The Largest Chemical Weapons Attack On Civilians Explained

In the early 2000s, the United States government claimed that Iraq had weapons of mass destruction in order to justify the invasion of Iraq and the removal of Saddam Hussein from power. These claims turned out to be untrue, but in making this claim, the chemical attack on Kurdish civilians in Halabja was repeatedly brought up as an example of how necessary the invasion was. The ironic thing was that when the massacre actually occurred in 1988, the United States was indifferent to the news and continued to support the dictator who was responsible.

The 1988 chemical attack on the Kurdish civilians in Halabja, Iraq, is one of the most horrific examples of genocide and ethnic cleansing in history. In addition to being the largest chemical weapons attack against a civilian population, the injuries and health effects caused by the toxic gas transcend generations as children continue to be born with congenital birth defects. But as of 2023, most of the international community doesn't formally recognize the Kurdish genocide.

The Kurdish Genocide

In 1988, between 50,000 and 200,000 Kurdish people were murdered during the Kurdish genocide in Iraq. Also known as the Anfal campaign, the Kurdish genocide lasted from February to September 1988. But in just eight months, PBS writes that the ethnic cleansing launched by President Saddam Hussein led to the destruction of thousands of villages, largely through the use of chemical bombs.

After Kurdish villages were inundated with chemical bombs, Iraqi ground troops would sweep through the villages and destroy everything. Human Rights Watch writes that in some areas, the army would even pass through again months later just to obliterate any remaining trace of human life.

Chemical bombs were repeatedly used during the Kurdish Genocide, but the attack on the city of Halabja in March 1988 is notable for being, as of 2023, the largest chemical weapons attack against a civilian population to date, according to the Federation of American Scientists. The Halabja massacre wasn't technically part of the Anfal campaign, but it's incredibly demonstrative of the Iraqi government's genocidal intent against the Kurdish people.

Dropping chemical bombs

On March 16, 1988, the Iraqi army attacked Halabja, a Kurdish city in Iraq with a population of up to 80,000 people. The Anfal campaign had already begun, but the Federation of American Scientists writes that the attack on Halabja was considered to be an additional retributive attack in response to the presence of the Kurdish Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and Iranian revolutionary guards in the city. In "The Modern History of Iraq," Phebe Marr notes that Halabja's location near the Darbandikhan Dam was also strategically significant.

Bianet reports that initially, the Iraqi air force attacked first, dropping conventional bombs and rockets onto the city. The ground troops came in afterward, destroying as many windows as possible, and as soon as they cleared out of the city, the air force moved in. The planes circled overhead, dropping chemical bombs on Halabja's civilian population, according to the Institut Kurde de Paris. And Al Jazeera reports that with many windows and doors broken, the yellow smoke, which was heavier than air, easily made its way into basements and shelters where people were hiding.

The smell of apples

As soon as the chemical bombs were released into Halabja, the city was struck by the smell of apples, but as the sweet scent swept through the city, it became clear that it wasn't coming from any actual fruit. This was the smell of a gas attack. According to "One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare," some people also recall the smell of garlic, rotten eggs, trash, and bananas permeating through the city, as well as oranges and almonds.

But the smell of apples may have been the strongest because it's the smell that has continued to resonate in the memories of the Kurdish people who survived the massacre. Hosmand Morad Mohammed, who was in Halabja during the attack, told Middle East Eye how everyone who lived through the massacre continues to negatively associate apples with the death and destruction they witnessed that day: "When we talk about apples we remember the nightmare ... Today, we can eat and even smell apples. But it is difficult. We just don't like it." Aras-Abid Akram, head of the cultural center of Halabja, also notes that "the smell [of apples] will always remind us of the chemical attack of 1988," per The Irish Times.

Chemical bombs were dropped and released for almost an hour as people tried to escape the noxious white-yellow gas. Many quickly noticed an irritation in their eyes and on their skin and started struggling to breathe, but the chemical bombs were about to do a great deal more damage.

