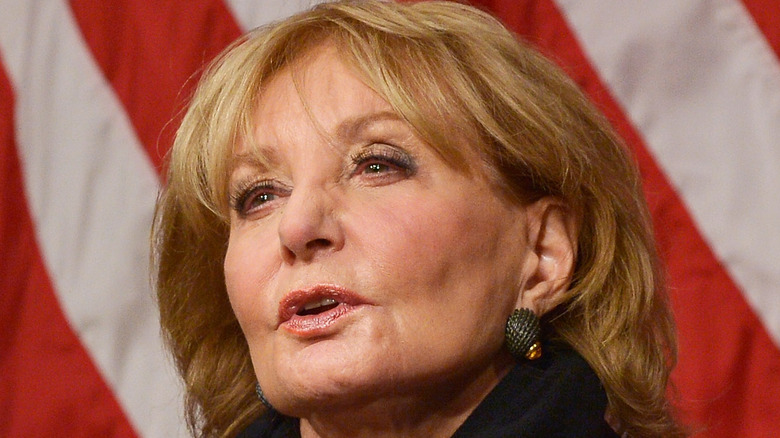

The Life And Career Of Iconic Journalist Barbara Walters

The toll on the ranks of public figures was paid right up until the end of 2022. Queens, popes, actors, and sports stars of international renown all went to their final rest. On December 30, one of America's most notable journalists of the 20th century joined the list. Barbara Walters died at 93 in Manhattan, according to her obituary in The New York Times.

At the time of her death, Walters had been retired for eight years from her most prominent platform, the talk show "The View" which she co-created. But her relevance to American journalism hadn't faded. "The View" remains one of the most notable morning talk shows on television. Long before that, Walters broke ground for women as on-camera interviewers and reporters. Her approach to one-on-one interviews attracted criticism over the years, as did Walters' own celebrity and ambition. But she broke news through her interviews, and her style helped reshape the image of the news anchor.

It was a long road traveled by Walters, whose early life touched the world of celebrity but was far from stable. Here is a look back on the life and times of Barbara Walters.

She had an unsettled home life

Barbara Walters was born on September 25, 1929, in Boston. Her parents, per her obituary in The New York Times, were Lou Walters and Dena Seletsky Walters. Both were the children of Jewish refugees escaping persecution on the European mainland. Lou's family relocated to England, and he retained the accent throughout his life. He first met Dena when she was working at a neckwear shop.

In her memoir, "Audition," Walters described her parents' marriage as complicated. While superficially compatible, they had little in common. Lou was emotionally distant at home but indulged in cards and books, while Dena led a very pragmatic life that made ample time for her children. Walters never saw her parents be affectionate with one another and never heard them discuss her older brother Burton, who died of pneumonia before her birth. Lou's work and habits made for a rocky financial situation that saw him clash with his wife. Despite the tensions, they remained married until death.

Walters was close to her mother, but had complicated relationships with both her father and her older sister Jacqueline. Jackie, as she was known to the family, suffered from mental disabilities. In the prologue of "Audition," Walters admitted to feeling embarrassed of her sister while also expecting to become her caretaker one day. She attributed her work ethic to her mixed feelings of love and shame for her sister. Jackie's family cared for her, but poorly understood her impairment. Jacqueline Walters died in 1985 (via Biography).

She grew up around celebrities

Long before she was interviewing celebrities on "20/20" and her special segments, Barbara Walters was in contact with the rich and famous. Her father, Lou Walters, worked around them. Per his obituary in The New York Times, the elder Walters was the unlikely mind behind the Latin Quarter nightclubs in Boston and New York. He maintained ownership of the New York location for 16 years, and returned as its manager after selling it. Walters also established clubs in Miami and worked for venues in Nevada.

Lou came to the nightclub business by way of vaudeville. His professional life began in the booking office of a New York theater and developed until he had his own agency. After moving into management of his own clubs, Lou emphasized entertainment and elegance. He called in talent ranging from Frank Sinatra to Milton Berle to put on shows for his guests.

Later in life, Walters attributed her father's connections to her own attitude toward performers. "I was never in awe of celebrities," she told Variety, "because they worked for my father." Another lesson her father's career left her with was the instability of a life connected to celebrity; Lou Walters made millions, but lost just as much over the years.

