The Mysterious Life Of Nevada's First Serial Killer, Queho

The two prospectors scrambled up the steep cliff towards the cave's mouth. It was February 1940, and Charles Kenyon and Art Shroeder were scouting for outcroppings that might contain gold. They were on the Nevada side of the Colorado River between the relatively new Hoover Dam — completed just four years earlier — and Eldorado Canyon. The two men first noticed what looked like a purpose-built pile of rocks that someone could hide behind and use as an observation post. Above that lay the cave opening.

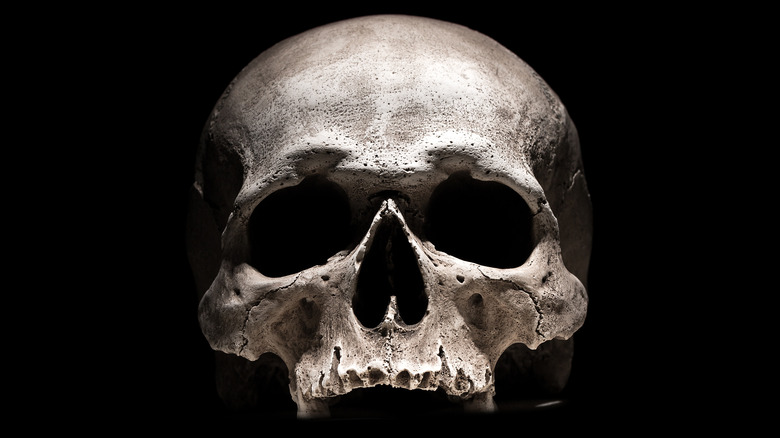

Once inside, the prospectors discovered the mummified remains of what would later be identified as Queho, a notorious bandit and alleged killer. No one had seen the Native American — possibly a member of the Paiute people — for at least a decade. But in his heyday in the early part of the 20th century he'd roamed through Nevada and Arizona, with the press claiming he'd killed at least five people and as many as 23. In death, Queho would cause nearly as much trouble as he did while alive.

His murky past

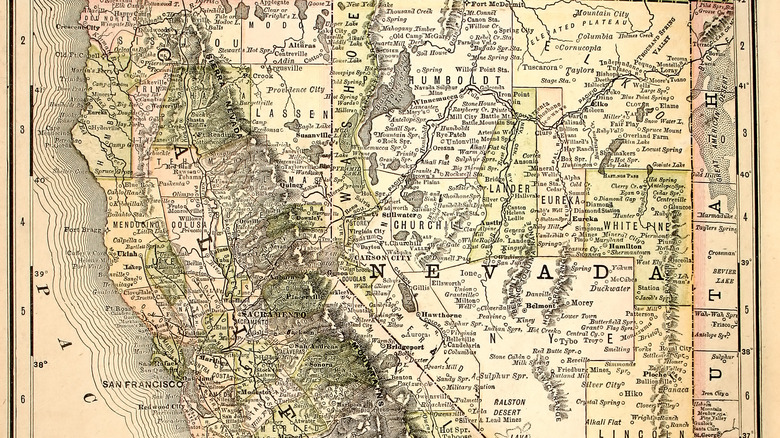

Queho was born around 1880 near Nelson, Nevada, which is now a popular ghost town about 45 minutes south of Las Vegas. His mother, a member of the Cocopah people, died when he was young. There seems to be a lot of conjecture as to who his father was, with the contenders being a white soldier stationed at Fort Mohave, a Mexican prospector, or a member of the Paiute people. Some newspapers called Queho an Apache, but his official designation by the state of Arizona — when the governor offered a reward for his capture — has him listed as a Paiute.

Queho grew up on a reservation in Las Vegas where he was an outcast, possibly because he was mixed-race. He was either born with a clubfoot — a congenital deformity in which the foot is turned inward — or may have suffered a broken foot or leg early in his life. Law enforcement officers would later allege Queho's footprints were easily identifiable because of this.

