Life-Changing Innovations Of The 1940s: From Penicillin To The Jet Engine

Every decade has its fair share of innovations, but the 1940s really set the stage for a whole new world. Ranging from life-saving medicine to life-ending weapons, few can argue that people's lives weren't impacted by the advances of the 1940s.

Some of the inventions came as a direct result of the Second World War, which pushed countries all around the world to innovate in order to gain an upper hand. Other inventions came out of an indirect result of the Second World War, with someone being inspired in an instant or making do with what was available. And some just came out of dedicated and focused work that may not have had an end in sight. But through it all, new ideas came and flourished.

But no matter how these innovations came about, they changed the lives of millions of people all over the world. Air travel as we know it came into being in the 1940s, as did our ability to take care of our pet's waste. Nobody knows where the next innovation will come from, but it could just be the one that changes the world. These are some life-changing innovations of the 1940s: from penicillin to the jet engine.

Penicillin

Before the invention of penicillin, there was no reliable cure for bacterial infections like pneumonia, meningitis, and syphilis. Infections were treated with bloodletting, compounds like mercury, or herbal remedies instead, according to The Conversation. In the case of diseases like syphilis, people ended up with ulcers and sores all over their body and face and often ended up losing parts of their nose and lips as a result.

After the penicillin mold was discovered in 1928, researchers didn't produce pure penicillin until 1940. But by 1943, the United States started producing penicillin for soldiers in World War II. The mortality rate from untreated infections during wars was staggeringly high and the distribution of penicillin to soldiers was a game-changer. According to The Washington Post, by 1944 roughly 100 billion units of penicillin was being produced per month, "enough to treat every Allied casualty." The University of Oxford writes that by March 1945, penicillin was made available to the public in the United States. In the United Kingdom, it would become available to the public by the following year. It's impossible to say exactly how many millions of lives have been saved through the invention of penicillin.

Unfortunately, just because penicillin was invented didn't mean that everyone got immediate relief from medical ailments. In fact, the United States Public Health Service purposefully infected people in Guatemala with syphilis from 1947 to 1948 in an attempt to create a prophylactic despite having already discovered penicillin as a cure.

Kidney dialysis machine

The kidneys are an essential organ for filtering blood and producing urine. And different treatments for kidney failure have been recorded as far back as ancient Rome. These treatments often involved bloodletting and sweat therapy, but kidney failure was typically irreversible.

Although there were dialysis treatments pioneered by the end of the 19th century, the first successful kidney dialysis machine was invented by Dutch physician Willem Kolff. And according to "Doctors and Discoveries" by John Simmons, the first person that Kolff saved with the kidney dialysis machine was Sophia Schafstadt, a 67-year-old woman who was a known Nazi collaborator. Although Kolff was reportedly encouraged to let her die, he used his newly created kidney dialysis machine to bring her out of a uremic coma in September 1945.

According to the University of Washington Magazine, kidney dialysis continued to be considered experimental until the 1960s and was only used on a temporary basis, relying on people's kidneys to recover themselves. But in 1960, Belding Scribner thought of creating a shunt to keep blood flow high in the kidneys in-between dialysis treatments, which "took something that was 100 percent fatal and overnight turned it into 90 percent survival." Since then, people have been able to extend their lives by spending years on kidney dialysis machines. According to CNBC, roughly 100,000 new people in the United States are put on kidney dialysis machines every year.

AK-47

While some life-changing innovations gave the ability to save numerous lives, some life-changing innovations involved the ability to take countless lives away. With the invention of the Avtomat Kalashnikova, also known as the AK-47, it became easier for one person to kill numerous others at once, since it has the ability to fire 600 rounds in a single minute. The assault rifle was also revolutionary because it was inexpensive, lightweight, and reliable in different climates.

In 1947, Russian general Mikhail Kalashnikov invented the AK-47 assault rifle after seeing German firearms during World War II. Named after him, the AK-47 soon became the official assault rifle of the Soviet Army, writes The Conversation. Other countries in the Warsaw Pact also started using it as well. CBS News reports that Kalashnikov himself even once claimed that "American soldiers would throw away their M-16s to grab AK-47s and bullets for it from dead Vietnamese soldiers." The AK-47 has become such a popular firearm that it's estimated that one out of every five firearms worldwide is a variation of the Kalashnikova, per NPR, and it's known as the "most abundant weapon on earth."