She had several interactions with a mobster

Her father's career meant that Barbara Walters moved around a lot as a child. Per the Miami Herald, after her birth in Boston, Walters' family put in several stints in south Florida, where Lou Walters operated two nightclubs. The Colonial Inn, located in Hallandale, was the site of a Miami Beach High School dance at Walters' insistence, and was later allegedly sold by her father to the notorious Meyer Lansky.

That sale, if it happened, wasn't the only connection between the Walters and organized crime. Her first kiss reportedly happened right behind Al Capone's Palm Island mansion. And before World War II, while staying across the street from Lou's Latin Quarter nightclub, the Walters shared space with a man named Bill Dwyer.

A young Barbara Walters didn't know much about Dwyer, who sometimes took her on outings to the park or the racetrack. Later, per her memoir "Audition," she learned that he was a Prohibition-era mobster. He was also once the owner of the Latin Quarter before Lou took control of it. The elder Walters felt it better not to push his luck in getting Dwyer out of the house across the street, and the mobster and his chauffeur stayed for a year.

She faced unwanted advances at the start of her career

Barbara Walters first entered the workforce in 1951 after graduating from Sarah Lawrence College. She got a job as an advertising agency secretary, and by her own admission (via NPR), she didn't get the job because she was a dictation ace. She got the job because she had a pair of legs that caught her boss' eye.

Uncouth hiring decisions and aggressive attention from male superiors were unfortunately standard office procedure in the 1950s. When Walters made the leap into news broadcasting by taking a job with a New York NBC affiliate, she fell into an affair with a married man who later ambushed her when she came home from another date. Walters was also obliged to pick up the slack when her boss at the affiliate went off drinking — a regular occurrence.

Discrimination extended to the matter of pay; Walters' requests for a raise were met with protestations that, with so few women employed, she shouldn't object to the pay she had. And when she first joined NBC's "Today" as a writer, she told Variety, she was the only woman there. There were no opportunities for others to join her either; there was only room for one woman, and the one hired would stay there until she left.

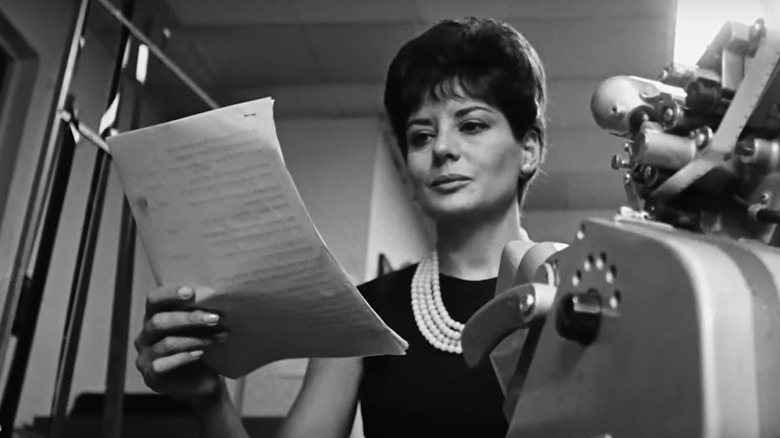

From Today Girl to co-host

In 1961, according to The New York Times, Barbara Walters joined the staff of NBC's "Today" as a writer. She was soon making her first on-air appearance in what was then known as a "Today Girl" position, a woman correspondent who presented stories on stereotypically feminine topics. Walters pushed to expand the range of her coverage, and by the middle of the decade was attracting notice from her peers in the newspaper world.

What she did to revamp the role of women reporters on "Today," Walters repeated on a larger scale when she inherited the morning talk show "For Women Only." It was an NBC affiliate public service program that aired directly after "Today" in New York and came with an offer of control and taping convenience, per Walters' memoir "Audition." She changed the name of the series to "Not For Women Only" to signal her broader intentions as host. The rechristened show diminished its focus on public service, but it was a ratings hit. Walters credited it for inspiring later talk shows, her own "The View" included.

Walters remained connected to "Today" even after beginning work on "Not For Women Only." By that time, she had been in the press pool that followed President Richard Nixon to China. She was, for all intents and purposes, the co-host of "Today," but wasn't given the title until 1974. Per the BBC, she was the first woman officially made a host of an American news program.

She clashed with male co-hosts and presenters

Breaking glass ceilings tends to upset those who contributed to building them. As one of the first prominent female journalists on television, Walters developed complicated relationships with her male co-hosts and counterparts. One of her early associations was pleasant and long-lasting. She and Hugh Downs, who was the host of "Today" when Walters was hired as a writer, amicably worked as co-hosts and later partnered on ABC's "20/20." They were friendly off the set as well (per ABC News).