Queho makes a name for himself

In November 1910, Queho's infamy as an outlaw burst onto the pages of newspapers across the country, from Buffalo, New York to Knoxville, Tennessee. Authorities blamed Queho for the murder of L.W. "Doc" Gilbert, a night watchman at the Gold Bug Mill, across the Colorado River from Nevada in Mohave County, Arizona. The victim was as mysterious as his alleged killer. Doc, it turned out, was an actual physician from California who'd inherited nearly $50 million dollars five years before. No one was sure what he was doing working security at a rural gold mine. After allegedly shooting "Doc" in the back, Queho stole his special deputy badge and fled.

Law enforcement officers also believed Queho was behind a second murder that had taken place not long before. The other victim was a woodcutter with the unlikely name of J.M. Woodworth. Queho had worked for him and felt Woodworth had cheated him out of his rightful pay. Queho's distinctive footprints were at both crime scenes. Lawmen on both sides of the Colorado River began tracking Queho down but with no success. He knew the area too well.

Another series of mysterious murders

In March 1911, Arizona Governor Richard Sloan offered a reward of $500 on top of the $200 offered by Mohave County. Nevada also had a reward for the fugitive's capture, which eventually mounted to $2,000 total, the equivalent of almost $65,000 today. Even with the large reward, no one could capture Queho. He remained on the run and eventually off the front pages of the region's newspapers until 1919.

Someone murdered two prospectors from Utah — William Taylor and E.T. Hancock — and in a separate crime, shot a miner's wife to death in her tent in January 1919 in rural Clark County, Nevada (per The Idaho Statesman). With little evidence besides Queho's telltale tracks in the snow, authorities blamed the murders on him. He had never been captured, much less convicted, in connection to the killings in 1910. Emmet Boyle, the governor of Nevada, called on both Utah and Arizona to help capture Queho and offered another $500 for his capture. Authorities had no better luck this time than they did in 1910 and 1911. There were other alleged sightings and killings blamed on the Native American over the years, but by the 1930s he had seemingly vanished.

The body in the cave

Then Charles Kenyon and Art Shroeder stumbled onto the mummified body in the cave. Besides the man's remains, they found a bow and arrow, a shotgun, and a rifle. They left the body there and went to Las Vegas to alert the police about what they'd found. Las Vegas Police Chief Frank Wait, who had trailed Queho years before, the county coroner, a Las Vegas newspaper reporter named Sherwin "Scoop" Garside, and several of Queho's relatives, made their way to the cave.

As they picked their way up the steep cliff, a member of the coroner's jury, Frank Connors, had had enough. "We don't need any inquest," he remarked, per the Los Angeles Times. "If that Indian climbed this cliff he was so damned tired he just laid down and died." Once inside the cave, there was some dispute about whether it was Queho's body, but the discovery of L.W. "Doc" Gilbert's special deputy badge and a set of keys stolen from the Gold Bug mill helped them positively identify Queho, as did his tell-tale foot. But that was just the beginning of Queho's post-mortem tale.

A fight over Queho's body

The coroner's jury determined Queho had died from "sickness and starvation," according to the Los Angeles Times. Before the authorities removed Queho's desiccated remains, several people took photographs holding up the body at the cave entrance for the newspapers. This was just the first instance of a garish display of insensitivity marked by a bigoted perspective of the time. They deposited Queho's body at a Las Vegas funeral home while they fought over who would get to display it. The Las Vegas Elks Club, backed by the police chief, wanted to feature Queho's body at their Helldorado Museum and had lined up the support of an alleged nephew of the outlaw. The Boulder City Elks also wanted the body. But the county sheriff, who held on to Queho's possessions, found another supposed heir in an attempt to block the Elks from getting the body. Meanwhile, Kenyon, one of the prospectors who found Queho, was hoping to collect the old reward or go to court over the corpse to make money exhibiting it.

In the end, the Las Vegas Elks got Queho's remains and put them on display. A few years later, someone stole the body and related artifacts and scattered the bones in the desert. Roland Wiley, who had been the district attorney of Clark County, Nevada, acquired Queho's body and buried him in Cathedral Canyon near Pahrump, Nevada.