14 U.S. Presidents Who Didn't Survive 10 Years After The End Of Their Presidency

The myth that the American presidency prematurely ages the occupants of the office does seem to be just that — a myth. Aging isn't something that can be tracked by a test or a straightforward, linear assessment. Efforts to calculate life expectancy for a president, based on the statistics from their inauguration year, indicated a slightly elevated lifespan on average. The impression that the office accelerates aging, Professor S. Jay Olshansky told History, may just come down to their visibility compared to the average person.

Presidents have increasingly gone on to long and productive work outside of office, a trend perhaps most exemplified by Jimmy Carter and the Carter Center. But health, luck, and inclination haven't given all presidents such storied second careers. Some didn't have long to enjoy a quiet retirement, or any other kind for that matter. U.S. history has seen several former commanders-in-chief pass on within a decade of leaving the presidency.

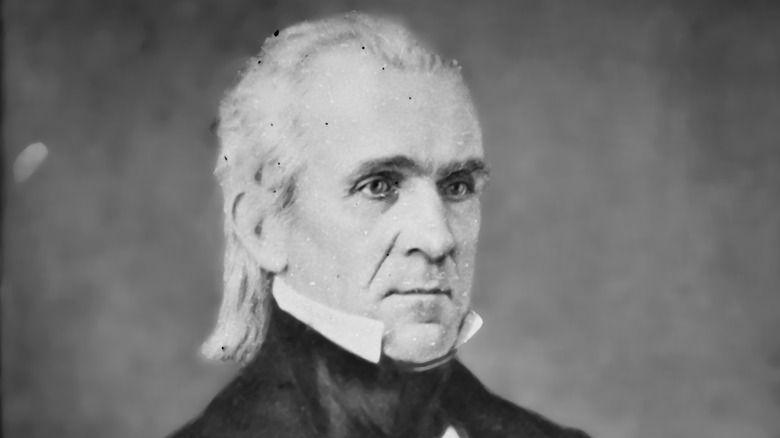

James K Polk

The territory of the United States first stretched from coast to coast under the presidency of James K Polk. The wars and treaties that won the Pacific for America represented the fulfillment of a campaign promise by Polk, promises that might have cost him the chance to become president in the first place.

With the crucial support of President Andrew Jackson, Polk entered the presidential race of 1844 with avowedly expansionist rhetoric. His national profile had been limited before then, a fact seized upon by the Whig opposition. But with Jackson behind him, Polk won the White House in 1845 and immediately pushed to bring Texas, California, and Oregon into the United States. According to the UVA Miller Center, he was the most successful president at implementing his stated agenda since George Washington, though he failed to anticipate the effects of expansion on enslavement and national unity.

Among Polk's promises was that he would only serve a single term, and he stuck to it. He left office on March 5, 1849, eager to be free of the responsibilities of president. But his health had collapsed over the four years he served. On June 15, just 102 days after his term ended, Polk died, possibly of complications from cholera he was exposed to while touring the South.

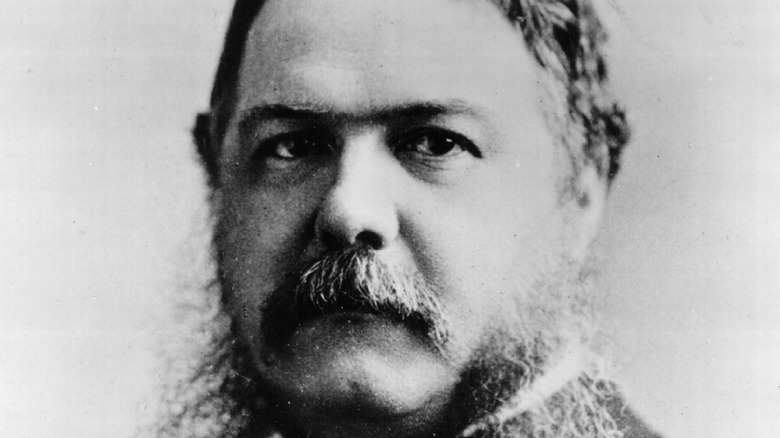

Chester A Arthur

Chester A. Arthur came into the presidency under inauspicious circumstances. He was a veteran of the New York political machine who resisted efforts to reform its system of patronage. While honest in his personal life and his own work, Arthur put Republican party loyalty over other virtues when staffing the New York Customs House.