In response to the Soviet AK-47, the United States Army invented the AR-15. And according to The New York Times, the majority of mass shootings in the United States are committed with variations of either AK-47s or AR-15s.

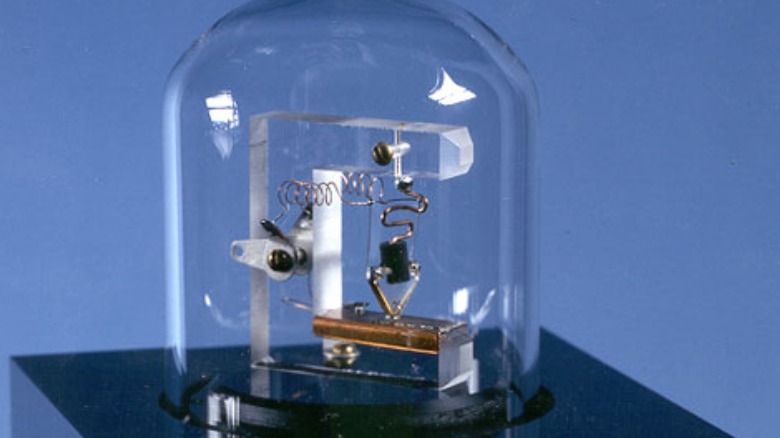

The first transistors

The point-contact transistor has been described as "the most important invention of the 20th century," according to WIRED Magazine. It set the stage for creating integrated circuits, or computer chips, that power modern computers. Before the 1940s, early computers used vacuum tubes to switch or amplify the flow of electrons. And while these vacuum tubes were more efficient than the previously used mechanical relays, they were still large, fragile, and expensive.

In 1947, American physicists John Bardeen and Walter Brattain were working at AT&T's Bell Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey when they created the first transistor using gold foil, a plastic triangle, and a germanium crystal, writes PBS. By using gold foil instead of wires, they were able to create metal contacts within 0.002 inches apart from one another. Meanwhile, the germanium worked as a semiconductor and allowed for the amplification of the input signal.

The first transistor was demonstrated just before Christmas Eve 1947 and was publicly announced about six months later on June 30, 1948. But by this point, the innovations were just getting started. Physicist William Shockley, who'd organized Bardeen and Brattain to research replacements for vacuum tubes, invented the bipolar junction transistor in early 1948, which continues to be used to this day. Shockley's invention of the bipolar junction transistor was largely done out of spite, due to the fact that Shockley wasn't included in the reveal of the point-contact transistor despite having instigated the research.

Microwave oven

Sometimes, ingenious innovations are found entirely by accident. Even when Dr. Alexander Fleming first discovered penicillin in 1928, it was only because of accidental mold contamination. And turns out that the microwave oven has a similar history of infusing an unrelated experiment with an accidental discovery.

In 1946, American physicist Percy Spencer was working as an engineer at Raytheon, a defense contractor, and was researching radar magnetrons, reports Popular Science. And it was during an experiment with the magnetron tubes that Spencer discovered the candy bar inside his pocket had completely melted. After a few more experiments, Spencer realized that he was not only creating microwave energy but that it could even cook food. Spectrum Magazine writes that Spencer promptly filed a patent for microwave cooking, but it would take some time before microwaves caught on with the public.

The very first commercial microwave was released by Raytheon in 1947 and was called the Radarange. However, it cost almost $2,000 at the time, was the size of a refrigerator, and weighed 750 pounds. It wouldn't be until 1967, when a compact version of the Radarange was released by Amana, that microwave ovens started to make their way into American homes. By the 21st century, microwaves are used as often as 1,000 times per year by households in the United States, according to "Surveys of Microwave Ovens in U.S. Homes."

Synthetic cortisone

Black American chemist Dr. Percy Lavon Julian's work in synthesizing medical compounds from plants and beans in the United States is some of the most significant medical work of the 20th century. His innovations include synthesizing physostigmine from the Calabar bean as well as progesterone and testosterone from soybean oil. Additionally, Julian is also known for synthesizing cortisone from soybeans in the 1940s, and with his innovations, hormones were able to be produced on a massive scale.

Cortisone is an adrenocortical hormone, also known as a steroid hormone, that is naturally produced by the adrenal gland in the brain. After cortisone was isolated by the Mayo Clinic in 1948, it took Julian just one year to synthesize both cortisone and hydrocortisone. According to the "Magic Bean" by Matthew David Roth, cortisone was initially able to be derived from ox bile. But it would take 14,600 oxen to treat one person with arthritis for just a single year. But Julian figured out how to synthesize cortisone from soybeans, dropping the cost of production down to pennies.

