The Tragic True Story Behind Hotel Rwanda

The brutal Rwandan genocide that took place in the 1990s led to the murder of around 1 million people during a 100-day-long bloodbath (via the New York Times). Decades of violence and a flood of hate-filled propaganda culminated in an attempted mass extermination of the Tutsi clan — a long-resented minority group in Rwanda (via the University of Minnesota). Although the genocide was carried out with ruthless efficiency, a lucky few survived the killings, including over 1,200 people who lay low at the Hôtel des Mille Collines in Kigali. Against all the odds, and after 11 weeks of waiting, the hotel's occupants emerged miraculously unscathed.

In 2004, the events that unfolded at the hotel were retold in the award-winning film "Hotel Rwanda," a movie that made the hotel manager into a hero. Today, the film's version of events is deeply controversial and the true story has never been definitively established.

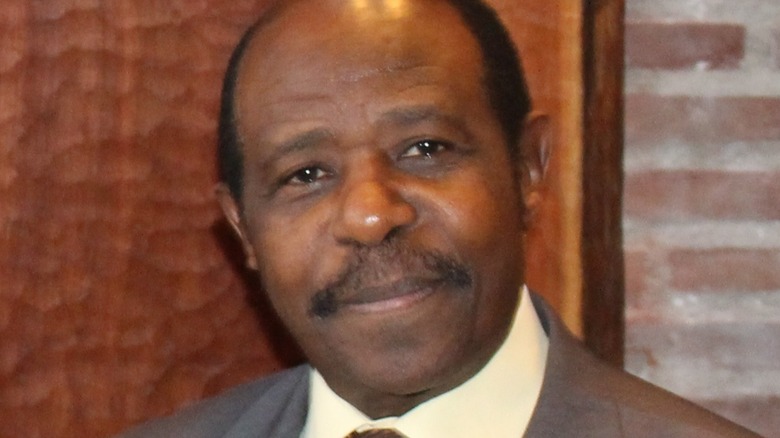

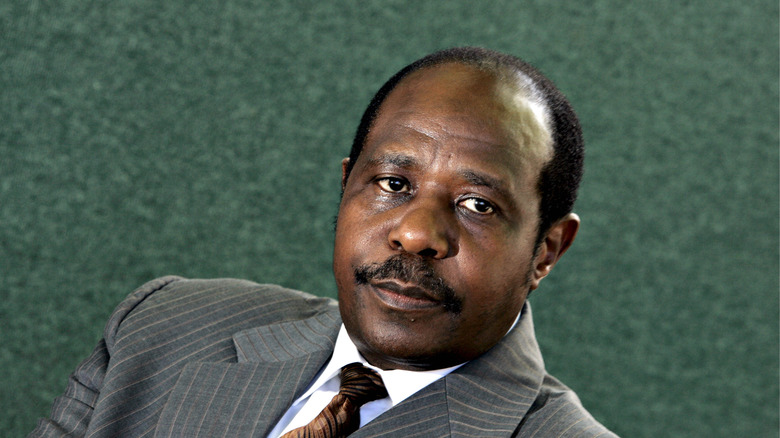

Although many witnesses have come forward to tell their stories, the details remain murky, and political intrigue has added to the confusion. The infamous hero hotelier Paul Rusesabagina is now a figure of hate in some circles and was jailed on terrorism charges in 2021 (via CNN). Is "Hotel Rwanda" an inspiring story of human kindness, or a work of pure fiction? And have the real heroes gone unnoticed?

Tensions between the Tutsi and the Hutus

Why did the Tutsi people need shelter in the hotel in the first place, and what events sparked the genocide in 1994? The tensions that led to the Rwandan genocide are complex and have a long history. Rwanda has been plagued by serious political unrest since before the end of colonial rule in the 1960s. Prior to colonialism, the so-called "Tutsis" ruled over the Hutu majority in Rwanda. There are some local legends surrounding the origins of the Tutsi that suggest they represent a different ethnic group — but it has never been proven is probably not true. According to Human Rights Watch, the word "Tutsi" once just meant "rich person," but the story of the group's origins has been distorted over time through myths created by the ruling class — and through persistent misreporting in the media.

