The Tethys Sea: The Story Of The Ocean That Covered Ancient Earth

From our perspective, Earth looks and feels static and solid, but our planet is constantly changing. It's just difficult to notice over a single human lifetime, because geological timescales are breathtakingly vast. The most dramatic changes on Earth's surface are caused by tectonic plates, huge rafts of solid rock which make up the planet's crust. Over time, gradually but unstoppably, they jostle and grind against each other, causing earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Eventually, the motion of the tectonic plates even causes entire continents to change position as they slowly drift. Even though it's slight, with modern technology that drift can even be measured. As National Geographic notes, each year North America moves about an inch further away from Europe as the Atlantic Ocean gradually widens.

As the continents slowly shift their positions, so too do Earth's oceans. There's even an entire science, paleoceanography, dedicated to the study of long-lost seas from the distant past. Over the course of Earth's history, old oceans have closed up and new oceans have split open, radically changing the appearance of the entire planet. The oceans we know on the Earth today, Pacific and Atlantic, Indian and Southern, weren't always there. Millions of years ago, when dinosaurs still roamed the world, it would have been the Tethys Ocean that which looked out over — an ocean that existed on Earth for most of the history of life on land.

Pangea and Panthalassa

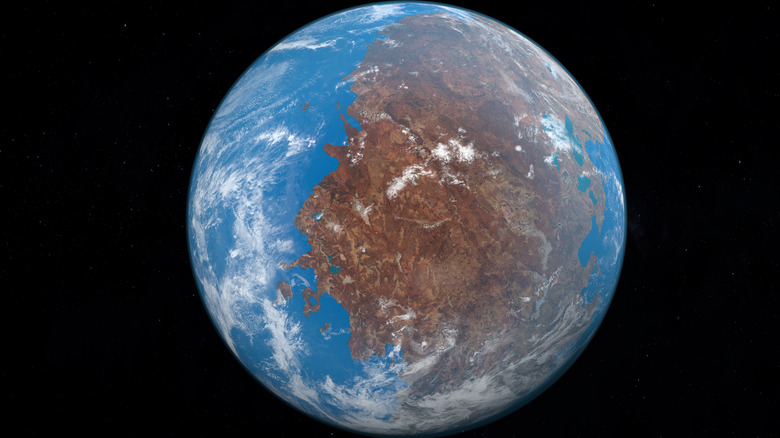

A few hundred million years ago, Earth would have been almost unrecognizable to human eyes. Where the world today has seven continents, this ancient Earth only had one. Pangea. A mighty supercontinent formed by all of the world's landmasses being mashed together through the motion of tectonic plates. With only one continent, the rest of Earth was covered by only one ocean: a vast expanse of water known as Panthalassa, one of the largest bodies of water Earth has ever known.

But Panthalassa would not last. As Earth's surface continued to shift and change, so land masses would change too. As parts of Panthalassa were sectioned off, new oceans began to form. According to a study published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, the vast Panthalassic Ocean was the ancient precursor to what is now the Pacific. But the Pacific as we know it today wouldn't exist for hundreds of millions of years to come, and Panthalassa would give birth to another ocean first. The lost Tethys Ocean.

The Paleo-Tethys Sea

As geologists have learned more about Earth's past, they've realized that rather than there being a single Tethys Ocean, this ancient body of water was formed gradually in a few different stages, and the first of these is known as the Paleo-Tethys Sea (or sometimes Paleo-Tethys Ocean). The great continent of Pangea was curved, roughly forming a gigantic C-shape, and over time, a small piece of Panthalassa started to become cut off as Earth's continents slowly shifted. Eventually, the Paleo-Tethys Sea formed as a kind of "pocket ocean," mostly enclosed by Pangea.

This happened staggeringly long ago in Earth's history. The Paleo-Tethys Sea's origins date back to the Devonian Period, roughly 420-360 million years ago. At the time, most life on Earth was still confined to the oceans. Animals were only just beginning to crawl out of the sea, and the first of them to do so were not our ancestors. As Big Think explains, the first animal to find its way onto land was likely a kind of ancient millipede, some 425 million years ago. It would be another 35 million years before the first vertebrate animals would begin to live on land. As these ancient creatures, which we would eventually evolve from, found their way onto ancient beaches, it may have been the Paleo-Tethys Sea which they hauled themselves out from.