Arthur's resistance to reform cost him his job in 1878, but party bosses got him on the 1880 Republican ticket as James Garfield's vice president. Garfield was a reform advocate, and Arthur initially opposed him from within the administration. But when Garfield was assassinated in 1881 by a man who wanted Arthur and his patronage system in office, the new president surprised everyone. He turned his back on the elements of the Republican party that had supported him and advocated the Pendleton Act, which created the Civil Service Commission and protected federal jobs from political retribution (per Britannica).

Unknown to the public, Arthur struggled with nephritis — then called Bright's disease — throughout his time in office (per the National Constitution Center). Mindful of his then-incurable condition, and having turned over a new leaf during his one term, he made only a token effort to win a second. Poor health frustrated his efforts to practice law in post-presidential life. Out of office on March 4, 1885, he died less than two years later, on November 18, 1886.

George Washington

Anyone known as the father of his country ought to have an impressive list of achievements to his name. George Washington's list includes his military service, first as a colonial soldier, then as a revolutionary general, and his efforts as a civic leader in his native Virginia. He presided over the creation of the U.S. Constitution, then served as the United States' first president. But among the most consequential actions Washington took in his lifetime was establishing the precedent of only serving two terms in the nation's highest office.

Washington had voluntarily surrendered power before, when he gave up his military commission at the end of the Revolutionary War. He had been a reluctant president who initially wanted to retire after a single term, but faced unanimous counsel against it. However, he held firm in 1796, delivering a famously cautionary farewell address to the nation and leaving office on March 4, 1797. Peaceful retirement was briefly threatened by tensions with France two years later; Washington was named commander of a provisional army in the event of war. But the situation was peaceably resolved.

At his home in Mount Vernon, Washington took up distillation and entertained a steady stream of visitors, though not always with enthusiasm. On December 12, 1799, he was caught in a snowstorm, took ill, and died two days later (per the UVA Miller Center). He'd had less than three years of the retirement he so often delayed for his country.

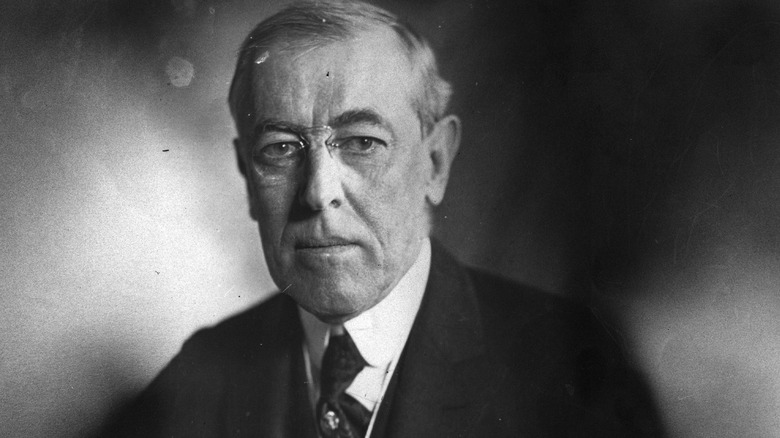

Woodrow Wilson

If Woodrow Wilson were to have had his way, March 4, 1921 would not have been the end of his presidency. By 1919, his domestic achievements included reformed finances, busted trusts, and a ban on child labor (alongside the less noble achievement of expanding segregation). Internationally, his leading of America into World War I clinched victory for the Allies, and he held up his proposed League of Nations as an ideal means of securing peace.

But Wilson's vision for the League didn't account for the animosity felt by the Allies towards Germany. Nor did he fully recognize the turn towards isolationism in America after the war. While campaigning — against his doctors' advice – to try and compel the Senate to ratify the League, Wilson suffered a massive stroke in September 1919. Left half-paralyzed, he was left dependent on his doctors and his wife, who relayed his uncompromising arguments for the League in an ultimately doomed effort at ratification.

