The First Black Female Lawyer In America Was Born In The 1800s

Over 150 years ago, Charlotte E. Ray became the very first Black woman to graduate law school and be admitted to the bar in any state in the United States. Unfortunately, due to racist segregation and gendered prejudices, Ray's legal practice didn't last long. But in her footsteps would follow other Black women like Jane Bolin and Barbara Jordan, who were able to have the legal careers that they wanted.

But Ray wasn't the only Black woman in the 19th century trying to become a lawyer. There were other Black women even in the same law school as her that were kept from graduating even though they entered the law school in the same year. But because of Ray's family influence, as her father was a famous abolitionist, Ray was afforded many more opportunities earlier on than other Black women were at the time.

This is often the case with people who are able to achieve success. There wasn't necessarily anything in Ray that made her the only Black woman most capable of becoming a lawyer. There were thousands of Black women at the time that could've become outstanding members of the legal community. But because Ray's family was able to afford an education for her while she was growing up and was able to secure her graduation from law school, Ray found herself in a much more privileged position than most. This is the story of the first Black woman lawyer in America.

Charlotte Ray's early life

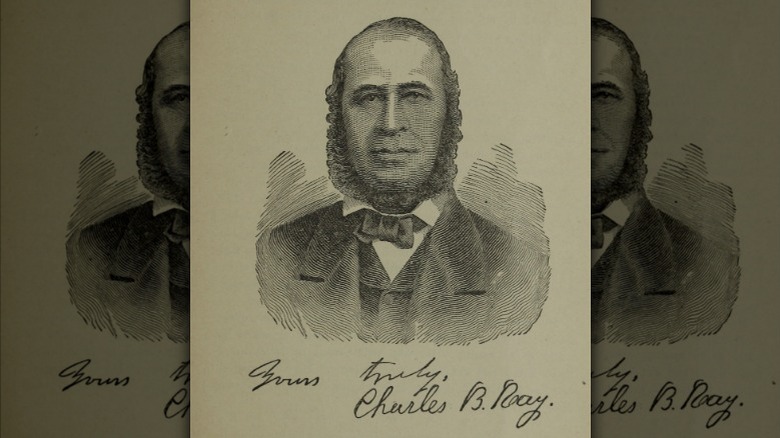

Born in New York City, New York on January 13, 1850, Charlotte E. Ray was the seventh child of Charlotte Augusta Burroughs Ray and Reverend Charles Bennett Ray. Growing up, young Charlotte E. Ray was introduced to concepts like abolition and justice early on because of her father's work as an editor at the abolitionist newspaper, The Colored American, in addition to his work as a member of the Underground Railroad. The year Charlotte E. Ray was born, Rev. Charles Ray was even a speaker at the 1850 Cazenovia Convention, the largest meeting of enslaved people who were fugitives against the proposed Fugitive Slave Act.

After her family moved to Washington, D.C., Charlotte E. Ray was enrolled into the Institution for the Education of Colored Youth, later renamed the Miner Normal School, which was one of the few places in the country that allowed Black girls to enroll. "Women in American History" writes that after Charlotte E. Ray graduated in 1869, she was hired as a teacher by the Preparatory and Normal Department of Howard University.

Charlotte E. Ray also wasn't the only one in her family to go into teaching. In "Women: The American History of an Idea," Lillian Faderman writes that both Charlotte E. Ray's sisters, Henriette Cordelia Ray and Florence Ray, became elementary school teachers. However, Henriette Cordelia Ray would later leave teaching to devote herself to writing poetry.

Teaching at Howard University

At Howard University, Charlotte E. Ray taught at the Normal and Preparatory Department, the University's prep school. Her classes were focused largely on training other students, the majority of whom were other women, on how to be a teacher or preparing them for more advanced studies. However, the position offered no potential advancement for Ray's own career. Seeking something more engaging, Ray applied to Howard University's School of Law in 1869.

