The Mysterious 1961 Death Of The Second Secretary-General Of The United Nations

Was former U.N. Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjörd murdered for defying the West? Although it sounds like a hogwash conspiracy theory, both leading journalists and U.N. investigators have argued that the sudden death of the U.N. official was deeply suspicious.

Hammarskjörd died in a plane crash in what was then called the Republic of the Congo in 1961. The first official investigations into his demise concluded that it was an accident. However, troubling witness testimony and some shocking confessions have cast a dark cloud over the incident. Hammarskjörd's work leading up to his death put him at odds with some of the most powerful people in the world; since the crash, accusations have been launched at the British government, the U.S. government, the Belgian government, and a major mining cooperation, among others (via Vice). Many people had strong reasons to dislike Hammarskjörd — but does that really mean they might have killed him?

A multitude of investigations stretching back more than 50 years have revealed a murky world of vested interests, Cold War paranoia, and international espionage. The jury is still out as to what exactly happened — but key pieces of the puzzle suggest some very dark conclusions.

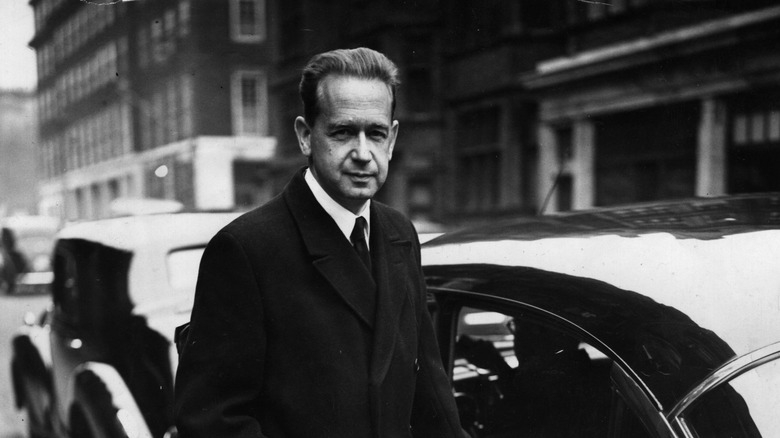

Who Was Dag Hammarskjörd?

Renowned diplomat and onetime politician Dag Hammarskjörd was put in charge of the United Nations in 1953, when the organization was still very young (via the U.N.). Hammarskjörd was a Swedish national, and the son of a Swedish prime minister, and many commentators have noted that he shared his father's strong moral compass and humanitarian convictions (via the New European).

Perhaps because of his early death, Hammarskjörd has often been held up as a near saint in recent times — but the praise he receives is not all hot air. Today many people regard the U.N. as a completely toothless organization but in the 1950s, Hammarskjörd worked hard to create an effective and truly neutral peacekeeping body. His version of the United Nations really did intervene in global politics when it was needed (via The Conversation). On his watch, the U.N. successfully rescued 15 American airmen from Chinese captivity and did a great deal of negotiating over the Arab-Israeli conflict. More controversially, he also interfered in the Suez Crisis and helped to force the U.S. and the U.K. to withdraw from Jordan and Lebanon.

The conspiratorily-minded believe he may have been too good at his job, setting himself up as a marked man. Hammarskjörd didn't give a darn about Western interests, only about peace and democracy.