The invention of synthetic cortisone and hydrocortisone was a game changer in medical treatment. The treatment of adrenocortical deficiencies became possible, as did conditions like psoriasis, eczema, and asthma. Neuroimaging Pharmacopoeia also notes that synthetic corticosteroids are essential in treating autoimmune conditions like lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and multiple sclerosis.

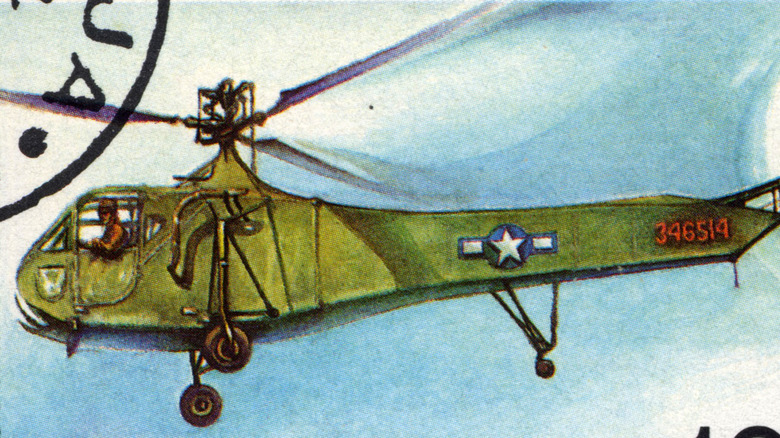

Sikorsky R-4

Some of the earliest first helicopter designs were made in 1908 by Igor Sikorsky, but it would take more than another 30 years before Sikorsky's designs would reach the sky in the form of the Vought-Sikorsky VS-300. But once that made it off the ground, it was just a matter of time before Sikorsky perfected his design into the Sikorsky XR-4.

On April 20, 1942, pilot Les Morris demonstrated the capability of the R-4. SP's Aviation reports that some of the tests included bringing a net bag of raw eggs into the sky and back down to the ground safely, as well as demonstrating how someone can be picked up into the helicopter with a ladder or put down on the ground. By the end of May 1942, the R-4 was part of the United States Army and was first used in American combat two years later in May 1944. The R-4 was used by both the United States and the British forces during the Second World War, making it the first helicopter to be used by either country's military forces. The R-4 is also the first mass-produced helicopter in the world, with 131 made during World War II.

Sikorsky is even considered to be the father of helicopters, even though he didn't invent the concept, because his designs went on to influence helicopters today. According to Engineering & Technology, the single main rotor innovated by Sikorsky is standard for many modern helicopters.

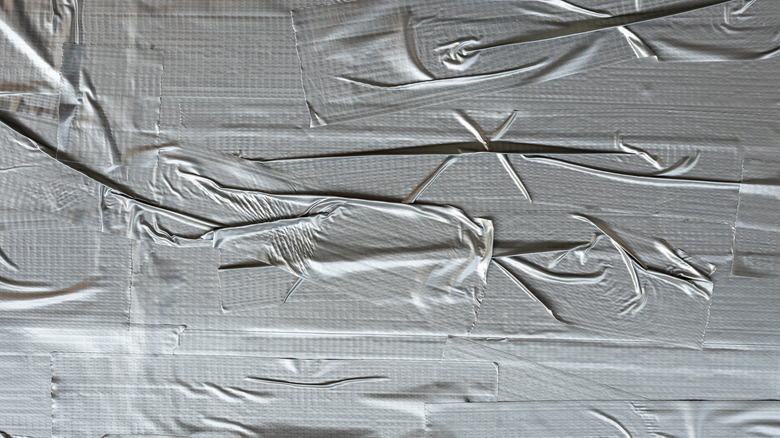

Duct Tape

World War II led to numerous innovations and many military-related innovations, like duct tape, ended up taking on a life of their own after the war. Invented in 1943 by Vesta Stoudt, duct tape was initially made in response to the faulty tape on weapon cartridge boxes. According to ThoughtCo., Stoudt was working at a factory where weapons cartridges were packaged, and she noticed that the boxes had a faulty opening system due to how they were sealed, likely costing precious seconds during battle.

