The Real Frank Serpico: The NYPD Whistleblower Who Exposed Police Corruption

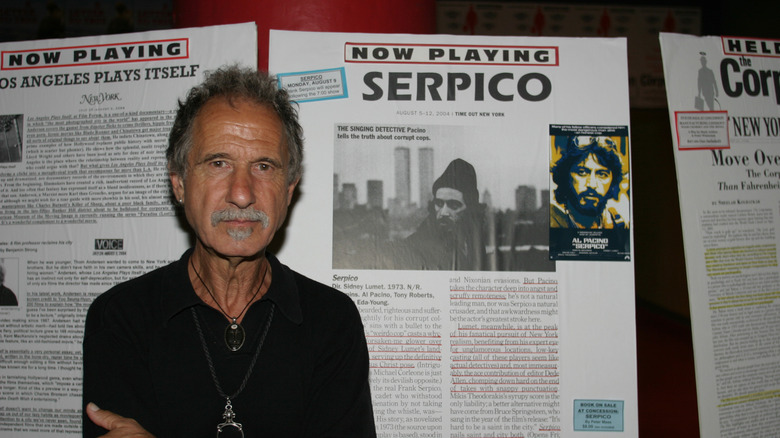

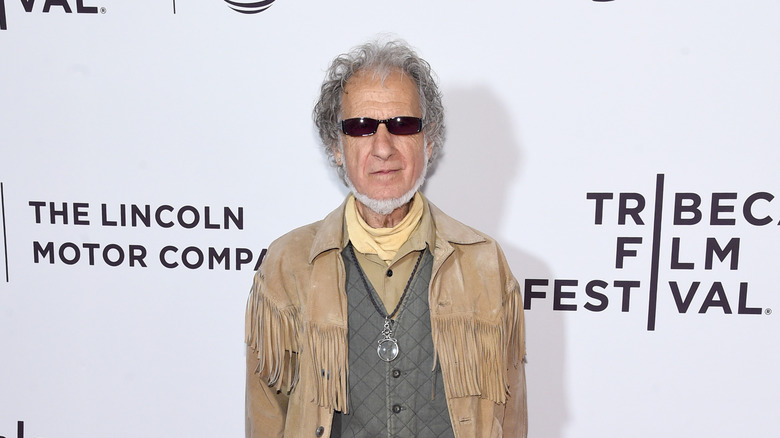

Frank Serpico was an NYPD cop who shot to fame for exposing widespread corruption and cop-on-cop crime within the police force in the early 1970s. Made legendary by "Serpico," the movie version of his life starring Al Pacino, the real-life Serpico was just as cool as Hollywood's imitation — a hippy bohemian who loved to bust bad guys.

The idealistic young cop joined the force with a real passion to do good, however, he quickly discovered that his colleagues broke the law with impunity, enriching themselves with bribes whenever they could. An inspiration to good cops everywhere — and a rat to bad ones — Serpico willingly took his story public after a long battle to hold his fellow officers accountable. Now known as one of history's great whistleblowers, Serpico faced considerable opposition and even risked his own personal safety to seek justice.

The Knapp Commission that resulted from his whistleblowing led to a rare attempt to clean up the force and do away with systemic corruption. But while Serpico did a lot of good, he would pay dearly for his crusade. Not long after his story went public, he was abandoned in a moment of crisis — a bullet lodged in his head.

Serpico's early life and character

Frank Serpico knew from a young age that he wanted to be a police officer. Born to Italian immigrant parents, Serpico grew up in New York but spent several years in the army in South Korea. The Whistleblower Network recounts that he had a tough character and his father imbued him with a strong moral compass growing up, telling him to "Never run when you are right." Serpico took this advice to heart.

Despite his long-held dreams of being an officer, Serpico was no stereotypical macho cop. As a young man, he lived in the counter-culture capital of New York, Greenwich Village. He loved opera and jazz and taught himself Spanish. A real child of the '60s, when he started working for the police, he wore sandals and kept his hair long. Women loved him, but to the police, he was a bit of a weirdo.