Hammarskjöld's controversial work

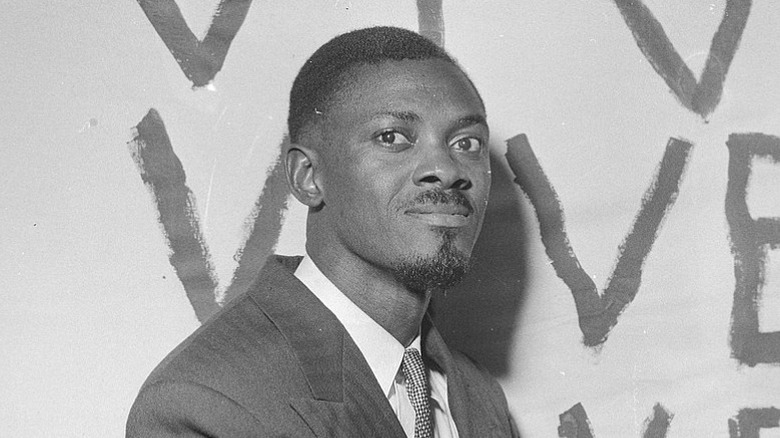

Dag Hammarskjöld was secretary-general at a difficult time in world history when many countries, especially in Africa, were being decolonized. This included the Belgian Congo, which was granted independence in 1960 (via U.S. State Department). Although a new democratic president, Patrice Lumumba, was elected in the Republic of the Congo (now called the Democratic Republic of the Congo) that year, independence did not go as planned. The country immediately dissolved into chaos, during which Belgian nationals were attacked, the new Congolese army became uncontrollable, and Belgian soldiers were deployed to keep order.

During the crisis, successionist forces led by Moise Tshombe in Congo's southern Katanga region tried to break away to form an independent state (via History). Hammarskjöld's U.N. continued to support a unified, democratic Congo despite the difficulties, sending peacekeepers to hold the country together.

The U.S., the U.K., and Belgium, on the other hand, suddenly decided to back Tshombe's rebels in Katanga (via the BBC). The situation had been complicated by the fact that Soviet forces had entered the Congo during the uproar — Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba had petitioned the USSR for help. Despite a jumpy U.S. government, U.N. troops attacked the separatists, throwing their support behind Lumumba.

Mining interests in the Republic of the Congo

Dag Hammarskjörd's interference in Katanga was no joke to the Western powers working in the region. The area is rich in various minerals, such as copper, cobalt, diamonds, and, most importantly — uranium (via the Journal of Modern African Studies). During WWII, the U.S. took control of the mines in Katanga and they went to great lengths to keep both the Nazis and the Soviet Union from touching them (via The Conversation). The material mined there went on to produce the atomic bomb that flattened Hiroshima. Given the danger, a Soviet-backed Republic of the Congo was just not an option.

On the other hand, the rising uncertainty also worried the Belgian mining company working in Katanga, Union Minière (via Vice). The Congo was one of the most profitable colonies in Africa, and despite pledges to de-colonize the region, Europeans had a strong interest in digging their claws in. When trouble exploded across the country, the mining executives went so far as to get involved in politics, backing the successionists in Katanga, and providing Tshombe with money for weapons.

Nevertheless, Tshombe's forces still had to contend with Hammarskjörd and U.N. and around 19,000 peacekeeping troops were deployed over the next four years to prevent the conflict from escalating. In public, the U.N. launched a damning attack on the Belgians for interfering in the country. It was amid this tense atmosphere that Hammarskjöld set off to speak with Tshombe personally — but he never arrived. His plane crashed outside the city of Ndola in September 1961.

The suspicious crash

Dag Hammarskjöld's plane was brought down in what was the British protectorate of North Rhodesia (now Zambia), on the border of the Republic of the Congo (via History). The circumstances surrounding the crash are more than a little suspicious; the evidence seems to suggest that the plane was brought down deliberately by gunfire. Marks that looked distinctly like bullet holes were found in the fuselage, and there was no evidence of anything mechanically wrong with the plane (via the Hammarskjöld Commission).

The one person who survived the crash, security officer Harold Julien, told authorities that he saw an explosion as well as sparks in the sky before the plane crashed. Unfortunately, Julien died of his injuries six days later and could not be questioned further.

Many witnesses on the ground have corroborated Julien's story, describing either gunfire or an explosion during the plane's descent. According to a 2011 investigation undertaken by The Guardian, many charcoal makers working in the Ndola forest at the time claim to have seen a second aircraft shooting at the plane. These witnesses were never questioned at the time of the crash. Curiously, when Hammarskjörd's body was finally found, he supposedly had an ace of spades playing card (an omen of death) tucked into his collar.