Per the National Constitution Center, Wilson hoped that division within the Democratic party at the 1920 convention would get him nominated for a third term. When that gambit failed, he entertained visions of a return to power in 1924. But the party showed no enthusiasm for the prospect, and Wilson was in no condition to keep office. He became a virtual recluse in retirement, and he died on February 3, 1924, not quite three years after leaving office.

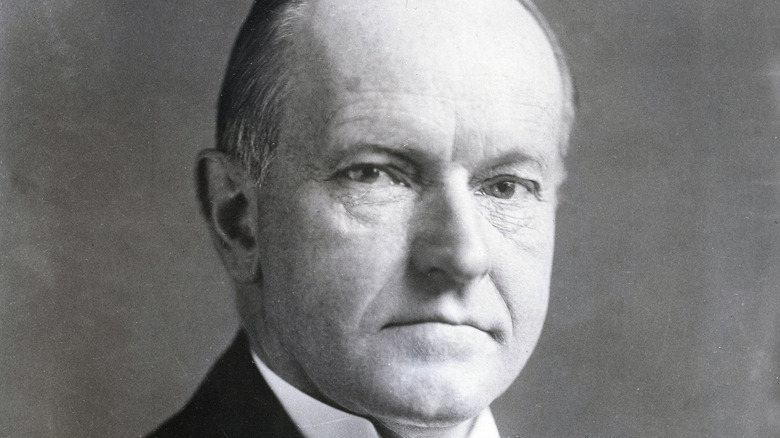

Calvin Coolidge

Presidential reputations evolve with time, and can sometimes depart greatly from what the president experienced while alive and in office. Calvin Coolidge, vice president in 1923, got the top job when Warren G. Harding died. Inheriting an office tarnished by Harding's scandals, Coolidge was widely beloved for his personal integrity, his dry wit, and his hands-off approach to government and economics.

But that laissez-faire attitude has seen his reputation slide over the years. Coolidge advanced no major policy initiatives, offered no sweeping visions for America's advancement, and his foreign policy was similarly unremarkable. And in the economic sphere, Coolidge's favored tax cuts and a detached approach to regulation were among the reasons for agricultural disasters and growing income inequality in the 1920s.

Coolidge lived to see his reputation begin turning. He turned down the chance for a third term in 1928, unwilling to break precedent and bereft at the loss of his son while in office. His time as president ended on March 4, 1929, and that same year, the Great Depression began. If Coolidge couldn't be held wholly responsible for the economic downturn, it did spark critical reevaluations of his presidency. As the crisis endured, he told a friend, "I feel I no longer fit in with these times" (via The White House). Coolidge died on January 5, 1933, just as the Roosevelt administration and its radically different vision of presidential authority was about to begin.

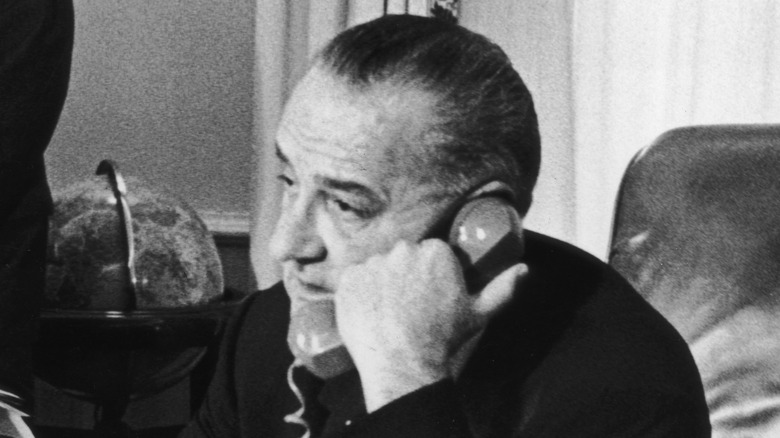

Lyndon B Johnson

No president has an unblemished record: There are policy failures, miscalculations, and moral compromises in every administration. But few presidential legacies have such dichotomous highs and lows as Lyndon B Johnson's. The Civil Rights Act and Great Society initiatives have improved the lives of millions of Americans since their passage. But the Vietnam War, which Johnson championed, is counted as a military disaster that shattered any hope Johnson may have had about running for another term in 1968.