Dropping dead in the streets

People started dropping dead in the streets from the chemical bombs within minutes. The Irish Times reports that some people didn't even make it past their front door in their attempts to escape the toxic gasses filling their homes. Many vomited immediately from the gas and died just a few minutes later. Even some who managed to flee Halabja didn't escape the effects of the gas and died hours after the attack, writes "One Hundred Years of Chemical Warfare."

It didn't take long for the streets of Halabja to become littered with the bodies of dead people. Many simply dropped dead as they tried to escape, while others died huddled inside their homes. Mahsume Gul, who survived the chemical attack, recalled, "I was seeing dead bodies everywhere I looked [...] I went out to the streets which were full with corpses and people fighting for their life," per ANF News.

The chemical bombs also contaminated the water in the area, and anyone who drank the water or used the water to wash themselves ended up with severe chemical burns. According to Middle East Eye, one of the survivors of the Halabja massacre, Garda Hussein, used the contaminated water, and as a result, her skin quickly burned and fell off. Although she and her family were able to eventually get medical attention after the massacre, Hussein ended up with long-term nerve and brain damage from the chemical attack.

Dying of laughter

One of the most disturbing ways that people died during the Halabja massacre was from laughter. As some people started to feel the effects of the toxic gas, they would start laughing uncontrollably until they finally collapsed, writes Majalla. And unfortunately, this wouldn't always be a quick death. Those who managed to survive watched as their loved ones laughed themselves hysterically to death, sometimes ripping off their clothes in the process, in a moment utterly devoid of comedy. According to the BBC, the massacre became known as "Bloody Friday."

The fact that some people died laughing, some simply dropped dead, and others vomited green in their final moments was due to the fact that the chemical gas was a lethal cocktail of numerous chemical and nerve agents, which included mustard gas, sarin, tabun, and VX. Animals were also affected by the lethal gas cocktail. Livestock and wild birds in the area dropped dead as well and their bodies clearly bore the effects of the chemical attack. The New Yorker writes that even the leaves started falling off the trees.

Human Rights Watch reports that up to 5,000 Kurdish people, all of whom were civilians, died in the immediate aftermath of the chemical bombing of Halabja. Additionally, between 7,000 and 10,000 people were injured by the chemical attack, and the massacre would claim many more victims over the following decades.

Fleeing the gas chamber

As soon as people realized their city was turning into a gas chamber, those who were physically able to began to flee. Nasreen Abdel Qadir Muhammad tried to run with her family as fast as they could in the opposite direction of the wind, but many of them could barely walk. "The children couldn't walk, they were so sick. They were exhausted from throwing up. We carried them in our arms," she said, per The New Yorker.

Everyone tried to get out of the city and towards high ground, but many found their eyesight failing as they fled. For some, their eyesight would eventually return. Others weren't as lucky.

According to "Ghosts of Halabja" by Michael J. Kelly, while Kurdish people fled the toxic town, Iraqi government troops reportedly went into Halabja wearing chem-bio suits. But they weren't there to help. Instead, they were there to monitor the effects of the gas and how many people died.

Journalists spread the news

Iranian journalists who were already in the region soon discovered the aftermath of the gruesome massacre, having noticed the military aircraft and bombing in the area. But the Tehran Peace Museum writes that only upon reaching the center of Halabja did Iranian journalists realize that a chemical attack had occurred.

Although the journalists in the area tried to help the Kurdish people who were still alive and tried to get as many as they could to medical attention, journalist Saeid Sadeghi states that it took longer for Iranian soldiers to arrive and help evacuate some of the survivors. Kaveh Golestan, another journalist at Halabja, described the city as "life frozen. Life had stopped, like watching a film and suddenly it hangs on one frame. It was a new kind of death to me," per "Understanding Shadows" by Michael Quilligan.