Although plenty of people saw the plane hit the ground, the British high command did not react right away. The British Commissioner at Ndola made no effort to investigate when Hammarskjöld did not turn up at the airport, simply stating he must have changed course.

The initial investigation

When the crash was first investigated it was written off as an accident. The police insisted that the sole survivor's witness testimony should be dismissed as mindless rambling on the grounds that he was disoriented by the ordeal (via the London Review of Books).

In early 1962, a special commission organized by British-run Rhodesia came to the conclusion that the crash was due to a pilot error, and that the craft had probably come in too low in preparation for landing (via the Hammarskjöld Commission). Two separate U.N. inquiries were also conducted in 1962, but they provided no definitive answers and were forced to conclude that the wreckage was so badly burned it was difficult for investigators to prove anything one way or the other. Unfortunately, the U.N.'s early investigations used the Rhodesian commission's findings as its starting point — but this first inquiry had simply dismissed almost all of the witness testimony as unreliable — including the words of the survivor Harold Julien.

Unsurprisingly, these early investigations did nothing to deter suspicion, and many people remained convinced that Dag Hammarskjöld had been murdered; not least because two days after the crash former President Harry Truman suggested as much. Speaking to the press about the crash Truman stated, "[Hammarskjöld] was on the point of getting something done when they killed him. Notice that I said 'when they killed him'" (via The Guardian). Since the '60s countless people have attempted to right the wrongs of the initial investigations.

An NSA agent claims the U.S. was involved

If the crash was no accident, who might have killed the meddling Swede? Years after the event, an informant came forward with claims that the U.S. government was one of the parties involved in a plot to kill the secretary-general (via CBC News).

Charles Southall, an NSA agent who worked in Cyprus at the time of the incident, claimed that one of his colleagues told him to come back to work that evening because "something interesting is going to happen." Southall went on to say that he was then shown a video of a pilot firing at the DC6 aircraft. On the recording, the pilot supposedly gave verbal confirmation that he had successfully downed the plane.

Speaking with journalist Susan Williams, who wrote a popular book on the crash, Southall said of the CIA, "at least they paid for the bullet" (via The Financial Times). His testimony was later used as evidence by a U.N. commission, who noted that if his story was accurate it suggested that the crash was a pre-planned assassination (via the Hammarskjöld Commission).

The Operation Celeste controversy

In 1998, a paramilitary group from South Africa was also added to the growing list of suspects (via The New York Times). A set of documents from the apartheid era were uncovered that described a plan to murder Dag Hammarskjöld. The plot, codenamed "Operation Celeste," was supposedly the work of the curiously-named South African Institute of Maritime Research, a paramilitary organization. The group had the support of the U.K. and the U.S., as well as the Belgian mining outfit working in the area.

The documents in question describe a covert operation to plant explosives on the plane and they include a set of messages from the conspirators (via the Hammarskjöld Commission). One of the notes reads: " ... it is felt that Hammarskjöld should be removed. Allen Dulles [head of the CIA] agrees and has promised full cooperation from his people."

The validity of the documents has never really been established, and the British government later responded to the incident by claiming that the documents were fakes, created by the USSR (via History).

The murderer may have confessed

More concrete evidence of a potential plot against Dag Hammarskjöld emerged in 2014 when some U.S. documents from the time were finally declassified (via The Guardian). It was discovered that on the day of the crash, the U.S. ambassador to the Republic of the Congo sent a message to Washington in which he blamed a Belgian mercenary for shooting the craft down. In the cable, the ambassador noted that the pilot had been hampering U.N. operations in the region. The Belgian pilot, Jan van Risseghem, had trained with the RAF in Britain during World War II and he later sold his skills as a mercenary in the Congo (via The Guardian).

An investigation into Risseghem's flight logs appeared to exonerate him — according to his own records, he wasn't even flying at the time the crash occurred. However, a documentary investigation into the pilot's logbooks revealed that they were filled with fake names and were probably forgeries. A U.N. report published in 2017 also established that there was conflicting evidence about Risseghem's whereabouts at the time of the crash. The report states that Hammarskjöld himself had actually complained about the renegade pilot and his activities before his death.