Joining the force in 1959, it looked as though he had a promising future ahead of him. He proved to be a crack shot at the academy and he garnered great respect among his peers for booking two armed robbers as a fledgling recruit. His instructors believed he would get a medal for the heroic arrests, but he was later passed over in favor of an inspector's son. It was an early taste of the widespread corruption he would experience throughout his career.

Serpico experiences his first bribe

Whatever romantic illusions Frank Serpico may have had about the heroic nature of the police force, they were soon destroyed. As a young officer, he found that the day-to-day taking of bribes had become a fact of life in the NYPD, and he was disgusted to learn that innocent people were sometimes punished due to widespread corruption. The police took money from all kinds of criminals, acting as much like the mafia as the mafia itself. Many cops saw the taking of bribes as an easy source of extra money that was too good to pass up. Serpico told The New York Times that one officer told him, "I don't care what they offer me — a thousand, a hundred, $2, I'll take it."

According to the account given by Peter Maas' in his biography "Serpico," Serpico first encountered this sort of bribery while working with another cop at the scene of a traffic violation. The man Serpico and his partner stopped had run a red light and when they pulled him over, they discovered he had several other traffic offenses to his name. The man offered Serpico a $35 bribe to look the other way. When Serpico went to tell his partner, the other officer simply took the money, nonchalantly offering to split it with Serpico 50-50. It proved to be just the first of many troubling encounters.

He butt heads with other officers

One of the most striking things about Frank Serpico's account of his time on the force is just how hard it was for him to not get sucked into the world of dirty policing. Serpico often gave away his share of any police bribes. But for a long time, that was all he did ... ignore it.

According to Peter Maas' "Serpico," Serpico's willingness to forego his slice of the cash actually made him the ideal partner for officers looking to enrich themselves. However, his ironclad integrity also got on peoples' nerves. For example, on one occasion, a fellow officer tried to give Serpico $100 given to him by a perp. When Serpico refused, he was given a lecture. While they were sitting in the police car, the officer explained to him that he was missing out on hundreds of extra dollars a month. He followed up his speech by warning Serpico that his refusal to join in on the police racket was not a popular decision. He revealed that someone had phoned his coworkers to warn them that he was untrustworthy and didn't play ball.

Serpico had started to stand out as an oddity and it did not help that he already did not fit into the extremely macho police environment. He bemused other officers with his hippy-like appearance and behavior, and his disinterest in sports. Refusing to spend much time socializing with other cops, he quickly became the subject of suspicion.

Serpico experienced serious opposition when he tried to report corruption

One day, a fellow plainclothes officer handed Frank Serpico $300 in an envelope from somebody called "Jewish Max." The sizable wad proved to be the final straw. Serpico decided he had to report the corruption to somebody.

But reporting the bribe proved to be more difficult than expected. Serpico went to fellow officer David Durk — now also legendary for his whistleblowing — and Durk advised Serpico to take his story to Captain Philip Foran. Although Durk was an honest cop, it turned out that he had misjudged Foran, who was not. According to Peter Maas' "Serpico," Foran warned Serpico that if he pressed the matter any further "they'll find you face down in the East River." Years later, when the corruption case went public, Foran's name got dragged through the mud for trying to stop Serpico's investigation, although he denied he did any such thing.