Johnson's time as president ended on January 20, 1969. He returned to his native Texas tired and convinced by family history that he wasn't long for the world. Not that this convinced him to guard his health; he resumed smoking after a 15-year abstinence and only occasionally stuck to diets designed with his weak heart in mind. Johnson also alternated between buoyant activity and caustic bitterness over his perceived mistreatment by the American press. "[They] always accused me of things I didn't do," he once complained (via The Atlantic). "They never once found out about the things I did do."

Occasionally, Johnson would publicly volunteer political commentary, on his own legacy or the performance of President Richard Nixon. Within Democratic politics, his reputation and his enthusiasm for George McGovern's candidacy in 1972 was cool. In near-constant pain, he died on January 22, 1973, four years after leaving office and just before the Vietnam War came to an end.

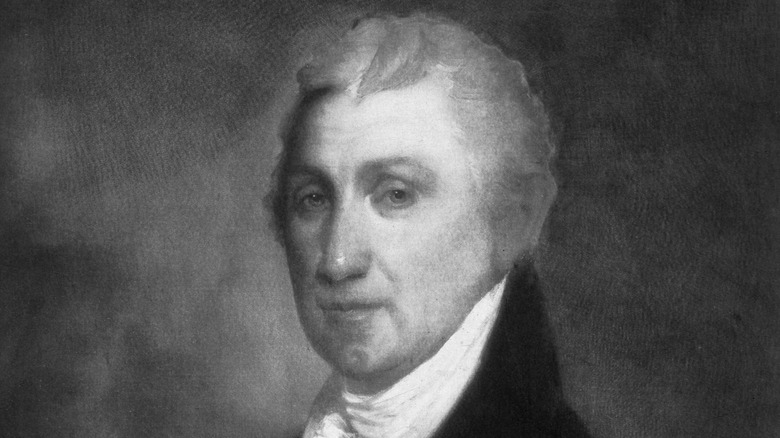

James Monroe

James Monroe was the last of the Founding Fathers to serve as president, and he dressed the part. Even as fashions changed in the mid-1800s, Monroe still went about in a tricorn hat and knee britches. His appearance, his long history of service to the nation, and his good reputation among his fellow founders made him a popular leader. His two terms in office have been described as the Era of Good Feeling.

That descriptor belies growing tensions within America during Monroe's presidency. Enslavement was an ongoing dilemma in his time: The Missouri Compromise headed off an immediate controversy about its expansion into new territories, but offered no long-term solutions. Monroe left a more lasting impression on foreign affairs with the Monroe Doctrine, stating U.S. opposition to any effort by European powers to recapture their former colonies in the Americas, or interfere in the New World's politics. Monroe initially considered a more narrow alliance with Britain against Spanish meddling in Latin America, but his secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, convinced him to go broader (per The White House).

In his many years of public service, Monroe was obliged to spend freely on limited salaries. And on retiring from office on March 4, 1825, he spent his last six years trying to settle his debts. His ties to the revolutionary generation were reinforced one more time when he died on July 4, 1831.