The breakup of Pangea

A continent as big as Pangea could never last. Vast, and spanning multiple tectonic plates, it would eventually begin to split apart as Earth's crust continued to shift. Around 300 million years ago, the huge supercontinent began to split apart, and its fragments began their gradual journeys to become the continents we now recognize today. The first step was for Pangea to split in two, forming into a pair of continents known as Laurasia and Gondwana. The newly formed body of water between them would become the Tethys Ocean. But this newborn sea may also have had a hand in actively breaking up Pangea.

As Earth's tectonic plates bump together, sometimes one starts to slip underneath another, sinking below Earth's crust and slowly dissolving into the magma beneath. Regions where this happens are known as subduction zones, and it was likely this kind of motion that tore Pangea asunder. According to Science News, subduction zones like these would have likely caused tension on Earth's tectonic plates millions of years ago. As Earth's gravity pulled oceanic plates downwards further into the subduction zones at the edge of the Tethys Sea, it would have put immense strain on one specific part of Pangea — the region between what would eventually become Africa and North America. Eventually, this was likely what ripped the ancient supercontinent apart.

The Tethys Ocean

From our perspective, it's easy to think of an Ocean as a simple expanse of water. After all, most of us only ever see the surface of it. Oceans are often more complicated than this, however, and Tethys was no exception. As the book "Tethys Ocean" explains, the titular ocean, at its grandest, was actually a huge collection of ocean basins. Not one ocean, but a collection of oceans all joined together, covering a huge swathe of planet Earth.

The Tethys Ocean wasn't just continuous water though. There were likely a variety of lesser landmasses and volcanoes scattered across it. In particular, there were numerous small islands strewn around the Tethys Ocean, and some of them still exist today, although they're no longer islands. These ancient landmasses would eventually become parts of Italy, Anatolia, and the Iberian Peninsula. While the ancient Earth still looked vastly different from the way it does today, pieces of our modern world were already beginning to take shape.

Ancient coral reefs

All around the periphery of the Tethys Ocean were continental shelves, parts of Earth's continents submerged under shallow seas. In the balmy waters, these shelves would have been home to sprawling reef ecosystems, bristling with color and diversity. The Tethys Ocean was very likely full of corals.

Corals are an astonishingly ancient form of life. Paleontologists believe they first evolved over half a billion years ago, meaning that corals have been living in Earth's oceans for over 10% of the time our planet has even existed. However, these early corals weren't much like the ones we know today. Modern corals wouldn't evolve until much more recently, as a paper in Earth-Science Reviews explains, first appearing during the Triassic Period. As dinosaurs were roaming on land, these corals were flourishing in the shallow waters of the Tethys Ocean.

The creatures which lived in these ancient coral reefs would also have included creatures we know only from fossils. Ammonite shells are among the most famous and abundant fossils in the world, so common that they can be easily found on some beaches simply by splitting apart carefully chosen rocks. In life, ammonites were ocean-dwelling mollusks similar to nautiluses. Looking something like a cross between a squid and a garden snail, these ancient creatures lived throughout Earth's seas until they were wiped out by the same extinction event which killed off the dinosaurs. Before this, they may have been a common sight in the reefs of the Tethys Ocean.

Ancient islands

The motion of Earth's tectonic plates is often driven by volcanoes deep below the sea. Over time, their eruptions build up vast amounts of volcanic rock, until eventually, they form volcanic islands like Hawaii and Japan. With their rich volcanic soils, these islands tend to be full of nutrients that can drive verdant plant growth. Most volcanic islands in the world today are relatively young, having only existed for a few million years, but it's likely there were much older islands that have since sunk back below the waves. A study published in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B reports that the western Pacific Ocean is hiding some ancient volcanic hotspots which may be sunken islands. Dating back to 140 million years ago, these may have once been volcanic islands in the Tethys Ocean.

Other ancient islands are quite well studied. One is known as Hateg Island, a tiny piece of the ancient Earth that has long fascinated Palaeontologists. As a paper published in Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology explains, it was home to dwarf dinosaurs. The distinct environments of islands can cause animals to evolve in strange but predictable ways, sometimes growing to giant proportions like the Tortoises of the Galapagos, and other times becoming dwarfs. As well as animals, the ancient islands of the Tethys Ocean also contained lakes, and judging by the fossil record, those lakes were bristling with distinctive types of aquatic plants. Earth's islands, clearly, have always been biologically fascinating places.