Whatever the truth may be, by the 1950s, Rwanda effectively ended up with a caste system under Belgian colonial rule, when Western officials reinforced what they understood to be an ethnic divide between the two groups. Hatred for the ruling Tutsis culminated in the 1959 Hutu revolution, an event that reversed the existing order of things and put the Hutus in charge (via the United Nations). Many Tutsis went into exile after the revolution to avoid persecution, while many others joined the rebel group, the RPF — the Rwandan Patriotic Front.

Following independence in 1962, sporadic violence between the two groups became the norm in Rwanda, and a civil war finally broke out in 1990 (via Minnesota University).

100 days of the tragedy

Things finally reached a head in 1994, the year "Hotel Rwanda" is set. The Hutu president of Rwanda was killed in a plane crash along with the president of Burundi when a rocket hit his craft and sent it hurtling into the ground (via History). To this day, nobody has ever discovered who fired the rocket — but at the time, Tutsi militants were blamed for the assassination.

Although the Rwandan government had just ended a war with the Tutsi RPF the year before, anti-Tutsi-feeling had reached fever-pitch, due to an explosion of anti-Tutsi hate speech on the radio (via the University of Minnesota). The day the president was killed, the Rwandan army immediately began a campaign of revenge setting up roadblocks and killing civilians. The army's reaction was not a spontaneous act of violence — militant groups had been planning a genocidal slaughter for at least several months before the president's murder. To the horror of the international community, they moved with alarming efficiency across the country (via Vox).

In the days that followed, Rwandan soldiers aligned themselves with several extremist anti-Tutsi militia groups — such as the Interahamwe hate group — who helped to carry out the genocide. Together they went from town-to-town, butchering civilians with guns, clubs, and machetes. Over the course of a 100-day period, something in the region of 1 million people were killed, including hundreds of thousands of Tutsis, many sympathetic Hutus, and the moderate Hutu prime minister.

Who was Paul Rusesabagina?

Enter Paul Rusesabagina, a Rwandan hotel manager who found himself in the midst of the horrifying sectarian violence as it unfolded. Rusesabagina would later become the protagonist in the Hollywood take on the Rwandan genocide, "Hotel Rwanda" — although the details of his story have been questioned ever since. Whatever the truth, one thing is certain — every single person who took refuge in Rusesabagina's establishment, the Hôtel des Mille Collines, survived the massacre.

Before entering the hotel business, Rusesabagina trained to be a priest, but he has repeatedly stated that it was his upbringing as much as his religion that led him to his alleged role as a peacemaker during the catastrophe (via Penguin Random House). Rusesabagina came from an unusual mixed Tutsi-Hutu family and married a Tutsi woman as an adult. Because Rwandan society is patrilineal, and his father was a Hutu, Rusesabagina was considered a Hutu himself and spared certain death (via NPR).

During an interview with NPR, Rusesabagina stressed that he was used to socializing with both Tutsis and Hutus and inherited a strong sense of justice from his father.

Rusesabagina calls for help

According to Paul Rusesabagina, on day one of the genocide, Tutsis were already being massacred on his front doorstep. By the end of the day, his house was already packed with 26 visitors, all hiding from the machete-wielding thugs outside (via NPR). Rusesabagina's version of events should be taken with a pinch of salt, but according to his own account, he immediately got on the phone with the U.N., which was working in the area following the Rwandan civil war.

Rusesabagina claims he was given short shrift by a U.N. peacekeeping major who informed him of the dangers U.N. troops were facing and told Rusesabagina in the event that the killers showed up in front of his house his best bet was to escape through the backdoor. Eventually, soldiers working for the interim government came through for Rusesabagina instead, escorting his family and guests to the Hôtel des Mille Collines. Government workers were staying in another hotel he was responsible for, so it was in their interest to offer him protection.

The U.N.'s inability to mobilize and save people during the genocide has come under fire many times ever since. Thousands of peacekeeping troops were stationed in Rwanda following the end of the civil war, but for the most part, they pulled out of the country and did very little to intervene (via The Conversation). The former secretary-general of the U.N., Ban Ki-Moon admitted, "Troops were withdrawn when they were most needed." On the other hand, the few troops that did remain exercised their limited authority with great courage.