There are various stories surrounding Ray's admission into Howard University's School of Law, but the most common account involves her using her initials to dispel any initial thoughts about her gender. According to The Green Bag, Ray applied for admission under the name C.E. Ray and "there was some commotion when it was discovered that one of the applicants was a woman." Ray also continued to teach at the Normal and Preparatory Department while she attended the law school in the evenings from 1869 to 1872.

According to "Sisters in Law" by Virginia G. Drachman, Ray wasn't the first Black woman to enroll at Howard Law School. Anti-slavery activist and writer Mary Ann Shadd Cary also enrolled in 1869.

Howard's School of Law

Although Black women were able to attend Howard University's School of Law, they still experienced a great deal of misogyny and misogynoir from the men around them. According to "Black Women in America," when Charlotte E. Ray presented a paper on corporations in 1870, a trustee who was visiting was reportedly shocked that a Black woman "read us a thesis on corporations, not copied from books but from her brain, a clear incisive analysis of one of the most delicate legal questions."

But despite the backhanded compliments, there were those who recognized Ray's aptitude for the law. Lawyer and politician James Carroll Napier, who was later part of President WIlliam Howard Taft's Black Cabinet, was a classmate and friend of Ray's during her time at Howard's School of Law and described her as "an apt scholar," according to "Democracy, Race, and Justice" by Sadie T. M. Alexander.

During her law school studies, Ray focused on studying corporate law. When she graduated in February 1872, she became the first woman in the United States to graduate from a university-affiliated law school. Although Howard Law School required three years to graduate, Cary wouldn't graduate until 1883. Virginia G. Drachman writes in "Sisters in Law" that Cary wasn't allowed because of her gender, but it's peculiar that Ray was allowed to graduate after three years while Cary was not. By the end of the 19th century, only seven other women had graduated from Howard University's School of Law.

The first Black woman attorney

After Charlotte E. Ray graduated from Howard University's School of Law, she was admitted to the Bar of the District of Columbia shortly afterwards. This made Ray the third woman in the United States ever to graduate from law school, the first Black woman attorney and the very first woman to be a lawyer in the District of Columbia. The first woman in the United States that was ever admitted to a state bar was Arabella Mansfield in Iowa in 1869. And according to "Notable American Women, 1607-1950," because the D.C. legal code had taken the word "male" out in regards to bar admission, Ray didn't face any issues with the D.C. Bar.

In May 1872, the Women's Journal wrote about Ray's admission to the D.C. Bar, underlining how just 10 years early, enslavement was legal and still commonly practiced in the nation's capital; "In the city of Washington, where a few years ago colored women were bought and sold under sanction of law, a woman of African descent has been admitted to practice at the Bar of the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia," per "Democracy, Race, and Justice" by Sadie T.M. Alexander.

Opening her own practice

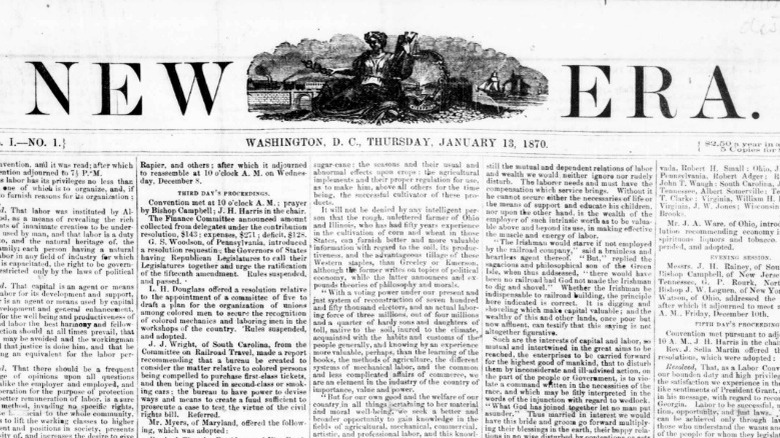

After graduating and being admitted into the D.C. Bar, Charlotte E. Ray opened her own practice with a focus in corporate and commercial law, additionally making her the first woman lawyer to specialize in corporate and commercial law. Ray advertised her legal practice in Frederick Douglass' weekly newspaper, the New National Era and Citizen and, according to "Emancipation" by J. Clay Smith Jr., her legal skills didn't go unnoticed. Although she only actively practiced law for a few years, she soon became known as "one of the best lawyers on corporations in the country." "Women in American History" writes that Douglass would even write about Ray's legal achievements in articles.