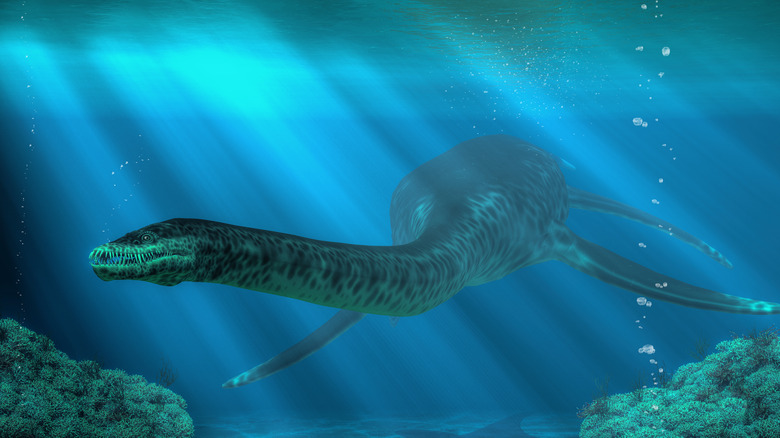

Here be monsters

When the Tethys Ocean spanned the globe, it was home to some true sea monsters. During the early 19th century, British paleontologist Mary Anning discovered the fossilized remains of an ichthyosaur, a creature that would become one of the best-known of Earth's ancient fauna. Per Live Science, ichthyosaurs first evolved around 250 million years ago and were among the largest creatures ever to swim through the seas. Apex predators of the Tethys ocean with long crocodile-like snouts filled with vicious teeth. They lived at the same time as dinosaurs but, despite their name, they were not actually dinosaurs themselves. Instead, they were part of their own distinct class of creatures, marine reptiles known as archosaurs. Looking strikingly like sharks and dolphins thanks to convergent evolution, these creatures would have ruled the Tethys Ocean, feasting on schools of ancient fish.

Another ancient beast of the Tethys Ocean is no less famous. The plesiosaur. These were an entire category of archosaur, first evolving around 215 million years ago. Plesiosaurs had a captivating appearance, with long necks, short tails, and sealion-like fins which they would have used to glide through the ancient seas. Like ichthyosaurs, they could also grow to be extremely large. One plesiosaur fossil, unearthed from the Norwegian archipelago of Svalbard, apparently had a head over 9 feet long. It may have had the most powerful bite of any animal ever to have lived.

The home of Earth's first whales

When the dinosaurs went extinct, much life in the oceans was also lost. While life on Earth recovered and rebuilt, the Tethys Ocean was beginning to close up. Earth was beginning to look more and more like the world we know today. But in the waters of the Tethys Ocean, one more famous aquatic creature was beginning to evolve. Whales. Per Smithsonian Magazine, the oldest ancestors of whales first began taking to the water around 53 million years ago, in the Tethys Ocean's final days.

Earth's first whale looked nothing like the immense sea animals in Earth's modern oceans. In fact, it was a land creature, known as pakicetus. A wolf-sized animal, it lived along the ancient shoreline of the Tethys Ocean, and rather than spending all of its life in the water it would swim for extended periods of time before returning to land. Pakicetus was likely very similar to the sea wolves which live on the Pacific coastline of modern-day Canada. In a few tens of million years, the Canadian sea wolves might evolve into something resembling a whale themselves.

It wouldn't be for several million more years until pakicetus would evolve into something more closely resembling a true whale. One of the earliest such creatures is known as Dorudon, an animal with fins but also with vestigial legs. However, by the time Dorudon evolved 40 million years ago, the Tethys Ocean was already gone.

The end of Tethys

By around 50 million years ago, Pangea was nothing more than a distant memory. Even Laurasia and Gondwana had broken into fragments. Pieces of what was once the southern continent of Gondwana drifted steadily northwards, colliding with what was now Eurasia. India, Arabia, and Apulia (a part of South Europe) steadily closed off all that remained of the once mighty Tethys Ocean, eventually sealing it off from the rest of Earth's oceans. By now, the world was dominated by modern bodies of water, like the Atlantic and Indian Oceans. After being present for several chapters of the history of life on Earth, the Tethys Ocean was finally no more.