Time to talk

According to his own retelling, once he got to the hotel, Paul Rusesabagina had to keep various bands of roaming killers at bay. The manager recounted that he made frequent use of his alcohol store, as well as cold hard cash, to bribe the local militia (via Penguin Random House). Rusesabagina's invaluable phonebook also got the group out of trouble on multiple occasions. After he spoke to the Belgian Press about the hotel, for example, the Rwandan government agreed to supply the building with a police guard (via the University of Michigan). When the hotel was inevitably surrounded by the military anyway, another desperate round of phone calls successfully summoned a police colonel, who shooed the soldiers away.

Hutu military men knew the four-star establishment well, and Rusesabagina claims that he used his charm to flatter every soldier he knew. He even managed to make a deal with a high-ranking official at the ministry of defense, Théoneste Bagosora. Bagosora agreed to keep the Hôtel des Mille Collines open if Ruseabagina kept another government-occupied hotel up and running (via the New York Times).

At the fatal moment when a group of militiamen finally broke into the building, a powerful local military man, General Augustin Bizimungu, told the intruders that anybody committing violence at the hotel would be killed. Bizimungu, who has since been convicted for his role in the genocide, had shown up at the hotel's on-site bar (via The Guardian). Rusesabagina spent time drinking with Bizimingu — a ploy he claims kept the ferocious general on his side when it mattered most.

The hotel becomes a safe house

As word got out about the hotel it quickly became packed with desperate refugees. One New York Times journalist who visited the Hôtel des Mille Collines described the overcrowded conditions when he got there, stating that at least 500 people were crammed into the building already on the 12th of April, less than a week after the massacres began. Together with the sheltering Tutsis, he witnessed men with blood-stained machetes walking past the windows outside.

Things got tough as the hotel became more and more crowded and conditions deteriorated. Desperate for food and drink, the group drank water rationed from the hotel swimming pool (via The Seattle Times). A failing generator took out the group's lights and electricity, and one extremely stressed expectant mother was forced to give birth in a back room (via The New York Times). Crammed in together, guests cooked on open wood fires on the floor. The hotel's phone line was also eventually cut, forcing Ruesabagina to use a lone fax machine to contact the outside world.

After 11 agonizing weeks of living in grim conditions, the Rwandan Patriotic Front arrived with U.N. backup. Over 1,200 guests were finally evacuated from the building and spirited away to a refugee camp.

Was Paul Rusesabagina really a hero?

Ten years after the Hôtel des Mille Collines was evacuated, Paul Rusesabagina's version of events was transformed into the critically acclaimed Hollywood blockbuster "Hotel Rwanda." The movie would nab Don Cheadle an Oscar nomination for his performance as Rusesabagina, and Cheadle's performance would shoot Rusasabagina to fame (via The Guardian).

Rusesabagina, who had been working as a taxi driver in Belgium, went from an obscure good samaritan to a celebrated hero seemingly overnight. He was employed to do speaking engagements abroad, and he even won the U.S. freedom medal, the highest honor that can be given to a civilian (via the BBC). However, the validity of his hero status is still up for debate.

According to Foreign Policy magazine, not long after the movie was produced, one of the hotel survivors wrote a damning book on the subject, entitled "Inside the Hotel Rwanda." According to this account, Rusesabagina simply used the disaster to extort money from his guests and he even passed the names and room numbers of the vulnerable occupants to local Hutu Power radio stations. A number of other guests have made similar claims. One survivor has stated that his friend was forced to sign an IOU in return for their stay, while another claimed that the manager starved his guests when they had no money to give him.

An alternative version of events

The survivors weren't the only people who objected to the story Paul Rusesabagina told. Although Rusesabagina has damned the U.N. in interviews, U.N. observers claim that there was a considerable U.N. presence at the hotel — a presence that Rusebagina himself tried to disperse (via The Guardian). The Belgian owned-building had also come to the attention of the Western media, which may be one of the real reasons its occupants were spared by prominent members of the regime.