"The Illustrated Histories of Everyday Inventions" records that with two sons of her own serving in the United States Navy, Stoudt felt the need to give U.S. soldiers all the help they could get. Stoudt had the idea to start using waterproof cloth tape to seal the boxes instead, but when she took the idea to her factory supervisors, she was ignored. Undiscouraged, Stoudt took her case to one of the highest authorities in the United States, President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Stoudt wrote a letter to President Roosevelt on February 10, 1943, in which she explained her idea and detailed her innovation. Luckily, President Roosevelt had the good sense to recognize her brilliance, and before long Johnson & Johnson was manufacturing duct tape for the military. Mental Floss writes that the name "duck tape" even came from American soldiers who named it based on how it repelled water "like water off a duck's back." Now, duct tape is used practically everywhere on land and even in space.

Aqua-Lung

Before the 1940s, scuba diving didn't really exist because the word scuba didn't exist. Scuba was originally an acronym that stood for self-contained underwater breathing apparatus and although it was coined by Christian J. Lambertsen for his rebreather, it was French naval officer French engineer Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Emile Gagnan's 1943 invention, the Aqua-Lung, that would go down in history as the original scuba gear.

Cousteau was interested in underwater exploration, but diving bells and diving suits at the time allowed neither flexibility nor mobility. It wouldn't be until he met Gagnan, who had created a new valve for regulating gas flow, that the two of them were able to invent a new valve that allowed for underwater breathing, according to the National Inventors Hall of Fame.

According to "The World's Oceans," edited by Rainer F. Buschmann and Lance Nolde, by 1948, Cousteau was using the Aqua-Lung along with scientists to launch the first underwater archeological expedition as they searched for the wreckage of Mahdia, a Roman ship that sank off the coast of Tunisia around the 1st century B.C.E. By the 1950s, the Aqua-Lung was available for purchase to the U.S. public, and its technology had revolutionized, if not outright created, the scuba industry. Lemelson-MIT writes that the technology of the Aqua-Lung continues to be used as "part of virtually every set of modern SCUBA gear in the world."

Kitty Litter

People kept cats in the house long before the invention of kitty litter. But the predecessor of kitty litter was sand, and cats often tracked silica dust outside of the box. And it took just a single cat owner, Kaye Draper, complaining to Edward Lowe for him to come up with an alternative to sand that would change litter boxes forever.

In 1947, Lowe was working with his father in South Bend, Indiana selling material to heavy industries for soaking up spills. One version of the story is that when Draper asked Lowe if he knew of a litter box alternative, Lowe gave her some clay granules from a sample shipment he'd received. Other versions revolve around frozen sand in the litter box and Draper initially asking for sawdust. But either way, as they say, the rest was history.

Well, not immediately. First Lowe had to convince pet stores and cat owners to try something new. But after making the brand Kitty Litter, Lowe slowly started to build up a clientele. And in 1990, he sold his company for $200 million. By 2017, cat litter was a $2 billion industry.

But according to The Washington Post, the switch from sand to clay may not have been the best decision in the long run. The amount of clay used to make kitty litter is more than all of the waste of Rhode Island. Meanwhile, there's the environmental impact of throwing away used clay-based cat litter, because clay is not biodegradable.

Crash test dummy

It's not that cars didn't get crash-tested before the invention of crash test dummies, but the tests were much more messy and gruesome. Early car crash tests ranged from using the dead bodies of people to the live bodies of pigs. Pigs were especially favored both because of their similar anatomy to humans as well as the ability of scientists to sit pigs upright in the seat.

In 1949, American inventor Samuel W. Alderson created the very first crash test dummy, known as Sierra Sam. However, Sierra Sam wasn't initially used for testing car crashes. Instead, Sierra Sam was used for testing aircraft seats and helmets. But by 1968, the first crash test dummy specifically for automobile accidents was created, according to the American Physical Society. IEEE Spectrum also writes that Sierra Sam eventually had an entire family of crash test dummies, ranging from Sierra Stan and Sierra Susie to little SIerra Sammy and Sierra Toddler. And it's estimated that crash test dummies have saved around 300,000 lives since their invention.

Unfortunately, Sierra Sam perpetuated some of the same issues that were present when using cadavers. When testing with dead bodies and making Sierra Sam, the measurements were always based on an adult cis man's body. According to "Gender Lens Investing" by Joseph Quinlan and Jackie VanderBrug, a crash test dummy modeled off of an adult cis woman wouldn't be built for almost another 40 years after Sierra Sam was first created.