But the landmasses didn't stop when they'd closed off the Tethys Ocean. As a conference paper from an American Geophysical Union Meeting explains, the colliding continents kept pushing together, building up immense pressure. The land itself began to crumple and buckle, pushing up the characteristic mountain ranges of Eurasia. Apulia's collision with Europe caused the formation of the Alps, while the immense force of India colliding with the rest of Asia caused the formation of the Himalayas, Earth's highest mountain range. The motion of these broken pieces of the ancient continent of Gondwana would build the Eurasia we know today while simultaneously sealing the fate of the Tethys Ocean.

The seafloor in the sky

In the highest mountains on planet Earth, traces of the long-lost ocean can be found hiding in ancient rocks. As The Hindu explains, the rocks of the Himalayas are rich with fossils of long-dead sea creatures. When India collided with Asia, the ancient sea beds of the Tethys Ocean were pushed up, rising from the depths where they once lay, high into the sky. The tallest and youngest of the Himalayan mountains are chock full of limestone, and the oceanic fossils trapped in the rocks betray their ancient origins as part of the Tethys Ocean.

The same is true of other mountain ranges in Eurasia too. Ocean fossils can also be found in the Alps, with the rocks of Switzerland containing ichthyosaur fossils that date back to the days of the Triassic Period. The deadliest predators of ancient seas are now entombed in rock, high above the oceans they once would have called home. Even though the Tethys Ocean is long gone, the continents which closed it off are still moving together even today. Per the USGS, the Himalayas are still growing taller bit by bit, rising higher by about one centimeter every year.

The ocean and the oilfields

Crude oil, as a fossil fuel, is made from the decayed remains of ancient living things — though it's a common misconception that oil comes from the remains of dinosaurs. Instead, per The New York Times, crude oil actually comes from the remains of ancient ocean microbes. Even today, a constant rain of organic matter falls steadily to the floor of the ocean. Known as marine snow, much of this is made up of dead plankton, drifting steadily downwards and slowly decaying at the bottom of the ocean. Over time, this thick sludge of decaying organic material, combined with the internal heat of the Earth, eventually forms into oil. Among the hydrocarbon chemicals found in crude oil, scientists have even found the remains of ancient chlorophyll, confirming its origins as long-dead plankton. The oilfields of Eurasia today are the last remains of the ancient microbes that the Tethys Ocean once teemed with.

This is why the Arabian Peninsula and surrounding areas are so abundant in oil, sandwiched between layers of sandstone and limestone. Like the oil itself, these rocks are formed from the floor of the long-lost Tethys Ocean. The Zagros Mountains of Iran were formed in much the same way as the Alps and the Himalayas, as Arabia collided with Eurasia, forcing Earth's crust into mountains. Being rich in minerals that once came from the depths of the Tethys Ocean is why these mountains are now abundant in crude oil and natural gas.

The last traces of Tethys

With its active plate tectonics, Earth has an unfortunate habit of devouring its own past. Much of Earth's ancient crust no longer exists, but there are still traces of the Tethys Ocean in the world's seas today. They can be found by those who know where to look. A study in Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B notes that deep beneath the Pacific Ocean lies some of the oldest ocean floors on Earth. A huge tract of land deep below the waves, this stretch of ancient seafloor dates back 167 million years. It may be below the Pacific today, but it once lay under the Tethys Ocean.

Even a few remains of the Tethys Ocean itself still exist in Europe. The most prominent is the Mediterranean Sea, while the Black Sea, Aral Sea, and Caspian Sea are also remaining fragments of what was once Earth's greatest ocean. However, the Mediterranean very nearly didn't survive. Per National Geographic, when Earth's plate tectonics closed off the Tethys Ocean, the Mediterranean was originally sealed off completely. For an age, the sea slowly dried out, turning into an arid basin of salt. Then the waters of the Atlantic broke through the Strait of Gibraltar, cataclysmically refilling the Mediterranean with alarming speed. The young Atlantic breathed life once again into the last remnant of Earth's forgotten ocean.