Some witnesses and journalists have named U.N. troops working under the watchful eyes of Canadian General Romeo Dallaire, as the true heroes in the Hotel saga. For example, according to "Inside Hotel Rwanda" it was General Dallaire who talked General Augustin Bizimungu into safeguarding the hotel's occupants, not Rusesabagina (via the East African). Speaking with the press, General Dallaire himself has expressed outrage at the narrative promoted by "Hotel Rwanda," stressing that it was his skeleton crew of peacekeepers that saved the hotel guests (via Foreign Affairs). His story has also been corroborated by the reports of a British journalist, who stated that Tunisian U.N. troops were at the hotel warding off militia.

Although Rusesabagina has sold himself as a man who could talk to both sides, seen from a different angle his connection to the Hutu elite, and his frequent drinks with them seem quite sinister. Far from being a hero, U.N. observers claim that thanks to Rusesabagina they were forced to change the hotel room numbers to keep the guests safe.

Praised in the West, damned in Rwanda

Who is really telling the truth about the infamous hotel? Although the witness testimony is pretty damning, Paul Rusesabagina has argued that he has been smeared in the press by Rwanda's new regime (via Reuters). The current president of Rwanda, Paul Kagame, came to power when he helped stop the genocide in 1994. He has held power ever since, becoming the country's president in 2000 (via Vox). Kagame is a Tutsi, and some argue he has repaid the Hutus by introducing a discriminatory government of his own. Under his rule, countless journalists and opposition leaders have mysteriously disappeared. After enjoying a warm grace period with the West, he has been increasingly scrutinized by concerned observers and human rights groups (via DW).

Whatever you think of Rusesabagina, he has, to his credit, pointed out some of the disturbing aspects of the Tutsi president's new regime — warning that the violence has continued and that another genocide is possible. In response, the Rwandan press and the president himself have launched a series of damning critiques of Rusesabagina — summoning up willing volunteers to challenge his version of events.

Although he has often been celebrated in the West, at home Rusesabagina has been called a con artist, a genocide-revisionist, and a man who has made his fortunes from the misery of others.

Hero or terrorist?

A New York Times investigation into Paul Rusesabagina in 2021 turned up more disgruntled survivors willing to condemn the legendary hotel manager. One of the hotel workers went so far as to claim that Rusesabagina was not only not a hero, but that his brush with stardom has changed him for the worse, igniting in him a delusional ambition to become president of Rwanda.

After leaving Rwanda for Belgium in 1996, he became heavily involved in politics from afar, becoming president of the Rwandan opposition party, the MRCD (via the BBC). Rusesabagina's speeches and political maneuvering did not go unchallenged, and he was eventually forced to move to the U.S. after being repeatedly targeted by Kagame's agents.

While Rusesabagina was being harassed, inconvenienced, and even burgled, his own politics became increasingly radical. In 2018, Rusesabagina publically expressed his support for the FLN on YouTube — a dangerous paramilitary group made up of Rwandan fighters in Burundi and the Congo. The group has been widely condemned for killing innocent people in Rwanda, and Rusebagina's public endorsement of them completed his fall from grace, both in Rwanda and abroad.

Paul Rusesabagina is jailed

In an attempt to resolve the issue once and for all, Rwanda's National Commission for the Fight against Genocide published a report that trashed Paul Rusesabagina's story in May 2020 (via the New York Times). The introduction to the report offers another alternative explanation:

"According to testimony by the survivors, Rusesabagina did not play any role in their survival, instead a combination of factors including the intervention by United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR), protection by the French troops since the hotel housed the French army communication unit, and there's pressure from Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF) against the government forces."

The 96-page document goes on to argue that Rwandan forces were nervous about touching the hotel due to a notable French presence there (pg 63). As a result, they designated it a specially protected zone (pg 84). Although the report made use of extensive witness statements, some critics still believe that anti-Rusesabagina witnesses are Kagame stooges.

A few months after the damning document was compiled, Rusesabagina was finally arrested in Rwanda. In August 2020, Rusesabagina stepped onto a plane he thought was going to Burundi, only to discover government agents had taken him to Kigali. Authorities accused Rusesabagina of funding terrorism and committing murder and in September 2021 he was sentenced to 25 years on terrorism charges (via CNN). Today the truth about the besieged hotel remains as murky as ever, but in Rwanda at least Rusesabagina is no hero.