Throughout her legal career, Ray had also maintained the activism instilled into her by her father, and she participated in the National Woman's Suffrage Association in 1876.

But even then, misogyny persisted and no matter her achievements, the qualifier "for her sex" was often added to any acknowledgement of her legal skills. Ultimately, Ray would continue actively practicing law for just a few more years until "on account of prejudice [she] was not able to obtain sufficient legal business," Chicago Legal News reports (via Stanford University).

Arguing in the D.C. Supreme Court

Although Charlotte E. Ray reportedly focused her legal practice on corporate and commercial law, in 1875 Ray argued a case in the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia regarding a domestic violence situation. In Gadley v. Gadley, a Black woman named Martha Gadley had filed for divorce against her abusive husband, but the petition for divorce had been dismissed by the lower courts, according to "Women In American History."

Arguing on behalf of Martha Gadley, Ray asserted that she was entitled to a divorce because her husband's abuse was threatening her life. In pleading the case, The Philadelphia Sunday reports that Ray argued that the husband's alcoholism and abusive treatment that "endanger[ed] the life or health of the party complaining" were justifiable grounds for divorce. According to the Howard Law Journal (via the League of Women Voters of Indiana), Charlotte's petition describes some of the abuse suffered by Martha Gadley, including being locked out of her own house and having her clothes thrown outside. And in a decidedly rare ruling, the Supreme Court of the District of Columbia ruled in favor of granting Martha Gadley a divorce.

When lawyer and author J. Clay Smith later discovered the pleading written by Ray, he remarked on her "technical knowledge and skills to plead and to practice before the courts of the District of Columbia," according to "Charlotte E. Ray Pleads Before Court" (via Stanford University).

Charlotte Ray's final years

In 1879, Charlotte E. Ray moved back to New York City, New York. After seven years of keeping a legal practice, both racist and gendered discrimination kept her from maintaining a successful practice, according to "Women in American History." Upon moving back to New York City, Ray resumed her teaching career in the Brooklyn public school system where her sister Florence Ray reportedly worked as well. After moving back to New York City, she continued to participate in activism by joining the National Association of Colored Women in 1895.

Other than her teaching career and membership in the National Association of Colored Women, there is practically no information regarding Ray's life in New York City. She reportedly married in 1886, but there are no other records of her until her death in Woodside, New York on January 4, 1911. However, this could be due to misspelled records, as her cemetery records write her married name as Fraim while newspapers reported it to be Traim, so even her correct married name remains a mystery.

While it's likely that she continued in her activist work, there are no records of Charlotte E. Ray ever reapplies to the New York Bar and it appears as though her legal career, with all its achievements, was unfortunately very short-lived.

Charlotte Ray's legacy

In the 21st century, Charlotte E. Ray's legacy continues to be celebrated and remembered. The non-profit Minority Corporate Counsel Association awards the Charlotte E. Ray Award to a woman lawyer every year "for her exceptional achievements in the legal profession and extraordinary contribution to the advancement of women in the profession." During Black History Month, many law firms will also shine a spotlight on Ray.

Unfortunately, celebrating Ray's life and career does little to materially affect the discrimination and prejudice that Black women attorneys continue to face today. According to the Report on Diversity in U.S. Law Firms 2022, in 2022, only 10.15% of all lawyers were women of color and only 2.12% were Black women.

Harvard Business Review also reports that non-white people, especially Black women, often hear criticism like "You don't look like a lawyer" as the idea of being a lawyer is associated with the idea of being a cisgender white man. Additionally, non-white attorneys, including Black women, are frequently forced to put in significantly more uncompensated labor than their white colleagues, something that author Tsedale M. Melaku refers to as the "invisible labor clause."