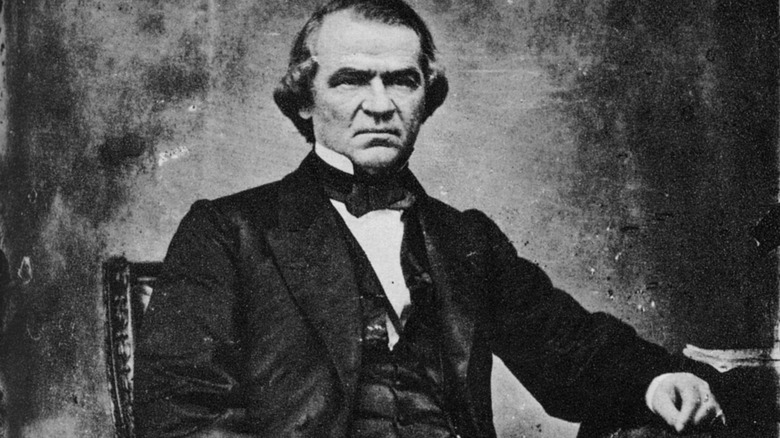

Andrew Johnson

Anyone succeeding Abraham Lincoln in the presidency would have a tall order measuring up, particularly in light of the circumstances that ended Lincoln's second term. But the wide consensus among contemporaries and historians has always been that Andrew Johnson was ill-suited to the task. Johnson was the only southern senator to stay loyal to the United States during the Civil War, and was chosen as Lincoln's vice president in 1864 to demonstrate a commitment to national unity. But as president, the southern, Democratic Johnson found himself at constant loggerheads with the Republican-led Congress, particularly on matters of reconstruction.

Johnson, a states' rights advocate, wanted broad amnesty for former Confederates and minimal interference from the federal government in southern state affairs. He was an open racist who opposed civil rights initiatives: The first 15 Congressional overrides of presidential vetoes were in response to his refusal to accept such legislation (per Politico). Members of Johnson's cabinet worked to limit his reach, and by the time he was impeached and narrowly acquitted for an alleged violation of the Tenure of Office Act, he was a lame duck.

Neither the Republicans nor the Democrats wanted Johnson in the election of 1868. He left the presidency in disgrace on March 4, 1869, but Johnson refused to retire from politics. Six years later, he felt he had achieved vindication when Tennessee returned him to the Senate. Only a few months into his term, however, Johnson suffered a stroke and died on July 31, 1875.

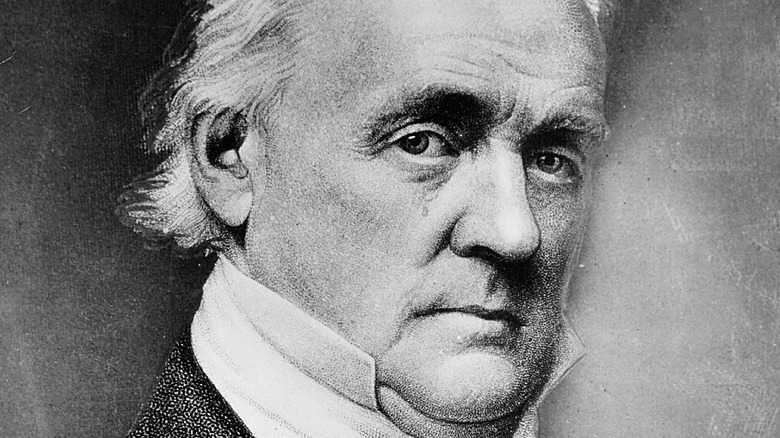

James Buchanan

When historians are asked to rank U.S. presidents, one name reliably appears at or near the bottom of the list. James Buchanan had ably served in Congress, in the cabinet, and as a minister abroad by the time he became the Democratic nominee for president in 1856. Years abroad left him without baggage in the increasingly bitter national debate over enslavement, but it also left him ill-prepared to deal with the issue when he was elected.

Buchanan wanted to diffuse the enslavement issue by letting the Supreme Court decide it through the Dred Scott decision, and staffing his administration with representatives of the North and South. The latter course appeased no one, and the court's ruling infuriated northern states. The Democrats split along territorial lines, the Republican party emerged as a powerful anti-enslavement force in Congress and the 1860 election, and Buchanan maintained that he had no authority to prevent moves by the South toward secession despite his personal opposition. Through his inaction and gridlock in Congress, the long-gestating Civil War began.

Leaving office on March 4, 1861, Buchanan maintained that he would be vindicated. He published a memoir in 1866 defending his legacy and pinning the blame for the war on Republicans, despite supporting the Union cause during the conflict (per the UVA Miller Center). He died seven years after his one term ended, on June 1, 1868.