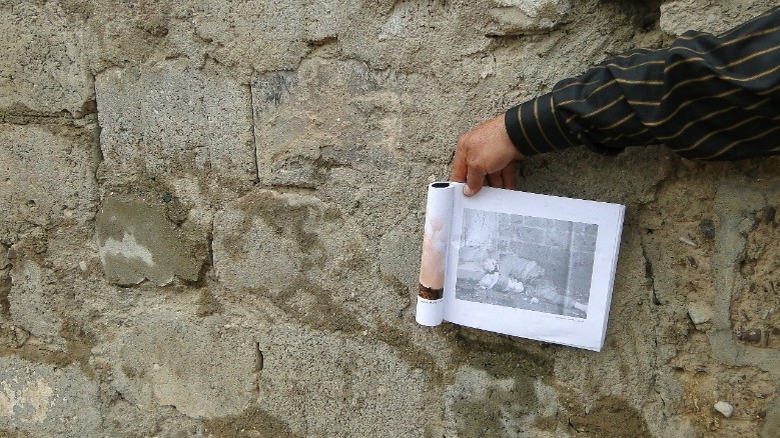

However, journalist Ramazan Öztürk, who photographed the aftermath of the massacre, notes in an interview with Rabîa Çetîn that at the time, many of the newspapers, foreign and local, didn't give the story much thought, and many limited the coverage to brief comments regarding the deaths of Kurdish people in a chemical attack. And according to "Late-breaking Foreign Policy" by Warren P. Strobel, American news network producers also filtered out some of the evidence of the massacre that was shown because "some of the pictures were horrific. You would just not put them on."

Iraqi and international denial

The Ba'ath regime had not anticipated that news of the massacre would actually get out, so there was soon denial on both a domestic and international level. According to the Middle East Contemporary Survey, the Iraqi government touted the support of two pro-government Kurdish groups in an attempt to demonstrate their good relations with the Iraqi Kurdish people.

CBC reports that by the end of March 1988, the United States government suggested that Iran was responsible for the chemical attack, and the Iraqi government was more than happy to accordingly assign blame. Some Kurdish survivors were even forced to lie to TV crews and say that Iran was responsible, per "A Poisonous Affair" by Joost R. Hiltermann. This denial of Iraqi responsibility was often repeated by state governments, journalists, and independent scholars. Even Edward Said wrote in the London Review of Books in 1991 that "The claim that Iraq gassed its own citizens has often been repeated. At best, this is uncertain."

But before long, representatives of the Iraqi government were admitting the use of chemical weapons, per The Washington Post. Despite these acknowledgments and even after continued chemical attacks, the United States government still refused to investigate Iraq's use of chemical weapons against its own civilians, according to "The United States, Iraq, and the Kurds" by Mohammed Shareef. Shareef notes that this was because after the 1979 Iranian Revolution, the United States sought to maintain Iraq as an ally against Iran.

Destroying the evidence

Any evidence of the massacre in Halabja was eventually destroyed by the Iraqi army. The Institut Kurde de Paris writes that in July 1988, the Iraqi army returned to Halabja to completely raze what was left of the city. By October 1988, the Ba'ath regime announced that Halabja was to be rebuilt, one month after the Iraqi government completed their eight genocidal Anfal campaigns, per "Middle East Contemporary Survey." This rebuilding was also largely a cover to completely wipe away any memory of the massacre. According to "Disciplinary Spaces," edited by Andrea Fischer-Tahir and Sophie Wagenhofer, those who managed to survive the massacre and remained in the area were forcibly displaced and resettled.

Despite all of these attempts by the Ba'ath regime to destroy the evidence of their ethnic cleansing, mustard gas was still discovered in the soil samples from the area. But unfortunately, according to "Echos of Genocide," it would still take several years for the international community to acknowledge the Iraqi regime's genocidal crimes.