After he died in 2007, one of Risseghem's friends alleged that the mercenary had confessed to killing the secretary-general. When he pressed Risseghem on the matter the pilot supposedly replied, "Well, in life, sometimes you have to do things that you don't want to do ... "

Was the plane accidentally shot down?

A popular alternative theory regarding the death of the secretary-general is that the plane was shot down by accident in a clandestine operation gone horribly wrong. This theory comes from two former U.N. workers, Conor Cruise O'Brien and George Ivan Smith, who wrote a letter to The Guardian newspaper in 1992 (via BBC). Smith, in particular, was close to the secretary-general, and once worked as Dag Hammarskjöld's personal assistant (via The London Review of Books).

The O'Brien-Smith letter put forward a theory that a mercenary caused the plane to crash by accident when he fired a warning shot in an attempt to divert the craft. Smith's investigation into the affair led him to conclude that a group of European industrialists with business interests in the Republic of the Congo had been attempting to kidnap Hammarskjöld in order to talk some sense into him about Kantaga (via the Hammarskjöld Commission). Unfortunately, this theory relies on the evidence of some shadowy informants, including a Belgian pilot called Beukels, who supposedly confessed to the killing. His story was recorded secondhand by a French diplomat who passed the story on to Smith.

The U.N. report, released in 2013, noted that while the accusations were just hearsay, the details given by the mysterious pilot did line up with some of the other witness testimony. The failed-kidnapping theory has little supporting evidence but remains popular today.

Britain was accused of frustrating a new investigation

By the 2010s, with an overwhelming amount of new evidence available, then-U.N. Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon ordered a new series of investigations into the crash (via Vice). However, the investigators struggled to obtain some of the key files they needed to complete the inquiry.

The U.K., in particular, was deemed wholly uncooperative during the search; although the British government holds documents on the crash, they refused to release uncensored versions. The U.N. was particularly interested in obtaining a report written by MI6 agent Neil Ritchie, who helped orchestrate a meeting between Dag Hammarskjöld and the rebels. While the British Foreign Office insisted that any secrecy was simply a security measure, it has done nothing to calm the nerves of conspiracy theorists.

Britain took a full 15 months to respond to the initial request and then never came up with the goods (via The Guardian). The U.S., Belgium, and South Africa were all also accused by the U.N. of being difficult and secretive.

The 2019 investigation

The U.N. published its most recent verdict on the crash in 2019, after a 3-year investigation (via The New York Times). Perhaps the most damning conclusion from the new report was that the early British-Rhodesian investigators seemed resolutely determined to conclude that the crash was an accident.

The report notes that although at least six people told the initial inquiry in 1961 that they had seen a second plane in the sky, the Rhodesian commission " ... was generally critical of those witnesses in a manner that was not objective, which may have been related to its pre-established bias" (via the U.N.). The new U.N. investigation was also able to find many more witnesses who claimed to have seen a second aircraft but were not questioned at the time.

Although the U.N. panel was unable to come up with a definitive explanation for the crash, they ruled that an attack on the plane was still plausible. The 95-page report recommended that the investigation continue and that uncooperative member states be pushed once again to release relevant documents.

An enduring mystery

Some details about the crash that were dismissed by the U.N. continue to intrigue the public today (via Vice). For example, it is often reported that some of the bodies found at the crash site were found peppered with bullets — although the U.N. ruled in 2013 the wounds were most likely discharges from superheated ammunition stored on the plane (via the Hammarskjöld Commission). Others are convinced that photos from the crash were retouched to hide a bullet hole found in Dag Hammarskjöld's forehead (via the BBC). The official inquiry was doubtful that the photos had been tampered with, concluding the spots were likely to be pressure marks.

The potential motives for a possible murder are also the subject of endless speculation. For those who believe it was murder, Belgium, the U.K., the U.S., South Africa, and the Union Minière mining cooperation remain the most commonly named culprits. Whether you put it down to Cold War politics or simple profit motive, rumors of a murderous plot are likely to circulate for years to come.