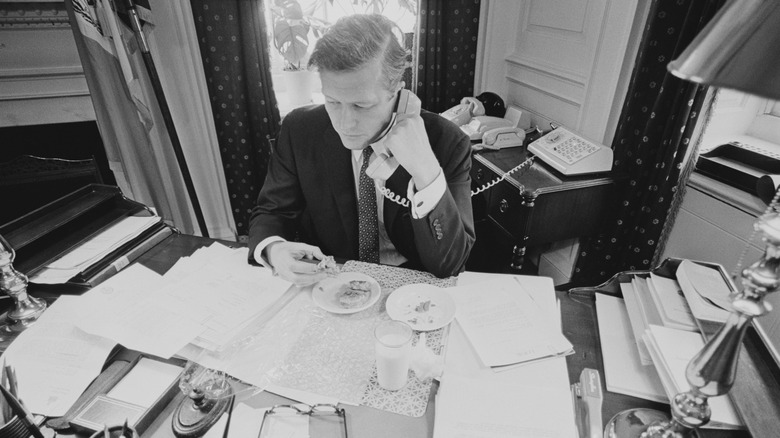

Looking for other avenues, Serpico continued to press the matter, but it did little good. At one point he even gave his information to Durk's contact at the Mayor's office. In short order, word got back to Serpico that Mayor John Lindsay did not want to meet to discuss the matter because he did not want to upset the police. Running out of options, things got increasingly dangerous for Serpico as word spread that he was a troublemaker. At one point, an officer even threatened Serpico's life, pushing a gun against his stomach.

Serpico gets transferred

Late in his career, Frank Serpico was transferred out of his police department to begin working for the NYPD's narcotics division. It would be one of the last jobs he ever did, and the story about police corruption would break while he was working at the department.

Working the drug beat turned out to be no better than the other jobs Serpico had been put on. He found that police filled their arrest quotas by going after people on possession charges and small-time dealers, doing little to tackle the roots of the heroin problem in New York. Like other departments, they were up to their neck in bribes.

Per, Peter Maas' "Serpico," the narcotics cops also considered Serpico a cause for concern. Shortly after joining the team, he was asked to go in on the drugs racket with his fellow police officers. After asking him if he was wearing a wire, one of the other cops told Serpico just how much money he could make off of drug deals. Turns out, it was an eyewatering amount compared to bribe-takers in other departments. The officer finished his speech by telling Serpico to get on board, "wise up," and save his reputation.

Going to the press

After failing to solve the problem internally, Frank Serpico and his friend Officer David Durk decided they had to go to the press. This time, their plan worked. According to Peter Maas' account in "Serpico," Durk had contact with The New York Times reporter David Burnham, who agreed to interview Durk, Serpico, and two other officers. Burnham subsequently ran a series of explosive articles on police corruption using the information they gave him.

Those involved in covering up the corruption scrambled to control the damage. The mayor's office was given word about the news stories in advance and immediately announced a plan to create a special investigative panel to look into the matter. Captain Philip Foran, on the other hand, who had also blocked Serpico's attempts to report the bribery, took a different tact. Foran responded to the accusations by calling Serpico both a psycho and a possible homosexual.

The first article The New York Times printed on the bribery scandal ran on April 25, 1970. The dramatic headline read "Graft Paid to Police Here Said to Run Into Millions." Pulling no punches, Burnham called out both the mayor and senior police officers for their failure to do anything about corruption.

The Knapp Commission

Mayor John Lindsay's planned committee to investigate corruption in the police was quickly shot down by critics. The Police Commissioner was among the men who had been appointed to Lindsay's investigative panel and unsurprisingly there was a strong call for a more independent inquiry into the matter. Instead, the Knapp Commission was created, headed by Lawyer Whitman Knapp. The Knapp Report which the committee produced, divided corrupt police into grass-eaters — officers who went along with the corruption — and meat-eaters — police who made a serious effort to push for bribes. It was felt that among them, the grass-eaters may be reformable.

Frank Serpico was among those who gave testimony at a public hearing for the Knapp Commission and following his questioning, he read out a powerful statement, later reprinted in The New York Times. "We must create an atmosphere in which the dishonest officer fears the honest one and not the other way around," he said. "Police corruption cannot exist unless it is at least tolerated at higher levels in the department."

The Knapp Report ultimately concluded that the police were involved in corruption at all levels in the NYPD. Shockingly, it also revealed that the police were heavily involved in the city's illegal drug trade. The New York Times reported that at least 40 policemen were indicted shortly after the Knapp Commission presented its findings.