Benjamin Harrison

William Henry Harrison has two distinctions in U.S. presidential history: the shortest-ever administration, and the only man to have a grandson follow him into the White House. Benjamin Harrison's relation to the war general served as a Republican riposte to Democratic attacks on Harrison's short stature (per The White House). A Senate record championing civil rights and war veterans got him his party's nomination in 1888, and backroom deals he was unaware of let him triumph in the electoral college, despite losing the popular vote.

As president, Harrison worked to expand America's international presence, invest in infrastructure, and made early efforts to challenge the power of business monopolies. But the nation's economy soured under his watch, and his tariff policy was controversial within his own party. In 1892, he lost to Grover Cleveland, the man he had defeated in the electoral vote four years earlier.

Harrison had eight years to enjoy life outside the White House. His wife having died during the 1892 campaign, he remarried to her niece. He practiced law in Indiana, delivered lectures, and briefly returned to public service in an arbitration dispute between Venezuela and Great Britain. He died on March 13, 1901.

Dwight D Eisenhower

If Dwight D Eisenhower had retreated from public life after World War II, he would have already been assured of a place in American, and indeed world history, for leading the Allied forces on D-Day. But he went on to assume command of NATO forces in 1951, and to win the presidency for the Republicans the following year. But from the White House, the former general looked at a hostile foreign climate and worked to cool the temperature.

Eisenhower increased spending on U.S. nuclear programs and issued veiled threats about nuclear attacks on hostile nations. He also authorized covert intelligence operations that sacrificed ethics in the name of containing communism (per the UVA Miller Center). But he also oversaw a peace settlement in the Korean War and worked to defuse tensions with the Soviet Union. Domestically, he continued many of the New Deal policies from previous Democratic administrations.

Eisenhower's two terms as president ended on January 20, 1961. Three days earlier, he gave his famous warning against the "military industrial complex" in a televised farewell address. He spent his retirement with his family on a farm near Gettysburg, with winters in California. He raised cattle, wrote two memoirs, and provided frequent counsel to his successors in the White House. Eisenhower died after a long period of ill health on March 28, 1969, eight years after the end of his presidency.

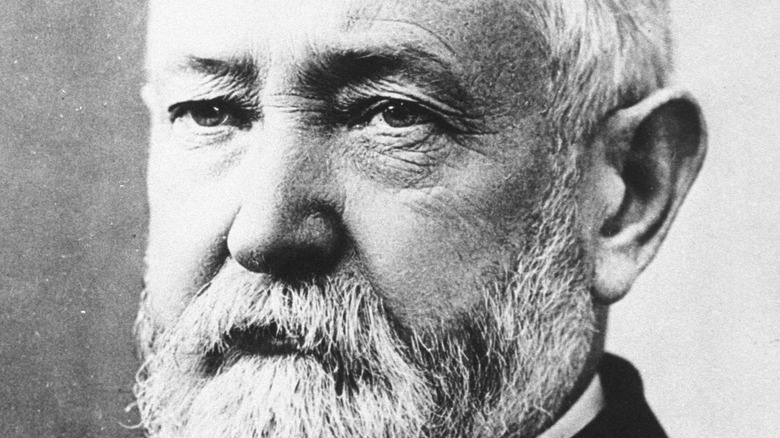

Andrew Jackson

In his time, Andrew Jackson was an oft-revered figure, seen as a war hero and a champion of the democratic system of government. In the 21st century, his support of enslavement, cruel policies towards Native Americans, and his personal hot temper have made him a much more contested figure. But his presidency could never be called inconsequential.

A rags to riches story (many of the riches coming from the work of his enslaved people, according to History), Jackson greatly expanded the powers of the presidency through his clashes with Congress and his firm control of the Democratic party. While fiercely opposed by Whig lawmakers, his immense popularity and advocacy for a democratized federal workforce turned the office into a bully pulpit for the national mood. And Jackson's influence extended well beyond his two terms. Two of his protégés, Martin Van Buren and James K Polk, followed him into the White House.