Walters had a much more difficult time with Frank McGee, Downs' replacement on "Today." Speaking to the Television Academy Foundation, Walters related how McGee insisted that she not be allowed to ask a question of prominent political guests until he had asked three. "He was pleasant to me on the air, [but] he wasn't enormously respectful off the air," said Walters. To circumnavigate McGee's restrictions, she began working to acquire exclusive interviews outside the studio.

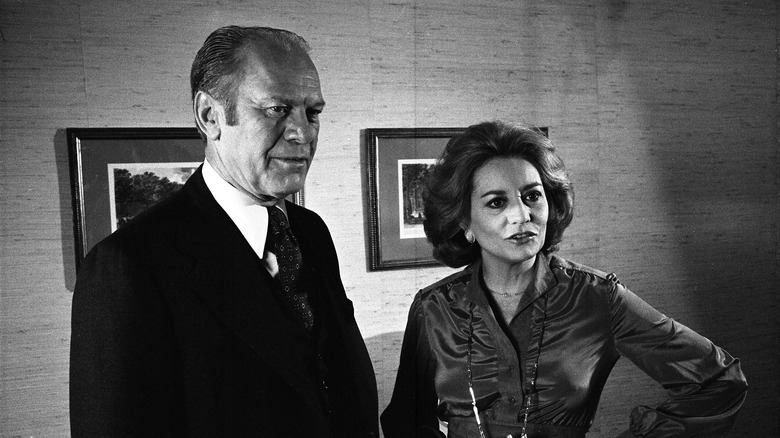

When Walters moved to ABC in the 1970s, she butted heads again with a male co-host. This time it was Harry Reasoner, anchor of the evening news broadcast. Reporting in The New York Times from around the time of Walters' hiring alluded to dissatisfaction on Reasoner's part with Walters' salary ($1 million a year) and her approach to interviews. Reasoner favored a more formal approach to journalism compared to Walters' more personality-driven style.

The Barbara Walters Specials

After breaking ground at NBC by becoming American journalism's first female co-host on television, Barbara Walters moved to ABC. She won the highest salary then paid to a news anchor in the move (per The New York Times obituary), though her stint on the evening news was short-lived. ABC shook up the format and made Walters a contributor. But it was in that role that she left one of her most notable marks on American television.

Starting in 1976, Walters produced the "Barbara Walters Specials," probing and informal interviews with a range of wealthy and notable figures from around the world. Grilling celebrities helped make Walters one herself. Her dogged efforts to coax highly emotional revelations out of her subjects — while keeping herself in the spotlight with them — wasn't always applauded. But the specials were widely viewed, and her approach to interviewing public figures has been widely imitated since (per the Los Angeles Times).

After her death, The Hollywood Reporter highlighted some of Walters' more famous (and infamous) interviews from across the years. "Barbara Walters Specials" was Christopher Reeve's platform of choice when he decided to speak publicly after his accident, and Walters' interview with Monica Lewinsky attracted over 48 million viewers. But she once said that the best introduction to her style of working was her interview with Mike Tyson and Robin Givens.

Barbara Walters vs Gilda Radner

Whatever the common saying teaches, imitation is not always taken as flattery. As Barbara Walters and her sit-downs with celebrities increased her own public profile, she became a ripe target for comics and parodists. Among the most famous spoofs of Walters was Gilda Radner's Baba Wawa character on "Saturday Night Live." But the target of the joke took a long time to laugh.

Per The New York Times, Baba Wawa didn't just poke fun at Walters' speech. The character also commented on Walters' work as a journalist. Radner and the "SNL" writers weren't shy about noting the tabloid quality of some of the scoops and responses Walters got out of her interviewees. The parody was a sore spot for Walters until, she told the Television Academy Foundation (via YouTube), she caught her daughter watching a Baba Wawa sketch one night. As she railed against the program, her daughter cut her off with four words: "Oh Mommy, lighten up."

As for Baba Wawa's exaggerated portrayal of Walters' pronunciation of Ls and Rs, the anchor herself insisted it wasn't due to a speech impediment. "I think there are other people who don't pronounce their L's too well," she told The New York Times. "I also have a leftover Boston accent. I say cah, I don't say car."