Polaroid instant camera

Smartphones and digital cameras have normalized the idea of seeing a photograph immediately after taking it, but photographs used to come with a waiting time. That is, they did before the Polaroid instant camera came out and revolutionized the photographic experience.

The Polaroid instant camera was developed by Russian-American scientist Edwin Land at Land-Wheelwright Laboratories. Land came up with the idea in 1943 and immediately got to work, though he made sure to keep a tight lid on the project. According to PBS, the original name for the camera was SX-70, "S for secret, X for experimental." And as with most innovations, there's an apocryphal story to go along with it. Supposedly, Land was inspired to create the instant camera after his daughter asked him why she couldn't see a photograph that he'd just taken, writes My Modern Met. By November 1948, the first Polaroid camera was made available to the public in Boston, Massachusetts. And within 20 years, Polaroid sales had sold over $400 million worth of instant cameras.

Although Polaroid saw a slump in its popularity between the 1980s and early 2000s, Polaroid instant cameras have made a comeback in the 21st century, known as Polaroid Originals. Other companies have also since started selling instant cameras, but Polaroid will always be known as the one that got the ball rolling, giving people the chance for the first time to see their memories in real-time.

Color Television

Although designs for color television were proposed a few times in the early 20th century, the first successful innovation towards a color television came from Mexican engineer Guillermo González Camarena in 1940. González Camarena had been experimenting with electricity and television broadcasts from an early age, according to Ciencia Y Desarrollo, per Mexicanist. And by the time he was 23 years old, he registered the very first patent for the color television.

González Camarena patented the "Color Television System Number 1" in 1942 in both Mexico and the United States. And although American universities tried to invest in and develop his idea, The Yucatan Times reports that González Camarena insisted on developing color television in Mexico instead. Although González Camarena tragically died in a car accident in April 1965, his innovations carried his legacy into the depths of our solar system. In 1979, the technology he invented was even used by NASA for the Voyager 1 images of Jupiter.

Although color television wouldn't be made available to the public until the 1950s, and it took some time for the majority of Americans to own a color television, once the floodgates opened there was no going back. By the late-1960s, most of the television networks were working in color, and by the 1990s, the Los Angeles Times reports that black and white televisions accounted for less than 5% of televisions sold.

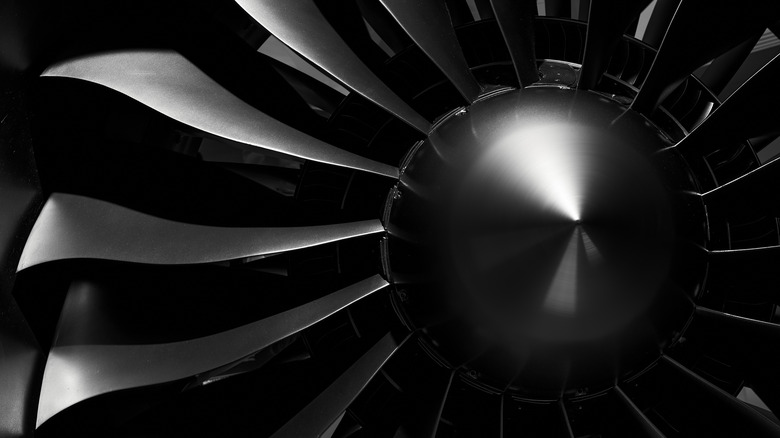

Jet Engine

Although many people throughout history experimented with the idea of jet propulsion and engines, the real breakthrough wouldn't come until the early 20th century. During the 1930s, people like Austrian engineer Anselm Franz, German airplane designer Hans von Ohain, Czech-American airplane designer Vladimir Pavlecka, and English engineer Frank Whittle were all working in their respective countries to create a jet propulsion engine. Von Ohain's jet engine would be the first to take flight in the late 1930s, and Whittle's jet aircraft engine took the first British turbojet into the air on May 15, 1941.

By the 1940s, the outbreak of World War II had underlined the need for jet engine technology. And in early 1944, the Smithsonian Institute writes that mass production began on Franz's Junkers Jumo 004 turbojet engine, which powered the Messerschmitt Me 262, making it the world's "first mass-produced, operational turbojet engine." After the war ended, Interesting Engineering writes that the Allied forces confiscated numerous German planes in order to study their technology.

Since then, jet engines have proliferated in air travel and almost all commercial passenger planes have at least two engines. Jet engines are comparatively safer and cheaper to operate than piston engines, and have made it possible for jumbo jets like the Boeing 747 to fly through the sky.