International response

Doctors Without Borders sent a team to Halabja a week after the massacre. According to Science Magazine, the team only stayed for five days, but during that time they made an estimation of the dead, took samples from soil, plants, animals, and people, and interviewed refugees and first responders. But despite sending their report to the U.N secretary-general, "the reaction of the Western world wasn't so heavy."

According to "Massacres and Morality" by Alex J. Bellamy, the United States government also had conclusive evidence that the Iraqi government was using chemical weapons against its own civilians and undertaking the ethnic cleansing of the Kurdish people. But the State Department continued to publicly call reports of massacres Kurdish propaganda. According to The New York Times, the State Department even ordered some diplomats to push the blame onto Iran.

The United States wouldn't turn on President Saddam Hussein until 1990, when the Iraqi army invaded Kuwait. But even then, the horrors of Halabja weren't really brought up. It wouldn't be for another decade, in 2002 and 2003, when the United States government started bringing up the Halabja massacre in order to justify their invasion of Iraq, per The Washington Post.

Lingering medical consequences

Over 30 years later, survivors of the Halabja massacre still have lingering health effects due to the chemical attack. In addition to experiencing PTSD, anxiety, and depression, the University of Gothenburg has found that many of the Kurdish people who survived the massacre suffer from respiratory conditions and eye problems. And according to International Business Times, the increased rates of fertility, miscarriage, and birth defects are also a result of the chemical attack.

There is also an increased risk of cancer among the survivors of the chemical attack. Geneticist Christine Gosden has stated that "I've seen Europe's worst cancers, but, believe me, I have never seen cancers like the ones I saw in Kurdistan," per The New Yorker. And young children, unfortunately, aren't exempt from this. The high cancer rates and congenital defects reflect how the Halabja massacre and attack on the Kurdish people still have not ended.

According to France24, as of 2021, there were up to 500 people who survived the Halabja massacre that were seriously disabled by the attack. But neither the Iraqi government nor the Kurdistan Region government has a program in place to offer care to the survivors.

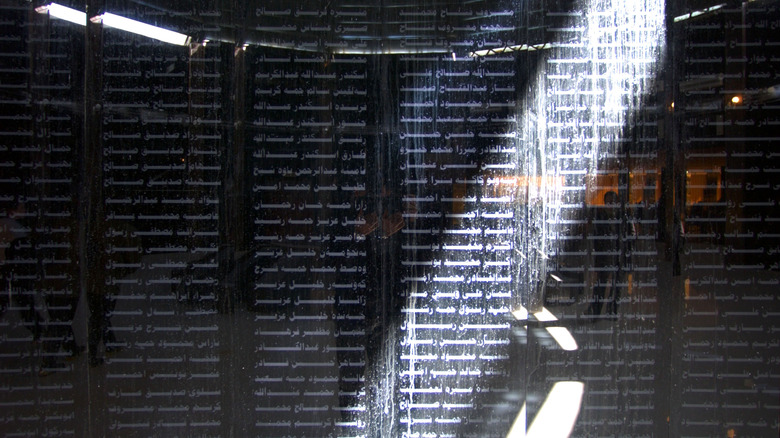

Legacy of the Halabja massacre

For some of the survivors of the Halabja massacre and their families, the wound remains very much open. According to France24, many children went missing during the attack and because some were taken to Iran for treatment, they were separated from their families who continue to look for them. It's estimated that up to 150 people went missing as children.

Although Ali Hassan al-Majid, cousin of President Saddam Hussein and the general who ordered the attack on Halabja, was executed in 2006, this was a small consolation prize for many survivors who lost their families.

In March 2018, 5,500 survivors of the Halabja massacre and their relatives filed a lawsuit in Halabja civil court against the over two dozen European companies and co-conspirators that facilitated then-President Saddam Hussein's chemical attacks, reports Kurdistan24. And for even those who aren't listed as plaintiffs, a legal win would be a significant symbolic victory. As of October 2022, The Tennessean writes that the trial continues to be underway. However, none of the defendants have shown up to the trial.