Her interviewing style was heavily criticized

Was it really a Barbara Walters interview if someone didn't break down crying? Walters' talent for extracting personal and often emotional anecdotes and confessions was one of her calling cards and contributed to her own persona as an aggressive yet empathetic newswoman. But her style was the frequent target of criticisms. Her own prominence in her interviews, her alleged lack of distinction between celebrities and heads of state in her conduct, and her packaging of emotional content as hard journalism were all excoriated at one time or another in her career (per the Los Angeles Times).

Some criticisms were more personal. Among Walters' interviewees was Brooke Shields, who sat down with the journalist in 1980 to discuss her provocative Calvin Klein jeans ads. Only 15 at the time, Shields was deeply uncomfortable with the questions she was asked, some concerning her sex life. In an interview with "Armchair Expert," she claimed that Walters' conduct fell short of the definition of journalism.

In its obituary, The New York Times shared some of Walters' regrets about her career as an interviewer. Most of her regrets concerned people she couldn't get to sit down, or the shifting definition of celebrity applying to people Walters didn't think were worth spotlighting. But she also admitted to being overly aggressive in trying to pull Ricky Martin into discussing his sexuality, and to not revealing that Betty Ford was drunk when she gave Walters a White House tour.

She kept her religious views private

Barbara Walters' interviews were sometimes noted more for their sensational emotional content and her own manner than for the content discussed. But she was a determined journalist, and she did get into substantive discussions. And she was prepared to keep certain aspects of her life and thoughts out of the spotlight for the sake of journalistic integrity.

In a joint article by The Washington Post and Newsweek from 2006, Walters shared one such subject ahead of an ABC special about God. Titled "Heaven: Where Is It? How Do We Get There?", the show featured interviews with clergy, an unsuccessful suicide bomber, scientists, and the Dalai Lama. In promoting the show, Walters was open about her own religious background, or rather the lack of one. While both her parents were from Jewish families, her father was an atheist and her mother was uninterested, leaving Walters with no education nor tradition in faith. Her interest and observance of different Jewish or Christian traditions as an adult varied depending on her marriages and relationships and, prior to producing the special, she had little awareness of her friends' religious beliefs.

The ABC special made Walters more considerate of religious matters, and she told The Washington Post and Newsweek that she considered faith in God and heaven to be deeply comforting. But she didn't volunteer her own beliefs, saying that it would be inappropriate as a journalist to bring that into her work.

The View's long legacy

Barbara Walters may be gone, but one of the cornerstones of her legacy on network television lives on. Per her obituary in The New York Times, "The View," which Walters co-created and co-hosted for years, had 26 seasons and counting as of December 2022. Besides its longevity and the innovation it represented for morning talk shows when it first appeared, "The View" has often made news in its own right.

Walters and co-creator Bill Geddie debuted "The View" in 1997, with the goal of exploring hot button issues of the day through varying perspectives offered by the all-female panel (per ABC News). Besides Walters herself, prominent hosts have included Joy Behar, Rosie O'Donnell, Meghan McCain, and Whoopi Goldberg. Over the years, the women of different viewpoints have often clashed with guests and with each other, as when O'Donnell and Elisabeth Hasselbeck became so heated in their discussion about the Iraq War that their co-hosts faked storming off the set to break the tension.

Behar, who has been a co-host for nearly every season, discussed with The New York Times the shifting perceptions of "The View" in 2019. Initially perceived as a light talk show, the show has increasingly been perceived as an influential news program, as much for the more personalized and informal nature of its panel as its reach among viewers. And it's encouraged imitators, CBS' "The Talk" among them.

She had numerous marriages and affairs

Work and home did not always gel nicely for Barbara Walters. Her confidence, ambition, and tenaciousness in journalism was not always matched in her private life, as she discussed with the San Francisco Chronicle while promoting her memoir "Audition" in 2008. From an often isolated childhood to a sometimes challenging experience of motherhood, Walters was frank about her personal struggles. And that included her relationships with men.

Walters was married four times to three men. Her first husband (per "Audition") was Robert Katz, though the marriage didn't last long. With second husband Lee Guber, she adopted a daughter. Her third husband was the one she married twice: Merv Adelson. Per his Deadline obituary, they were first married in 1981 and divorced three years later. They remarried in 1986 and stayed together until 1992.

Between marriages and throughout her life, Walters had several high-profile boyfriends and affairs with married men. She revealed in "Audition" that she had a years-long relationship with Edward Brooke, the first Black man since Reconstruction elected to the U.S. Senate. During the affair, Brooke was married and Walters continued to see other men casually. It was Walters' friend Pete Peterson who convinced her that a scandal would be devastating to them both should the relationship be discovered and so she should end it.