Jackson claimed to want a quiet retirement after he stepped down from the presidency in 1837, but he rarely stuck to that plan. He routinely threw advice Van Buren's way and, after his disciple's defeat in 1840, rallied opposition to the Whigs on the issue of expansion. His eight years out of office also saw him deluged with well-wishers and honors. Having defied death in war and illness many times during his life, he finally passed away on June 8, 1845.

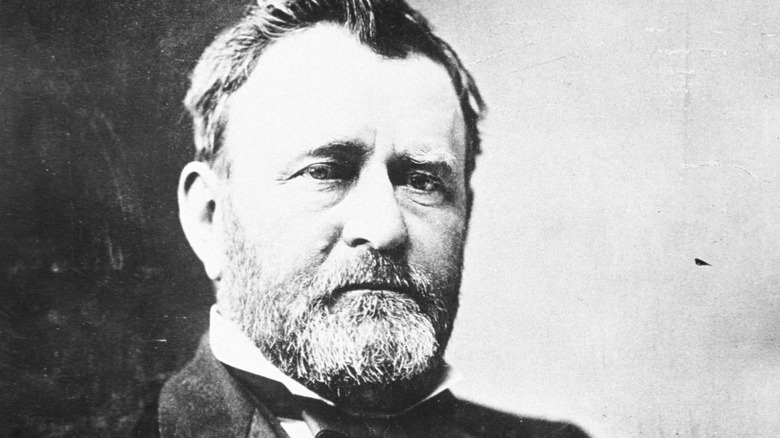

Ulysses S Grant

Assessments of Ulysses S. Grant and his presidency have run hot and cold over the decades. Concerted efforts by Southern historians painted an influential image of a drunken brute, who let corruption run rampant in his administration. That Grant, while personally honest, let shady characters into government out of naïveté is indisputable. Yet the Grant administration has seen its standing with historians rise considerably since a reexamination began in the 1990s.

Grant, who fought so fiercely to win the Civil War, was determined not to abandon newly freed Black Americans to Southern hostility. But he also wanted to mend the nation and expand the Republican party's appeal beyond the northern states. These earnest convictions were regularly at odds during his two terms, and without firm guidance from Congress, Grant struggled to find a path forward. Corruption at the state and federal level undermined confidence in government, and economic disasters hurt his administration. But he saw through the 15th Amendment and worked to turn the tide on Native American relations.

Grant left office in 1877, and indulged his love of travel with a two-year tour. He began writing his memoirs to leave his family some money, a task that gained urgency when he learned he had throat cancer. With help from Mark Twain (per the National Park Service), Grant secured a lucrative deal and completed his book days before his death on July 23, 1885. He had been out of office for a little over eight years.

Theodore Roosevelt

If you had to imagine a president destined for a long life out of office, they might well look like Theodore Roosevelt. Aged 43 in the first year of his presidency, he was the youngest president in American history yet. He survived an often sickly youth to become a vigorous outdoorsman, soldier, and campaigner. And his policies over his two terms dramatically expanded the power of the presidency, and the presence of America on the world stage.

At the end of his second term in 1909, Roosevelt seemed prepared to leave politics behind. But his chosen successor, William Howard Taft, proved too conservative for his mentor's liking. Roosevelt tried to take back control of the Republican party in 1912. Denied that, he created the Progressive party, popularly called the Bull Moose party after a personal assessment by Roosevelt of his vitality. He famously had a chance to demonstrate that vitality when he survived an assassination attempt and finished his 90-minute speech before going to the hospital.

Roosevelt remained a bitter political foe of Woodrow Wilson, who defeated him and Taft in 1912. Wilson's rebuffing of Roosevelt's championing the Allies in World War I, years before America at large was prepared to enter the war, did nothing to mend fences (per Britannica). Roosevelt's continued energy led Republicans to consider taking him back as a presidential nominee for the 1920 election, but Roosevelt died on January 6, 1919, just shy of a decade since leaving the White House.