Serpico gets shot

The animosity between Frank Serpico and his fellow police officers finally came to a head on February 3, 1971, when Serpico was on duty doing a drug bust. During a dramatic confrontation with a drug dealer, Serpico was shot in the face and left to die.

That day, Serpico and two other officers had gone up to a drug dealer's apartment, and Serpico had asked the dealer for drugs. When the door opened slightly, Serpico used his shoulder to break in, charging against it and snapping the chain lock. However, before he could get into the room, the door was hastily shut on him again, trapping him against the doorframe. While he was stuck in the doorway, the dealer stuck a gun in Serpico's face and fired. The other officers did not stick around to find out what happened next, and Serpico was only saved thanks to an old man in the building, who called the police on Serpico's behalf. Despite their inaction, the two other officers received medals for their work.

Thankfully, the bullet had missed Serpico's brain by a hair, hitting him in the back of the jaw instead. Although he would ultimately pull through, not everyone was happy about his recovery. While he lay in the hospital, a get-well card arrived for him. It had been edited to read "die quickly, scumbag."

Serpico received the NYPD Medal of Honor ... twice

Frank Serpico did not receive any awards for whistleblowing, but after taking a bullet to the face, the NYPD finally gave him the Medal of Honor in 1971. According to Politico, Serpico later put this down to the actions of one unusually noble Police Chief Sid Cooper. However, Cooper's desire to reward Serpico was clearly not shared by the many other officers.

The medal was given to Serpico with no ceremony and no paperwork. "[T]hey handed the medal to me like an afterthought, like tossing me a pack of cigarettes," he later recalled. Dislike of Serpico ran deep in the NYPD. Later in life, Serpico would find hate-filled messages about himself on an NYPD forum, and in an interview conducted in 2017, he revealed he was still getting police hate mail decades later.

Over 50 years after the Knapp scandal occurred, in 2022, Serpico received a second inscribed medal of honor in the mail, this time with his certificate included. AP News recounts that Serpico tweeted a picture of the certificate, which read, "in recognition of an individual act of extraordinary bravery performed in the line of duty."

Leaving the force

After Frank Serpico's brush with death, he decided to leave the force in 1972. Although Serpico had survived being shot in the face, he was left with serious PTSD, and fragments of the bullet still lodged in his head. Speaking to The New York Times in 2010, he lamented "I still have nightmares ... I open a door a little bit and it just explodes in my face."

Turning in his badge after receiving his medal of honor, Serpico went on to become more and more the hippy he had always been heart. His brush with death had resulted in an out-of-body experience, which would inevitably push him to spend a great deal of time thinking about spirituality.

He spent the next 25 years traveling around Europe and North America, and although the Knapp Commission and "Serpico" (the hit film about his life starring Al Pacino) would make him famous, he eventually settled down to a simple life, retreating into solitude. As an older man, he embraced meditation, living a peaceful existence out in the woods with no TV or internet connection. Despite a life dedicated to healing, he would remain deeply regretful that he had to give up on his dream career.

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.

Serpico speaks out on justice and corruption

Later in his life, Frank Serpico continued to speak out on matters of justice, giving interviews in newspapers and magazines on a huge range of policing issues from police brutality to the militarization of the police. He has remained adamant that the Knapp Commission did not end the systematic corruption that plagues policing.

Following the murder of George Floyd, Serpico reemerged in the public eye to speak about police racism. Talking to Foreign Policy Magazine, he stressed that police corruption has not gone away and that he remembers the racism well. He stated, "There is something in the culture that is unmistakably racist. ... A lot of people of color have PTSD over this, whether white people, especially cops, understand that or not."

Today, Serpico's status as one of America's most well-known whistleblowers has made him a hero to many, especially his fellow police officers. Speaking to The New York Times, a long-retired Serpico mentioned that concerned officers often vent to him about the corruption they are still dealing with today, saying, "An honest cop still can't find a place to go and complain without fear of recrimination."

If you or someone you know needs help with mental health, please contact the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, call the National Alliance on Mental Illness helpline at 1-800-950-NAMI (6264), or visit the National Institute of Mental Health website.